Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental disorder that potentially follows an event in which the individual experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with either actual or threatened loss of life or serious injury invoking a response of fear, helplessness, or horror. According to DSM-IV, PTSD symptoms are subdivided into three categories: reexperiencing of the trauma, numbing of affect and avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, and symptoms of excessive arousal not present before the event. Since the introduction of PTSD to the psychiatric nomenclature, a growing amount of research has centered on diagnosis, course, and treatment of the disorder. However, only a small subset of individuals who have been exposed to a traumatic event goes on to develop PTSD or other disorders (e.g., major depression, anxiety disorders)

(1). The estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD ranges from 1.3% in Germany

(2) to 7.8% in the United States

(3). In contrast, 89.6% of citizens in the United States are exposed to at least one traumatic event at some time in their lives

(4). Thus, PTSD is a possible but not inevitable consequence of trauma exposure. Because initial evidence suggests the potential benefits of early intervention shortly after trauma

(5–

7), accurate identification of specific risk and protective factors is needed to provide effective treatment to those who are likely to develop long-term trauma-related psychopathology.

Aside from the most salient predictor of PTSD, which is the nature of the traumatic event itself, three other risk factors were consistently identified across studies in a meta-analysis by Brewin et al.

(8): psychiatric history, family history of mental disorders, and childhood abuse. In addition, personality traits (e.g., hostility, neuroticism, self-efficacy) were also identified as predictors of PTSD symptoms

(8,

9). However, it is noteworthy that the vast majority of previous studies have used retrospective designs with respect to possible risk factors, and the potential for distortion of such factors in cross-sectional research is well known from a methodological point of view. Moreover, retrospective data of trauma survivors are influenced by typical PTSD symptoms, such as avoidance and amnesic or dissociative symptoms. Thus, a putative risk factor may merely be a consequence of the disorder, not one of its causes.

Until recently, few studies prospectively examined the development of mental disorders after exposure to trauma. In most of these studies, psychological and biological data were collected in the immediate aftermath and at subsequent time points after trauma exposure (e.g., assault, motor vehicle accident) to identify mechanisms that are predictive of PTSD symptoms. It is interesting to note that the salient predictors of PTSD known from retrospective studies seem to have poor predictive value for the development of the disorder when they are assessed in a prospective design

(10). For example, discriminant function analysis failed to show effects of past psychiatric history, prior trauma, or intrusive symptoms in victims of motor vehicle accidents in the immediate aftermath of a trauma

(11,

12). In contrast, biological variables in the acute peritraumatic phase have been shown to more accurately predict chronic PTSD

(1). For example, lower cortisol levels

(11,

13) and higher resting heart rates

(14,

15) shortly after motor vehicle accidents were shown in persons who developed PTSD at a follow-up time, relative to those who did not.

However, these prospective posttraumatic data do not allow the identification of predisposing factors. Is it the trauma itself or pretraumatic vulnerability that gives rise to the altered biological and psychological mechanisms immediately after trauma? And if these early posttraumatic mechanisms have been shown to have high predictive value for the development of PTSD symptoms and other mental disorders, would the identification of preexisting risk factors allow a better understanding of the development of trauma-related disorders? The analysis of pretraumatic risk factors may best be carried out with a prospective, longitudinal study design that includes data from the period before exposure to trauma, which are used to determine whether any of the factors predict subsequent PTSD symptoms. Whereas pretraumatic factors of primary victims (e.g., persons who have experienced rape or a motor vehicle accident) are very difficult to establish conclusively for methodological reasons, members of high-risk populations for trauma-related disorders who are often exposed to traumatization provide an adequate sample. Professional firefighters are regularly engaged in intense traumatic events, including exposure to gruesome injuries or death and unpredictable, dangerous situations

(16–

21). The estimated prevalence of PTSD is 22.2% in American firefighters and 17.3% in Canadian firefighters

(22). Similarly, an estimated 18.2% of German firefighters met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD

(23). In view of the fact that a community study found the highest risk of PTSD in victims of assaultive violence to be 20.9%

(4), it is clear that firefighters represent a population at high risk for the development of PTSD symptoms.

