Free-floating generalized anxiety was a prominent feature in Freud’s psychoanalytic theories and the central feature of his “anxiety neurosis”

(1). DSM-I, the foundation of which was largely based on psychoanalytic thinking, characterized anxiety as the “hallmark” of neurotic disorders. Generalized anxiety disorder first made its appearance as a syndrome separate from panic disorder in the Research Diagnostic Criteria

(2) as a refinement of the earlier concept of “anxiety neurosis” and was subsequently included in DSM-III. Research into generalized anxiety disorder as a distinct entity suggested revisions in the diagnostic criteria that were incorporated into DSM-III-R and DSM-IV, which have improved the nosological status of generalized anxiety disorder. However, its diagnosis remains controversial since some authors contend that generalized anxiety disorder may not represent an autonomous syndrome but rather a nonspecific cluster of “residual” anxiety symptoms stemming from other disorders

(3), although others believe it is better characterized as an anxious temperament type

(4) or a vulnerability to developing other anxiety or mood disorders

(5).

Neuroticism, on the other hand, has enjoyed a well-accepted role in the characterization of personality traits. Reflecting a tendency toward states of negative affect

(6), it, together with extroversion and psychoticism, constituted the three key dimensions of personality, according to Eysenck and Eysenck

(7), and has been included in nearly all theories of personality since its introduction. It possesses good psychometric properties of item and construct validity, stability, and cross-cultural validation. Gray and McNaughton

(8) contended that anxiety proneness is primarily captured by measures of neuroticism, together with smaller contributions from the dimension of extraversion.

Generalized anxiety disorder and neuroticism have considerable overlap in their descriptive features. Generalized anxiety disorder is a clinical disorder characterized by excessive, chronic worry regarding multiple areas of life as the central feature distinguishing it from other anxiety and mood disorders. DSM-IV requires at least three of six associated symptoms of restlessness, fatigue, concentration difficulty, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance for a minimal duration of 6 months, while DSM-III-R also included other somatic symptoms related to motor tension or autonomic hyperactivity. Also required is a hierarchical diagnostic exclusion from mood, psychotic, and pervasive developmental disorders, exclusion of an “organic” etiology (substance use or a medical condition), and the occurrence of clinically significant distress or impairment because of the anxiety (DSM-IV only). Neuroticism, as assessed with the short form of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire

(9), contains 12 items that overlap with some of the diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, such as irritability, nervousness, worrying, and feeling tense. A total score (range=0–12) is obtained by adding the number of items endorsed by the subject. It does not have duration or impairment requirements.

What is the relationship between generalized anxiety disorder and neuroticism? High levels of neuroticism have been observed in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders. Most studies find higher than average neuroticism in women than men, and the lifetime prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder in women is about twice that of men. Twin and family studies of generalized anxiety disorder have found significant familial aggregation that is largely accounted for by genetic factors of moderate effect

(10), while several twin studies have estimated the heritability of neuroticism ranging from 0.3 to 0.6, with little or no role for the family environment

(11–

13). One large population-based twin study that examined neuroticism and self-report symptoms of anxiety and depression

(14) concluded that genetic variation in these symptoms is largely dependent on the same factors as those that affect neuroticism.

