Elevated rates of cannabis use have repeatedly been observed among individuals with schizophrenia. A recent review of 53 treatment studies found that the average 12-month prevalence of cannabis use was 29.2% among patients with psychosis (

1), compared with 4.0% in the general U.S. population (

2). Furthermore, prospective studies indicate that cannabis use is associated with a twofold increase in the odds of developing schizophrenia and related disorders (

3–

6), and retrospective studies have suggested that cannabis use may hasten the onset of schizophrenia (

7,

8). These findings are typically interpreted as evidence that cannabis plays an etiologic role in psychosis, although the precise mechanism remains unknown (

9). One review of the existing evidence (

10) concluded that cannabis is unlikely to cause permanent neurological changes associated with schizophrenia, although the transient neurochemical effects of this substance may be particularly adverse among individuals with a genetic vulnerability to psychosis.

While the role of cannabis exposure in the onset of psychosis has received much attention, relatively few systematic studies have been conducted on the impact of continued cannabis use on the course of schizophrenia. Some individuals with schizophrenia report using cannabis to relieve symptoms or medication side effects (

11). Also, some cross-sectional studies have reported that cannabis use is associated with less severe negative and disorganized symptoms (

12).

On the other hand, other cross-sectional data indicate that cannabis users have more severe psychotic symptoms than nonusers (

13,

14). Furthermore, a recent review (

15) of 13 longitudinal studies concluded that cannabis use is associated with increased rates of relapse but that the links with specific symptoms were less consistent. For example, two longitudinal studies of cannabis abuse in schizophrenia yielded conflicting findings: one reported an association with severity of thought disorder but not psychotic or negative symptoms (

16), and the other reported an association with severity of negative symptoms but not disorganized or psychotic symptoms (

17). Zammit and colleagues (

15) noted that these inconsistencies across studies can be explained in part by methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes and lack of control for initial symptom severity and other confounders.

Despite these mixed findings, there is emerging evidence from two recent studies that patients with psychotic disorders may experience symptom exacerbation even from mild cannabis exposure. For example, Grech and colleagues (

18) found that individuals with recent-onset psychosis who consistently used cannabis had more severe psychotic and disorganized symptoms than nonusers even after adjustment for age, gender, and ethnicity. Examining symptom severity globally rather than within specific domains, Degenhardt and colleagues (

19) found a small but significant linear relationship between number of days using cannabis in the past month and severity of subsequent psychiatric symptoms across a 1-year follow-up, even after controlling for demographic variables and initial symptom severity. Together, these studies suggest that even minor cannabis use may be associated with worse outcomes. However, it remains unclear what aspects of the course of schizophrenia are affected.

In addition to schizophrenia symptoms, there is evidence to suggest that cannabis use is associated with depression and level of functioning. A link between heavy cannabis use and depression has been observed in the general population (

20). This has not been well studied in schizophrenia, although one report found no relationship between cannabis use and depressive symptoms (

19). Furthermore, some studies suggested that cannabis use is more likely to occur among better-functioning patients (

13,

19) despite its association with greater symptom severity. For instance, a cross-sectional study found schizophrenia patients with comorbid cannabis abuse to have better premorbid adjustment (

21).

In sum, there is accumulating evidence that cannabis use may worsen the course of schizophrenia, but it is unclear what is driving this effect; many previous studies did not control for initial symptom severity and examined general illness severity rather than specific symptoms. Our goal in this study was to address these limitations by identifying specific characteristics of schizophrenia associated with cannabis use during the 10 years following first admission for psychosis and to investigate the direction of these associations. The primary strengths of this study are a relatively large sample size, comprehensive assessment of clinical course, and a long follow-up with multiple assessment points.

