A number of family studies have reported that suicidality runs in families

(1–

14). Although familial aggregation may not be interpreted as equivalent to genetic inheritance, results from twin and adoption studies have suggested that there may be an underlying genetic component

(15–

20). Previous studies further suggest that familial transmission of suicidality seems to be independent of comorbid mental disorders

(5,

10–

13,

16,

21–23).

However, there are some critical points. First, most of these studies included clinically referred samples. This may be crucial insofar as familial aggregation in treatment samples could be attributable to treatment bias and thus may be limited to a subgroup of severely ill patients in treatment

(24). For prevention and intervention, however, it is important to demonstrate that these associations can also be found in representative community samples. Second, for completed suicide, most studies used the psychological autopsy method. Inherent to this approach is the potential recall bias of the informants. To date, only a few studies have addressed the familial transmission of suicidality in nontreatment samples

(13,

21,

25,

26). Although the results of these studies support the hypothesis of familial aggregation, there is still uncertainty about the strength of the association in the community. Furthermore, no data are yet available from representative samples concerning the impact of familial suicidality on the age of the first manifestation of suicidality in offspring. Such information would be of major interest from a preventive point of view, since it allows for identifying not only high-risk groups but also high-risk periods that are risk-group specific for the first manifestation of suicidality.

The goal of this report is to increase our understanding of the familial transmission of suicidality by evaluating, based on a representative community sample, the associations between suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in mothers and various aspects of suicidality (frequency of ideation, attempts, and age at onset) in offspring.

