In recent years, there has been a greater appreciation of the elevated prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the schizophrenia population and the liability some treatments have for their development. These cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity, are also important risk factors in the development of dementia (

1–3) as well as more subtle cognitive decrements (

4). However, the impact they have on the cognitive functions of patients with schizophrenia remains underexplored. This area of investigation demands attention because identification of additional causes of cognitive impairment may lead to new developments in treatments, which might be aimed at vascular factors. Indeed, the results of studies of vascular risk factors in Alzheimer's disease have spawned a number of dementia treatment trials of medications targeting vascular risk factors (

5,

6). Therefore, similar treatment targets may prove worthy of investigation in schizophrenia if there is sufficient evidence linking these factors to the cognitive impairment of schizophrenia.

The baseline data from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study (

7) failed to show any relationship between the metabolic syndrome and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. However, neither CATIE nor other investigations have focused on the association of individual vascular risk factors and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Indeed, the CATIE requirement that participants meet at least three of the criteria to be categorized as having metabolic syndrome (

7) may have resulted in the inclusion of a substantial number of individuals with only one or two vascular risk factors in the group designated as not having metabolic syndrome. This may have diluted the measured effects of these individual risk factors on cognitive performance.

We compared the association between individual vascular risk factors and cognitive performance in a large sample of patients with schizophrenia and nonpsychiatric comparison subjects. We hypothesized that patients with schizophrenia and comparison subjects with each of these vascular risk factors would demonstrate poorer cognitive performance than their counterparts who did not have these risk factors. We also made an exploratory assessment of potential interaction effects between a diagnosis of schizophrenia and the presence of these risk factors.

