Diagnostic overlap is partly rooted in research methodological practices, such as the propensity of most investigators to single out a particular diagnosis for special study rather than adopting a comprehensive view that facilitates detection of overlap. Furthermore, the empirical foundation of the somatoform diagnoses is poor, as it emanates mainly from a clinical tradition based on observation of patients in severely skewed psychiatric settings, despite the fact that these patients are mainly encountered in general medical settings.

The main focus of this study was the diagnosis of hypochondriasis, the principal diagnostic criteria for which are, according to DSM-IV, a nondelusional preoccupation with fears of harboring a severe physical disease (criterion A), persistence of the preoccupation despite appropriate medical evaluation and reassurance (criterion B), clinically significant distress or interference with functioning (criterion D), and a duration of symptoms of at least 6 months (criterion E)

(19, ICD-10). Criteria B and D also apply to several other somatoform disorder diagnoses, and criterion A is frequently seen in patients with other somatoform disorders, implying an overlap problem. Furthermore, Gureje et al.

(17) showed that nearly no patients in primary care fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for hypochondriasis and that the major cause for this was criterion B, i.e., it is unusual for patients not to respond to reassurance at all despite appropriate medical evaluation. Criterion E is also problematic because the time limit is arbitrary and it limits the value of the diagnosis in nonpsychiatric settings, particularly primary care, where most patients whose illness lasts more than 6 months are viewed as having chronic disorders

(16). Moreover, it is hardly possible to study the effect of early intervention when by definition a diagnosis cannot be made at an early stage. Thus, the current DSM-IV hypochondriasis diagnosis satisfies neither clinical nor nosological diagnostic validity requirements.

The present situation therefore leaves us with an urgent need for empirical nosological studies on hypochondriasis. The studies must draw on appropriate patient populations, state-of-the-art assessment methods, and advanced statistical aids. Such studies should seek both to validate the current hypochondriasis diagnosis and to systematically examine whether inclusion of other symptoms known to be associated with hypochondriasis improves the validity of the diagnostic criteria.

In the present study we aimed to fill this gap by investigating whether a select range of candidate symptoms for a new hypochondriasis diagnosis cluster in certain individuals and by proposing a distinct and discrete nosological disorder entity separable from other somatoform and psychiatric disorders.

Method

The study group included 1,785 consecutive patients of Scandinavian origin (ages 18–65 years) who consulted their primary care physicians during a 3-week period for new medical problems. All participants were covered by the National Health Care Program, which includes 98% of the Danish population; each individual is registered with one primary care physician. A patient can consult only the primary care physician with whom he or she is listed. With a few exceptions, e.g., emergency cases, almost all specialized treatment, including hospital admission, requires referral from the primary care physician.

The Danish Health Care System is almost entirely tax financed, and with a few exceptions, all medical care is free of charge.

The study was a part of a large randomized, controlled trial on the effect of educating primary care physicians about the treatment of somatizing patients and the effect of diagnostic aids. All 430 primary care physicians from the 271 practices in the county of Aarhus were invited to participate in the study, and 38 agreed. There were no statistical differences between the included primary care physicians and those who declined the invitation to participate as to type of practice, length of postgraduate psychiatric training, age, or gender. However, the participating primary care physicians had less experience (mean=10.3 years, SD=7.2) than the nonparticipants (mean=14.1 years, SD=8.5) (likelihood ratio test: χ2=9.0, df=1, p=0.005), and more of them had participated in extended (more than 3 days) courses in communication skills and psychological therapy: 52.8% (19 of 36) versus 39.6% (113 of 285) (likelihood ratio test: χ2=4.0, df=1, p=0.05).

The predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were met by 2,197 patients, of whom 274 declined the invitation to participate and 138 did not participate for other reasons (forgot their glasses, the secretary was too busy, etc.), leaving 1,785 patients for analysis. The mean age of those declining participation was 42.2 years (SD=13.1) compared with 38.8 (SD=12.9) among the included participants (t=–4.0, df=2046, p<0.001). There was no significant gender difference between the two groups. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained.

Study Design and Procedures

A two-phase design was used. First, a screening questionnaire was distributed to all patients in the waiting room. This questionnaire included, among other things, the eight-item version of the Symptom Check List (SCL)

(20,

21) assessing anxiety and depression; the seven-item Whiteley index

(22), which measures worrying and convictions about illness and somatoform disorders; the somatization subscale of the SCL, which checks for 12 common physical symptoms

(23); and the CAGE, which consists of four questions screening for alcohol abuse

(24).

After the consultation, the primary care physician filled in a questionnaire on the assessment results and his or her judgment of the patient.

Selection of Patients for Psychiatric Diagnostic Interview

The responses to each item were dichotomized. Patients with a total score of 2 or more on the eight-item SCL, the seven-item Whiteley index, or the CAGE or a score of 4 or more on the SCL somatization subscale were selected for the second phase—a psychiatric diagnostic interview. Furthermore, a random sample of one-ninth of the remaining patients was selected for interviews to produce a stratified subsample consisting of all patients with high scores and one-ninth of those with low scores. The cutoff values were chosen on the basis of a sample size calculation and the performance of the screening scales in a previous study in primary care

(20,

25). The aim was to include 400 patients with somatoform disorders in the study while performing no more than 800 psychiatric interviews, which was the maximum capacity of the psychiatric interviewers. We selected 894 patients for interview, but 193 (21.6%) declined the invitation, leaving 701 patients for interview. A comparison of those declining the interview with those who completed the interview (