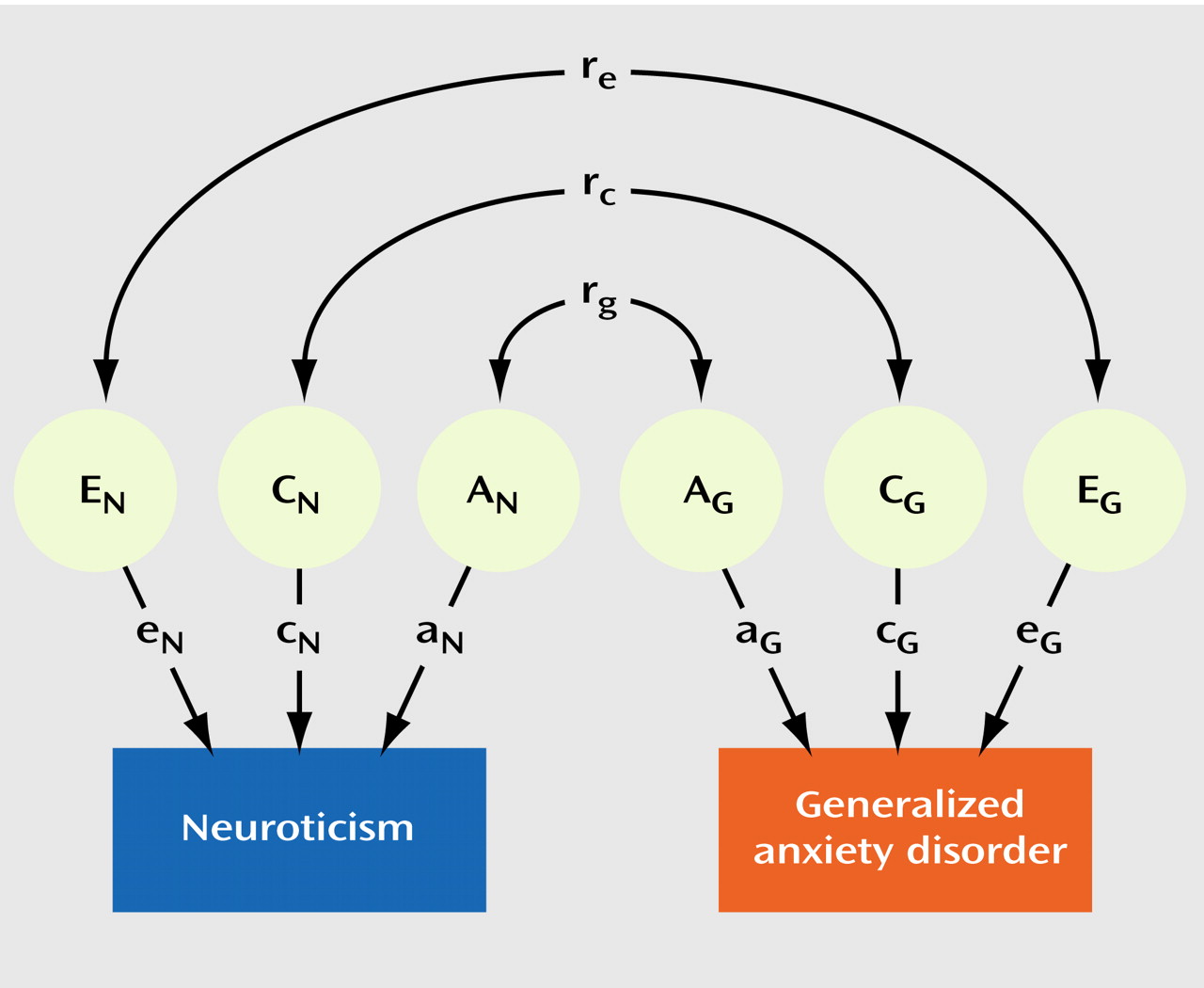

In this study, we sought to determine the sources of individual covariation between the semiquantitative personality trait of neuroticism and the psychiatric illness of generalized anxiety disorder. Specifically, we examined to what extent neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder share the same genetic risk factors, environmental risk factors, or both. In addition, we explored the potential sources of sex differences in these shared risk factors.

Results

In our sample, the mean neuroticism score for women (3.289) was significantly higher than for men (3.046) (pooled t statistic=3.34, df=7206, p=0.0009). The 12 items from the short form of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire that make up the total score exhibited good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.84). The reliability of our broad, 1-month generalized anxiety disorder diagnosis was quite low (kappa=0.34) but comparable to the 6-month DSM-based definition (kappa=0.25).