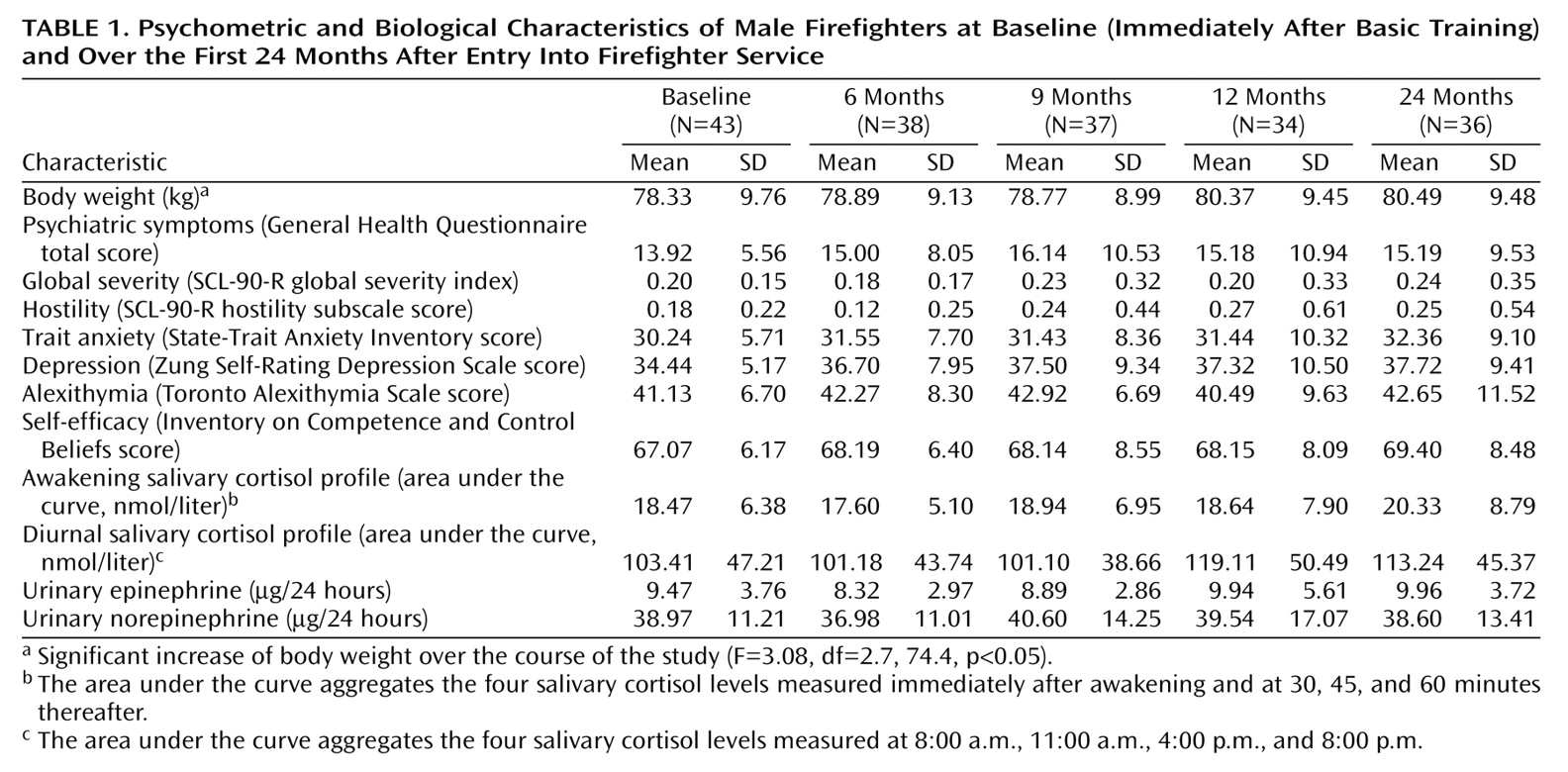

Although there is still considerable need for a better understanding of the development of chronic psychopathology after a traumatic event, to date, even less attention has been given to the underlying preexisting vulnerability mechanisms. In a prospective, longitudinal study design, subjective (personality traits, psychopathological symptoms) and neuroendocrine (salivary cortisol, urinary catecholamines) characteristics were repeatedly assessed. In this study we sought to answer the question: What characteristics present at the time before exposure to traumatic stress may predict PTSD symptoms and other psychopathological symptoms in a high-risk population over the course of 2 years?

Discussion

Although exposure to trauma is common, PTSD and other mental disorders after trauma are relatively rare. The core methodological issue in the growing field of research on traumatic stress is to test which factors precede psychopathological symptoms that emerge after trauma in order to allow early and specific diagnosis and intervention. The best method for identifying variables that increase the risk for trauma-related disorders may be to administer a battery of measures to a large number of individuals before their exposure to trauma and to determine whether any measures predict subsequent PTSD symptoms

(9). Professional populations at high risk for trauma-related disorders (e.g., firefighters, members of the military) are regularly engaged in traumatic events and thus provide model groups in which to explore preexisting differences that constitute risk factors for PTSD symptoms.