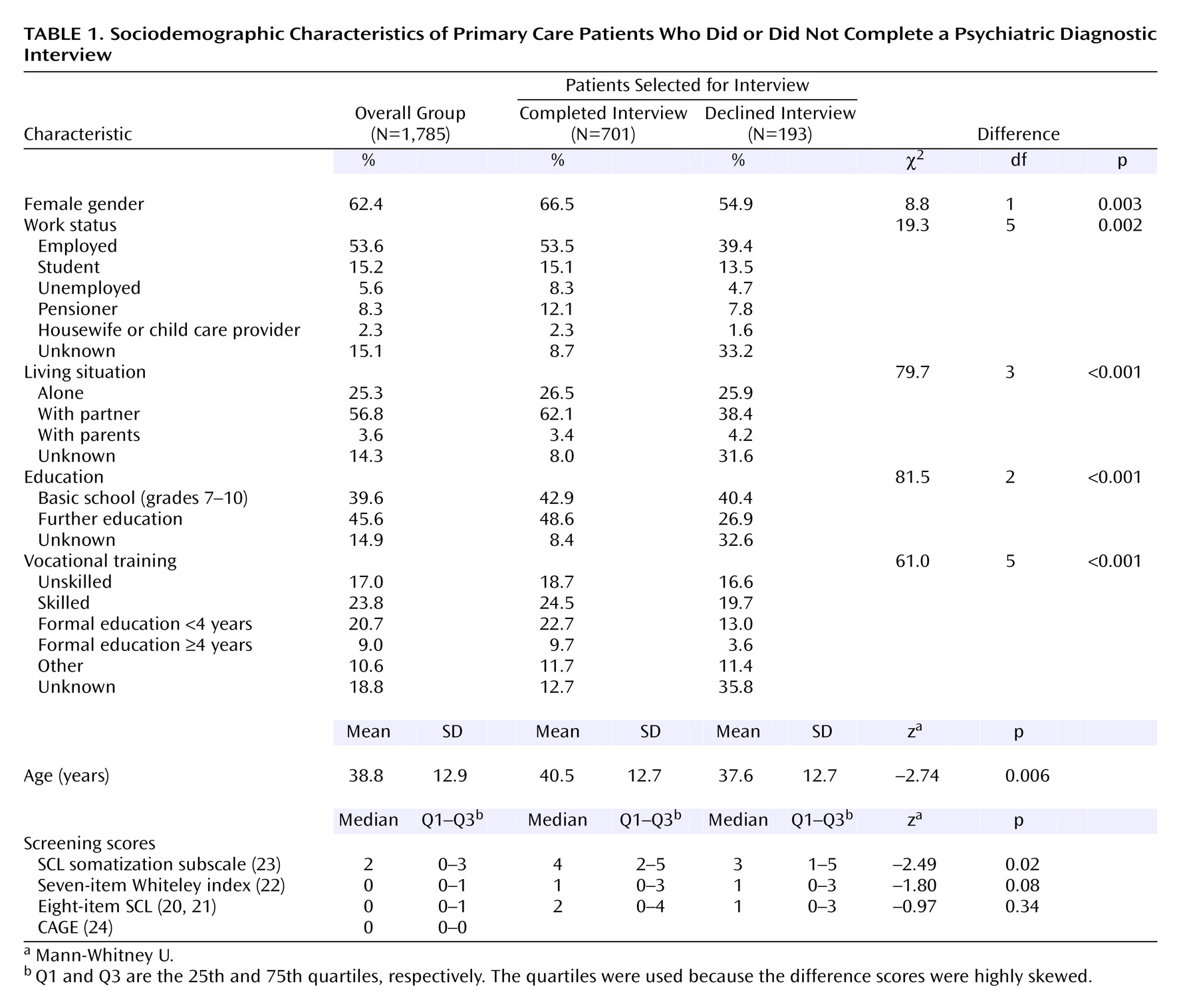

Table 1) shows that the former group contained a higher proportion of men, was younger, and had more missing answers to the questions about sociodemographic variables. Fewer patients in the group declining interview were employed or living with a partner, and fewer had an education beyond basic schooling. They had lower scores on the SCL somatization subscale than did the patients who completed interviews (2003 unpublished study by T. Toft et al.).

Psychiatric Research Interview

The psychiatric interview was conducted as soon as possible after the index contact, in the primary care physician’s office, in the research unit’s office, or in the patient’s own home. The patients’ transportation expenses were reimbursed. For patients who could not be interviewed immediately, the interview did not include the period after the index contact.

The psychiatric interviews were made by means of the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN), version 2.1

(26,

27), which is a standardized comprehensive interview endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) that covers all types of mental disorders. It is a semistructured interview, and its use requires an interviewer who has received psychiatric training. The interview lasts between 30 minutes, in cases of no health problems, and several hours, in cases of more massive psychopathology (the maximum in this study was 7 hours). In this study the interviewers were free to explore aspects they did not find fully clarified by the interview, e.g., by reviewing medical records. However, they were not allowed to contact the primary care physicians.

In the literature a range of cognitive and emotional symptoms, beside those specified in DSM-IV (and ICD-10), are commonly reported in patients with hypochondriasis

(19,

28–30):

1.

Worrying about or preoccupation with fears of harboring a severe physical disease (DSM-IV and ICD-10 criterion A).

2.

Bodily preoccupation, i.e., an absorption with the body and its functioning, e.g., body excretion, physiological function, sensations, appearance, and body performance.

3.

Obsessive rumination with intrusive thoughts and ideas and fears of harboring an illness that cannot be stopped or can be stopped only with great difficulty.

4.

Suggestibility or autosuggestibility: responding with alarm to the slightest hint of illness; alarm may arise from reading about a disease, knowing someone who becomes sick, etc.

5.

Extensive fascination with medical information: reading medical books or journals, reading about medical subjects in an encyclopedia, watching television programs about health or medicine, being interested in news about health, etc.

6.

Unrealistic fear of being infected or contaminated by something touched or eaten, by a person met, etc.

7.

Pathological, excessive health-preserving behavior, i.e., eating special food, extensive exercise, or overdoing other things to keep fit.

8.

