Gender Differences in Clinical Effects of Antidepressant Treatment

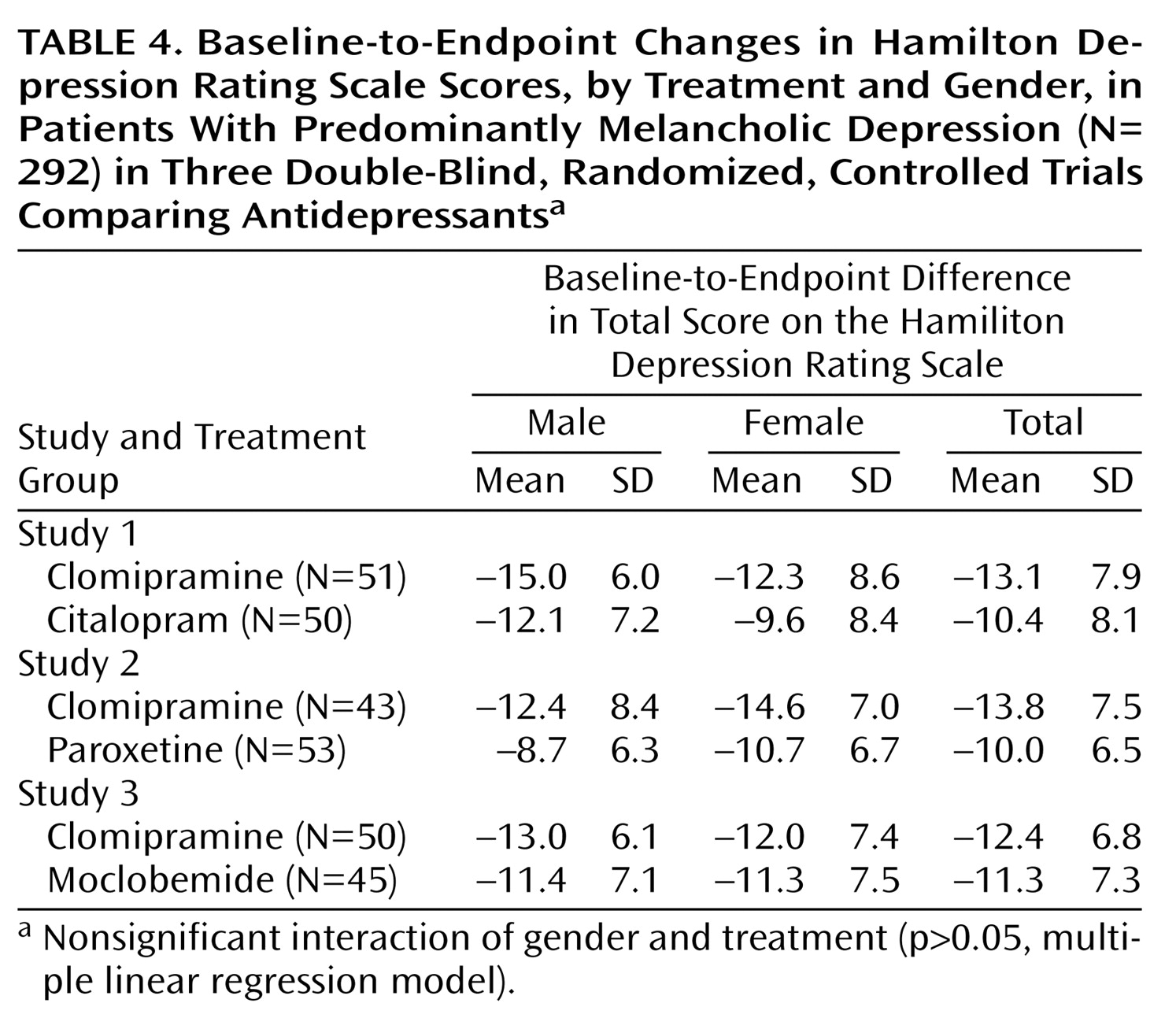

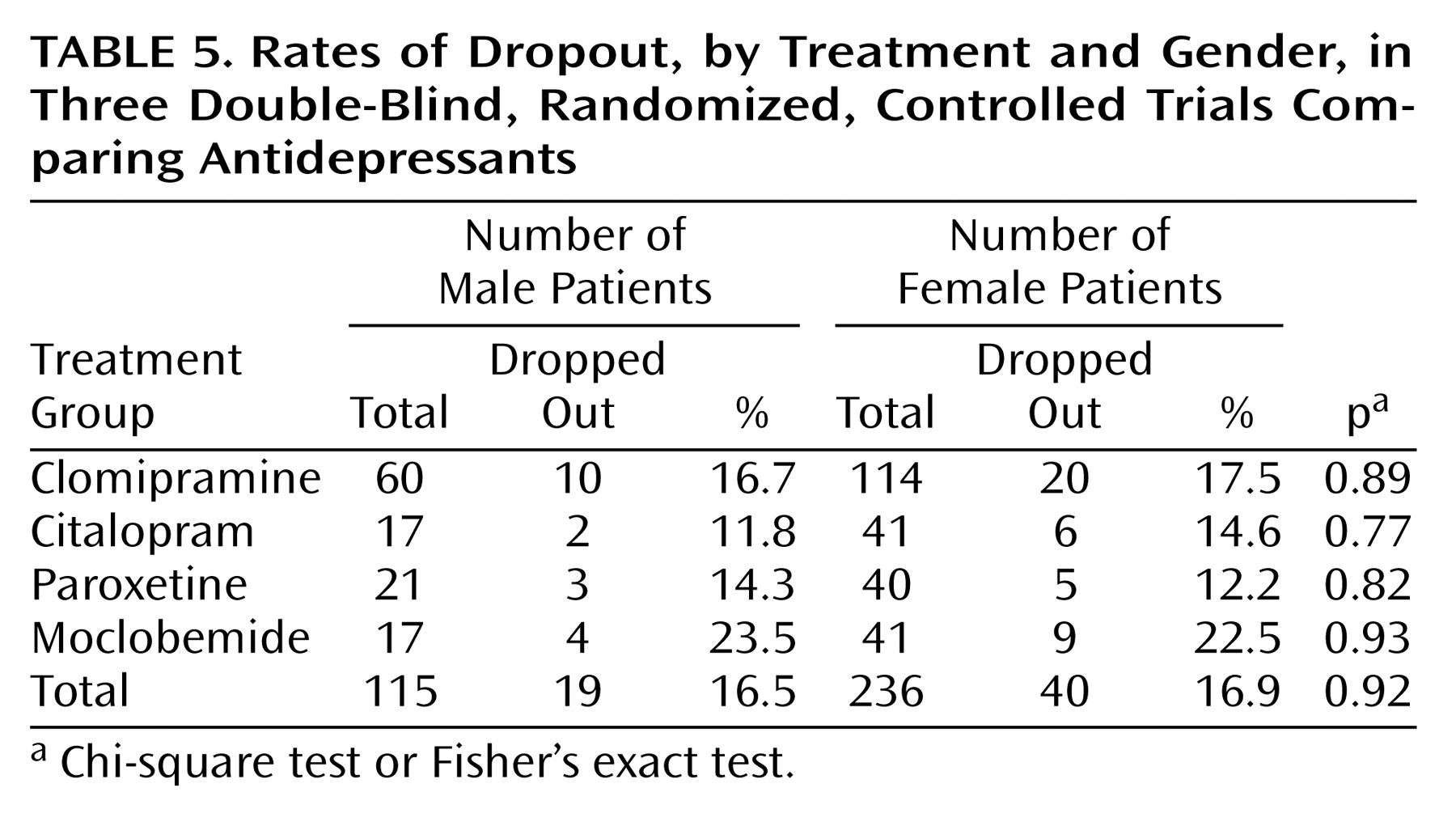

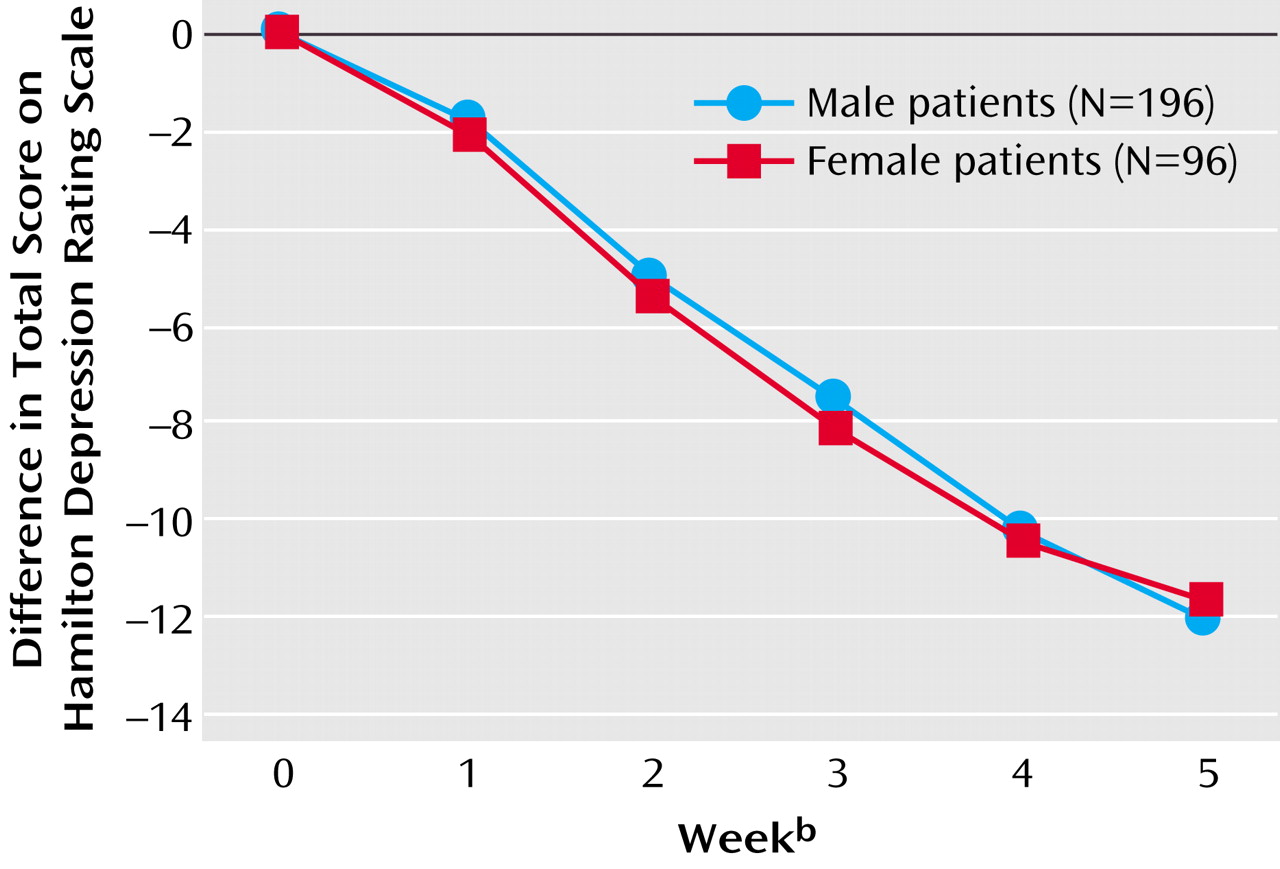

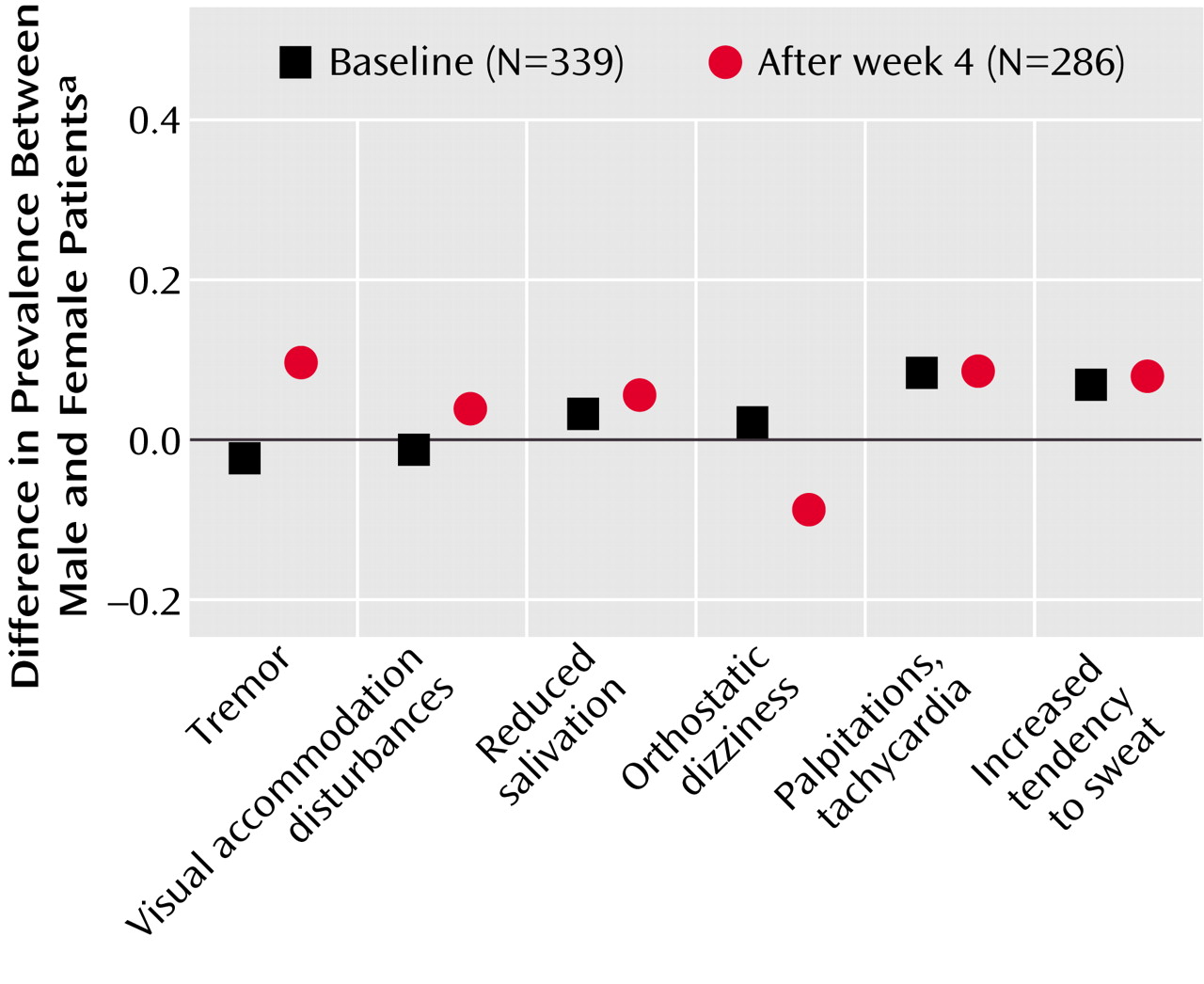

Our analyses showed similar clinical effects of antidepressant treatment for male and female patients with major and predominantly melancholic depression. There were no gender differences with respect to the primary effect measures (Hamilton depression scale difference scores, response and remission rates as measured with the Hamilton depression scale) or secondary effect measures (dropout rates, side effects, and factor analysis).

Other studies have shown a more favorable effect of tricyclic antidepressants for men

(6,

7,

9) and a more favorable effect of SSRIs

(7) and MAOIs

(6) for women.

Kornstein et al.

(7) examined gender differences in treatment response to the SSRI, sertraline (mean dose of 140 mg/day), versus the tricyclic antidepressant, imipramine (mean dose of 200 mg/day). They reported on 635 patients with chronic depression or major depression superimposed on dysthymia. Men had a higher response rate (57%) than women (46%) while taking imipramine, and women had a higher response rate (62%) than men (45%) while taking sertraline. In addition to the gender differences in treatment response, women who were taking imipramine and men who were taking sertraline were more likely to withdraw from the study. One explanation for their findings regarded depressive subtypes. Kornstein et al.

(7) argued that women were more likely to have atypical depressive symptoms

(22), which have been shown to respond preferentially to SSRIs or MAOIs

(23,

24), and that men often have more classic “neurovegetative features” of depression, which are responsive to tricyclic antidepressants

(25,

26).