Discussion

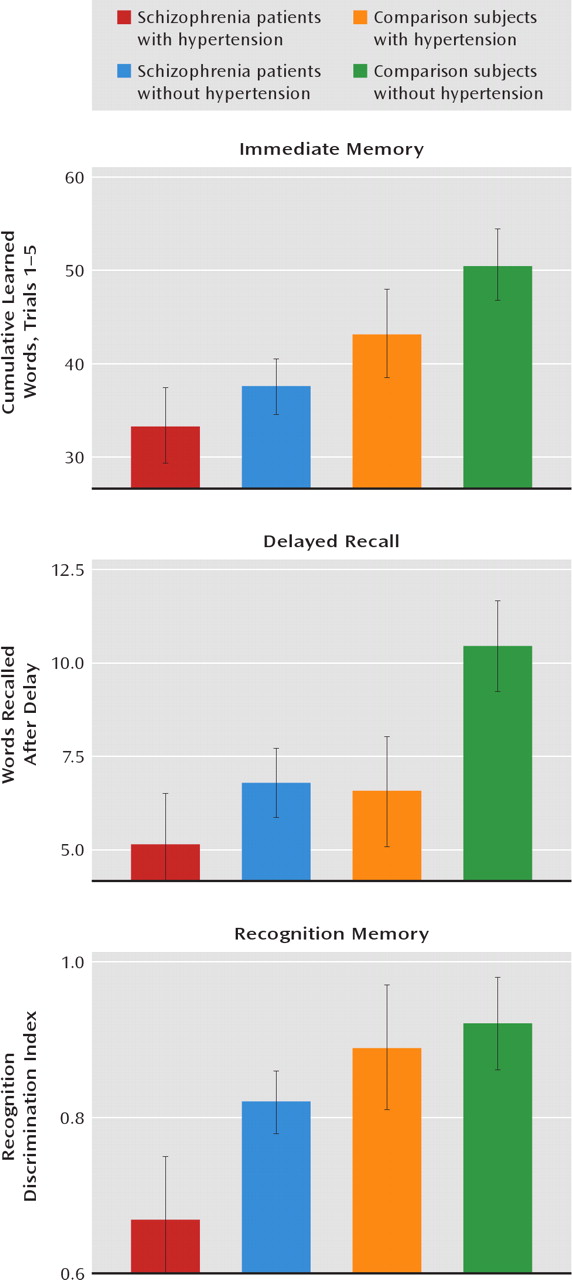

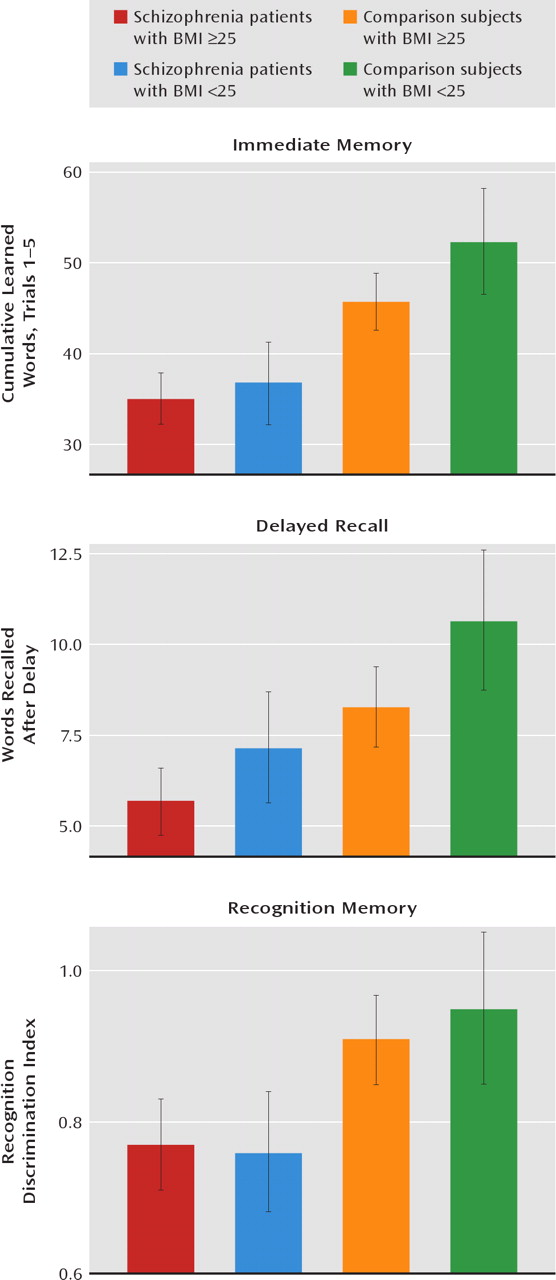

Hypertension was significantly associated with poorer verbal memory performance in patients with schizophrenia and in nonpsychiatric comparison subjects age 29 and older. Moreover, an elevated BMI was more modestly associated with poorer verbal memory performance in schizophrenia patients and in comparison subjects. Although an association between hypertension and elevated BMI and poorer cognitive test performance in persons without schizophrenia has been reported (

18–30), our findings provide the first evidence for an association between the presence of individual vascular risk factors and more severe cognitive impairment in schizophrenia.

There were no significant interaction effects between a diagnosis of schizophrenia and hypertension or an elevated BMI, although the results do indicate larger negative effect sizes for these vascular risk factors in the comparison group (

Tables 2 and

3). However, a diagnosis of schizophrenia alone significantly impaired cognitive performance, and hypertension and an elevated BMI exerted additional negative influences on cognitive performance in schizophrenia patients.

These findings are in agreement with other studies of nonpsychiatric populations that have shown associations between hypertension and poorer cognitive performance (references

18–22, for example). Interestingly, the effects of hypertension in our study subjects, all of whom were being treated with antihypertensive medications, were restricted to verbal memory. Other studies have similarly demonstrated a restricted pattern of verbal memory impairments in hypertensive patients receiving treatment (

23). In contrast, untreated hypertensive patients show a more widespread pattern of neuropsychological impairments, including in executive functioning and motor speed, in addition to verbal memory impairments (

23,

24). These findings suggest that there may be transient abnormalities related to untreated hypertension resulting in cognitive impairments that are not present once treatment is started. Should this be the case in schizophrenia patients, it would have major implications for treatment focus, especially given the high rate of untreated hypertension in this population (

23). Alternatively, the deleterious effects of hypertension may be restricted to the cognitive domain of verbal memory in schizophrenia patients, regardless of antihypertensive treatment. However, even such a restricted pattern of negative effects on cognitive performance in schizophrenia patients would have significant implications for many aspects of functioning in everyday life. Indeed, evidence suggests that verbal memory is a key predictor of everyday life functioning in schizophrenia (

31–34).