Focusing primarily on causality: the patient wants an explanation for the symptoms and is more concerned about the meaning of the symptoms than the distress they cause.

9.

Fear of taking prescribed medication.

These and other candidate symptoms included in the diagnostic research criteria for different somatoform diagnoses were added to the SCAN interview section on physical health. The new questions were integrated in such a way that they appeared to be a natural part of the interview, and the definition of each new symptom was added to the glossary, which is a part of the SCAN interview. Each of the symptoms is rated 0 (“absent”), 1 (“mild to modest preoccupation but no significant distress or impairment”), or 2 (“excessive preoccupation involving severe daily troubles or numerous consultations or self-medication”). In the analysis the symptom ratings 1 and 2 were collapsed. “The duration of hypochondriacal preoccupation” (months) caused by any of the rated symptoms and “interference with everyday activity because of these problems” are additionally rated as separate items in the SCAN. The modified version with definitions of all the symptoms included in this article is available from the authors on request.

The SCAN interviews were conducted by six psychiatric physicians (including T.T.) who were all highly skilled in psychopathological assessment, intensively trained in using the SCAN interview, and certified at the WHO center in Copenhagen. They had all received psychiatric residency training and had at least 2 years of medical and surgical residency experience. During the study they met at least once a week to discuss cases and how to interpret and rate dubious responses and symptoms that seemed to fall between the numeric ratings, and they were free to consult more senior doctors.

Patients scheduled for Thursdays at 1:00 p.m. were asked to give permission for the interview to be videotaped. The videotaped interviews of the eight patients who accepted were rated by all the interviewers, and these ratings showed a high interrater agreement on the presence or absence of any psychiatric diagnosis (kappa=0.86) as well as on the somatoform diagnostic category (kappa=0.82) (unpublished 2003 article by Toft et al.). The interviewers were blinded to the patients’ responses on the screening questionnaires.

Data Analysis

The SCAN interviews were used for computerized DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses with reference to the “present state” (current mental disorder) and “lifetime before” (the patient’s psychiatric history). In this article we present only the data on current mental disorder. The section on physical health containing information on the somatoform disorders and related diagnoses was processed separately in order to make the diagnoses fit the DSM-IV criteria and to analyze the added symptoms.

We processed the data in STATA

(31) and SPSS

(32), and for the latent class analysis we used WINMIRA

(33) and M

plus (34).

Group comparisons were made by chi-square tests for categorical data, and the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test was used for nonnormal continuous data. We estimated prevalence by weighted logistic regression with the observed fraction of second-phase patients as sample weights

(35). To assess the equality of prevalences in subgroups, likelihood ratio tests were performed.

The model selection in latent class analysis was based on different information criteria, with the sample-size-adjusted Baye’s information criterion (SS BIC) as the primary criterion

(34).

In order to assess the goodness of fit of the final selected model, the Pearson chi-square fit statistic and an empirical Pearson chi-square fit statistic were computed.

Two-sided p values are reported.

Ethics

All biomedical studies in Denmark must be approved by the local Science Ethics Committee, which is subject to the laws and regulations laid down by the Danish government. We obtained approval from the Science Ethics Committee of Aarhus County.

All the participating patients received written and oral information and gave written informed consent.

Discussion

Robins and Guze

(36) and later Kendell

(37) listed a range of strategies for establishing the validity of clinical syndromes; the first is to identify and describe the syndrome by “clinical intuition” or by cluster analysis, and the second is to demonstrate boundaries or “point of rarity” between related syndromes by statistical methods. The current DSM-IV hypochondriasis diagnosis rests mainly on “clinical intuition” and tradition, and it is not supported by substantial empirical evidence. To our knowledge, no studies have established a “point of rarity” between the DSM-IV hypochondriasis diagnosis and other somatoform disorder diagnoses, and we did not find support for this in the current study either, as the key symptoms included in the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (criteria A and B) were also common among patients with other somatoform disorder diagnoses. In this study we included a range of symptoms reported to be common or typical for hypochondriasis

