Bipolar disorder is a common, severe, chronic, and often life-threatening condition. The lifetime prevalences of bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder are 0.8% and 0.5%, respectively (DSM-IV), although more liberal definitions of hypomania identify many more patients with bipolar spectrum disorders

(1). Treatment of bipolar I disorder typically involves pharmacotherapy. However, even in patients with continued adherence to medication regimens, the risk of relapse over a 5-year period has been estimated to be as high as 73%

(2). The risk of relapse is similar in both bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder, is higher in bipolar disorder than in unipolar depression, and persists across the lifespan in patients with bipolar disorder

(1).

Three lines of evidence point to the importance of sleep in bipolar disorder. First, experimentally induced sleep deprivation is associated with the onset of hypomania or mania in a considerable proportion of patients (e.g., reference

3). Second, in a systematic review of 11 studies involving 631 patients with bipolar disorder, sleep disturbance was the most common prodrome of mania (reported by 77% of patients) and the sixth most common prodrome of bipolar depression (reported by 24% of patients)

(4). Third, the sleep/wake cycle has been a core component of theoretical conceptualizations of bipolar disorder. It has been hypothesized that bipolar disorder patients have a genetic diathesis that may take the form of circadian rhythm instability. Psychosocial stresses are proposed to cause disrupted routine and sleep, which, in turn, disrupts the vulnerable circadian rhythm and triggers an episode

(5,

6).

As a result of these findings, psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder, such as cognitive behavior therapy and interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, include education and monitoring of the sleep/wake cycle and include the aim of promoting regularity in daily activities. Although these interventions have been shown to be efficacious adjuncts to pharmacotherapy

(7,

8), they focus on a wide variety of behaviors, making them potentially time-consuming, and have not yet drawn on the large and impressive literature documenting the effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of insomnia

(9).

In the present study, we sought to establish whether core components of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia have the potential to enhance interventions for bipolar disorder patients by providing a specific emphasis on sleep. Three components were investigated: 1) stimulus control to reverse maladaptive conditioning between the bed/bedroom and not sleeping by limiting sleep-incompatible behaviors within the bedroom environment, 2) sleep hygiene to provide education about behaviors that interfere with sleep, and 3) cognitive therapy to alter unhelpful beliefs about sleep. An additional aim of this study was to observe the sleep-related functioning of bipolar disorder patients in the nonacute, so-called euthymic or interepisode phase of the disorder. Although it is recognized that patients with bipolar disorder often continue to be symptomatic between episodes

(10), to our knowledge the research to date on sleep disturbance has often focused exclusively on sleep just prior to and during episodes of mania or depression.

Discussion

One aim of the present study was to investigate the sleep-related functioning of euthymic bipolar disorder patients. The rationale was that while patients with bipolar disorder are known to be symptomatic even when euthymic

(10), to our knowledge there are no published data documenting their sleep/wake cycle during nonacute periods, despite the importance of sleep in theories about bipolar disorder (e.g., references

5,

6). Taken together, the sleep estimates from the retrospective, prospective, subjective, and objective sources in the current study indicate that sleep disturbance was, indeed, a significant problem in the bipolar disorder group, even when the patients were euthymic. Seventy percent of the bipolar disorder group had a clinically significant sleep problem, and 55% met the strict diagnostic criteria for insomnia (excluding criterion D). These findings add to previous evidence indicating that bipolar disorder patients may experience considerable symptoms during periods when their illness is nonacute

(10). Furthermore, the sleep of the bipolar disorder patients, as a group, was more similar to that of the insomnia patients than to that of the good sleeper group on most measures. This pattern was even more evident in analyses comparing the 11 patients with bipolar disorder plus insomnia with the patients who had insomnia only. However, we make these observations cautiously, as the number of subjects was small; hence the study may have lacked sufficient statistical power to detect minor but important differences.

