Nonadherence to antipsychotic medication is quite common among schizophrenia patients and is the greatest obstacle to recovery and relapse prevention. This issue is heightened among individuals with a recent onset of schizophrenia who are just beginning to come to terms with having a psychiatric disorder and have not been in treatment long enough to recognize the necessity of adhering to their medication regimen (

1). Approximately 50% of patients discontinue antipsychotic medication or have significant nonadherence to their medication regimen within 1 year of beginning treatment, with rates rising to 75% within 2 years (

2). Some evidence indicates that nonadherence is greater in the early course of the disorder (

3). The clinical implications of nonadherence among first-episode patients are dramatic. Morken et al. (

4) demonstrated an odds ratio of 10.3 for psychotic relapse among nonadherent first-episode patients. In another study of first-episode schizophrenia patients, those who discontinued their medication had an almost fivefold increase in the risk for a first and second relapse (

5). Üçok et al. (

6) demonstrated that first-episode schizophrenia patients who experienced a psychotic relapse had a much higher rate of nonadherence (70%) than nonrelapsing patients (25%). Similarly, Chen et al. (

7) found that the 1-year relapse rates for adherent versus poorly adherent schizophrenia, schizoaffective, and schizophreniform patients were 18% versus 29%, respectively, and the 2-year relapse rates were 29% versus 42%, respectively. The cumulative relapse rate for first-episode patients with good adherence over a 3-year period was 36%, whereas the rate for poorly adherent patients was 57% (

7). Patients exhibit various levels of medication adherence behavior, often with partial or intermittent adherence, as opposed to complete nonadherence. Weiden et al. (

8) examined the effect of partial adherence, defined as taking a dosage that is consistently less than recommended, irregular dosing behavior, or having discrete gaps in antipsychotic therapy. They showed that gaps in medication use lead to relapse in chronic schizophrenia. Gaps as brief as 1–10 days were associated with a twofold increase in hospitalization risk (odds ratio=1.98), a gap of 11–30 days was associated with an odds ratio of 2.81, and a gap >30 days was associated with an odds ratio of 3.96. The authors also found that partial adherence increases the risk of hospitalization in the long-term treatment of chronic schizophrenia.

In addition to the personal suffering caused by psychotic relapse, medication nonadherence has a tremendous financial cost. Because as much as 50% of the direct medical costs of psychiatric hospitalization can be attributed to medication nonadherence, the cost of nonadherence is staggering (

9). Among mentally ill patients, nonadherence leads to increased hospitalization and concomitant hospital costs. In one study of patients with a severe and persistent mental disorder, those who used their medication irregularly had significantly higher rates of hospitalization than those who regularly complied with their medication treatment (42% versus 20%) as well as higher hospital costs ($3,992 versus $1,048) (

10). Hospital stays were also longer among nonadherent patients (mean=38.1 days [SD=20.4]) compared with patients who had been adherent prior to hospitalization (mean=14.3 days [SD=8.8]) (

11).

Assessment of medication adherence greatly varies among studies, with some assessment methods being more subjective and susceptible to inaccuracy than other methods. Nonetheless, the report of the patient, a subjective measure prone to an overestimation bias, is the most common method used to assess adherence (

12). Schizophrenia itself, or its neurocognitive concomitants, might impair a patient's ability to accurately report adherence behavior and lead to an inflated self-report of adherence (

13). To compensate for patient reporting errors, some have relied on collateral information from relatives, friends, and other treatment providers.

Reports to the clinician, or clinician observation, of the occurrence of medication side effects are another indirect indication that the patient is in compliance with some or all of the prescribed medication. Use of insurance reimbursement claims for medications is also a method for determining medication adherence that is more objective and easier to attain because it does not rely on the self-reports of the patient (

10). However, this method does not directly measure medication adherence behavior per se, since it assumes that patients who make insurance reimbursement claims have ingested all the drugs they received. Pill counts are assumed to be directly related to the number of pills ingested between counts but can be falsified by the patient to maintain an appearance of adherence (

14). Plasma and urine assays of the antipsychotic medication or one of its metabolites provide the strongest evidence of medication usage but are expensive and, in the case of blood tests, invasive. Furthermore, because of individual differences in the metabolism of medication, biological assays do not readily tell the clinician what dosage of medication the patient has taken.