(19,

28,

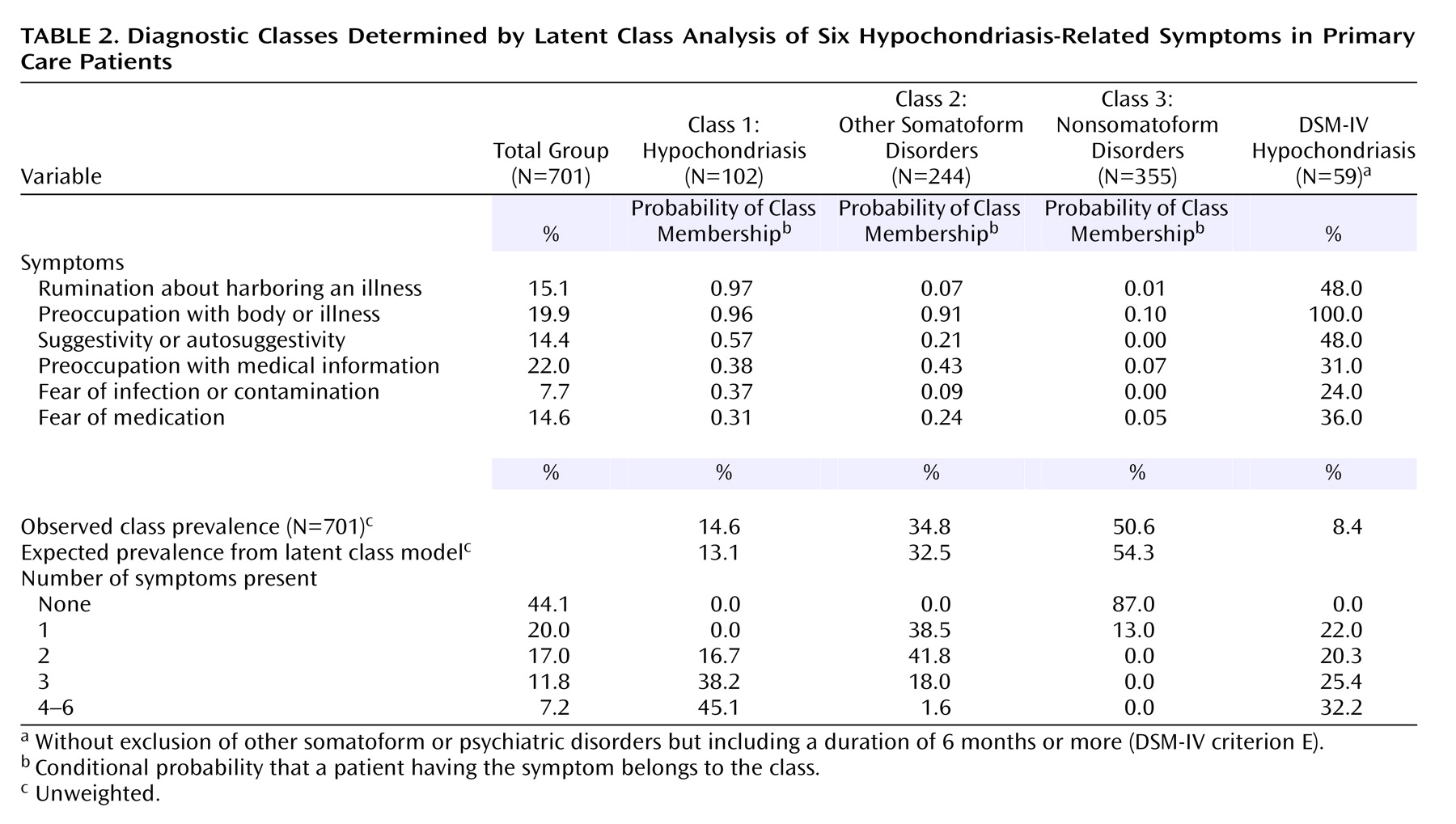

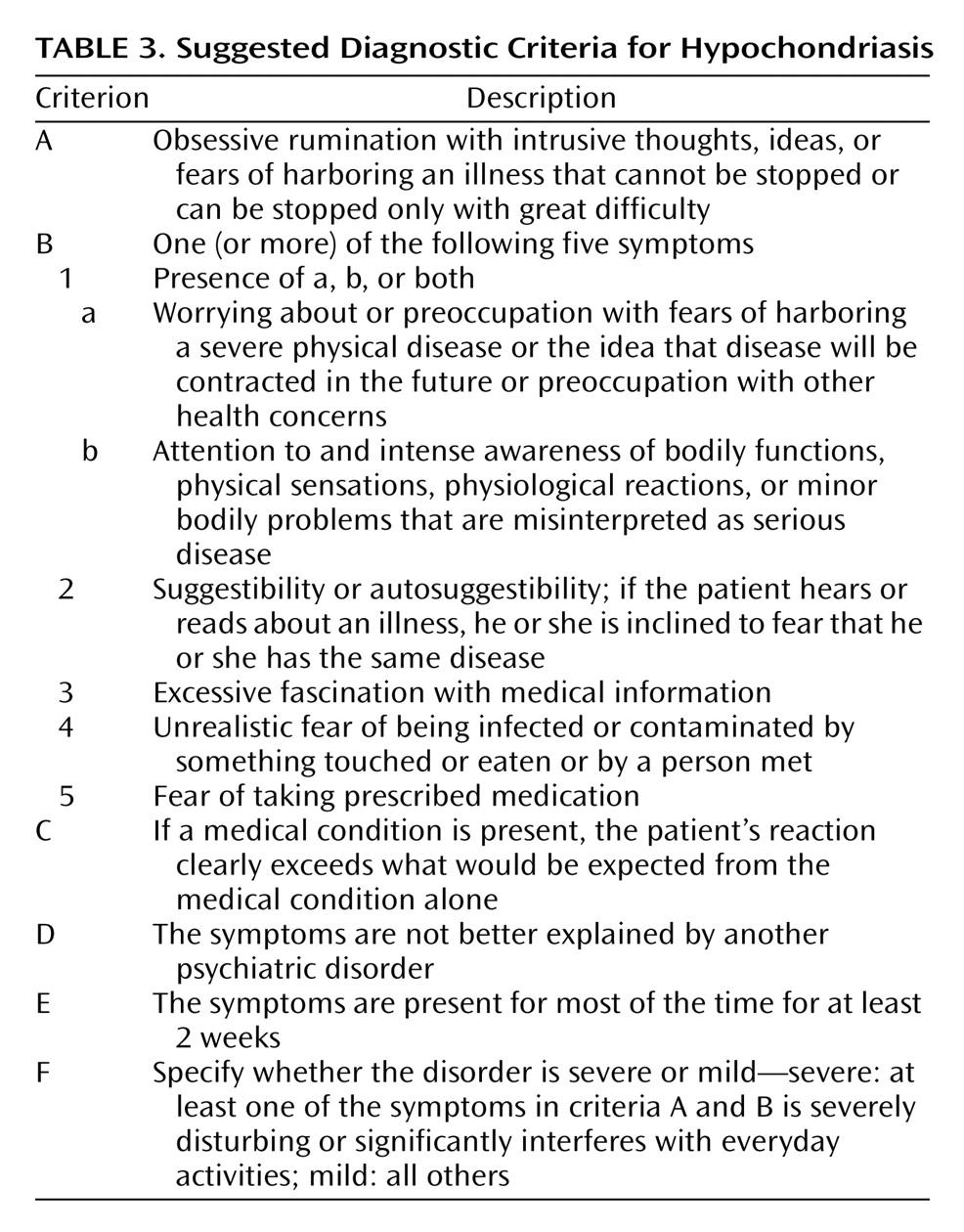

29). We used latent class analysis, a robust statistical method that from a statistical point of view produces a rather clearcut result, establishing a “point of rarity” between classes. Six of the nine symptoms explored fitted satisfactorily into a latent class model with three classes: a hypochondriasis class (class 1), a class of “other somatoform disorders” (class 2), and a class of nonsomatizing patients (class 3). However, even class 3 included some patients with medically unexplained symptoms, and further studies are needed to establish whether this class is truly a nonsomatizing group or a somatoform disorder subgroup without cognitive or emotional symptoms. The suggested diagnostic criteria have to be viewed as preliminary, as the criteria, among other validation procedures, have to be cross-validated in another group of subjects.