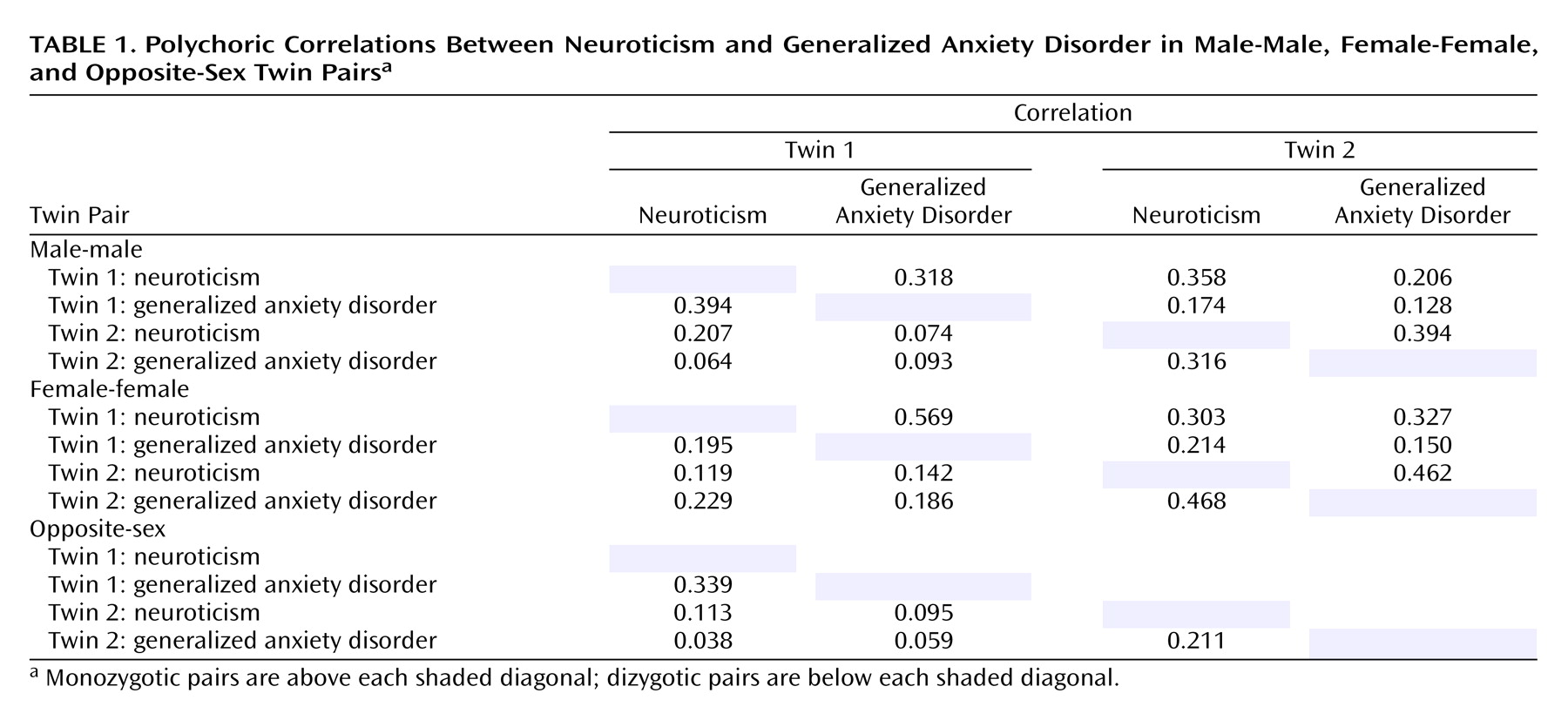

Table 1 depicts the polychoric correlation matrices for neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder in male and female same-sex monozygotic and same- and opposite-sex dizygotic twins. Monozygotic correlations are listed above and dizygotic below each shaded diagonal, respectively. There was substantial within-twin correlation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder (0.2–0.4), corresponding to the often-observed covariation of neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder within subjects. A higher overall monozygotic than dizygotic cross-twin correlation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder suggested that genetic factors play a role in their covariation, just as higher monozygotic than dizygotic resemblance for a single trait occurs because monozygotic twins share 100% of their genes in common compared to only an average 50% for dizygotic twins. Also, this effect appears slightly larger in men, indicating that the genes accounting for the covariation of neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder may have a greater impact on men. In addition, smaller cross-twin dizygotic correlations between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder and between the opposite sex and the same sex suggest a possible role for sex-specific factors.