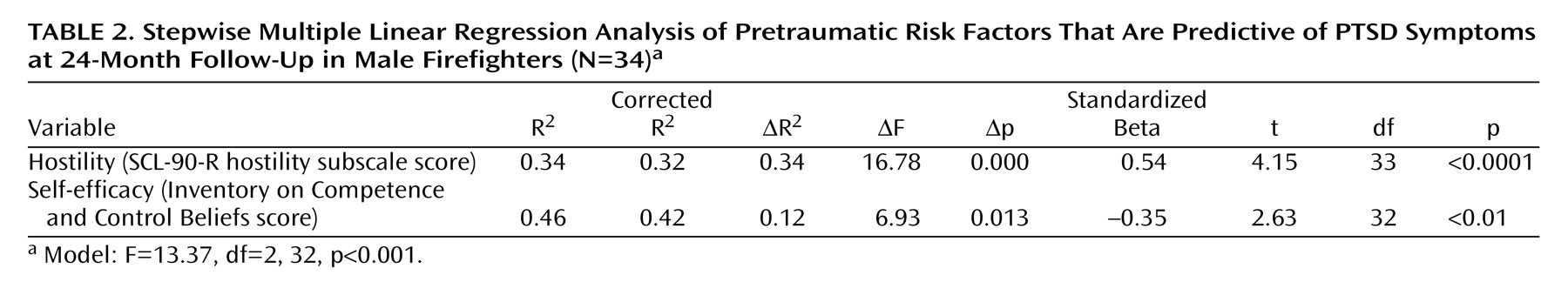

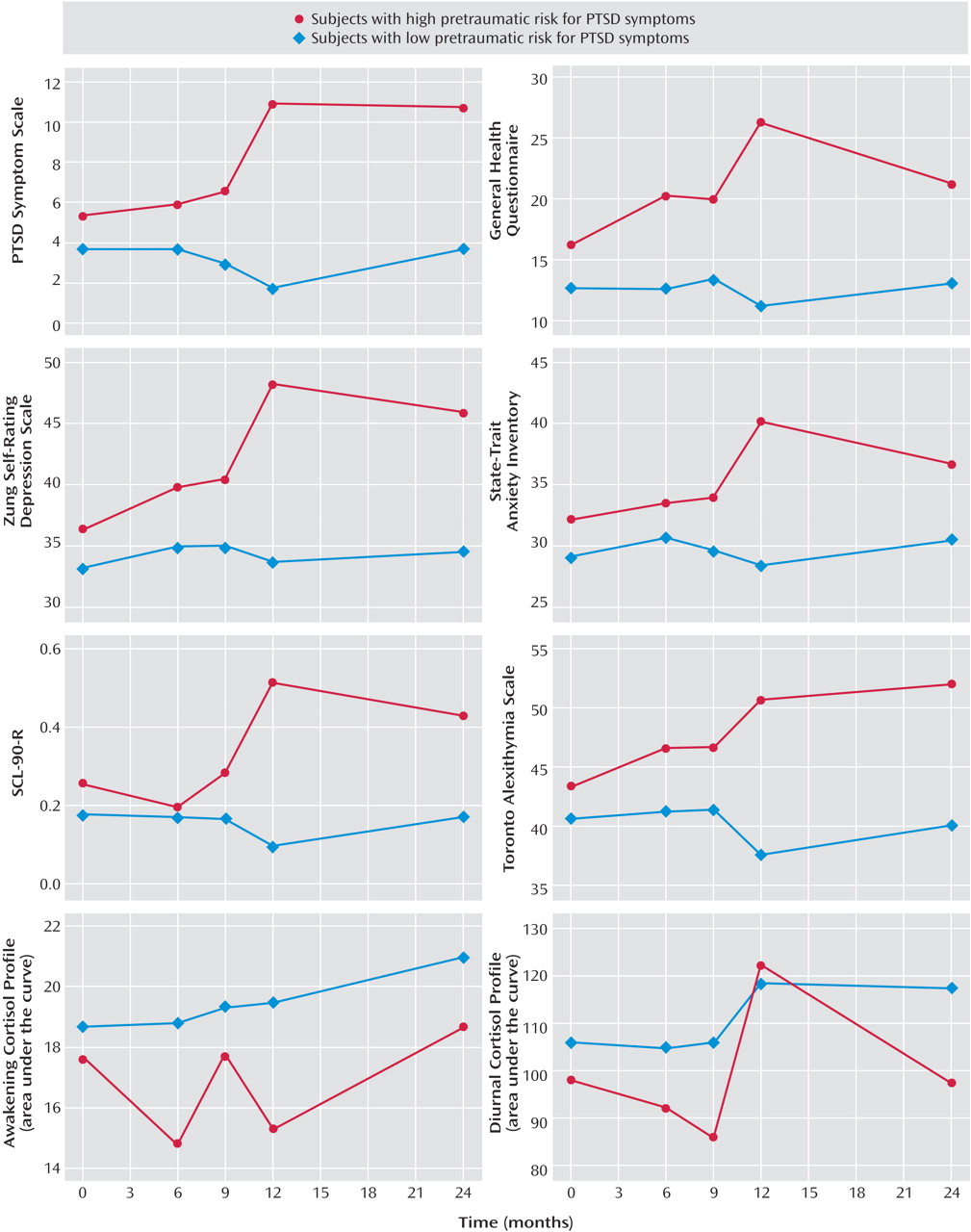

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to investigate prospectively the predictive power of both psychological and biological characteristics before trauma exposure in the development of subsequent posttraumatic stress symptoms. The results of the multiple regression analysis show that the combination of preexisting high levels of hostility and low levels of self-efficacy is a strong predictor of the development of PTSD symptoms in the high-risk population of firefighters. The presence of both risk factors at baseline accounted for 42% of the variance in posttraumatic stress symptoms at 2-year follow-up. Moreover, firefighters with both of these personality characteristics at baseline had a steady increase during the 2-year period in scores on measures of PTSD symptoms, depression, anxiety, general psychological morbidity, global severity of symptoms, and alexithymia. The strongest increase in all of the psychopathological symptoms assessed took place between 6 and 12 months after job entry (

Figure 1). It is noteworthy that during that period, the fire departments endeavored to confront the probationary firefighters with stressful on-duty events in order to test their eligibility for the job (see Method). In contrast, subjects with either low levels of hostility or high levels of self-efficacy or both protective traits showed no increase in psychopathological symptoms, suggesting a significant effect of these personality factors on the development or prevention of stress-related symptoms.

The present data support and extend the clinical evidence regarding the role of personality traits in PTSD. Higher levels of hostility and anger have been associated with the development of PTSD symptoms in combat veterans; victims of violent crime, sexual assault, and accidents; and political prisoners

(49–

63). For example, anger accounted for more than 40% of the variance in PTSD symptoms in Vietnam veterans

(60). Furthermore, lower levels of self-efficacy have previously been related to PTSD symptoms

(64–

66). Individuals with PTSD report lower self-efficacy levels than healthy comparison subjects, although traumatized individuals without PTSD do not differ in self-efficacy from comparison subjects

(66). However, all of these studies of the predictive power of alleged risk factors began only after subjects had been exposed to trauma. The design of such studies makes it difficult to differentiate between consequences and causes.

As yet, only a small number of prospective, longitudinal studies have been conducted in this area, and they have primarily examined archival data (e.g., military records) collected pretrauma. In combat veterans, specific preexisting personality traits were shown to predict PTSD symptoms