From a methodological point of view, the major strength of this study lies in its empirical foundation, in particular its inclusion of a large number of patients gathered in a nonspecialized medical setting. Further strengths include almost complete absence of selection bias, owing to the fact that Danish health care is free of charge, and use of a standardized psychiatric interview, the SCAN, which is state of the art and probably the most advanced and comprehensive diagnostic tool for psychopathology and psychiatric diagnostics available today

(26,

27). The interview section on physical issues comprises questions about all types of somatoform symptoms and hence allows simultaneous study of all known types of somatoform disorders. The interviewers were all highly skilled in psychopathology assessment and intensively trained in using the SCAN interview. The candidate symptoms we added to the SCAN interview were feasible and reliable according to the interviewers.

We expected “bodily preoccupation” to be a distinct hypochondriasis symptom as bodily symptom amplification has been suggested to be a basic mechanism in hypochondriasis

(38,

39), but like “preoccupation with…disease,” it was just as frequent among class 2 patients as among patients with hypochondriasis, and furthermore, the symptoms were frequent among other DSM-IV somatoform disorders. With the addition of “extensive fascination with medical information,” the three symptoms may collectively be viewed as common symptoms of somatoform disorders in general. According to our findings, the missing discriminatory power of these symptoms may therefore be the explanation for the overlap between DSM-IV hypochondriasis and other somatoform disorder diagnoses in the current classification system, as the symptom “preoccupation with…disease” is the key symptom (criterion A) in the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for hypochondriasis.

“Obsessive rumination” proved to have a strong power to discriminate between the patients with hypochondriasis and other patients, and “fear of being infected or contaminated” also appeared to be quite distinctive. These two symptoms outperformed the other symptoms in establishing class 1 hypochondriasis, which raises the question of whether hypochondriasis should be viewed as an OCD spectrum disorder, i.e., “OCD bodily type,” or alternatively, a specific illness phobia. This question cannot be addressed on the basis of this study. None of the three patients with OCD found in this study had class 1 hypochondriasis, and other symptoms atypical for OCD were also common among the patients with class 1 hypochondriasis. It has been suggested that the hypochondriasis diagnosis be moved from the somatoform disorder category to the anxiety disorder category as a “health anxiety disorder,” thus replacing the stigmatizing hypochondriasis label. Despite possible support for this view, it calls for caution regarding premature conclusions; we should keep in mind the discussion in the 1960s and 1970s about whether hypochondriasis should be viewed as a depressive disorder because hypochondriacal worrying is also common in depressive disorders

(40). Instead, a more neutral replacement may be considered, for example the term “valetudin disorder,” which originates from the Greek word

valetudo, meaning “the state of health”

(41).