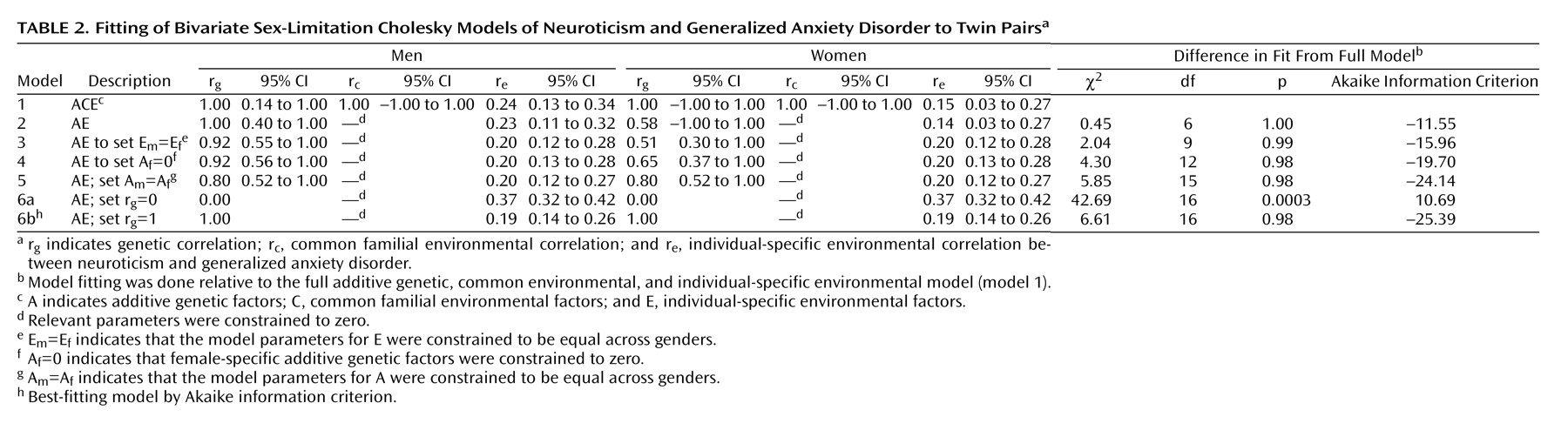

Table 2 illustrates the results of our model-fitting procedure. The full model (model 1) included additive genetic, common environmental, and individual-specific environmental sources of variance and covariance for neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder, with both male-female shared and sex-specific genetic factors. Estimates for r

g, r

c, and r

e were 1.00, 1.00, and 0.24 for the men and 1.00, 1.00, and 0.15 for the women, respectively, with wide confidence intervals. Model 2 constrained the common environmental sources of variance to zero since these are estimated to be zero or almost zero for both neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder in both sexes, as had been observed in univariate analyses for these variables previously. This model was essentially identical in goodness of fit but with a lower (i.e., more negative) Akaike information criterion. This also produced nearly the same estimates for the correlations except for a reduction in the female genetic correlation (0.58) and a smaller confidence interval for the male genetic correlation. We constrained the magnitude of the individual specific environment to be equal across genders in model 3 without significant difference in model fit, as suggested by the similarity of their point estimates. This produced minor fluctuations in the point estimates of the correlations. Model 4 tested the significance of evidence for sex-specific genes by setting their path loadings to zero. This resulted in a nonsignificant deterioration in fit and a more negative Akaike information criterion compared to model 3 and was, thus, more preferable. Model 5 then tested whether the magnitude of the additive genetic sources of covariation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder differed between men and women by constraining male and female model parameters to be equal, again resulting in a model with a more negative Akaike information criterion. Models 6a and 6b tested the alternative hypotheses that neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder share none (r

g=0) or all (r

g=1) of their genes in common. Model 6a had a significantly poorer fit to the data compared to model 5 (Δχ

2=36.84, df=1, p<0.0001), while model 6b fit the data almost as well as model 5 but with slightly more negative Akaike information criterion, making it the overall best-fitting model by that criterion.

Discussion

This study used bivariate modeling of twin data to examine the genetic and environmental risk factors shared by the personality trait of neuroticism and the psychiatric illness generalized anxiety disorder. Our results suggest that the genetic factors underlying neuroticism are nearly indistinguishable from those that influence liability to generalized anxiety disorder. Environmental risk factors, on the other hand, are only modestly correlated between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder. By applying the sex-limitation structure to these models in both same-sex and opposite-sex twin pairs, we attempted to determine whether this was dependent on gender. While the genetic correlation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder was estimated to be (nonsignificantly) smaller in women than in men, our findings apply equally to men and women.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the factors underlying the relationship between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder. Previous analyses have examined the effects of genes and the environment for neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder separately. The most detailed findings for neuroticism came from two large-scale twin/family studies. They reported both additive and nonadditive genetic factors for neuroticism, no significant contribution from shared environment, and sex differences in the magnitude but not the source of genetic effects (i.e., the same genes are expressed differently in men and women). Our sample did not possess the statistical power to significantly detect nonadditive genetic factors or sex differences, although the latter were suggested. In a prior analysis in our sample, we did not detect gender differences in genetic or environmental factors for generalized anxiety disorder

(20). A large, population-based study of Australian twins that examined the covariation between neuroticism and current depression and anxiety symptom scores reported genetic correlations between neuroticism and anxiety scores of about 0.8 in both sexes

(14).