Although a BMI >30 has been traditionally accepted as a risk for cognitive impairment, a threshold of only 25 was sufficient to negatively influence cognitive function in the participants in our study, albeit more modestly than in investigations of nonpsychiatric subjects (

26–30). Although not often reported, others have noted a BMI threshold of 25 as a risk for cognitive impairment in nonpsychiatric subjects (

35).

Hypertension and obesity are well-established risk factors for atherosclerosis (see reference

36 for a review), which raises the possibility that atherosclerosis is the final common pathway through which these risk factors impair cognition. Supporting this possibility is the observation that dementia is correlated with atherosclerosis severity (

37). However, nonvascular mechanisms for the association of hypertension and obesity with cognitive impairment have been suggested. For obesity, some have postulated direct actions of adiposity on neuronal tissue through neurochemical mediators produced by the adipocyte (

38). Leptin, a protein secreted predominantly by adipocytes, regulates appetite and may play a role in learning and memory (

39). In animal models, leptin facilitates learning, spatial memory, and long-term potentiation (

40) and has been shown to enhance

N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor function and modulate synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (

41). Interestingly, higher leptin levels have been associated with greater BMI (

42), suggesting leptin resistance as a causal pathway from obesity to cognitive impairment. In support of this notion is the observation that obesity and aging are also associated with hyperleptinemia and leptin resistance (

43).

For hypertension, alternative mechanisms to atherosclerosis underlying its association with cognitive impairment include oxidative stress (

44) and increased activation of the renin-angiotensin system. The continuous exaggeration of the human renin-angiotensin system in transgenic mice impairs cognitive function (

45). The administration of an angiotensin II type 2 receptor antagonist to these transgenic mice ameliorates this cognitive impairment and reduces blood pressure (

45). In contrast, treatment with hydralazine in these mice does not reverse the cognitive impairment, although it does lower blood pressure (

45). Clinical studies in humans have suggested that blockade of the renin-angiotensin system can prevent cognitive impairment associated with hypertension (

46).

Our findings have important clinical implications. Patients with schizophrenia experience a much higher prevalence of vascular risk factors than does the general population (

47). Although lifestyle factors contribute to this elevated prevalence (

48), treatment with certain second-generation antipsychotics also increases risk, including for increased weight and hypertension (

49). Compounding this problem is that patients with schizophrenia are also undertreated for these vascular risk factors relative to the general population. For example, baseline data from the CATIE study showed that rates of nontreatment for schizophrenia patients ranged from 30.2% for diabetes to 62.4% for hypertension to 88.0% for dyslipidemia (

25).

Because vascular risk factors represent common and modifiable factors, these findings raise the possibility that their treatment may significantly improve cognitive outcome in schizophrenia. Indeed, antihypertensive treatment in other populations has been associated with cognitive improvement in several studies (

20,

22,

46). Given the high rate of undertreatment for hypertension in schizophrenia patients and the significantly greater levels of cognitive impairment in untreated compared with treated hypertensive patients (

23,

24), adequate treatment of hypertension alone could have a significant impact on cognitive outcome in the general population of patients with schizophrenia. Furthermore, caloric restriction in normal to overweight elderly individuals has been associated with improvement in memory over a 3-month interval (

50), raising the possibility of another point of intervention for the cognitive impairments of schizophrenia.

While intriguing, the results presented here have limitations. First, we were unable to assess glucose intolerance because there were insufficient numbers of affected persons in the comparison group. Similarly for hyperlipidemia, there were insufficient numbers for analysis. Moreover, this study examined cross-sectional relationships between vascular risk factors and cognitive functions. These relationships in demented and nonpsychiatric groups are more complex and may be influenced by the timing and duration of exposure to these factors (

21). Finally, the hypertensive participants in our study were all being treated for hypertension, which does not refiect the undertreatment observed in the general population of patients with schizophrenia. However, this bias would seem to have diluted the deleterious effects of hypertension on cognition as indicated by data from the comparison group. These issues indicate a need for further studies not only to replicate these results but to extend them to effects of other vascular risk factors. This may eventually lead to the study of drug targets not yet considered for schizophrenia.