Recently, an association of serum cholesterol level with psychiatric disorders, including major depression and anxiety disorders, has been suggested in the literature

(1). Low serum cholesterol has been found to be a risk factor for suicidal behavior in depressive disorder, self-mutilative and homicidal behavior in personality disorders, and even violent behavior during sleep

(2). It has also been suggested that a low serum cholesterol level serves as a biological marker of major depression in panic disorder

(3). Serotonin plays an important role in understanding the underlying neurobiological mechanisms of the relationship of low serum cholesterol concentration with depression, suicide, and violence. In the present study, we examined the levels of serum lipid in patients with dissociative disorders, in which self-injurious behaviors and borderline features are relatively common.

Method

The subjects of the study were 16 patients with dissociative disorder and 16 normal comparison subjects. The subjects were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders

(4) by two psychiatrists (M.Y.A. and H.K.). Their agreement was 95%. Of 16 patients, seven were diagnosed with dissociative amnesia, four with dissociative identity disorder, two with dissociative fugue, and three with dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. The patient and comparison groups were matched for sex, age, and weight. There were 14 women and two men in each group. All comparison subjects were volunteers and were recruited through local announcements about the study. Of 354 subjects who agreed to participate in the study, 16 were matched for sex, age, and weight and met the inclusion criteria. The patients ranged in age from 18 to 36 (mean=25.1, SD=6.7) and in weight from 58 to 83 kg (mean=62.7, SD=18.6). The normal comparison subjects ranged in age from 18 to 37 (mean=25.7, SD=7.2) and in weight from 57 to 85 kg (mean=63.1, SD=19.6). There was no significant difference between the groups in age (t=0.92, df=30, p>0.05) and weight (t=0.89, df=30, p>0.05).

Inclusion criteria for the study were 1) meeting the DSM-IV criteria for dissociative disorder (for patients), 2) age between 18 and 65 years, 3) good physical health as determined by physical and laboratory examinations, and 4) no history of psychotic disorders or current substance abuse. None of the patients was treated with antidepressants or benzodiazepines during the study. No patients were in the hospital for long periods where their diet would have been different. There was a washout period (at least 2 weeks) of taking psychotropic drug before blood was collected. The comparison subjects were also drug free during the study.

Written informed consent was obtained after the procedures had been fully explained to the subjects, and all of them gave informed consent to participate in this study and were requested to avoid medication affecting lipid levels (e.g., beta-blockers, diuretics, androgens, estrogens, disulfiram, corticosteroids, levodopa, and aminosalicylic acid) for at least 2 weeks. All subjects were also free of cholesterol-lowering diets and medications. There was no potential difference in diet between the groups. Blood samples were drawn after a night of fasting. Venipuncture was conducted in a sitting position with a tourniquet. Blood was then centrifuged at 940 g for 1 minute in a refrigerated centrifuge, and the serum samples were separated from the cells. Cholesterol, triglyceride, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were determined in the serum by commercially available kits (Roche Diagnostic GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) on a Hitachi 747 auto analyzer (Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo). An enzymatic colorimetric method was used for cholesterol and triglyceride determination. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol was measured by using the direct high-density lipoprotein method. Low-density lipoprotein and very low density lipoprotein cholesterol were calculated according to the formula of Friedewald et al.

(5).

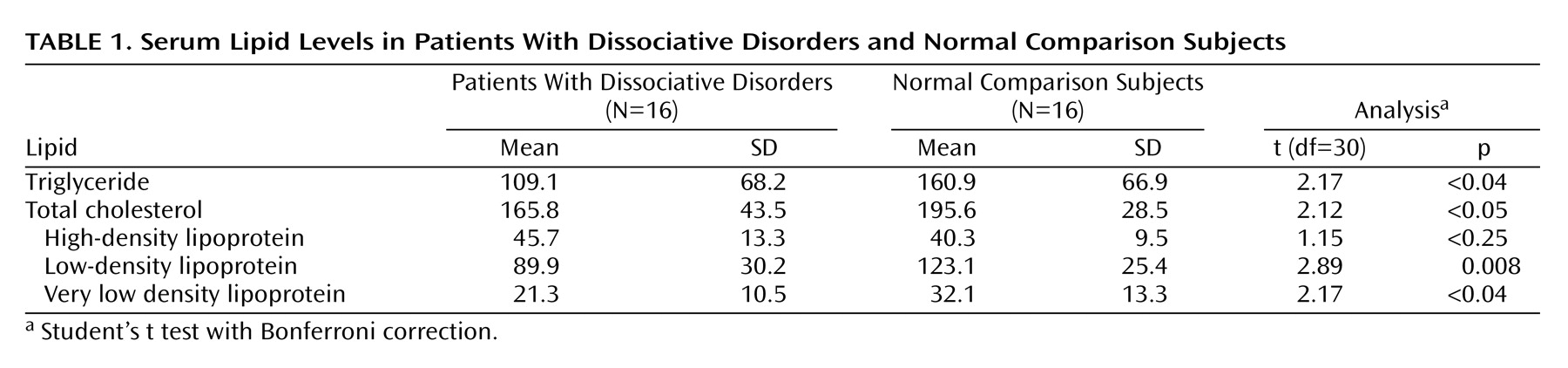

All data are reported as the mean and one standard deviation. Group data were analyzed by using Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction. Analysis was performed with SPSS for Windows, version 9.01 (SPSS, Chicago).

Discussion

In this study, we found that patients with dissociative disorders had lower serum triglyceride, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, and very low density lipoprotein levels than normal comparison subjects. When we compared the patient lipid values to standard clinical reference values

(6), they were quite low. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine serum lipid levels in patients with dissociative disorders, although it has been performed in a small group.

Serotonin has recently been attributed to an important role in the relationship between low cholesterol level and suicidal or aggressive behavior

(1). Reduced CSF concentration of hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), the principal metabolite of serotonin, in depressed patients suggests that a low concentration of 5-HIAA may be a marker for suicidal behavior and suicide risk in depressed patients

(7). Peripheral cholesterol exchanges freely with that in the CNS, which suggests that as a principal component of neuronal membranes, the concentration of cholesterol could determine the availability of the serotonin receptor and its transporter by inducing changes in their quaternary structure

(8). Investigating the relation of serum cholesterol and serotonin metabolism, Steegmans et al.

(9) reported that plasma serotonin concentrations were lower in men with low serum cholesterol and suggested that serotonin metabolism might be involved in the association of cholesterol and serotonin. Thus, low levels of total serum cholesterol lead to a decrease in brain serotonin and, as a consequence, to poor control of aggressive impulses and suicidal or violent behaviors

(1).

Dysphoria is a hallmark of borderline personality disorder, which is often associated with the initiation of self-mutilating and suicidal behaviors

(10). Comorbidity with borderline personality disorder or borderline features is high in patients with dissociative disorders, particularly dissociative identity disorder. In addition, Coons and Milstein

(11) reported a high incidence of self-injurious behaviors among patients suffering from multiple personality disorder, psychogenic amnesia, and dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. An association between low serum cholesterol and borderline personality disorder

(12), impulsivity

(13), and self-mutilation

(14) have been reported in recent studies. Thus, low serum lipid levels may be related to a high incidence of self-injurious behaviors and borderline features in patients with dissociative disorders. In conclusion, future research is needed to replicate these findings and to demonstrate a causal relationship between low cholesterol concentration and serotonin in dissociative disorders as well as in major depression and borderline personality disorder.