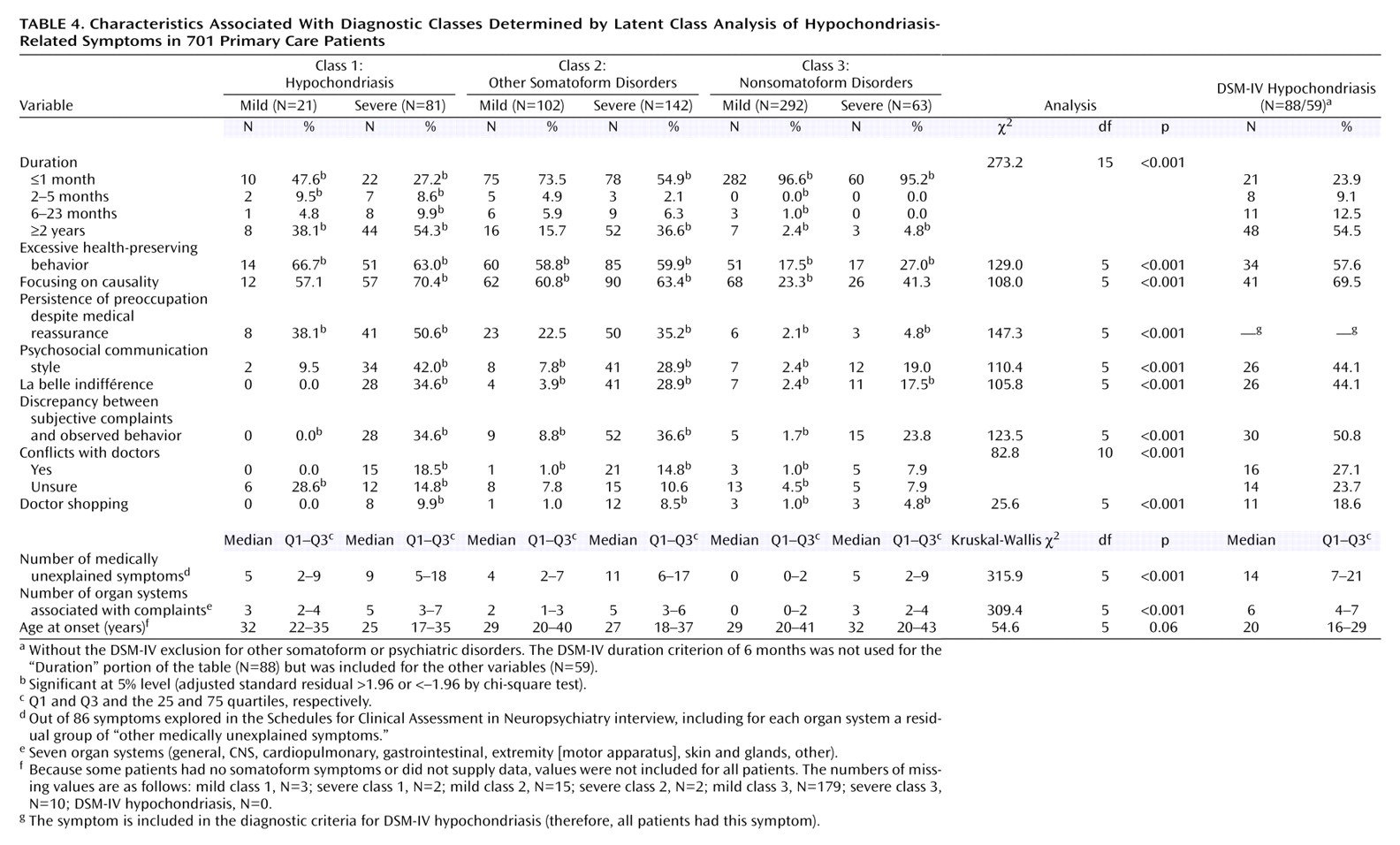

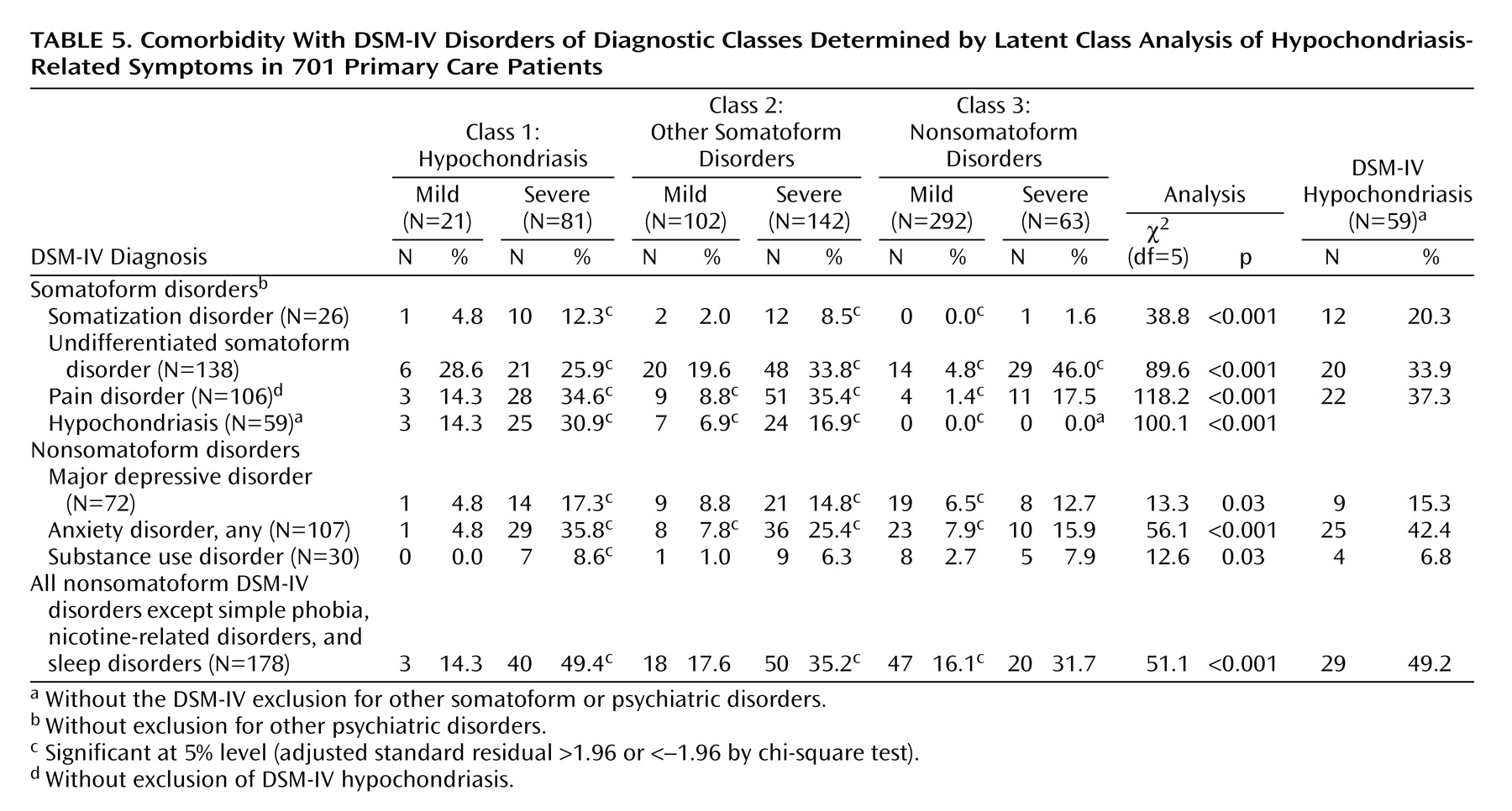

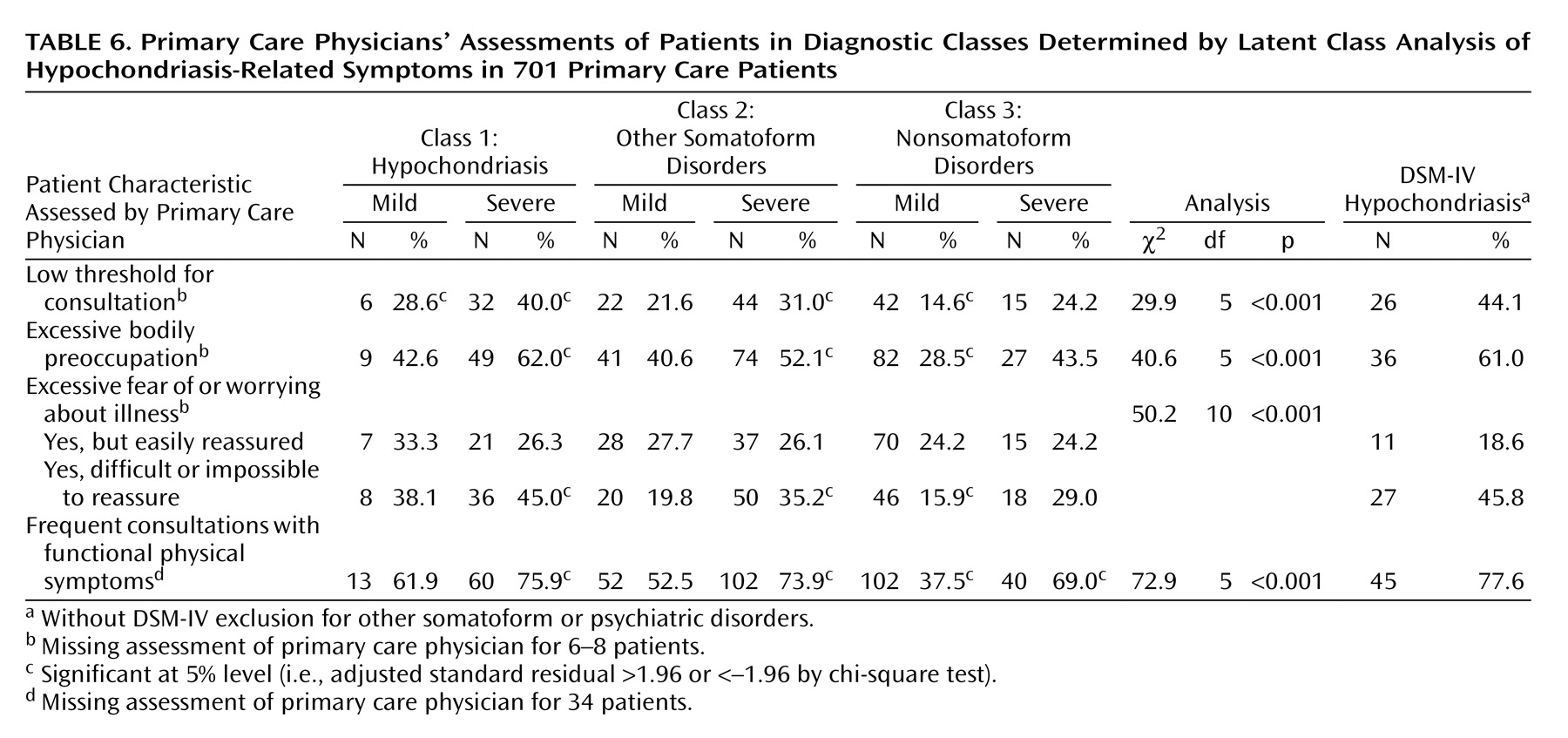

The criteria for class 1 hypochondriasis enjoyed high statistical, clinical, and “face” validity, even compared with the assessments of primary care physicians, but confirmation from daily clinical practice is, of course, needed. It is remarkable that the primary care physicians’ assessments of the patients with severe class 1 hypochondriasis were similar to those for the patients with DSM-IV hypochondriasis despite the fact that class 1 hypochondriasis was about twice as prevalent as DSM-IV hypochondriasis. This may indicate that the class 1 criteria do not pick up more clinically insignificant cases than the DSM-IV diagnosis. Furthermore, it indicates that the DSM-IV hypochondriasis cases not included in the class 1 category in fact may be other somatoform disorders and that they ought to be classified in other subcategories. The class 1 hypochondriasis diagnosis also enjoys the advantage of not being an exclusion diagnosis, i.e., not requiring exclusion of a medical explanation of physical symptoms. It relies solely on positive diagnostic criteria in the form of cognitive and emotional symptoms, hence matching the diagnostic principles of other psychiatric diagnoses. The present study does not allow us to establish whether the full syndrome may emerge as a reaction to a newly diagnosed severe physical disease, as it was conducted in a primary care setting, where the number of such cases was low. We do, however, expect such psychological reactions to be only transient. In patients with the full syndrome, the psychological reaction would probably be clinically significant and encourage intervention, even if the patient also had a severe physical disease.

The class 1 hypochondriasis diagnosis had some comorbidity with other somatoform disorders, but its overlap was smaller than that for DSM-IV hypochondriasis and smaller than that reported in other studies

(17,

42,

43). The magnitude of the overlap between class 1 hypochondriasis and other somatoform disorders was comparable to the overlap between depressive disorder and anxiety disorder (data not reported). The overlap may not necessarily be due to inappropriate diagnostics or overlap of diagnostic criteria; it might also be due to the patients’ suffering from two distinctly independent disorders.

The overlap of DSM-IV hypochondriasis and severe class 1 hypochondriasis was only modest; about one-half of the DSM-IV hypochondriasis cases fell into class 1. Another half fell into class 2, other somatoform disorders. This seems to highlight the poor discriminatory power of the current DSM-IV hypochondriasis diagnosis, as these patients could be split into two distinct groups by latent class analyses of six symptoms. The use of an exploratory approach requires imposition of a minimum of analytical restrictions, and the DSM-IV hierarchical exclusion rules were therefore not used for patients meeting the criteria for more than one diagnosis. Use of the full DSM-IV hypochondriasis criteria, however, made little change (data not reported).