As noted by Velligan et al. (

12), the definition of adherence varies greatly across studies and is often poorly operationalized. Differing definitions of adherence make it difficult to compare findings across studies. In many studies, adherence is merely defined as an all-or-nothing dichotomous variable, even though it is quite common for patients to exhibit partial adherence to their medication regimen (

15). Many studies have taken this into consideration and established a cutoff point for acceptable levels of adherence (

16). However, studies that have assessed partial adherence differ in the degree to which an individual can vary from the prescribed dosage and still be considered adherent (

12).

Longitudinal prospective studies are essential for determining the relationship between nonadherence and risk of relapse. There are few carefully controlled longitudinal studies examining nonadherence and the return of positive psychotic symptoms, especially for patients with a recent onset of schizophrenia. In the present longitudinal prospective study, we examined the effect of medication nonadherence on the return of positive symptoms in the initial phase of schizophrenia. We introduce a more comprehensive approach to the assessment of adherence and provide operational definitions of adherence that we hope will be widely adopted by others in the field. Similarly, psychotic symptoms were prospectively rated on a frequent basis, and systematic criteria were applied using an innovative computer scoring program to identify periods in which psychotic symptoms returned. In addition, we used a statistical methodology that is well suited for examining medication nonadherence because it allows for multiple at-risk periods of nonadherence and multiple occurrences of symptom return per participant during the follow-up period.

Method

Participants

The study sample consisted of 49 individuals who were recruited from a variety of local Los Angeles-area psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric clinics and through referrals from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), outpatient service at the Resnick Neuro-psychiatric Hospital. These participants were not recruited or referred to us based on their levels of previous medication adherence. All study participants were receiving outpatient psychiatric treatment at the UCLA Aftercare Research Program and were participants in the third phase of the Developmental Processes in Schizophrenic Disorders Project (principal investigator: Dr. Nuechterlein) (

17). Typically, the outpatient psychiatric treatment involved clinic visits 1 day per week, in which the various interventions described in this article were provided. The Aftercare Research Program was the participants' primary source of mental health care. The present study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board. All participants were provided with oral and written information about the research procedures involved in the study and gave written informed consent.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Entry criteria were as follows: 1) a recent onset of psychotic illness, with the beginning of the first major psychotic episode occurring within the last 2 years; 2) a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, mainly schizophrenia type, according to Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (

18); 3) at least 18 but not >45 years of age; 4) no evidence of a known neurological disorder; 5) no evidence of significant and habitual drug abuse or alcoholism in the 6 months prior to hospitalization, no evidence that the psychosis was accounted for by substance abuse, and no evidence that substance abuse would be a prominent factor in the course of illness; 6) no premorbid mental retardation; 7) sufficient acculturation and fluency in the English language to avoid invalidating research measures of thought, language, speech disorder, verbal abilities, and attitudes toward psychiatric treatment; 8) residence within commuting distance of the UCLA Aftercare Program; 9) interest in trying to resume work or school; and 10) no contraindication for treatment with risperidone, given that this was the initial standardized antipsychotic medication used in the study.

As assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (

19) and informant information, the distribution of entry RDC diagnoses consisted of schizophrenia (81.6%); schizoaffective disorder, depressive type, mainly schizophrenia (16.3%); and schizoaffective disorder, manic type, mainly schizophrenia (2.0%). The DSM-IV diagnosis distribution involved schizophrenia (63.3%); schizophreniform disorder (18.4%); schizoaffective disorder, depressive type (14.3%); schizoaffective disorder, manic type (2.0%); and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (2.0%). The mean patient age at study entry was 24.2 years (SD=4.0); the mean educational level was 13.5 years (SD=2.0); and 65% of participants were men. In addition, the mean parental educational level was 14.9 years (SD=3.6). Thus, the participants had an age level, educational achievement level, and gender distribution that is typical of individuals with a first episode of psychosis. The racial background among participants, similar to that of the Los Angeles metropolitan region, was as follows: Caucasian (39%), Hispanic (13%), Asian (13%), African American (23%), and other/mixed (12%). At study entry, the sample had a mean illness duration of 10.8 months (SD=13.5) since the onset of the first psychotic symptoms lasting ≥1 week. The expanded 24-item version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (

20) was used to monitor symptom severity, with each item rated from 1 (not present) to 7. At the time of the entry diagnostic assessment, the participants were usually psychotic and many had negative symptoms. At the outpatient stabilization point, which was the beginning of the 18-month follow-up period, the mean score on items for the BPRS thought disturbance factor (unusual thought content, hallucinations, and conceptual disorganization) (

21) was only 1.9 (SD=1.1). The mean score on items for the withdrawal-retardation factor (blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, and motor retardation) was 2.3 (SD=1.1). During the most recent hospitalization that preceded study entry, approximately 48% of patients had received treatment with risperidone, 15% had received treatment with another second-generation antipsychotic (primarily olanzapine), and 21% received treatment with a first-generation antipsychotic, with some overlap among these treatments. The typical length of previous antipsychotic treatment was 4 weeks. Prior to the most recent hospitalization, the majority of patients had not received treatment with antipsychotic medication. Adherence to antipsychotic medication during the inpatient psychiatric hospitalization preceding study entry was typically quite good. Somewhat lower levels of adherence occurred during the outpatient clinical stabilization period leading up to our baseline starting point for the longitudinal protocol. Only participants with at least 6 months of follow-up data were included in this study. The average length of follow-up assessment was 13.1 months (SD=6.1), with 39% of the sample completing at least 17 months of follow-up evaluation. Nine participants who dropped out did so without accepting treatment elsewhere.

In this 18-month, longitudinal protocol called Improving and Predicting Work Outcome in Recent-Onset Schizophrenia (

17), all participants were provided treatment with antipsychotic medication, regular psychiatrist visits, and individual case management and therapy by master's- and doctoral-level therapists. The second-generation antipsychotic medication, risperidone, was used as the first-line medication to standardize initial treatment conditions, and thus the effects of two psychosocial approaches to improving work outcomes could be more clearly evaluated. (If an inadequate response to risperidone or intolerable side effects were observed, study psychiatrists then prescribed a different second-generation antipsychotic medication.) An initial 2- to 3-month period was used for outpatient clinical stabilization on antipsychotic medication. The mean dosage of oral risperidone at the study baseline point was 4.2 mg/day (SD=1.8). The participants were then randomly assigned to either an Individual Placement and Support (

22) and Workplace Fundamentals Module (

23) intervention condition or a Brokered Vocational Rehabilitation condition (vocational rehabilitation through referral to traditional outside agencies), in a two-thirds versus one-third ratio. The details of the psychosocial intervention protocol have been described elsewhere (

17). In the present study, we focus on those aspects relevant to medication adherence and clinical outcomes.

We examined the period beginning at the outpatient stabilization point until the end of the 18-month protocol or until the patient with-drew from treatment or was switched to an antipsychotic medication other than risperidone

Nonadherence

All sources of information, listed in

Table 1, were considered in categorizing medication adherence. Typically, patient self-report and clinician judgments were available at each rating point, pill counts were available every 1–2 weeks, and plasma levels were assayed every 4 weeks. The first step in categorizing medication adherence was to create a rating of the degree of medication adherence (

Table 2) for each week of follow-up assessment, based on the sources of information. Weekly adherence ratings were conducted even when all sources of information were not available during a given rating period.

We then identified periods of nonadherence that met specific operational definitions involving the severity and duration of nonadherence over periods of ≥2 contiguous weeks. Our operational definitions of mild, moderate, and severe nonadherence are presented in

Table 3. This adherence categorization system builds on our previous investigation (

24) as well as that of Donohoe et al. (

25).

Psychotic Exacerbation/Relapse

Psychiatric symptoms were assessed every 2 weeks using the expanded BPRS (

20). This expanded version has 24 items that meas-ure psychiatric symptom severity and has been shown to have high interrater reliability. The 18-month follow-up BPRS interviews were evaluated using a computer program (

26) to identify the following three types of positive psychotic symptom return: remission followed by relapse, remission followed by significant exacerbation, and persisting symptoms followed by significant exacerbation (for further details, see the table in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article). Our modification of the scoring program, described by Nuechterlein et al. (

26), allowed for multiple occurrences of psychotic symptom return for each patient.