Results

Lifetime Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts

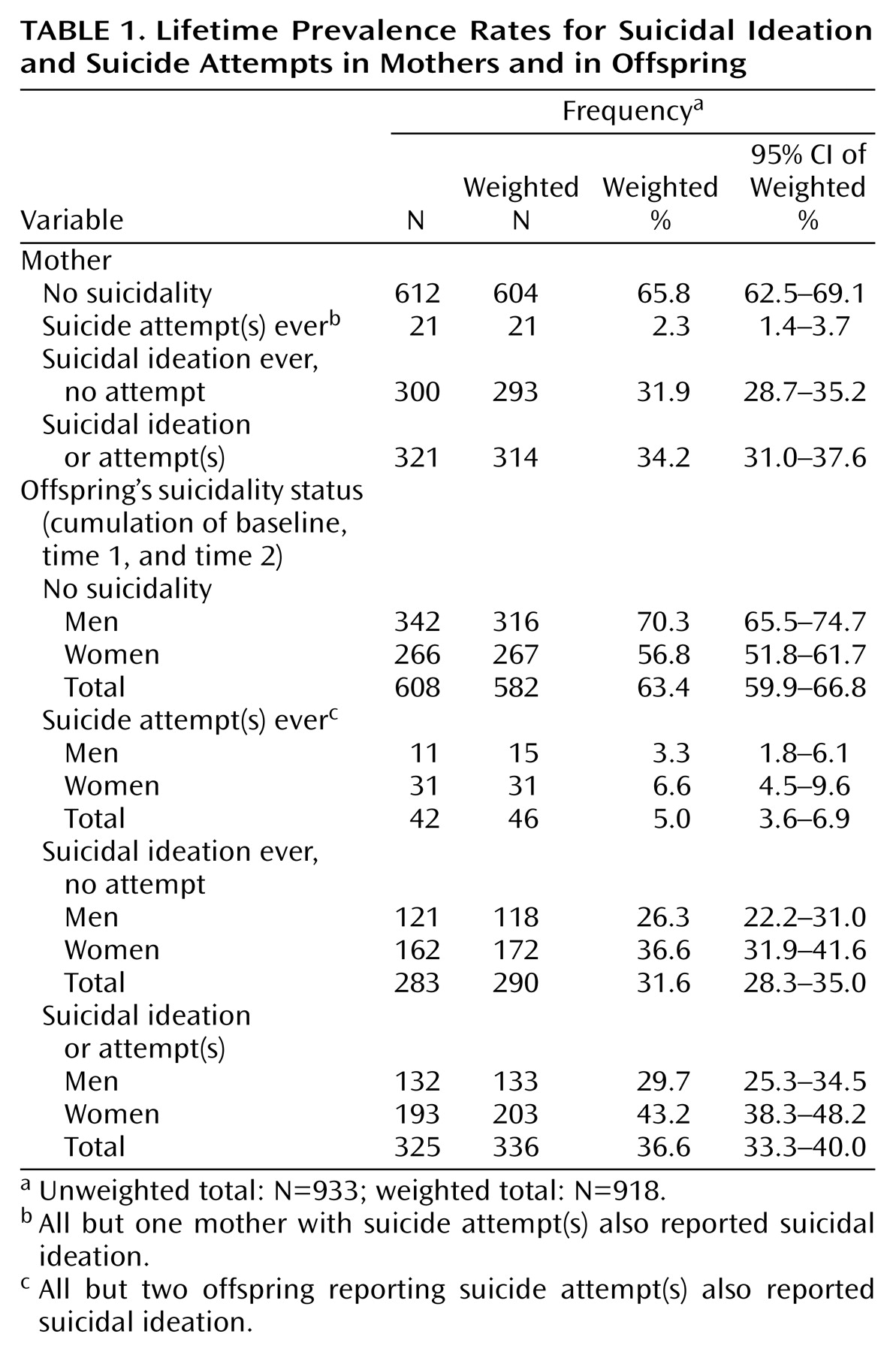

About one-third of the mothers reported lifetime suicidal ideation, whereas the rate of suicide attempts in the mothers was 2.3% (

Table 1). Comparably, about one-third of the study sample of adolescents reported suicidal ideation during their lifetimes, and 5.0% reported suicide attempts. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were more common in female than in male offspring: suicidal ideation: 36.6% versus 26.3% (odds ratio=1.7, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.2–2.4), suicide attempts: 6.6% versus 3.3% (odds ratio=2.5, 95% CI=1.1–5.2).

Sociodemographic Characteristics

With regard to suicide status, the mothers did not differ in age (mean age of the mothers without suicidality=46.8 years, SD=5.2; the mothers with suicidal ideation only=46.5 years, SD=5.2; and the mothers with suicide attempts=46.3 years, SD=5.8. However, differences were found regarding current living situation (with partner: 85.3% for the mothers without suicidality, 76.9% for the mothers with suicidal ideation only, and 50.1% for the mothers with suicide attempts), employment status (employed: 75.6% for the mothers without suicidality, 71.4% for the mothers with suicidal ideation only, and 77.9% for the mothers with suicide attempts), and education level (middle/higher education: 71.1% for the mothers without suicidality, 71.6% for the mothers with suicidal ideation only, and 42.2% for the mothers with suicide attempts). The offspring did not differ notably by maternal suicidality in sex (females: 50.3% among the offspring of mothers without suicidality, 53.5% among the offspring of mothers with suicidal ideation only, and 41.8% among the offspring of mothers with suicide attempts) or age distribution at the second follow-up (mean age: 18.7 years [SD=1.2] in the offspring of mothers without suicidality, 18.9 years [SD=1.2] in the offspring of mothers with suicidal ideation only, and 18.7 years [SD=1.0] in the offspring of mothers with suicide attempts).

