According to dual-system theories (

4,

5), actions can be supported by either a goal-directed or a habit system. When the goal-directed system exerts dominant control, actions are performed to achieve desirable goals or to avoid undesirable outcomes. Washing one's hands before preparing a meal, for example, may constitute a goal-directed action that is performed to avoid contamination. However, after multiple repetitions of this action, the habitual system can begin to exert dominant control over behavior (

6–

8), leading to greater efficiency but also to a loss of behavioral flexibility. This becomes apparent when a person commits a “slip of action,” such as thoughtlessly washing her hands upon entering the kitchen when her intention was to retrieve a set of keys. Here, the kitchen environment has directly triggered the habitual response of hand washing. We hypothesize that in OCD, persistent reliance on the habitual system leads to compulsive responding, such as repetitive hand washing. Habitual responses for undesirable outcomes can be induced in animals by lesioning the prelimbic cortex (

9–

11), suggesting that this area is crucially involved in goal-directed action control. More recently, functional MRI (fMRI) studies have provided correlational evidence that the ventromedial prefrontal cortex is similarly involved in goal-directed action control in humans (

12,

13).

It has been suggested that in drug abusers, the dominance of habitual response control contributes toward the subjective “must do!” experience that commonly accompanies a compulsive urge (

14). Based on behavioral parallels between habits and OCD compulsions, we hypothesized that a deficit in goal-directed action control, and a consequent overreliance on habit formation, may underlie compulsivity in OCD. Furthermore, there is consensus that dysfunction in the orbitofrontal and cingulate cortices and in the caudate nucleus plays an important role in OCD (

2,

15,

16). These same regions have been implicated in goal-directed control (

10,

12,

13,

17,

18) and habit learning (

19–

21). Therefore, impairment of this frontostriatal loop (

22) in patients with OCD is likely to cause disruptions in the goal-directed system and cause an overreliance on habitual control.