Method

Participants

Data were obtained from the 229 individuals with DSM-IV research consensus diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophreniform disorder participating in the Suffolk County Mental Health Project (

22). A total of 675 participants were recruited from the inpatient units of the 12 psychiatric facilities in Suffolk County, N.Y., between 1989 and 1995. The inclusion criteria were age 15–60 years, first admission either concurrent or during the previous 6 months, clinical evidence of psychosis, ability to understand the assessment procedures in English, and capacity to provide written informed consent. After the baseline assessment (for which the response rate was 72%), face-to-face interviews were performed 6 months and 2, 4, and 10 years later. The interviews included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R and, later, DSM-IV (SCID;

23), administered by trained master's-level mental health professionals. Baseline interviews assessed current and lifetime conditions, and follow-up interviews included current and interval ratings. The 229 respondents who are the focus of this study received a longitudinal consensus DSM-IV diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder after the 2-year follow-up assessment (

24). These diagnoses were formulated by a team of four or more psychiatrists using all available information from interviews, medical records, and significant others.

The procedures for obtaining informed consent were approved annually by the Committees on Research Involving Human Subjects at Stony Brook University and by the institutional review boards of all hospitals where respondents were recruited. After receiving a complete description of the study, patients provided written informed consent; for participants under age 18, written consent from parents was also obtained.

The cross-sectional analyses of cannabis use were based on all available respondents at each time point. As noted, there were 229 participants at baseline. At 10 years, 162 participants provided complete data, 25 provided partial data, 10 declined to participate, 19 were untraceable, and 13 had died. The 162 for whom complete information was available were similar to the remaining 67 participants on all variables in this study.

Measures

Cannabis use and age at first use were assessed as part of the substance use disorders module of the SCID and items modeled on the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse interview (

25). Participants were asked about their cannabis use in the past 30 days at baseline and at 10 years and about their use in the previous 6 months at the 6-month, 2-year, and 4-year follow-ups. Cannabis use was dichotomized to reflect use at least once in the specified time frame or no use during that time frame. Frequency of use and percent with lifetime DSM-III-R abuse or dependence (determined by the SCID) were also examined in relation to use. The lifetime data were collected before publication of DSM-IV, but diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders in DSM-III-R and DSM-IV are similar.

Symptoms of psychosis in the month preceding each interview were measured with the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS;

26) and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS;

27,

28). The SANS taps affective blunting, alogia, avolition, anhedonia/asociality, and inattention, and the SAPS measures psychotic symptoms (hallucinations and delusions) and disorganized symptoms (bizarre behavior and thought disorder). Factor analysis indicated that in this sample the SANS can be best scored as a single overall index and the SAPS as two subscales: psychotic and disorganized (

29). Age at onset of psychosis was based on a timeline for each psychotic symptom assessed by the SCID, along with information from medical records and informants (

30).

Symptoms of depression in the month preceding interview were assessed with the SCID depression module, administered without skipouts. The nine DSM-IV criterion symptoms were rated as 1=not present, 2=questionable, and 3=definite. Depression was operationalized as a composite of these nine criterion symptoms.

Illness severity was operationalized as interviewers' (baseline) and psychiatrists' (follow-up) consensus Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) rating for the worst week in the past month.

Five background variables were included: sex, age at baseline, parental socioeconomic status (of the parent with the higher occupational level), presence or absence of other drug use (stimulants, cocaine, and so on, assessed in parallel with cannabis use), and presence or absence of antipsychotic medication use in the past month.

Data Analysis

Proportional hazards regression was used to examine the association between first cannabis use (modeled as a time-varying covariate) and the onset of first psychotic symptoms, with adjustment for gender, age cohort, and socioeconomic status at baseline. The stability of cannabis status was evaluated with tetrachoric correlations. Cross-sectional comparisons of users and nonusers were made with multiple linear regression. Longitudinal correlates of cannabis use (no/yes) were examined using a mixed-effects logistic regression model (

31). These within-person analyses tested which variables were associated with the starting or stopping of cannabis use for the patient over time. The independent variables included time-varying clinical covariates (SAPS, SANS, and depression scores; other drug use; and antipsychotic medications) and demographic characteristics (age, sex, and socioeconomic status). GAF score was analyzed separately. These models had a fixed term for time (measured in years) and a random intercept term, which allows the estimation of a separate trajectory for each individual. All variables except time were standardized with respect to their grand means and standard deviations (across all subjects and waves) to facilitate interpretation. In this analysis, the random-effects covariance structure was specified as an unstructured covariance matrix, as it imposed the fewest constraints and provided a better fit than all other covariance matrices.