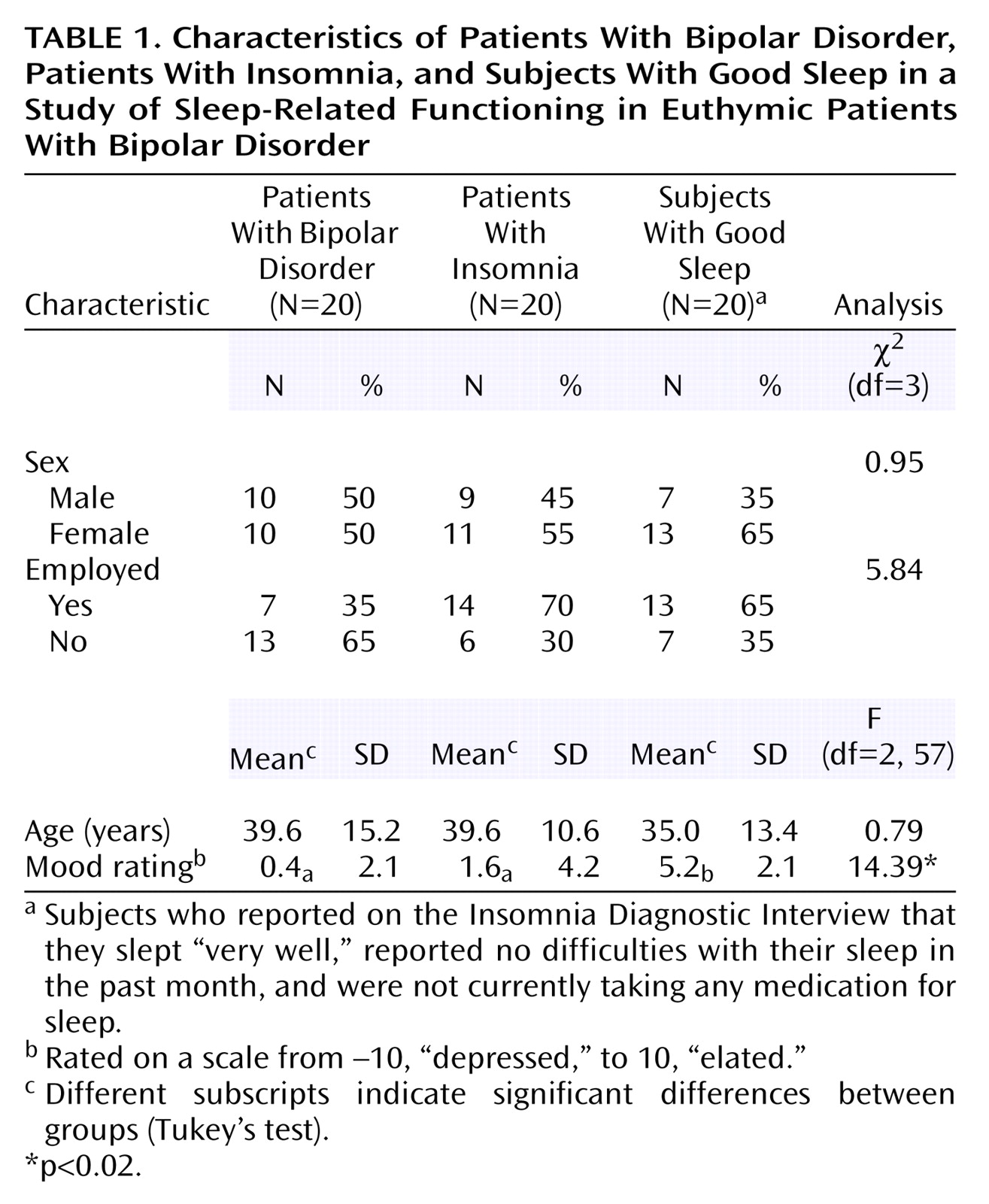

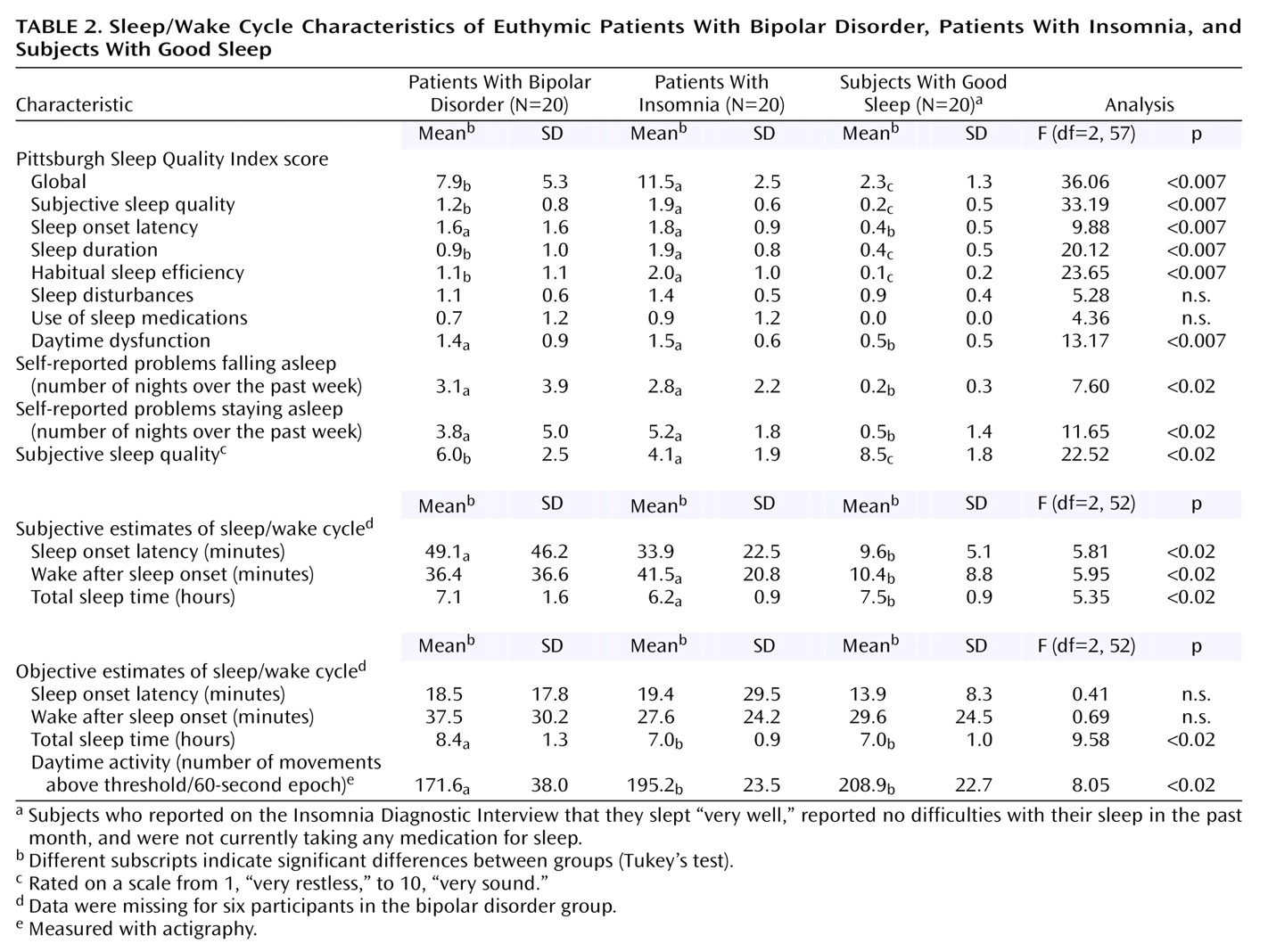

The bipolar disorder and insomnia groups were heterogeneous in 1) their sleep characteristics (see standard deviations in

Table 2), 2) the medications they were taking, and 3) their patterns of comorbidity. However, correlations between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index global score and demographic variables were not significant, suggesting that baseline differences in demographic characteristics were unrelated to sleep problems.