Davidson and Pelton

(6) reported on 151 patients with atypical depression. They pooled treatment data for phenelzine and isocarboxazid as MAOI treatment and data for imipramine and amitriptyline as tricyclic antidepressant treatment. In a subsample (N=48) of patients with associated panic attacks, they found that MAOIs were superior to tricyclic antidepressants in women and that tricyclic antidepressants were superior to MAOIs in men. The authors

(6) pointed out that the number of subjects in their study was small and that their findings needed further confirmation.

Hamilton et al.

(9) analyzed gender differences in treatment response to imipramine (a tricyclic antidepressant) in a meta-analysis of 180 studies published between 1957 and 1991. Thirty-five studies reported imipramine treatment response rates separately by gender. In 53% of the 35 studies, men showed more benefit from imipramine than women. In 19% of the studies, women received more benefit than men, and in 28% of the studies, no gender difference was observed. They argued that although the meta-analysis of gender and imipramine was comprehensive, it combined studies that used different diagnostic criteria and methods. They suggested that the apparent gender difference in treatment response to imipramine resulted from the inclusion of relatively heterogeneous populations in early clinical trials. They concluded that gender differences in imipramine outcome might have been an artifact of the inclusion of more women with atypical, dysthymic, or anxious depression and of more men with melancholic or endogenous depression

(9).

Quitkin et al.

(8) reported on a large sample of 1,746 outpatients and found no clinically relevant gender differences in treatment response to tricyclic antidepressants, MAOIs, SSRIs, or placebo. Based on the results of studies previously described, they concluded that men might have a slightly better outcome with imipramine, but that it is unclear whether this small advantage is a result of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, or diagnostic differences.

In summary, the studies discussed in this section indicated that the finding of men’s better treatment response to tricyclic antidepressants may be confounded by gender differences in distribution of depressive subtypes in the study samples. There may have been relatively more male patients with the neurovegetative or melancholic subtype of depression and relatively more female patients with the atypical or anxious subtype of depression. These uneven gender distributions of depressive subtypes may have given rise to the findings of gender differences in response to different types of antidepressants.