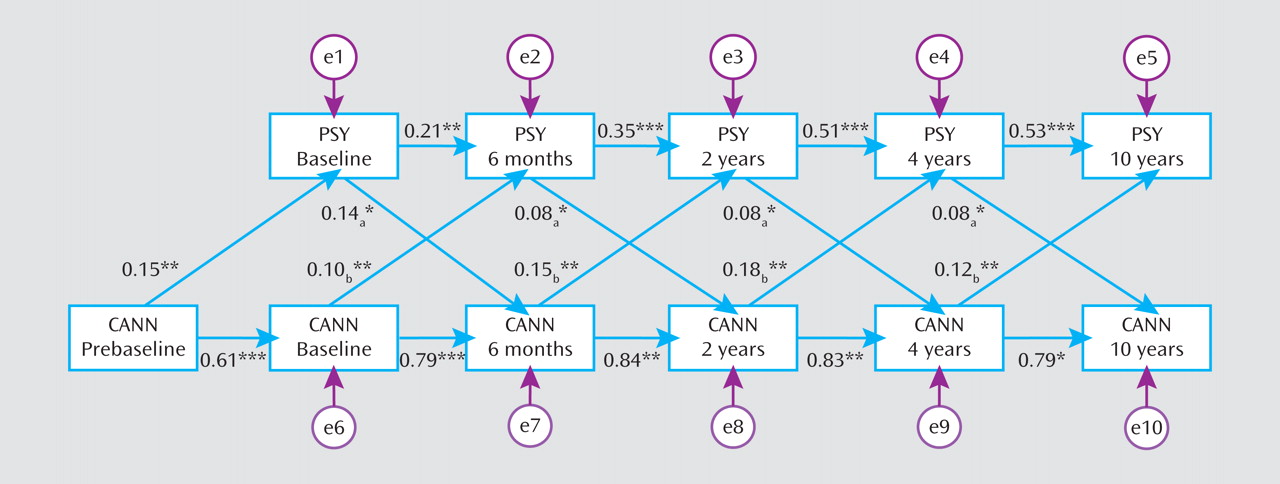

For variables that covaried with changes in cannabis use over time, we also evaluated the direction of the association using structural equation modeling. We specified a cross-lagged model, in which each follow-up variable was predicted jointly by cannabis use and symptom levels from the preceding wave. Thus, the model assumes contributions of symptoms to future cannabis use above and beyond past cannabis use, and vice versa. We constrained equivalent paths to be equal, namely, paths from the symptom variable to cannabis use at each wave and from cannabis use to the symptom variable at each wave. The change in chi-square from the unconstrained to the constrained model was not statistically significant. The model also included cannabis exposure prior to baseline, which predicted both baseline variables. Structural equation modeling was performed using Mplus version 5.1. In evaluating the model, we considered two fit indices, the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Conventional guidelines suggest that CFI values ≥0.90 indicate an adequate fit, and values ≥0.95 indicate an excellent fit; RMSEA values ≤0.10 indicate an adequate fit, and values ≤0.06 indicate an excellent fit (

32).

Missing data were addressed in structural equation modeling using the full information maximum likelihood method (

33), which estimates models from all available data, thus minimizing attrition-related biases (

34). An analogous approach was employed in mixed-effects logistic regression, so that data from each participant were included in the analysis. Thus, the longitudinal analyses were based on 880 observations.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics

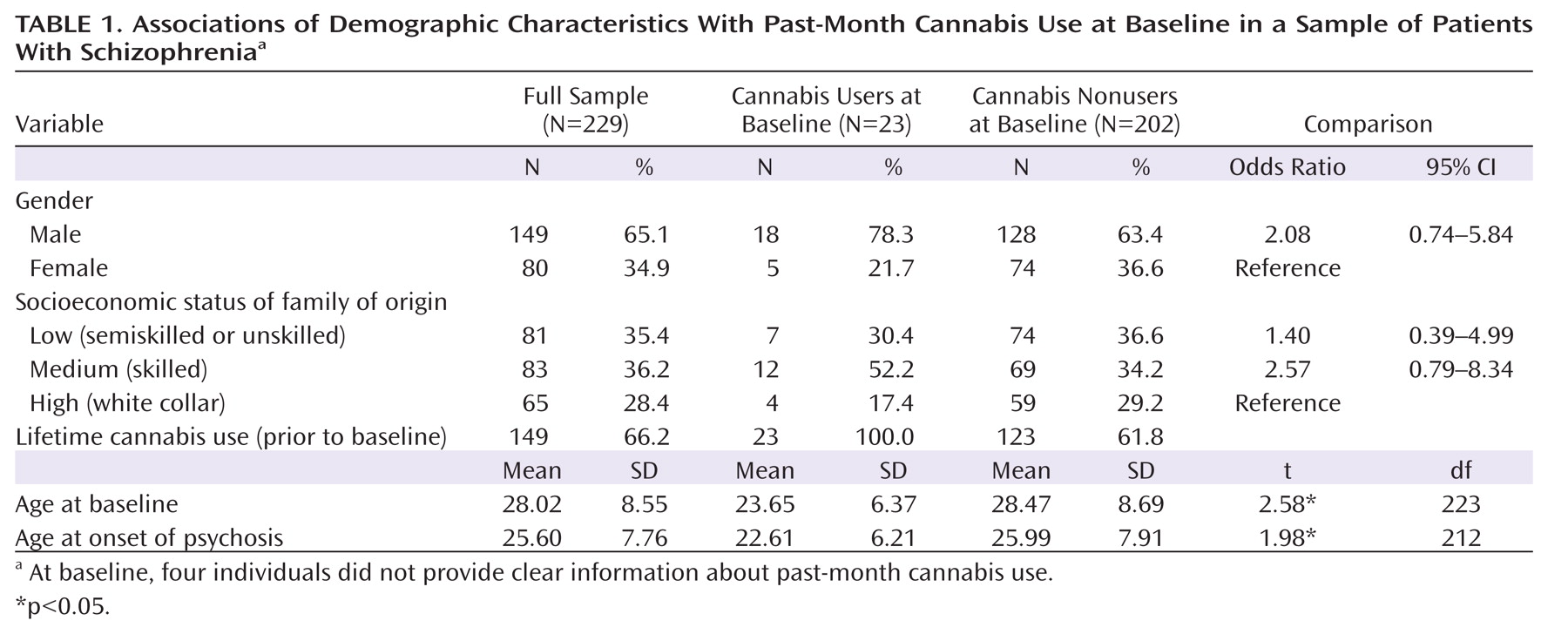

The characteristics of the sample and comparison of baseline users and nonusers of cannabis are presented in

Table 1. At baseline, the lifetime use rate was 66.2%. Sixty-four lifetime users (43.0%) met DSM-III-R criteria for abuse or dependence. On average, current cannabis users were younger at first admission and had an earlier age at onset of psychotic symptoms. Although the differences in gender and socioeconomic status were nonsignificant, cannabis use was more common among males and among participants from families of low and medium socioeconomic status.

Consistent with prior studies, survival analysis showed that among users, the risk of psychosis onset in any given year following exposure to cannabis doubled compared to the risk among same-age nonusers (hazard ratio=1.97, 95% CI=1.48–2.62, p<0.001). Inspection of patterns of cannabis use among age cohorts revealed that cannabis use was more prevalent and started at an earlier age among participants who were younger than age 35 at baseline (data not shown). This cutoff is consistent with the normalization of cannabis use in the 1960s and 1970s (

35). After adjusting for age cohort (baseline age <35 versus ≥35), gender, and socioeconomic status, the association of cannabis use with age at onset of psychosis remained significant (hazard ratio=1.34, 95% CI=1.01–1.77, p<0.05).