Mother-Offspring Associations

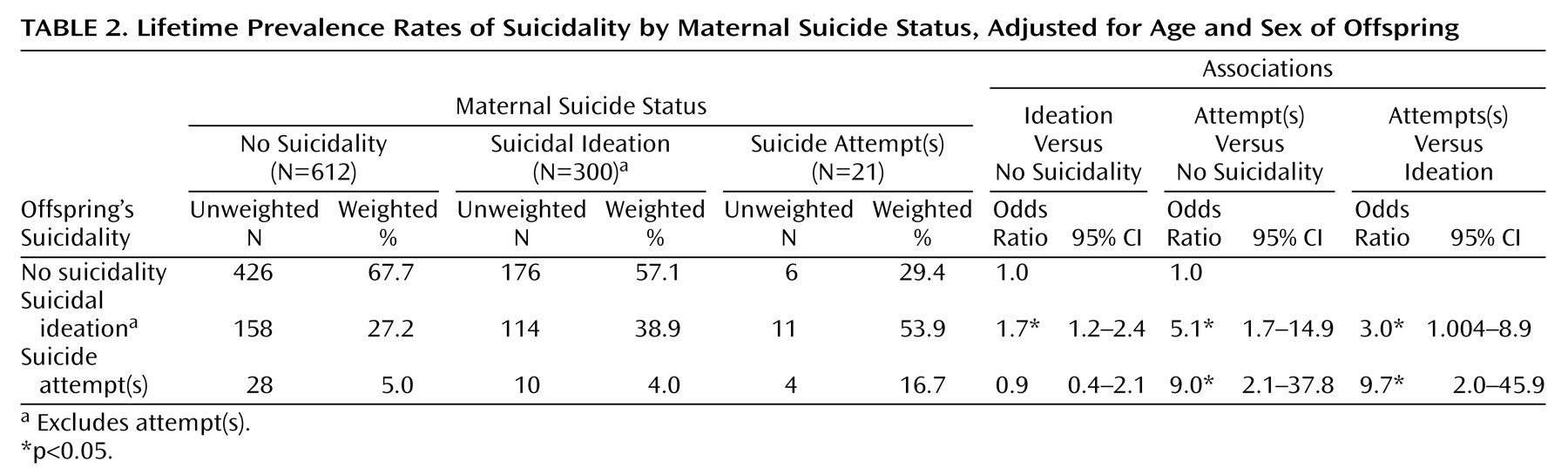

Logistic regression analyses revealed that the risk for suicidal ideation in the offspring was slightly increased if maternal suicidal ideation was present, whereas no association was found between maternal suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in their offspring (

Table 2). In contrast, stronger associations were obtained when we examined the associations between suicide attempts in the mothers and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the offspring. The odds for suicidal ideation was about five times higher, and the odds for suicide attempts was even nine times higher in the offspring of the mothers who had ever attempted suicide compared to the offspring of the mothers without any suicidality.

Significant differences in risk were found among the offspring of the mothers with suicidal ideation and the offspring of the mothers with suicide attempts, with a higher risk among the offspring of the mothers who reported suicide attempts.

Further analyses revealed that estimates remained relatively stable after we controlled for the mothers’ sociodemographic status. The odds for suicidal ideation in the offspring of the mothers with suicidal ideation, again, was only slightly elevated (odds ratio=1.6, 95% CI=1.1–2.9) and strongly elevated in the offspring of the mothers with suicide attempts (odds ratio=4.4, 95% CI=1.4–13.7) compared with the offspring of mothers without suicidality. The adjusted odds ratio for suicide attempts in the offspring of the mothers with suicidal ideation was 0.8 (95% CI=0.3–1.7), and in the offspring of the mothers with suicide attempts, it increased to 5.4 (95% CI=1.1–26.2).

Controlling for comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorders in the mothers yielded similar results, with the exception that the association between suicide attempts in the offspring and suicide attempt in the mothers remained only marginally significant, although the point estimate hardly changed (odds ratio=5.5, 95% CI=0.9–33.5, p=0.06).