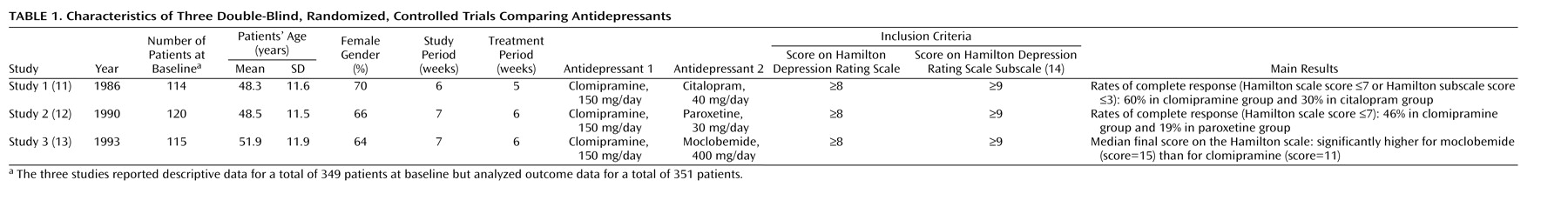

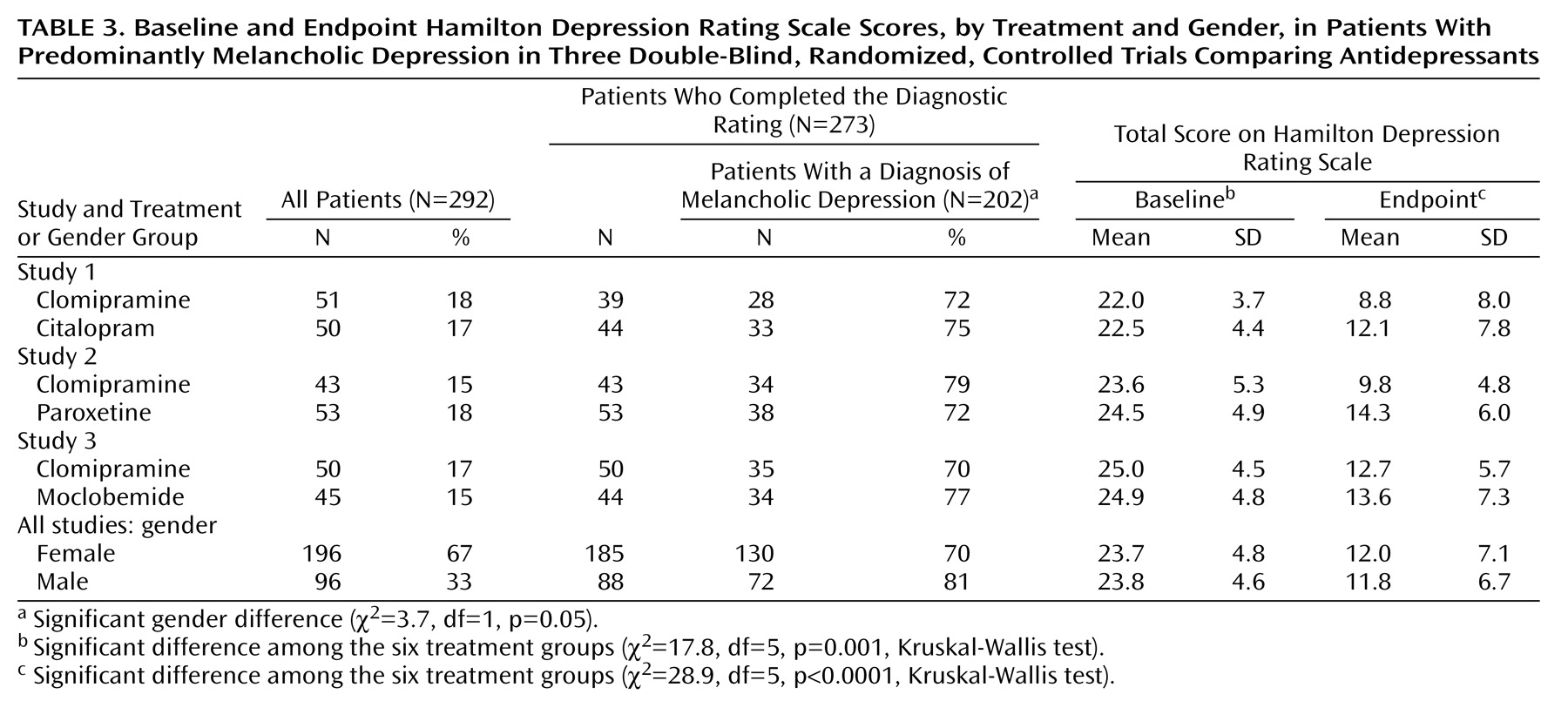

In the present study, we examined a more homogeneous subgroup of hospitalized patients with major and predominantly melancholic depression. Patients were stratified according to melancholic or nonmelancholic depression before being randomly assigned to treatment. A larger proportion of male patients (81%) had melancholic depression, compared with female patients (70%). To avoid the confounding effects of this difference, we adjusted for melancholia in the analyses.

However, this restriction of the subjects to patients with major and predominantly melancholic depression may have been a limitation of this study. Previously we showed that this group of hospitalized patients, who were participating in controlled clinical trials, differed significantly from outpatient subjects in the distribution of melancholic depression

(27). Furthermore, previous findings suggested that in this group with major and predominantly melancholic depression, tricyclic antidepressants seem to be the most effective treatment, more effective than SSRIs

(27,

28).

In the studies used for the present analysis, clomipramine was chosen as the comparison pro-drug because it has the most potent action on 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) of any classic tricyclic antidepressant. Furthermore, it is similar to other types of tricyclic antidepressants

(28).