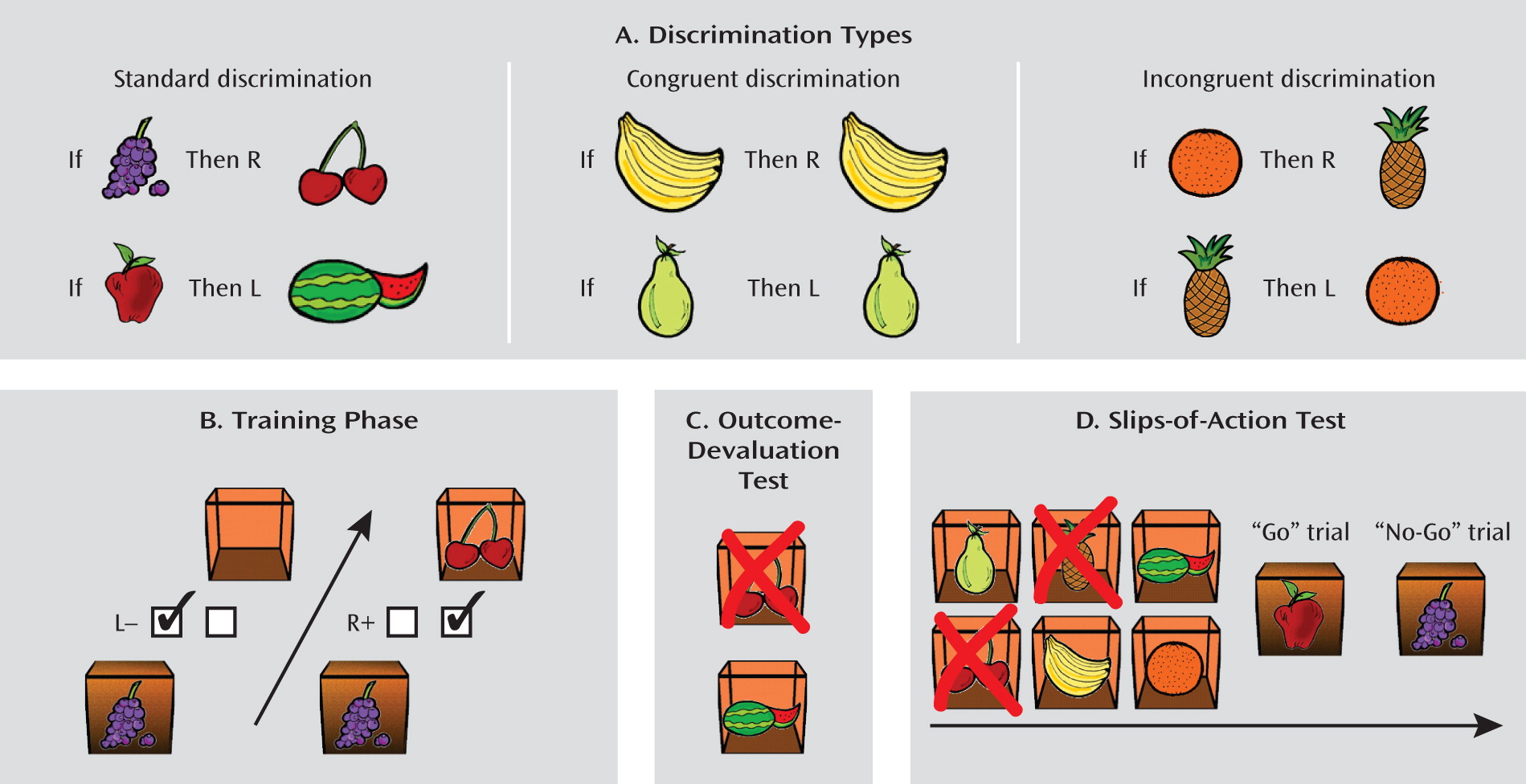

To test this hypothesis, we employed a series of tasks, as depicted in

Figure 1. During the initial training stage (

Figure 1B), participants learned to respond to different stimuli in order to gain outcomes that would earn them points. A baseline of habitual behavior was established by using incongruent events on a subset of trials, which have been shown to elicit habitual responses in healthy participants (

13,

23,

24) (

Figure 1A; see Method section). After the training stage, we tested relative goal-directed versus habitual control. The first of three tests was an outcome devaluation test (

Figure 1C), in which participants must use their knowledge of the relationship between their actions and the various outcomes to direct their choices to valuable outcomes (and away from devalued outcomes). Second, we administered a questionnaire that explicitly probed knowledge of the relationships between stimuli, responses, and outcomes. Finally, we used a novel slips-of-action test (

Figure 1D), in which participants could respond to stimuli that signaled either still valuable or devalued outcomes. Here, the goal-directed and habitual systems compete for behavioral control, and this provides a more sensitive index of which system retains relative control. Responses to devalued outcomes, or slips of action, imply a lack of sensitivity to outcome value and are therefore indicative of the dominance of habitual response control. We predicted that overreliance on the habit system would cause patients with OCD to commit more slips of action than the comparison subjects.

Results

Table 3 summarizes the accuracy and reaction times for the standard, congruent, and incongruent discriminations.

Table 4 summarizes the scores earned by participants (out of 2 possible) on the questionnaire that assessed explicit knowledge of the instrumental contingencies.