Previous research has established a discrepancy between subjective and objective sleep estimates in patients with insomnia, who tend to overestimate the time it takes them to get to sleep (sleep onset latency) and underestimate how much sleep they obtain overall (total sleep time) (e.g., references

40,

41). In the present study, the bipolar disorder group showed a similar pattern of results: they overestimated how long it took them to fall asleep (by an average of 40.6 minutes [

Table 2]) and they underestimated how much sleep they obtained overall (by an average of 1.3 hours [

Table 2]). Although these findings should be verified by using polysomnography as the objective sleep measure, we offer several tentative interpretations. First, research on insomnia has highlighted that cognitive arousal is a mechanism that underpins the tendency to misperceive sleep in insomnia

(42). Given the results for the Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire and Dysfunctional Attitudes and Beliefs About Sleep Questionnaire in the present study, it is possible that this mechanism also operates to distort the perception of sleep in patients with bipolar disorder. Second, misperception of sleep may contribute to anxiety because it leads the person to believe that the sleep he/she is getting is inadequate. Because anxiety is antithetical to sleep, this difficulty may then serve to maintain the insomnia

(43). A behavioral intervention can reduce the tendency to underestimate the amount of sleep obtained and reduce sleep-related anxiety in insomnia patients

(44); similar results from use of such interventions would be predicted in euthymic bipolar disorder patients.

Finally, the bipolar disorder group had lower daytime activity levels, relative to both the insomnia group and the good sleeper group. The lower activity level in the bipolar disorder group may be related to their use of medication and may not be important for sleep. On the other hand, it could also be relevant to their insomnia. For example, lower activity levels might serve to maintain nighttime sleep problems, as the patients may not be sufficiently tired to get to sleep. The latter finding raises the possibility that components from the behavioral activation intervention

(45) may be worth considering as an adjunct to psychosocial treatment for bipolar disorder.