Data and Statistical Analyses

Proportional hazards regression (SAS PHREG, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C.) with the sandwich estimator of the variance (

27) was used to determine whether medication nonadherence was associated with an increased risk of psychotic symptom return. The robust sandwich estimator of the variance was used because the outcome event (i.e., psychotic relapse or exacerbation) could occur more than one time per participant.

Results

First we examined the number of periods of nonadherence, according to the three main definitions, in this recent-onset schizophrenia sample (

Table 3). A period of mild nonadherence was common (33% of patients). Moderate (16%) and severe (19%) nonadherence were relatively less common. Thirty-two percent of patients did not have a period of nonad-herence according to the criteria.

Next we tallied the number of periods in which psychotic symptoms returned. Thirteen out of the 49 patients (27%) had a return of psychotic symptoms meeting exacerbation/relapse criteria a total of 23 times during the follow-up period (six patients met criteria more than once).

We examined the effect of a brief period of mild nonadherence on return of psychotic symptoms. This analysis focused on the consequences of compliance with only 50%–75% of the prescribed medication for ≥2 consecutive weeks. The hazard ratio for these brief periods of nonadherence was 5.8 (95% confidence interval [CI]=1.1–29.8; χ2=4.5, df=1, p<0.04 [N=32]). The effect of moderate nonadherence was even more striking (hazard ratio=28.5, 95% CI=1.8–455.7; χ2=5.6, df=1, p<0.02 [N=40]), which lends additional support to the view that even partial medication nonadherence has deleterious effects. Severe nonadherence also significantly predicted return of psychotic symptoms, with a hazard ratio of 3.7 (95% CI=1.4–9.5; χ2=6.6, df=1, p<0.02 [N=49]). These hazard ratios did not statistically differ from each other. Therefore, we cannot conclude that mild or moderate periods of nonadherence put patients at significantly greater risk than severe nonadherence.