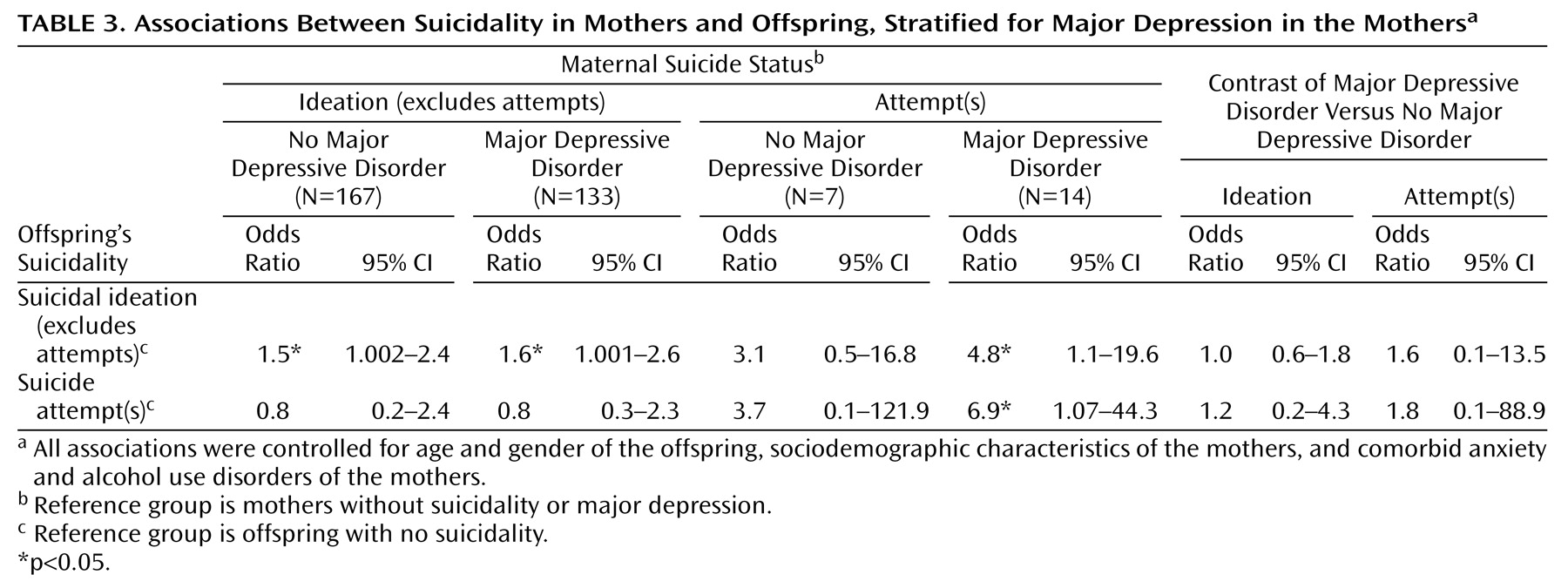

When we stratified maternal suicidal ideation and suicide attempts by maternal major depression status, no differences were found in the associations (

Table 3). In the case of suicide attempts, however, the confidence intervals were so broad that nearly nothing can be ruled out.

We expanded the analyses by splitting the category “suicidal thoughts” into those who endorsed the item for suicidal plans and those who did not. There were, however, only 22 offspring and 20 mothers (unweighted) who were classified into that category, and for the combination of mothers and offspring in that category, we found no single case. Therefore, we analyzed only associations between the maternal three-category variable (no suicidality, suicidal ideas only, and suicide attempt) and the offspring four-category variable (no suicidality, suicidal ideas without plans, suicidal ideas with plans, and suicide attempt) and vice versa. The results (available on request from the first author) for the differences between suicidal thoughts with and without suicidal plans revealed no clear and statistically stable pattern. No significant interactions were found for the offspring’s sex for all associations, suggesting similar odds ratios for female and male offspring.