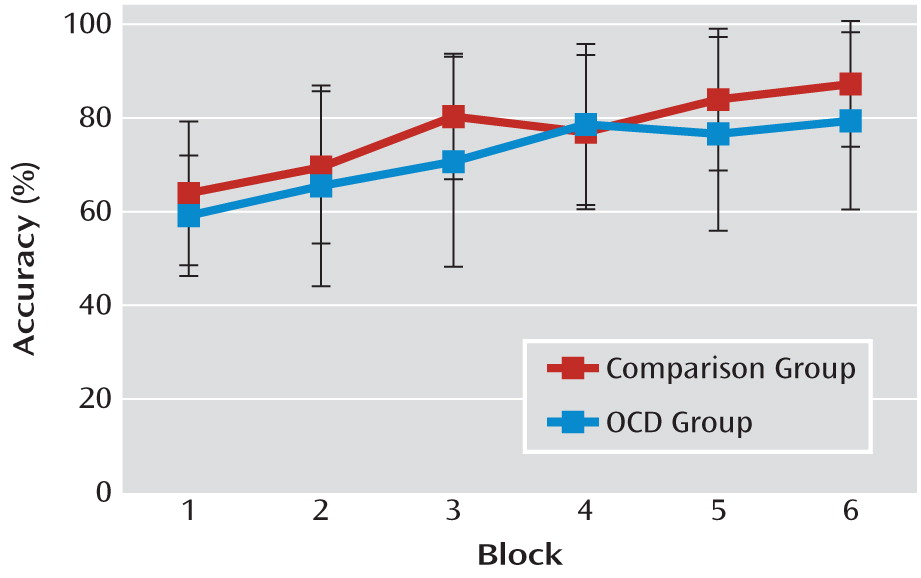

There was no significant difference between patients with OCD and comparison subjects in rate of learning (

Figure 2), nor was there a significant group-by-discrimination (congruent/standard/incongruent) interaction. A nearly significant effect of discrimination was observed (F=2.96, df=2, 98, p=0.06), indicating a tendency toward differential learning rates that was dependent on discrimination type. Preplanned pairwise comparisons (using the Bonferroni correction) showed that participants performed better overall on the congruent discrimination (mean=78%) than on the incongruent discrimination (mean=72%, p<0.05), while performance on the standard discrimination (mean=74%) did not differ from performances on either the congruent or incongruent discriminations. There was neither a group difference in reaction time nor a group-by-discrimination interaction.

Instructed Outcome Devaluation Test

In line with our hypothesis, a significant group effect was observed (F=4.08, df=1, 49, p<0.05), with average values of 72% and 60% correct responses in the comparison and OCD patient groups, respectively, indicating that deployment of goal-directed knowledge was impaired in the patient group. We also observed a significant discrimination main effect (F=14.66, df=2, 98, p<0.001). Consistent with previous studies using this task, pairwise comparisons revealed that performance on the incongruent discrimination (mean=48%) was worse than on the congruent (mean=82%, p<0.0001) and standard (mean=71%, p=0.001) discriminations. Scores on the congruent and standard conditions did not differ significantly, and there was no discrimination-by-group interaction, illustrating that both groups performed worse on the incongruent discrimination relative to congruent and standard discriminations. Reaction times were not affected by group or discrimination type.