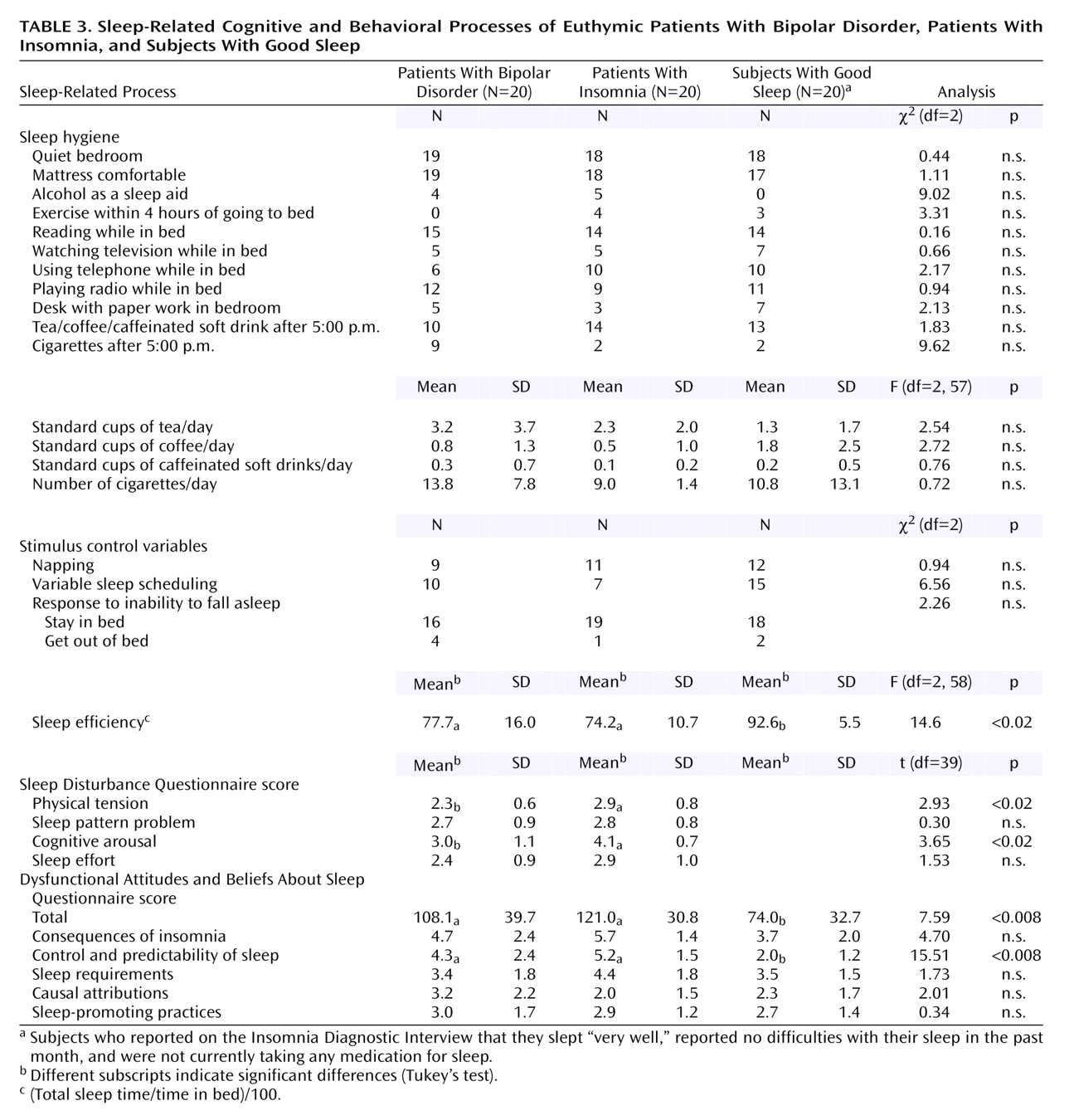

An additional aim of this study was to assess the constructs that underpin three components of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia. The finding that the insomnia group had poorer sleep efficiency is consistent with previous findings (see reference

25). Sleep efficiency was the only stimulus control variable to reach significance in the comparison of bipolar disorder patients and good sleepers. This finding raises the possibility that improved sleep efficiency, by means of a stimulus control intervention, may be a useful objective for patients with bipolar disorder

(46,

47). By contrast, the bipolar disorder group did not have poor sleep hygiene. This finding brings into question the value of sleep hygiene training in the treatment of insomnia in bipolar disorder patients. By analogy with behavioral approaches to primary insomnia

(32), our analysis represents a first step in the process of empirically deriving appropriate interventions for the treatment of sleep disturbance in patients with bipolar disorder.

The results from the Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire and Dysfunctional Attitudes and Beliefs About Sleep Questionnaire were striking. The most commonly endorsed item on the Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire—“I can’t get in a proper routine”—confirms the importance of regularizing the sleep/wake cycle, a treatment component that is already included in cognitive behavior therapy and interpersonal and social rhythm therapy for bipolar disorder

(7,

8). The other most frequently endorsed items (“My mind keeps turning things over” and “I am unable to empty my mind”), along with the relatively high score on the cognitive arousal subscale of the Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire, parallel results found in the insomnia groups in this study and in previous research

(32,

37). These findings raise the possibility that excessive cognitive arousal while trying to get to sleep may be one process that maintains the sleep disturbances experienced by euthymic bipolar patients.

The bipolar disorder group held a level of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep that was comparable to that of the insomnia group and significantly higher than that of the good sleepers. Although these findings need to be confirmed with a larger group of subjects, we found that holding more dysfunctional beliefs about sleep was associated with more severe sleep disturbance (r=0.76). This association is consistent with previous research findings

(48) and suggests that dysfunctional beliefs about sleep may be important in the maintenance of insomnia in patients with bipolar disorder. In addition, relative to the good sleeper group, both the bipolar disorder group and the insomnia group scored higher on the control and predictability of sleep subscale of the Dysfunctional Attitudes and Beliefs About Sleep Questionnaire. The highly scored items of this subscale for the bipolar disorder group were “I am worried that I may lose control over my abilities to sleep,” “I can’t ever predict whether I’ll have a good or poor night’s sleep,” and “I get overwhelmed by my thoughts at night and often feel I have no control over this racing mind.” In addition to confirming the Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire findings just discussed, these items suggest that the bipolar disorder subjects are anxious and fearful about their sleep. Informally, most of the patients in the bipolar disorder group reported that the cause of their anxiety about sleep was the awareness that sleep loss can herald an episode of mania or depression.

The clinical implications of these findings are threefold. First, they raise the possibility that interventions designed to reduce cognitive arousal while trying to get to sleep may be warranted

(49). Second, as anxiety and fear are antithetical to sleep onset, they are worthy targets for intervention. Future studies should explore the utility of education

(25,

50) and behavioral experiments

(51) designed to alter dysfunctional beliefs. Finally, when working with patients to enhance their ability to recognize prodromes and develop effective coping strategies for prodromes

(8), care should be taken not to increase anxiety about sleep.