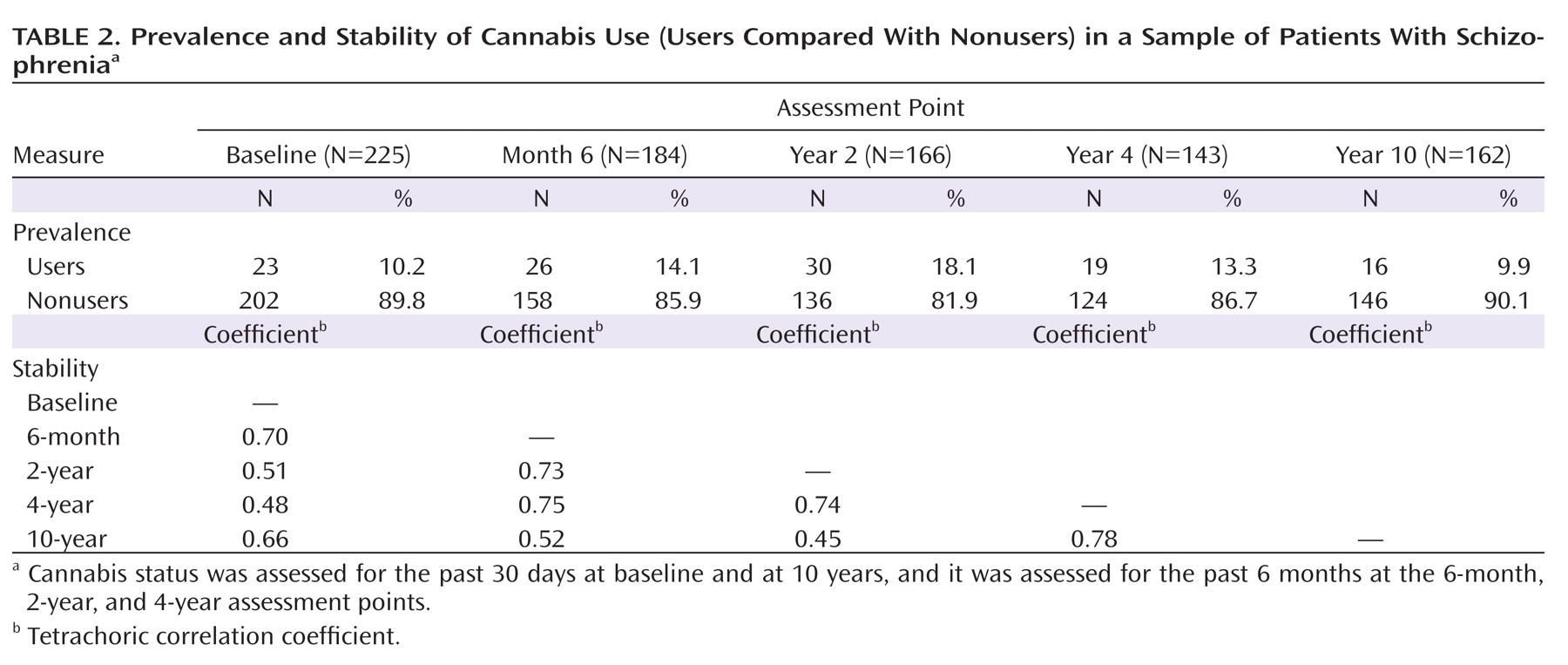

Prevalence and Stability of Cannabis Use

At baseline and 10 years, the 1-month rates of use were both around 10%, and the 6-month rates obtained during the other follow-up intervals ranged from 13% to 18% (

Table 2). The average frequency of use was 9.0 days per month (averaging 1.3 joints per day of use).

Cannabis status showed substantial stability over the 10-year follow-up period, with correlations among waves ranging from 0.48 to 0.78 (Table 2). Although patterns of cannabis use tended to persist, a fair number of individuals stopped or started over the course of the follow-up period. In fact, of the 62 individuals who were using at any of the waves, only seven were using cannabis at each available time point. Six of them had a history of cannabis abuse or dependence. We also compared users and nonusers with regard to the presence or absence of antipsychotic medication use but found no differences at any of the five assessment points.