Slips-of-Action Test

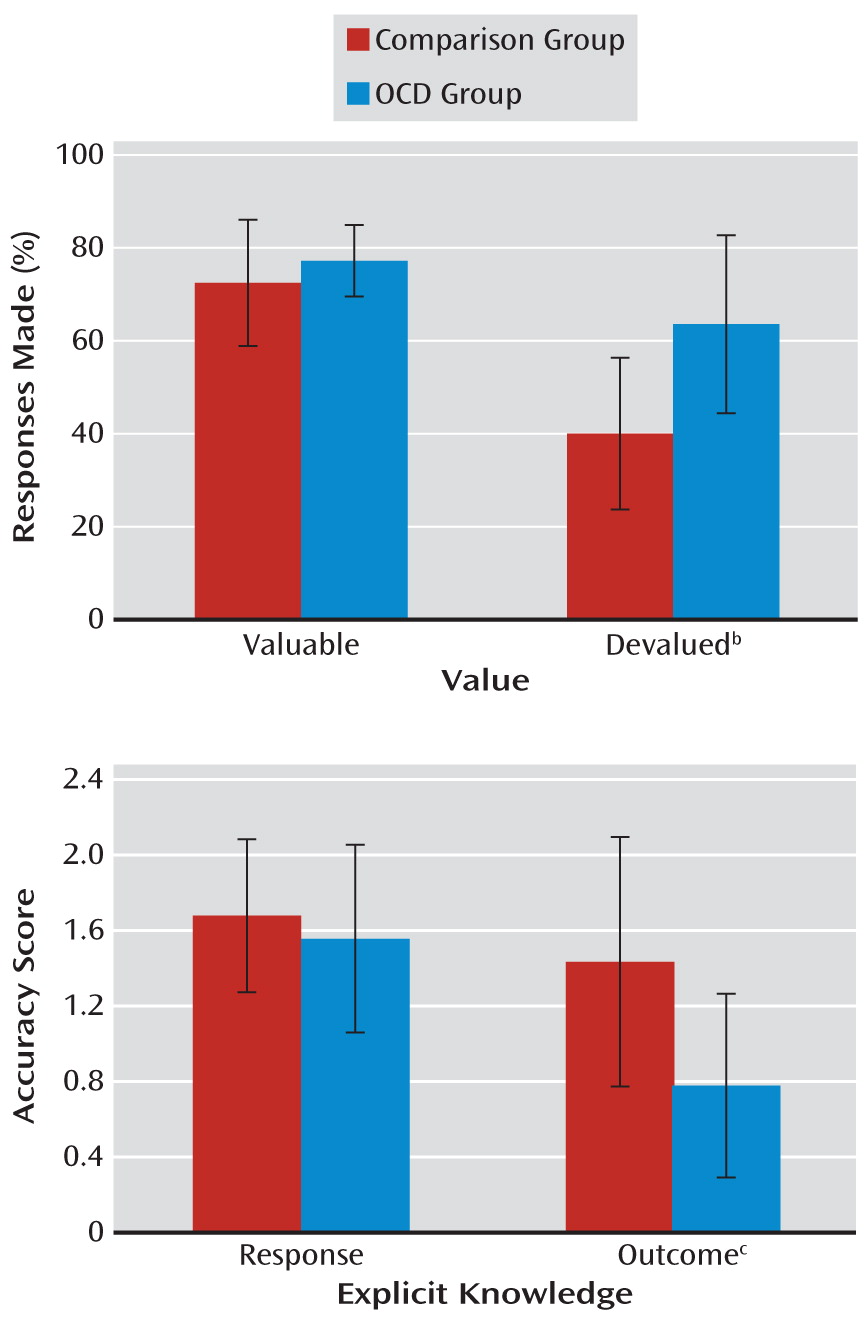

A significant group-by-devaluation interaction (F=6.70, df=1, 38, p<0.05) was investigated with tests of simple effects. While there was no group difference in the level of responding for valuable outcomes, patients with OCD responded more often to stimuli associated with devalued outcomes than comparison subjects. These findings reveal that responses were under dominant habitual control in patients with OCD, thereby rendering their behavior insensitive to changes in outcome value (F=17.43, df=1, 38, p<0.001) (

Figure 3). Separate group analyses revealed that while both groups showed a devaluation effect (i.e., overall fewer responses to stimuli with devalued than valued outcomes), this effect was much more pronounced in comparison subjects (F=3.61, df=1, 19, p<0.001) than in patients with OCD (F=8.69, df=1, 19, p<0.05).

To investigate whether selective response suppression was directly related to symptom severity in the OCD patient group, we conducted Pearson correlational analyses on the difference scores (responses to stimuli for valuable outcomes minus responses to stimuli for devalued outcomes) and Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale scores. We found a significant negative correlation (r=–0.56, p=0.01), indicating that OCD symptom severity predicted slips of action—failure to withhold responses toward devalued outcomes.