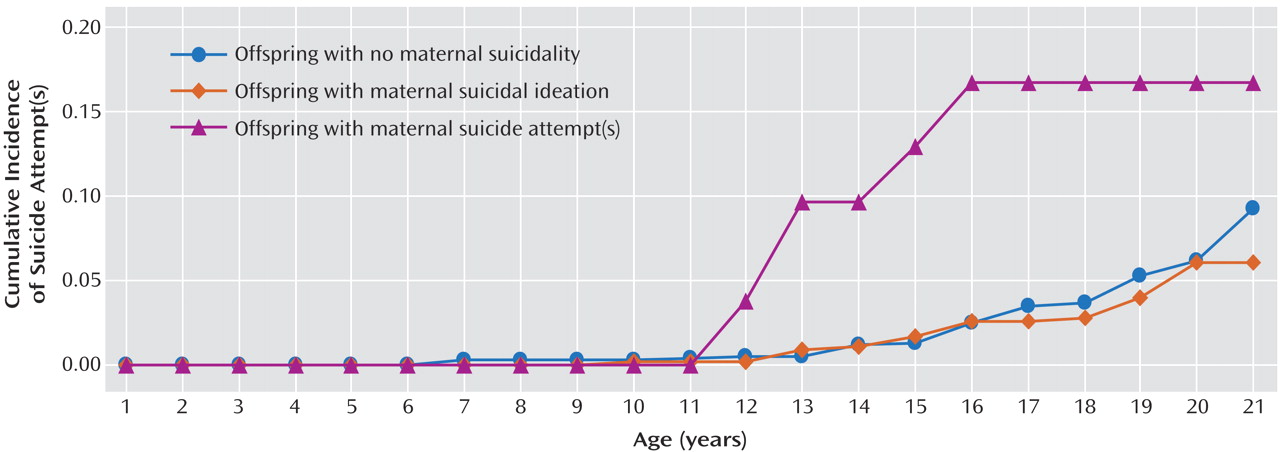

Maternal Suicidality and Age of Offspring’s First Suicide Attempt

Figure 1 shows the offspring’s age-specific probability for first suicide attempt by maternal suicidality status. There was a tendency toward the occurrence of a suicide attempt at an earlier age in the offspring of the mothers who attempted suicide compared to the offspring of mothers without suicidality (hazard ratio for interaction with age=0.6, 95% CI=0.3–1.0, p=0.06; hazard ratio for main effect with this model=4.8, 95% CI=1.1–20.6). No such finding was noted for the mothers who reported suicidal ideation (hazard ratio for interaction=0.9, 95% CI=0.6–1.3; hazard ratio for main effect with this model=0.9, 95% CI=0.4–1.9).

Discussion

The aim of this report was to extend our knowledge of the familial transmission of suicidality by exploring associations between maternal suicidality and suicidal behavior in their children. Notable features of the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology study are that 1) it is based on a representative community sample, 2) standardized symptom and diagnostic assessments of suicidal behavior were used, 3) independent diagnostic assessments of mothers and children were carried out, 4) suicidality outcomes in offspring were collected prospectively, and 5) the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology study was designed to collect data on a broad range of mental disorders in a representative sample of adolescents and not specifically on suicidality; thus, the questioning of suicidal behavior was embedded in the assessment of general psychopathology so that the threshold for the reporting of suicidal behavior was rather low.

Our study revealed two key findings. First, the risk for suicidal ideation, but not suicide attempts, was only slightly elevated in the presence of maternal suicidal ideation. By contrast, the risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the offspring was increased when maternal suicide attempts were present. These results are compatible with previous studies suggesting a familial aggregation of suicidality

(1,

6,

7,

13,

16,

25). Beyond this confirmation, our findings indicate that different familial associations might exist for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts and that the associations cannot be attributed to differences in the sociodemographic background of the mothers. Second, control for comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorders in the mothers yielded very similar results, suggesting that mother-offspring associations cannot be explained by maternal psychopathology associated with suicidality. Likewise, stratifying for major depression in the mothers did not reveal significant differences in associations. In confirmation with other studies

(5,

13,

16,

25), these results argue for the hypothesis that familial transmission of suicidality seems to be independent of other psychopathology. Genetic mechanisms may, in part, explain the observed associations, as suggested by twin and adoption studies

(16,

18–

20,

46). For example, Statham et al.