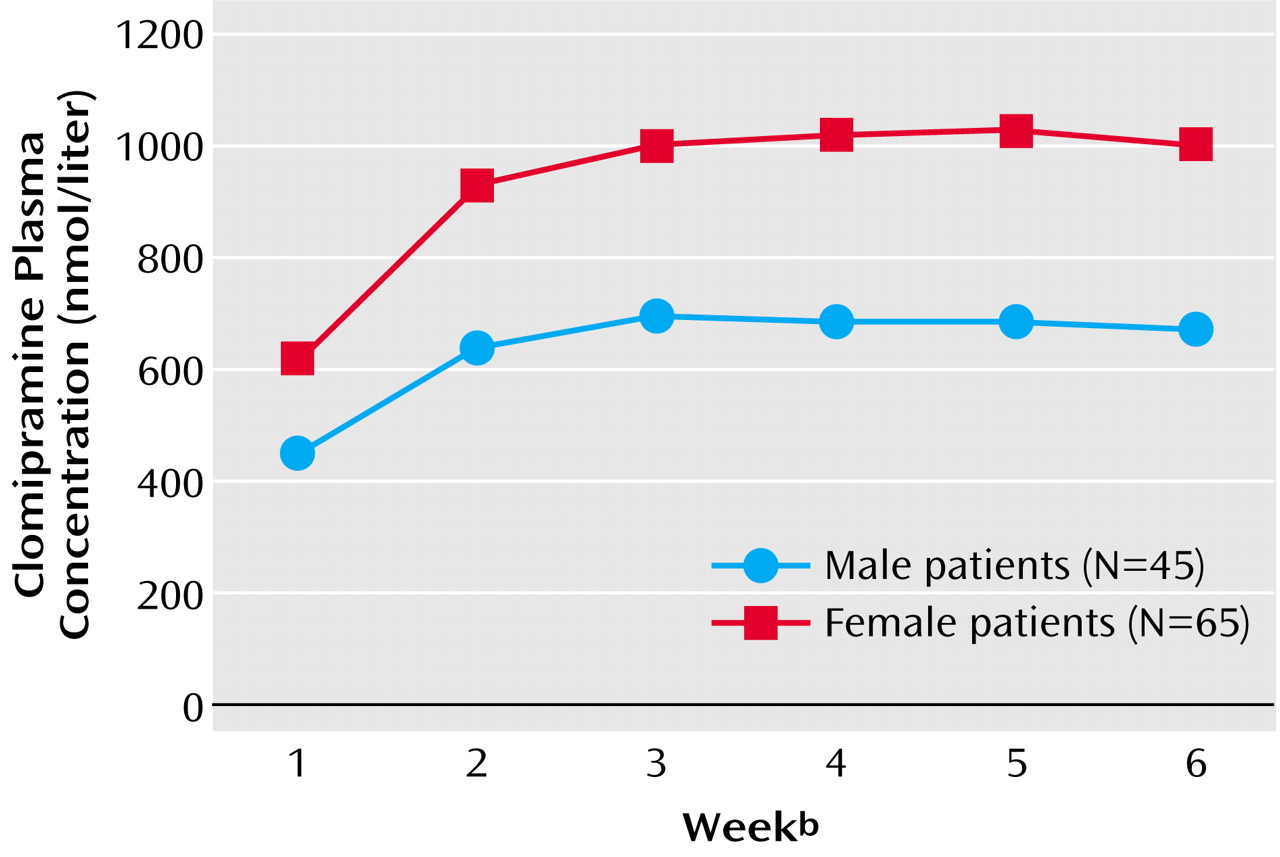

Gender Differences in Plasma Concentrations of Tricyclic Antidepressant

Our analyses showed that female patients had significantly higher clomipramine plasma concentrations than male patients (

Figure 3). However, no relationship between plasma concentration, gender, and therapeutic outcome was found. In concordance with our findings, other studies have reported higher plasma concentrations of tricyclic antidepressants in women than in men

(9,

10).

Hamilton et al.

(9) included in their meta-analysis 12 studies reporting imipramine steady-state plasma concentrations. They found that women had significantly higher dose-adjusted plasma concentrations than men. Since men on average have a higher body weight and thereby a higher volume of distribution, an analysis that controls the effects of weight might find a smaller gender difference in dose-adjusted plasma concentrations. In three of the studies included in the meta-analysis by Hamilton et al.

(9), dose and weight were controlled in determining differences in imipramine plasma concentrations. It appeared that the dose-by-weight adjustment removed the effect of gender in the three studies. However, the authors concluded that there was some support for the hypothesis that clearance of tricyclic antidepressants is slower in women. They suggested that, although data are scant, the use of oral contraceptives and hormonal replacement therapy may further increase the absolute bioavailability of tricyclic antidepressants. Finally, they concluded that little is known about the effects of the menstrual cycle and menopause on the pharmacokinetics of tricyclic antidepressants.