Our group had previously performed a similar analysis of neuroticism and major depressive disorder in this sample

(24). In that study, the within-sex genetic correlations between neuroticism and major depression were estimated at 0.68 for men and 0.49 for women, with this model fitting only slightly better than one with a correlation between neuroticism and major depression of 0.55 for both sexes. In addition, the correlations between neuroticism and major depression were significantly different from 1.00. This suggests that although major depression and generalized anxiety disorder have a genetic correlation near unity

(25), some differences in their correlation with neuroticism may exist. This is not inconsistent since a study that uses a semiquantitative variable such as neuroticism has greater statistical power to detect differences than one that uses only dichotomous variables such as major depression and generalized anxiety disorder

(19).

There are several potentially important implications of our findings. First, neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder share a significant proportion of their liability genes in common but only a modest proportion of individual environmental risk factors. Such a high correlation with the genes for neuroticism may have implications regarding generalized anxiety disorder’s place in psychiatric nosology. Is generalized anxiety disorder better characterized as an anxious personality type that belongs on axis II, as some have speculated

(4), or rather, is generalized anxiety disorder an axis I syndrome that develops from the same liability genes as those for neuroticism but with different predisposing life events? Given the shorter, modified duration criteria for generalized anxiety disorder used in these analyses and the design of this study, we are unable to adequately address the hypotheses herein. Second, our findings of the same or a higher genetic correlation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder in men do not support the hypothesis that the relationship between higher levels of neuroticism and rates of generalized anxiety disorder in women may be explained by a greater sharing of genetic risk factors in women. Finally, several groups have proposed using neuroticism as a quantitative intermediate or “endo” phenotype in molecular genetic investigations of depressive and anxiety disorders

(26) based upon either phenotypic studies of the overlap between levels of neuroticism and these disorders or twin study findings of high genetic correlation between neuroticism and symptom scores. While this study was not designed to test the endophenotypic hypothesis directly, our findings suggest that neuroticism may serve as a useful target in identifying liability genes for generalized anxiety disorder. This has increasing relevance because both association

(27) and linkage studies

(28) have identified putative genetic regions that influence individual variation in neuroticism.

The results of this analysis should be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. First, we used a broadened DSM-IV definition of generalized anxiety disorder with a 1-month minimum duration in order to increase the prevalence and maximize our power to estimate model parameters. Although we have previously shown that this modification does not substantively change genetic modeling for generalized anxiety disorder as long as the diagnostic hierarchy with major depression is preserved

(20), we felt it prudent to examine the effects of these changes on the present analyses. Neither increasing the minimal duration to the usual 6 months nor using the narrow DSM-IV criteria produced significantly different results from those presented here. Estimates for r

g and r

e varied somewhat from one analysis to another because of the lower statistical power, but the overall findings remained the same. The same was true when DSM-III-R-associated symptom criteria were substituted for those from DSM-IV. Thus, our findings do not strongly depend upon the definition we chose to use in our analyses.

Second, although the genetic correlation between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder may be higher in men than women, our sample did not possess the statistical power to confirm this. Thus, despite the size of our sample, we were limited in our ability to detect sex differences in the factors underlying the covariation of neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder. The finding of gender differences in the genetic correlation, if replicated, may have important implications for identifying genes for generalized anxiety disorder in the two sexes when using neuroticism as an endophenotype.

Third, the findings of this analysis are predicated on the assumptions of the method used, that is, the structural equation modeling of twins. These assumptions include the independence and additivity of the latent variables, the absence of assortative mating, and equal correlation in monozygotic and dizygotic twins for environmental experiences of relevance to the trait under study

(21). If the latter, known as the equal environment assumption, is violated, higher monozygotic similarity could potentially result from increased monozygotic environmental similarity instead of higher genetic similarity. While we have not detected such violations for generalized anxiety disorder in this sample

(20), this cannot be ruled out for neuroticism. Differences in heritability estimates of neuroticism from twin and adoption studies have in the past been attributed to either violations of the equal environment assumption or nonadditive genetic effects

(29), with the latter seeming more likely, given their unambiguous detection in the large twin/family studies cited.

Fourth, neuroticism and lifetime history of generalized anxiety disorder were assessed at one time point, which potentially confounds the effects of individual-specific environment and measurement error, reducing the corresponding estimates of genetic effects. For example, we have found, for major depression in our female-female sample, that improving the diagnostic reliability by reducing error by means of multiple sequential assessments increased the heritability estimate substantially

(30). This measurement “noise” may also have the effect of reducing the correlations between neuroticism and generalized anxiety disorder—in particular, the individual-specific environmental correlation, r

e. Given the low reliability we found for generalized anxiety disorder, this may have a substantial effect on our results. If this is the case, our analysis may have underestimated r

e.

Fifth, because the sample was made up entirely of Caucasians, these results may not generalize to other ethnic groups.