Finally, we investigated the significant devaluation by discrimination interaction (F=29.602, df=2, 76, p<0.001) using tests of simple effects. These tests confirmed that all participants responded fewer times when the outcome was devalued as opposed to still valuable on both congruent (F=119.53, df=1, 38, p<0.001) and standard (F=11.02, df=1, 38, p<0.01) discriminations. However, as predicted, outcome devaluation failed to affect the number of responses on incongruent trials, which tend to be solved by habit strategy. There was no three-way interaction.

Questionnaires of Response and Outcome Knowledge

All of the participants completed a questionnaire to test their explicit knowledge of responses and outcomes. The scores on the questionnaires could be 2, 1, or 0 for each of the discriminations. A significant main effect of discrimination (F=7.06, df=2, 98, p<0.01) was investigated using Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons. Overall, participants' explicit knowledge of the congruent contingencies was better than knowledge of the standard and incongruent contingencies (p<0.05 in all cases). Crucially, there was an interaction between group and explicit knowledge (F=8.31, df=1, 49, p<0.01). Simple effects analyses revealed that while knowledge of the appropriate responses to the stimuli did not differ between comparison subjects and patients with OCD, knowledge of the associated outcomes was significantly worse in patients (F=14.915, df=1, 49, p<0.001) (

Figure 3). Furthermore, the patients' outcome knowledge, and not response knowledge, was positively correlated with difference scores from the slips-of-action test (r=0.61, p<0.005), indicating that the failure to acquire outcome knowledge during the training stage was associated with habitual response control during the slips-of-action test.

Additional Analyses Controlling for Differences in Anxiety and Depression

Stress (

33,

34) and anxiety (

35) can cause impairments in goal-directed action control. To investigate whether anxiety contributed to the group differences observed, we used analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) with state and trait anxiety scores from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (

32) as covariates. As the OCD patient group had higher rates of depressive symptoms than comparison subjects, MADRS scores were included in separate ANCOVAs for each stage of the task. None of these effects was significant.

Discussion

Using an instrumental learning task, we present the first direct experimental evidence of a disruption in goal-directed action control in OCD. Healthy comparison subjects and patients with OCD were equally successful at using external feedback to guide instrumental choice between right and left responses, demonstrating that feedback learning was unaffected in OCD. To investigate the underlying learning mechanisms employed during the training stage, we first investigated goal-directed (action-outcome) learning using an instructed outcome devaluation test. The patients with OCD demonstrated weaker knowledge of the causal relationship between actions and their respective outcomes, suggesting a disturbance in goal-directed action control.

To investigate this possibility more directly, we developed a novel slips-of-action test in which the goal-directed system must compete with the habit system for control. Consistent with the habit hypothesis of OCD, patients showed a marked lack of sensitivity to devaluation. Furthermore, we found that symptom severity was predictive of poor performance on the slips-of-action test. We investigated the basis of this deficit using a response and outcome knowledge questionnaire. While knowledge of the correct responses to stimuli was intact in the OCD group, the patients showed a selective deficit in knowledge of the resulting outcomes. Furthermore, outcome—and not response—knowledge was found to predict performance on the slips-of-action test. Taken together, these findings suggest that failure to engage the goal-directed (action-outcome) system mediated slips of action in patients with OCD. We propose that a general impairment in goal-directed action control, with a consequent overreliance on habits, may contribute to the relatively inflexible behavior observed in patients with OCD and furthermore may play a part in the development of compulsivity.

It is evident that patients with OCD do not develop compulsions in every aspect of their lives. Rather, they develop avoidance compulsions related to specific obsessions. It may be critical that the goal of an avoidance response (e.g., hand washing) is not to obtain a tangible outcome but rather to bring about a nonevent (e.g., not contracting an illness). As this nonevent has a high likelihood of occurrence and can cause a generally reinforcing sense of relief, this might make avoidance behavior particularly sensitive to habit formation. The example of compulsive hand washing can be used to illustrate the theoretical overlap between habit formation and compulsivity in OCD. When probed, patients report that they are aware that hand washing has little bearing on whether or not they will contract the feared illness. However, in spite of this knowledge, the behavior persists. A lack of sensitivity to the direct outcomes of actions but preserved sensitivity to broader goals—such as relief from anxiety triggered by obsessions—might explain this phenomenon. This account can explain why patients with OCD have no deficit in their ability to perform the task to gain the broader outcome of earning points but show a lack of sensitivity to the more direct outcomes of their actions (which fruit they won in order to obtain those points). We postulate that the observed deficit constitutes a vulnerability factor for OCD, but the presence of obsessions is likely critical for compulsions to develop.