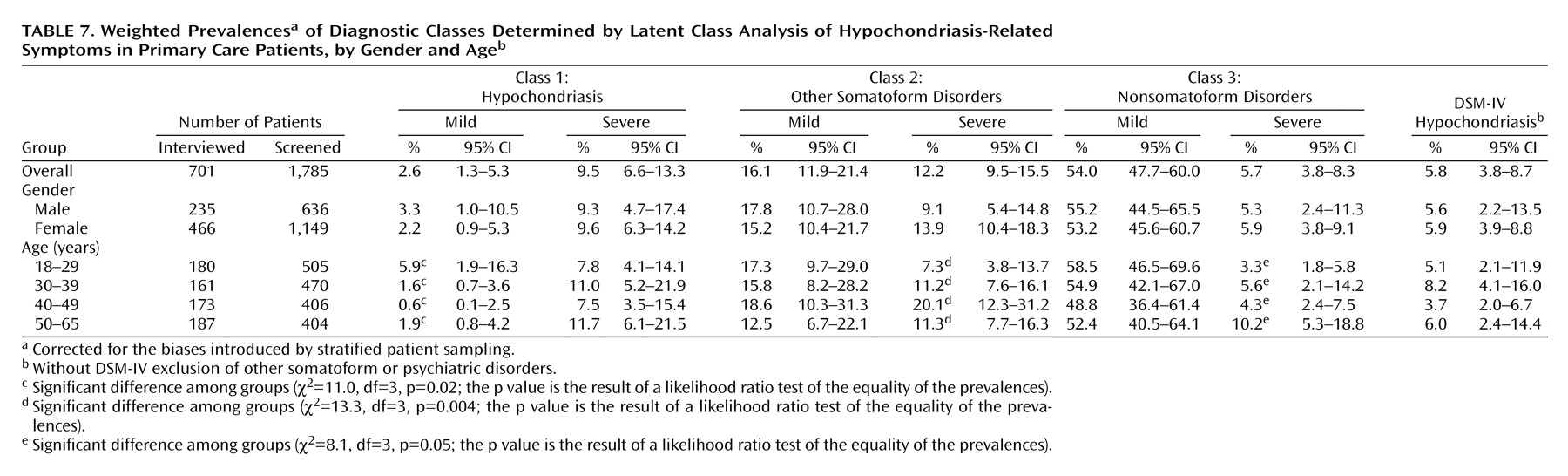

The prevalence of severe class 1 hypochondriasis reached 9.5%, which testifies to its high prevalence among primary care patients. The prevalence of DSM-IV hypochondriasis based on the full criteria (i.e., including the exclusion criteria) was 4.7%, which is higher than in most other studies in primary care, in which prevalence rates have been 0.0%–6.3%

(17,

44).

One of the strengths of the present study lies in its use of a more extensive diagnostic procedure (i.e., the SCAN interview) than was used in other studies and the use of experienced psychiatric interviewers. We included only “incident” cases, i.e., those of patients presenting with new health problems, thus excluding some patients with chronic physical diseases. In accordance with most other studies, we found no gender or age difference in the prevalence of hypochondriasis

(17,

44,

45). About 10% of the primary care physicians in the county participated in the study. This may raise the possibility that a practice selection bias limits the generalizability of the prevalence figures. However, the participating primary care physicians seem to be remarkably representative of the overall population of primary care physicians in the county on most of the variables on which they were compared.

This study focused mainly on class 1 hypochondriasis, but class 2, nonhypochondriasis somatoform disorders, may be just as interesting. This calls for a more profound and focused exploration of the nonhypochondriasis diagnostic categories, which is outside the limits of this article, but we plan to conduct such separate analyses.

The hypochondriasis diagnosis as defined in ICD-10 and DSM-IV has shown to be so restrictive that few patients in primary care fulfill the diagnostic criteria

(17). Gureje et al.

(17) showed that one of the major problems is the symptom “the preoccupation persists despite appropriate medical evaluation and reassurance”(i.e., criterion B), and Barsky et al.

(16) have pointed to the problem of the 6-month time limit (criterion E). The diagnostic criteria suggested in this study do not include these two symptoms and therefore overcome these shortcomings of the current DSM-IV hypochondriasis diagnosis. To replace the duration criterion of 6 months, however, from a purely clinical and not statistical point of view, we suggest the adoption of a severity criterion, i.e., that the symptoms must cause significant distress or impairment in order to be considered clinically significant. However, the patients with “mild” cases (i.e., those with no significant impairment or distress) may still be clinically relevant, especially in a primary care setting. The symptom durations were identical among patients with functional impairment or distress and patients without it, and the latter group also presented multiple medically unexplained symptoms. We may therefore speculate whether the “mild” cases are a type of latent or subclinical hypochondriasis with a high risk of evolving into the manifest clinical syndrome under stressful conditions. Further studies will elucidate the potential implications of the mild syndrome for health care utilization and health-related quality of life and may, if the results are affirmative, warrant inclusion of the mild diagnostic category in the diagnostic classification system as suggested here.

A third point in the validation process, according to Kendell

(37), is to perform follow-up studies to establish a distinct course or outcome. This was not undertaken in the present study, but the included patients are being followed. However, as the symptoms had lasted for a long period in a high fraction of the patients with class 1 hypochondriasis, the present data indicate that the symptoms pursue a distinct course and that the diagnosis remains stable. Kendell

(37) proposed three more strategies: 1) therapeutic trials to establish a distinct treatment response, 2) family studies establishing that the syndrome “breeds true,” and 3) demonstration of the association with some more fundamental abnormalities, i.e., anatomical, biochemical, or molecular. Such validation studies, as well as cross-validation studies in other subjects, have still to be planned.