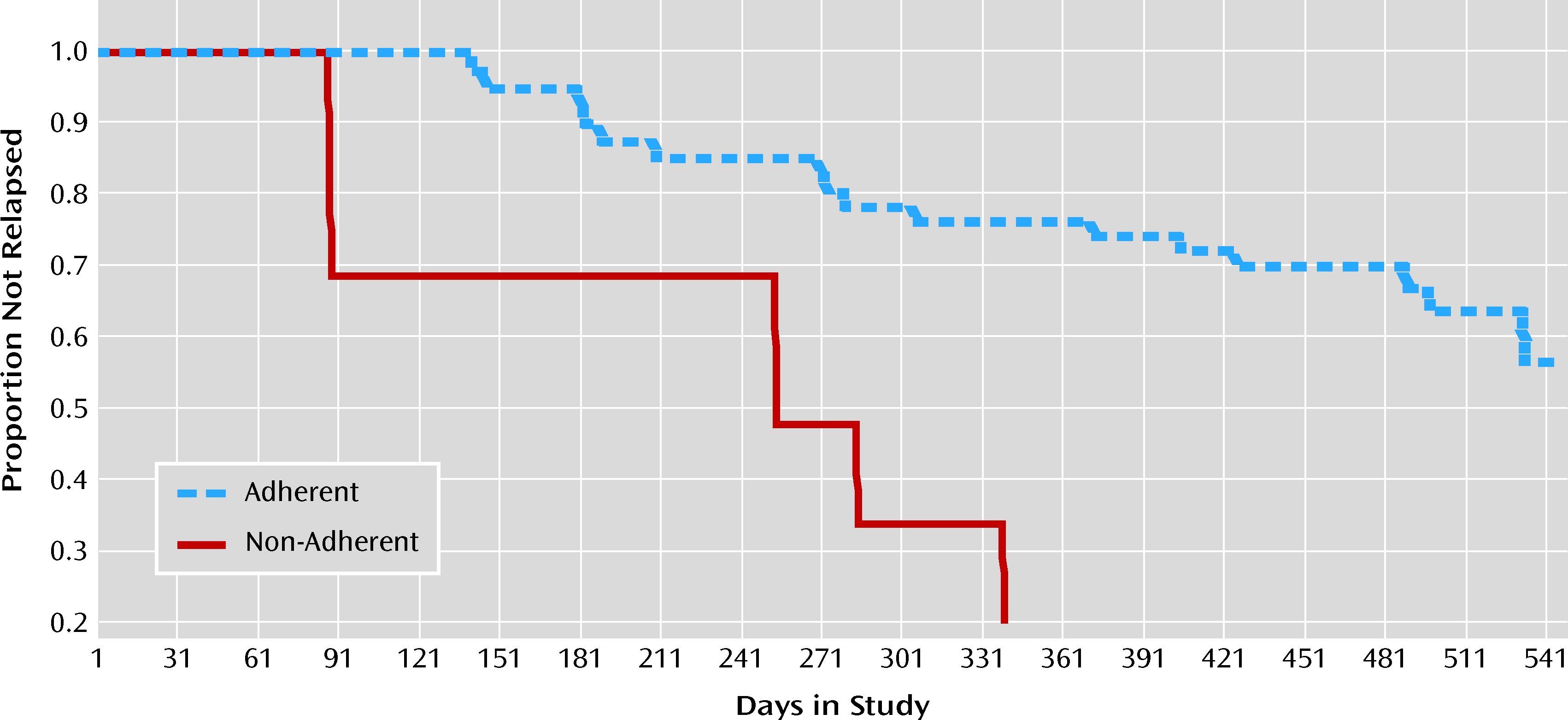

We also examined alternative definitions of nonadherence that are commonly observed in clinical practice. Any period of mild or greater severity nonadherence was significantly predictive of return of psychotic symptoms (hazard ratio=3.4, 95% CI=1.4–8.1; χ

2=10.3, df=1, p<0.002 [N=49]). Similarly, any period of moderate or greater nonadherence was significantly predictive of return of psychotic symptoms (hazard ratio=4.2, 95% CI=1.7–10.4; χ

2=8.8, df=1, p<0.004 [N=49]). Further clinical exploration of the moderate or greater nonadherence category showed that 17 patients had 22 periods of nonadherence. The mean time of nonadherence was 2 months (mean=64 days [SD=83]) per nonadherence episode. For nonadherent patients, the first episode of moderate or greater nonadherence typically began 6 months (mean=183 days [SD=166]) after outpatient stabilization. For patients who had a return of psychotic symptoms during medication nonadherence, the mean time from the beginning of nonadherence until relapse was approximately 2½ months (mean=72 days [SD=53]).

Figure 1 shows the proportion of patients who did not experience psychotic exacerbation or relapse as a function of time, according to whether or not they had a period of moderate or greater nonadherence.

Discussion

We found that periods of partial adherence (50%–75% of prescribed dosage) and relatively brief periods of partial or full nonadherence (2–4 weeks) with oral antipsychotic medication put schizophrenia patients at significant risk of psychotic exacerbation or relapse during the early course of their illness. This study refined the methods of evaluating medication nonadherence in several ways to examine more rigorously the effect of brief, partial medication nonadherence on symptom return among recent-onset schizophrenia patients. First, we collected data of several types (patient reports, clinician assessments, pill counts, and plasma assays). Second, we used these data to make weekly best-estimate ratings of adherence. Third, we then categorized the medication compliance behavior of participants, throughout the follow-up period, into different degrees of nonadherence according to operational definitions. We offer these graduated sets of operational definitions of adherence in order to help standardize the operational definitions of medication adherence in the field and to allow easier comparison of findings across studies. In addition, frequent, prospective symptom ratings with a well-validated semistructured interview and verbally anchored rating scale were employed to detect exacerbation or relapse. An objective definition of exacerbation/relapse was applied through a computer scoring program (available upon request from Nuechterlein et al. [

26]), modified to identify multiple recurrences of positive symptom exacerbation or relapse. Finally, we used a form of survival analysis that is appropriate for data involving both risk periods and outcomes (i.e., psychotic exacerbation or relapse) that can reoccur during follow-up assessment.