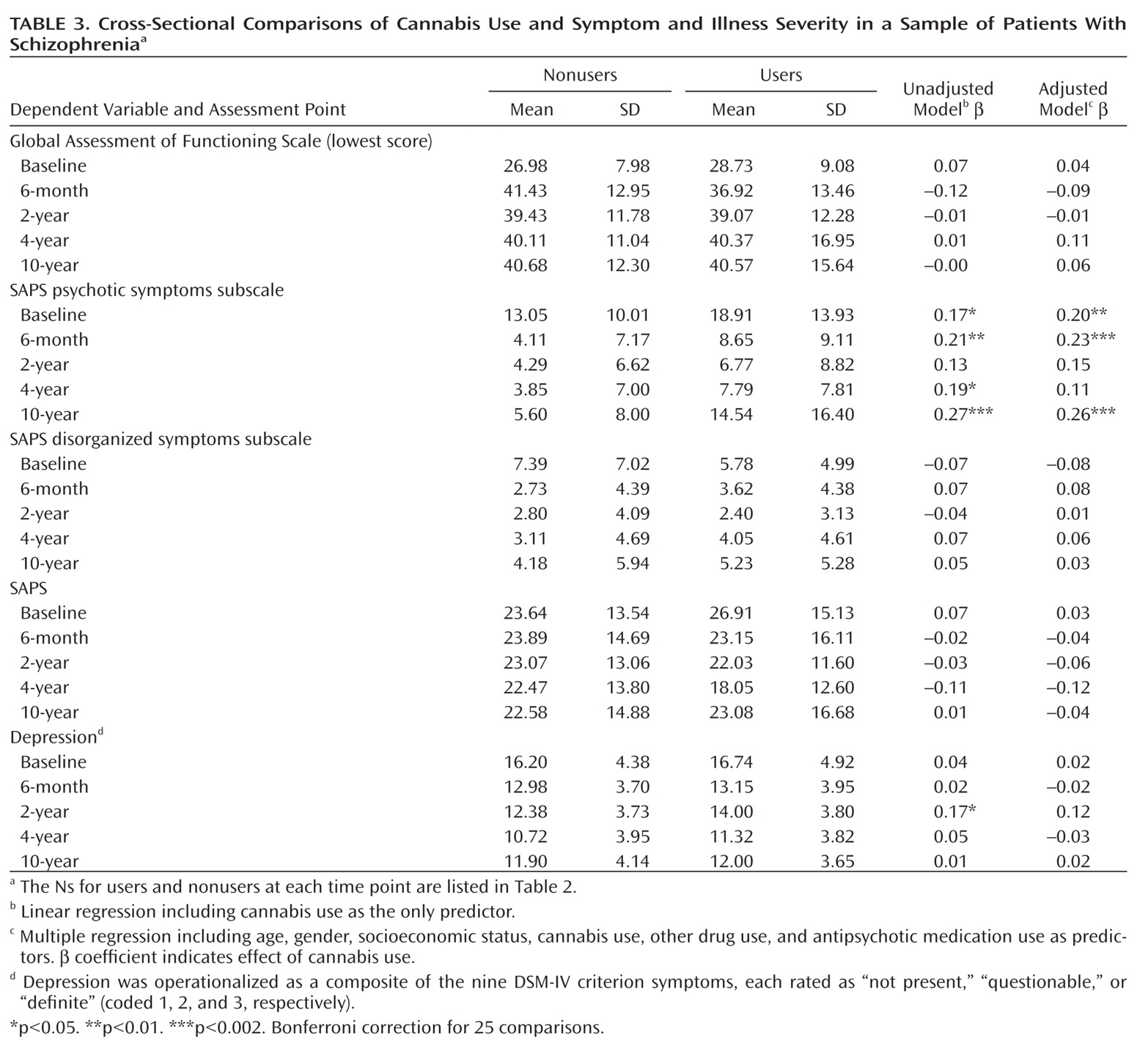

Cross-Sectional Comparisons of Cannabis Use and Symptom Severity

Cannabis users had elevated levels of psychotic symptoms at four of the five assessment points, with an average β coefficient of 0.19 (unadjusted model;

Table 3). The only other significant difference was greater depression severity in users at year 2. After adjustment for covariates, the difference in psychotic symptoms was significant at three time points, and two after Bonferroni correction; the average β coefficient was unchanged at 0.19. For participants using at least three times per month, the adjusted effects were similar (the average β coefficient for psychotic symptoms was 0.18; three associations with psychosis were significant, and only one after Bonferroni correction).