Numerous functional neuroimaging studies have shown that the orbitofrontal and ventromedial prefrontal cortices, and less consistently the caudate nucleus, are engaged when healthy volunteers perform goal-directed actions (

12,

36). Importantly, dysfunction in this orbitofronto-striatal circuit has been consistently implicated both in many aspects of OCD symptomatology (

37–

39) and in aspects of cognitive flexibility and deficits in motor inhibition associated with the disorder (

40). Furthermore, an fMRI investigation (

13) implicated the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in goal-directed performance on our instructed outcome devaluation test. Our finding of impaired performance on this test by patients with OCD is therefore consistent with research implicating a dysfunction in this goal-directed corticostriatal pathway in OCD. The dysfunction forces patients to rely instead on a parallel, habitual system, which includes the putamen and possibly the sensorimotor cortex in humans (

20,

41).

Although previous studies have provided evidence for abnormalities in implicit learning in OCD at both the behavioral and neural levels (

42–

44), this is the first study of habit formation as defined by Dickinson and colleagues (

4,

5). The mechanisms underlying implicit learning and habits may well overlap, but research is needed to elucidate this. Critically, our data do not imply that habit formation is exaggerated in patients with OCD. Rather, we were able to show that a substantial goal-directed action control deficit tipped the balance toward reliance on habits. The question remains whether this imbalance offers an account of ego-dystonic behavior in OCD. In our study, patients often reported that they were aware of their impaired outcome knowledge and their reliance on habits (see Patient Perspective). It is therefore possible that egodystonic experience only arises after extensive behavioral repetition or only in the context of patients' specific obsessions.

We did not find evidence for superior learning of the standard discrimination relative to the incongruent one, which has been previously reported for young, healthy volunteers and which is thought to reflect the additional support of the goal-directed system in the standard discrimination (

13). The fact that our healthy comparison subjects failed to show the congruency effect, possibly because the average age in the comparison group was higher (

45), indicates that the congruency comparison cannot be used in our study as a reliable measure of outcome learning. However, the overall lack of a congruence effect does not bear on our robust demonstration of deficiencies in outcome knowledge in patients with OCD.

The majority of patients with OCD were taking SSRIs, and a small number were receiving antipsychotics. This represents a significant limitation of our study, as we cannot exclude the possibility of a medication effect. Some evidence from animal research has suggested that serotonin depletion in the orbitofrontal cortex can reduce sensitivity to outcome value (

46,

47); therefore, it is possible that unmedicated patients would show an even more pronounced deficit. Nevertheless, in subsequent studies an appropriate clinical control group (e.g., drug addicts, pathological gamblers) or an unmedicated OCD patient group should be included to determine whether the observed deficit is specific to OCD.

In conclusion, patients with OCD showed no deficit in their ability to use feedback to guide instrumental learning. However, patients' knowledge of the outcomes following their responses was impaired, leading them to commit slips-of-action errors. These results indicate that patients' performance depended more strongly on habitual control at the expense of goal-directed control. We therefore propose that, as has been suggested for drug and gambling addiction, an imbalance between habitual and goal-directed control may underlie the urge to perform compulsive acts (

14). Although additional research will be necessary to corroborate this account, in light of convergent neurobiological and behavioral evidence, we postulate that this imbalance may contribute to the compulsive behaviors typical of OCD.