(16) demonstrated in a large community sample of monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs that genetic factors accounted for almost half of the variance concerning suicidal thoughts and behavior. It has also been discussed that familial clustering may be related to impulsiveness, aggressivity, or irritability in families directed inward or outward and stable over time and generations

(5,

6,

47). Such behavior seems to be strongly connected with a dysfunction of the serotonergic system

(48–

50). Currently, the genetic basis of this dysfunction is still unclear

(51). In addition, imitation or modeling could play an important role as an explanation for parent-to-child transmission

(52–

54). Imitation might also explain our finding that maternal suicidal ideation was not associated with suicidal behavior in offspring because suicidal thoughts are not observable, per se, by others. However, the results of studies addressing this issue directly do not support the imitation hypothesis as an explanation for familial transmission

(55).

Unlike most other studies, we additionally addressed gender-specific effects in the familial transmission of suicidality. Our findings suggest that familial risk acts similarly in males and females, confirming the findings of Qin et al.

(25).

It is noteworthy that we found some indications for suicide attempts occurring at an earlier age in the offspring of the mothers who attempted suicide compared to the offspring of the mothers without suicidality. There was no such finding when the mothers reported suicidal ideation only. Recently, Brent et al.

(7) reported a comparable effect specifically for the offspring of mood disorder probands. Despite the postulated continuum from suicidal ideation to suicide attempts

(56), this finding provided more support for a threshold model for explaining the development of suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults

(57).

The limitations of our study include the following. First, only mothers were interviewed for the assessment of suicidality in their respective families. The availability of information about suicidality in fathers would, however, probably have resulted in higher associations, provided that the elevated risks are not specific for mothers. Second, not all adolescents had passed through the entire risk period for the onset of suicidal behavior, probably also a source of underestimation. Third, these findings apply only to the subjects followed up to the age of 21. Fourth, the study focused on suicidal ideation and suicide attempts; the extent to which the results generalize to completed suicide remains to be explored. Finally, this report focused exclusively on maternal suicidality. Clearly, the manifestation of suicidality must be seen as a complex interplay of multiple factors

(12,

16,

18,

26), and maternal suicidality addresses only one of them. The investigation of the mechanisms through which maternal history of suicidality exerts its influence on offspring was beyond the scope of this report.

In conclusion, our study revealed that the offspring of mothers with suicide attempts are at a markedly increased risk for suicidality themselves. Furthermore, we found that maternal history of suicide attempts tended to predict an earlier onset of first suicide attempt in offspring. Our results provided no evidence against the hypothesis of suicidality running in families, independent of depression and other psychopathology.

Acknowledgment

This work is part of the Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology study and is funded by the German Ministry of Research and Technology (project numbers 01 EB 9405/6 and 01 EB 9901/6) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (LA 1148/1-1). The principal investigators are Dr. Hans-Ulrich Wittchen and Dr. Roselind Lieb. Current or former staff members of the group are Dr. Kirsten von Sydow, Dr. Gabriele Lachner, Dr. Axel Perkonigg, Dr. Peter Schuster, Dr. Franz Gander, Dipl.-Stat. Michael Höfler, and Dipl.-Psych. Holger Sonntag, as well as Mag. Phil. Esther Beloch, Dr. Martina Fuetsch, Dipl.-Psych. Elzbieta Garczynski, Dipl.-Psych. Alexandra Holly, Dr. Barbara Isensee, Dr. Marianne Mastaler, Dr. Christopher B. Nelson, Dipl.-Inf. Hildegard Pfister, Dr. Victoria Reed, Dipl.-Psych. Andrea Schreier, Dipl.-Psych. Dilek Türk, Dipl.-Psych. Antonia Vossen, Dr. Ursula Wunderlich, and Dr. Petra Zimmermann. Scientific advisers are Dr. Jules Angst (Zurich, Switzerland), Dr. Jürgen Margraf (Basel, Switzerland), Dr. Günther Esser (Potsdam, Germany), Dr. Kathleen Merikangas (NIMH, Bethesda, Md.), Dr. Ron Kessler (Harvard, Boston), and Dr. Jim van Os (Maastricht, the Netherlands).