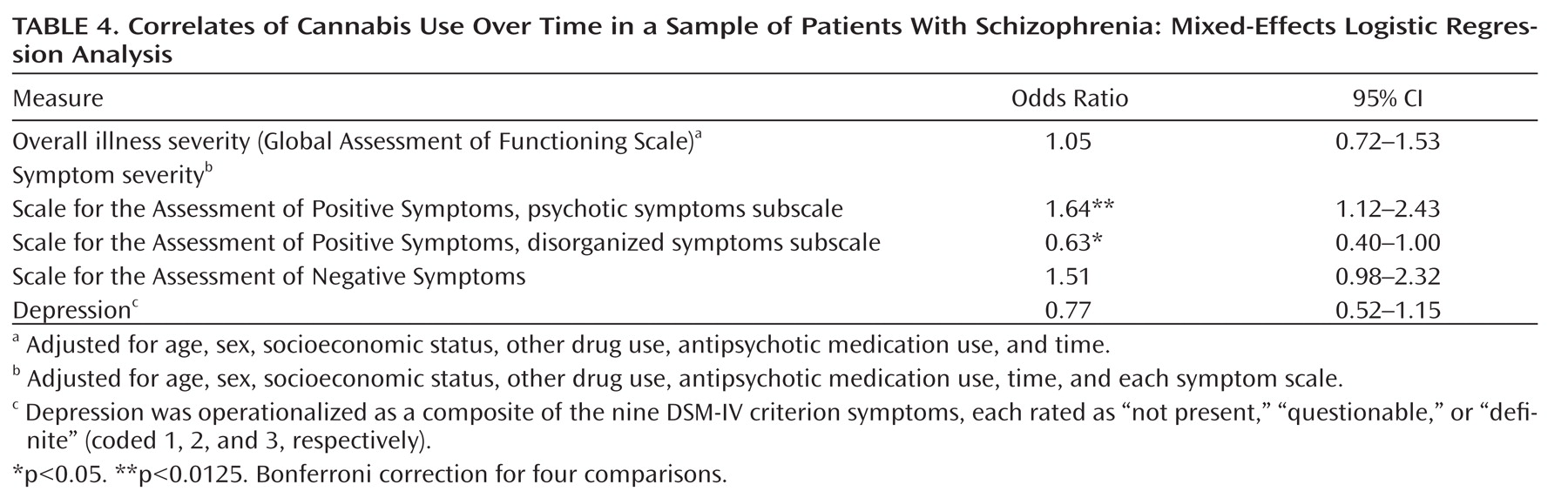

Longitudinal Associations of Cannabis Use and Symptom Severity

The within-person analyses revealed that changes in cannabis status were linked with changes in psychotic symptoms (p=0.012) even after adjusting for the covariates and other symptom domains (

Table 4). Thus, an increase in psychotic symptom severity was associated with a greater likelihood of using cannabis; likewise, a decrease in psychotic symptom severity was associated with a lower likelihood of use. An inverse association with disorganized symptoms (p=0.049) was also observed but did not survive Bonferroni correction. No other effects were significant.

We examined the direction of the identified longitudinal correlation between cannabis use status and psychotic symptoms using structural equation modeling. A cross-lagged model that included the five assessment waves as well as prebaseline cannabis exposure (

Figure 1) yielded excellent fit to the data (CFI=0.95, RMSEA=0.05). All paths in the model were significant. Effects of cannabis use on later psychotic symptoms (average b=0.14) and of psychotic symptoms on later cannabis use (average b=0.10) were comparable and statistically significant, indicating a bidirectional relationship. Thus, lower severity of psychotic symptoms predicted cessation of cannabis use, whereas higher severity was associated with an increased likelihood of use at the next assessment. Likewise, cannabis use predicted an increase in severity of psychotic symptoms.