(67–

69). Schnurr et al.

(69) found that higher scores on the MMPI paranoia, hypochondriasis, psychopathic deviate, and masculinity-femininity scales predicted PTSD symptoms in male college graduates who later served in the Vietnam War. Bramsen et al.

(67) reported that higher scores on a personality measure of negativism (akin to neuroticism) predicted subsequent PTSD symptoms among Dutch veterans who took part in the United Nations Protection Force mission in the former Yugoslavia. These initial prospective findings suggested that pretrauma personality traits are predictive of later development of PTSD symptoms after trauma exposure. Moreover, there is evidence that lower intelligence levels precede rather than follow the development of PTSD symptoms in combat veterans

(70).

The identification of risk factors may provide clues regarding underlying mechanisms and could help in building new strategies to prevent the development of a disorder

(71). It is surprising that little attention has been directed toward the role of protective or resilience factors against stress-related psychopathology. For example, individuals with low hostility ratings may be those who have better social coping abilities. A possible consequence of a high level of hostility, on the other hand, is social isolation or lack of social support. It should be noted within this context that recovery from PTSD is significantly influenced by the ability to preserve social support networks

(8,

72–77), and in turn, social support might be an important factor for maintaining high levels of self-efficacy

(73). As self-efficacy refers to an individual’s feeling of confidence that they can perform a desired action

(78–

80), individuals with a high level of self-efficacy may be able to impose meaning on their traumatic experiences, thereby fostering recovery from them. Conversely, low self-efficacy might render life more unpredictable and uncontrollable from the perspective of the survivor of a trauma, thereby increasing the risk for long-term trauma-related psychopathology. Accordingly, the intense exposure to stressful events experienced by probationary firefighters 6–12 months after job entry led to a strong increase in all psychopathological symptoms in the firefighters who had a high level of hostility and a low level of self-efficacy, while the low-risk group showed no changes during this period (

Figure 1). Future prospective studies should further explore powerful protective psychological factors (e.g., social support, self-efficacy), other personality factors, and possible underlying neurobiological mechanisms (e.g., neuropeptide oxytocin) in the development of stress-related symptoms

(81–

83).