The review article by Frackiewicz et al.

(10) discussed gender differences in depression and in antidepressant pharmacokinetics and adverse events. Based on nine studies reporting higher plasma concentrations of tricyclic antidepressants in women, they concluded that dose adjustment might be necessary for women to ensure a favorable treatment response, compliance, and a low incidence of adverse events. In the present analysis we also found higher plasma concentrations of tricyclic antidepressants in women than in men. However, our results do not entirely suggest that a dose adjustment should be required to ensure the clinical outcomes of treatment with tricyclic antidepressants. Additional studies examining the pharmacokinetics and clinical effects of antidepressants are needed before any conclusions on this topic can be made.

To our knowledge, only one study

(29) has analyzed the pharmacokinetics of clomipramine in relation to gender. In this drug monitoring analysis, the researchers found that women had a significantly lower hydroxylation clearance of clomipramine than men. Potential reasons for our finding in the present study of women’s higher plasma concentrations could be related to time-of-day variance or gender differences in pharmacokinetics influenced by the varying hormonal milieu in women. Medication was given at exact hours, and likewise plasma concentrations were measured at exact hours, so time-of-day variance is quite unlikely. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics influenced by the varying hormonal milieu in women are a considerably more reasonable explanation.

Pharmacokinetics can be divided into the subprocesses of absorption, bioavailability, distribution, and metabolism. There are several sites for potential gender differences within these subprocesses. Absorption of a drug is dependent on its acid-base and lipophilic properties and on the physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. It has been suggested that women may secrete less gastric acid than men, leading to potential gender differences in absorption

(30). A decrease in gastric acid would lead to an increase in absorption of weak bases such as the tricyclic antidepressants. Other sites for potential gender differences in absorption and bioavailability are gastric emptying and gastrointestinal transit time. The gastrointestinal transit time may be prolonged in women during the premenstrual phase

(31). The distribution of a drug is dependent on the drug’s acid-base properties, water and lipid solubility, and affinity for binding proteins. Potential gender differences in blood volume, cardiac output, and percentage of lean body mass could affect the volume of distribution of a drug. The larger blood volume and cardiac output of male subjects and the lower ratio of lean body mass to adipose tissue for female subjects would generally increase the volume of distribution of lipophilic drugs such as the tricyclic antidepressants. The main gender-related metabolic factors that can affect the metabolism of tricyclic antidepressants are first-pass metabolism and the activity of some antidepressant metabolizing enzymes of the cytochrome P450 group. Significant differences according to gender are found for the hydroxylation and elimination of hydroxy metabolites of clomipramine; a lower hydroxylation clearance has been found for female than for male subjects

(29).

The varying hormonal milieu in women may lead to possible menstrual-phase-specific changes that can affect the pharmacokinetics of psychotropic drugs. In addition, the use of oral contraceptives and hormonal replacement therapy may exert an influence on the pharmacokinetics of psychotropic drugs

(9,

32). Unfortunately, data on menstrual cycle, menopausal status, and the use of oral contraceptives and hormonal replacement therapy were not available in the present study. The varying hormonal milieu in women may also lead to gender differences in pharmacodynamics of psychotropic drugs. However, it is unlikely that such differences could account for the higher plasma concentrations of tricyclic antidepressants in women. Female sex hormones have been found to modulate the function of some major neurotransmitters (e.g., γ-aminobutyric acid

A, dopamine, serotonin)

(9), and it is reasonable to expect that the varying hormonal milieu might influence the clinical profile in women. Despite this likelihood, to our knowledge, no publications have addressed gender differences in the pharmacodynamics of psychotropic medication in relation to clinical effects.

In conclusion, to verify that the gender-related pharmacokinetic effects are clinically relevant, it will be necessary to show that they are associated with gender-related differences in therapeutic outcome. In the present study, we found no such relationship with therapeutic outcome. Additional larger studies are needed to examine the pharmacokinetics of antidepressants with dose-by-weight adjustment and to explore the concentration-effect relationship with controls for the effects of hormonal factors in women. In addition, studies examining the pharmacodynamics of antidepressants, with controls for the effects of hormonal factors in women, must produce findings of gender-related differences in clinical profile before conclusions on this topic can be drawn.