Discussion

Two-thirds of our sample had a lifetime history of cannabis use prior to first hospitalization, and survival analysis confirmed the association of this use with an earlier age at onset of psychosis. Moreover, exposure to cannabis before baseline predicted more severe psychotic symptoms at baseline. Across the 10-year follow-up, rates of current cannabis use ranged from 10% to 18%, and users were found to have more severe psychotic symptoms at two of the five assessment points. These differences in psychotic symptom severity are unlikely to be due to medication use, which was controlled for in the multivariate analyses and did not differ between cannabis users and nonusers at any assessment. In addition, patterns of cannabis use and severity of psychotic symptoms were found to covary over time, and mathematical modeling revealed this relationship to be bidirectional. In other words, changes in cannabis use were predictive of changes in psychotic symptom severity, and vice versa.

These results demonstrate that cannabis use after onset of schizophrenia is associated with more severe psychotic symptoms over a 10-year follow-up, the longest reported assessment period to date. This study builds on previous findings that cannabis exposure is most strongly associated with psychotic symptoms (

18), as well as findings from a briefer longitudinal study that predicted changes in general psychiatric symptoms from cannabis use over the course of a year (

19). Our findings also shed new light on two important issues. First, the link between cannabis use and psychotic symptoms was apparent even after we controlled for negative, disorganized, and depressive symptoms, as well as other drug use, antipsychotic medication use, and demographic variables. Moreover, these other symptoms, as well as overall illness severity, were not significantly associated with use. Disorganized symptoms showed only a marginally significant inverse effect. Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that some individuals used cannabis to obtain relief from disorganized symptoms (

11,

12), but in this sample a more robust association was found with psychotic symptoms. This suggests that individuals with schizophrenia who use cannabis are not more severely ill overall but suffer specifically from more severe psychotic symptoms. Second, this relationship with psychotic symptoms was bidirectional: cannabis exposure predicted severity of psychosis, and individuals with more severe psychotic symptoms were more likely to use cannabis in the future. This is consistent with findings from two recent studies, one conducted in a nonclinical sample (

36) and the other focusing on relapse among individuals with recent-onset psychosis over a 6-month follow-up (

37).

This study had several limitations, although given that these limitations reduced the likelihood of obtaining significant results, our findings are all the more noteworthy because of them. First, the lag between assessments increased over time (to reduce participant burden), which required additional modeling in longitudinal analyses. Second, the time frame of the cannabis use variables changed during the course of the study, affecting the prevalence rates and making it difficult to fully align time frames of cannabis use and symptoms. Both issues constitute important caveats, but we did not find evidence that they affected the longitudinal associations. Third, the number of users at each assessment was relatively small, although the prevalence rates are consistent with previous studies (

1,

7,

8). Fourth, cannabis exposure was not verified with toxicology screens.

The clinical relevance of our findings is underscored by the fact that cannabis use is a potentially modifiable behavior, and successful cessation may lead to appreciable reduction in severity of psychotic symptoms (

19). Although our naturalistic study did not find differences in rates of cannabis use by treatment with antipsychotic medications, clinical studies have shown that antipsychotics may facilitate cannabis cessation in patients by reducing the severity of psychotic symptoms. In fact, there is some evidence that clozapine may be particularly effective for patients with schizophrenia and comorbid substance use disorders (

38). Indeed, it has been suggested that the integration of psychiatric and substance abuse treatments into a single approach for dually diagnosed individuals may produce better results than treating the two issues separately (

39). This remains to be demonstrated empirically, however, as a recent review of treatment for patients with dual diagnoses concluded that the efficacy of integrated treatment is uncertain (

40).

This study demonstrated that exposure to cannabis among patients with schizophrenia is associated with an adverse course of psychotic symptoms, and vice versa. This bidirectional relationship between cannabis use and psychotic symptoms was observed after taking into account other clinical and demographic variables, and it may have implications for future studies of both behavioral and biological treatment interventions. As our understanding of the biology of cannabis use and psychosis continues to improve, it may be possible to identify mechanisms by which exposure to cannabis may influence psychosis, and these mechanisms may become future targets for intervention.