Our finding that brief periods of oral medication nonadherence led to a return of psychosis is consistent with the previous literature on first-episode schizophrenia (

4–7,

28). The present study extended these findings to the early phases of schizophrenia by using well-operationalized definitions of nonadherence that quantified three levels of partial nonadherence. It is noteworthy that even small deviations from the prescribed medication regimen had a strong effect on symptom return. Brief (2-week) interruptions in antipsychotic medication usage were highly problematic and strongly related to risk of psychotic exacerbation or relapse. Clearly, a substantial subset of patients cannot tolerate even this brief period of nonadherence. Because the differences among these risk ratios were not statistically significant, it cannot be concluded that mild or moderate nonadherence is inherently more risky than severe nonadherence. The patients who were not able to withstand mild or moderate nonadherence would likely have also relapsed if their nonadherence had been more severe. These patients, however, relapsed quickly during lower-level nonadherence and did not reach the duration that would be considered severe nonadherence. In contrast, there are some patients who can sustain longer periods of severe nonadherence.

It is possible that the nonadherence among these especially vulnerable patients was part of an undetected, albeit brewing, storm of impending subclinical symptomatic and psychophysiological changes (

29), which contributed to the strikingly hazardous effects of brief periods of partial nonadherence. Even missing as little as 25% of the prescribed dosage over a period of ≥2 weeks significantly raised the risk of psychotic symptom return. Our findings, together with those of Weiden et al. (

8), make it clearer that there is very little leeway for brief gaps in oral antipsychotic medication usage or dosage reductions. It is not clear whether our awareness of this lack of tolerance for variations in medication compliance is simply increasing over time or whether the current clinical practice of prescribing the lowest amount of psychiatric medication to ameliorate symptoms while keeping side effects at a minimum might be contributing to a situation in which there is very little allowance for even partial nonadherence.

The heightened risk of relapse with medication nonadherence in the present study was for patients who had reduced or discontinued their antipsychotic medication against medical advice and is comparable to a common clinical situation in out-patient treatment. In this sample, moderate or greater nonadherence typically began approximately 6 months after clinical stabilization, and return of psychotic symptoms began an average of a little more than 2 months after nonadherence started. Thus, clinicians might be particularly watchful and discuss patients' attitudes toward their medications during this period. Patients who reduce or stop their medication against medical advice might be at greater risk of relapse while they are nonadherent than clinically stable patients who are trying to taper their medication in close collaboration with their treating psychiatrists. Patients who stop medications against medical advice often lack insight into their need for medication, further complicating their treatment. A further consideration is that patients with a less than optimal response to an antipsychotic medication might be more likely to become nonadherent and subsequently be more susceptible to a return of positive symptoms than patients who have a better treatment response. A more fine-grained temporal analysis of the interplay of changes in symptoms, insight, and medication adherence will be necessary to disentangle these effects and will be the subject of future studies.

Clinicians were hopeful that the emergence of second-generation antipsychotic medications would herald an era of greater antipsychotic medication acceptance and adherence. However, despite advances in side effect profiles, nonadherence with second-generation antipsychotic medications continues to be a major clinical problem. To more fully understand the causes of medication nonadherence and to develop improved treatments, we need to understand better the factors that serve as barriers to medication adherence (

15,

30). Furthermore, given the clear association between continued antipsychotic medication and psychotic symptom control, nonadherence to antipsychotic medication should be more regularly considered when examining correlates of clinical outcome in schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients for their participation in this longitudinal study. The authors acknowledge the assistance of the caring UCLA Aftercare Research Program case managers: -Kimberly Baldwin, M.F.T.; Rosemary Collier, M.A.; Sally Friedlob, M.S.W.; Deborah Gioia, Ph.D.; Tasha Nienow, Ph.D.; and Luana Turner, Psy.D., as well as treating psychiatrists Martha Love, M.D., and Benjamin Siegel, M.D., and the medication adherence raters, Miriam Barillas, B.A.; Liset Crespin, M.A.; and Rebecca Gordon, B.A. The authors also thank Manickam Aravagiri, Ph.D., for supervising the risperidone plasma assays.