In the present study, we did not find significant alterations in salivary cortisol and urinary catecholamines. Although awakening cortisol concentrations were consistently lower in the high-risk group of firefighters (those with a high level of hostility and a low level of self-efficacy) than in the low-risk group during the 2-year period, the difference did not reach statistical significance, possibly owing to the small number of subjects. Most studies of chronic PTSD have demonstrated that PTSD is associated with distinct endocrine modifications, primarily involving a highly sensitized hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis characterized by decreased basal cortisol levels and increased negative feedback regulation (e.g., references

37,

84–88). These studies raise the question of when in the course of adaptation to trauma are low basal cortisol levels first observable. For example, McFarlane et al.

(11) demonstrated that subjects who had developed PTSD 6 months after a motor vehicle accident had significantly lower cortisol levels within hours after the trauma, compared to subjects who subsequently developed major depression or those who did not develop a mental disorder. Resnick et al.

(89) found lower cortisol levels immediately after rape only in women with a prior history of rape or assault, although cortisol levels did not predict the subsequent development of PTSD in these women. However, the course of cortisol levels pretrauma has not yet been examined. One possible explanation for the difference in our endocrine findings, compared with those of previous studies, might be a differential extent of psychopathological symptoms. In the present study, we used a continuous measure to cover the range of PTSD symptoms (e.g., references

90–94). Future longitudinal studies should additionally use standardized diagnostic interviews at all time points to measure symptoms of PTSD. Moreover, we did not measure PTSD symptoms related to a specific traumatic event. Despite these limitations, our results do suggest that both cortisol and catecholamine levels before trauma exposure did not predict the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms over the course of 2 years. Obviously, additional prospective, longitudinal studies that use neuroendocrinological and neuroimaging techniques and that include large study groups and start before exposure to trauma are needed to further evaluate the course of biological mechanisms in the adaptation to trauma.

An important question to be raised is to what extent the current data may be generalized to other populations. The largest group of traumatized individuals in which PTSD symptoms have been studied is male combat veterans. The present study was conducted in a population of male professional firefighters. It is important to note that the risk factors discovered in male high-risk populations cannot be applied directly to other groups, including the general population, assault and rape victims, victims of accidents, or victims of natural disasters. Because of the low predictive value of salient predictors of PTSD symptoms in prospective studies, such as past psychiatric history, prior trauma, and intrusive, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptoms in the immediate aftermath of the trauma

(11,

12,

95), a new vulnerability model that includes pretrauma risk factors, type of trauma, and trauma responses is warranted.

A better understanding of pretraumatic risk factors would undoubtedly have important clinical implications with regard to the development of trauma-related disorders. This study supports the evidence for a strong predictive role of personality traits in the development of PTSD symptoms and comorbid psychopathological symptoms. Ideally, it would be desirable for future studies to further explore the interrelationships between possible preexisting personality factors and psychobiological mechanisms in the development of PTSD in order to integrate pre- and posttraumatic factors of vulnerability. For example, it might be speculated that a smaller hippocampus

(96) somehow alters the ability for cognitive buffering against stress, resulting in both dysfunctional personality traits (e.g., low level of self-efficacy) and HPA axis alterations (e.g., low cortisol level). Alternatively, there could be multiple pathways for developing PTSD symptoms, and the course may or may not involve all of the mechanisms mentioned earlier. Accordingly, there is most likely no linear relationship between one possible risk factor and subsequent trauma-related symptoms.

Although the reported results need to be replicated to allow firm conclusions to be drawn, quantification of hostility and self-efficacy as risk or protective factors may eventually help the clinician and specific organizations to target individuals at high risk of developing trauma-related disorders (e.g., firefighters, police, military) at an early stage. One critical question that needs to be answered is whether specific psychological and biological characteristics could be used as exclusionary factors for some types of professions in order to protect individuals who wish to enter these professions. Finally, the results may indicate that coping skills training (e.g., anger/hostility management, self-efficacy training) could be helpful for primary and secondary prevention in high-risk populations.