Sedative properties associated with antipsychotic medications (

10) may help to explain their broadened use in nonpsychotic patients. Some have suggested that from a pharmaco-epidemiological perspective, these drugs should be considered “antineurotic” or “hypnotic” medications rather than antipsychotics (

11). In this context, patients presenting with anxiety disorders represent a large potential population for antipsychotic treatment. Clinical guidelines recommend serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors as first-line pharmacologic treatments for anxiety disorders (

12), although a significant number of patients do not respond to an adequate trial of these medications. Given risks of cognitive side effects, withdrawal syndrome, and the potential for abuse associated with benzodiazepines, antipsychotic medications have been viewed as playing a role in treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (

12).

The present report examines recent national trends and patterns in the antipsychotic medication treatment of anxiety disorders by office-based psychiatrists. Among office visits in which an anxiety disorder was mentioned across a 12-year period (1996–2007), antipsychotic treatment patterns and time trends were examined by patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. We predicted a broad-based national increase in the rate of antipsychotic prescribing in office visits for anxiety disorders, with particularly pronounced increases among anxiety disorder visits that did not include co-occurring diagnoses and those in which the diagnoses lacked FDA-approved antipsychotic indication. We further predicted that these increases would be largely attributable to expanded prescribing of second-generation antipsychotics.

Method

Sample

Encompassing a 12-year period (1996–2007), data were drawn from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, a multistage probability survey of visits to office-based physicians of all medical specialties engaged in direct patient care. Survey response rates varied from 62.9% to 77.1% (median=67.7%). A systematic random sample of visits to each physician was drawn during a randomly selected 1-week period. We limited the sample to 4,166 outpatient visits to psychiatrists in which an anxiety disorder was diagnosed. The following six anxiety disorder classes were included: traumatic stress disorders, panic disorder/agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), phobias, and other anxiety disorders.

Assessments

For each visit, the psychiatrist or member of the psychiatrist's staff provided information about patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and psychotropic medications prescribed or supplied to the patient. In the present article, the term “prescribed” is used to refer to prescribed or supplied medications.

Psychotropic Medications

Up to six medications were recorded in each visit from 1996 to 2002. Starting in 2003, up to eight medications were recorded. To make years comparable in the present study, we limited the maximum number of medications to the first six listed in all years. Antipsychotic medications, including first- and second-generation agents, as well as antidepressants, sedative/hypnotics, and mood stabilizers were included. Psychotropic agents included in each medication class are presented in the Appendix in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article. Visits were classified as either antipsychotic visits, in which the patient was prescribed at least one antipsychotic, or nonantipsychotic visits, in which the patient was not prescribed an antipsychotic medication.

Antipsychotic indication status was based on FDA-approved indications for antipsychotic treatment as of May 20, 2010. One or more antipsychotics have been approved for the following illnesses: schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, pervasive developmental disorder, and major depressive disorder when coprescribed with an antidepressant. Although no antipsychotic medications are currently approved for the treatment of schizophreniform disorder, since most patients with this disorder transition to schizophrenia within 1 year, we deemed schizophreniform disorder an approved antipsychotic indication. We considered all visits in which any of these clinical diagnoses was assigned as visits for which FDA indication for antipsychotic treatment was established, regardless of whether the visit occurred before or after the first FDA-approved antipsychotic use for that diagnosis. To cast a broad net in capturing FDA-approved antipsychotic indications, we considered a visit as establishing an approved indication if any antipsychotic was FDA-approved for the diagnosis assigned, regardless of the specific antipsychotic drug prescribed. We also disregarded age when considering approved antipsychotic indications.

Up to three diagnoses were recorded for each visit. Anxiety disorder diagnoses were classified into the following six broad categories: 1) traumatic stress disorders (ICD-9-CM: 309.81, 308.3), which included posttraumatic and acute stress disorders; 2) panic disorder/agoraphobia (ICD-9-CM: 300.01, 300.21, 300.22); 3) generalized anxiety disorder (ICD-9-CM: 300.02), characterized by excessive/uncontrollable worry with associated somatic symptoms; 4) OCD (ICD-9-CM: 300.3); 5) phobias (ICD-9-CM: 300.2, 300.23, 300.29), characterized by marked, persistent, and interfering fear of specific objects or situations, including specific and social phobias; and 6) other anxiety disorders (ICD-9-CM: 293.84, 300.0, 300.09, 309.21, 313.0), which included anxiety state (unspecified), other anxiety states, anxiety disorder as a result of a general medical condition, substance-induced anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and overanxious disorder. Primary source of payment was classified as private insurance, public insurance, self-pay, or other.

Other variables were patients' sex, age range (≤17 years, 18–34 years, 35–54 years, ≥55 years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Caucasian, non-Hispanic African American, Hispanic, other), visit sequence (returning patient versus new patient), and comorbidity (single or multiple anxiety disorders only, anxiety diagnoses and other classes of comorbid axis I disorders). Visits for anxiety disorders in which other classes of comorbid mental disorders were also determined were further broken down into the following three overlapping groups: comorbid mood disorders (ICD-9-CM: 296.0–296.9, 298.09, 300.4, 301.13, and 311), comorbid psychotic disorders (ICD-9-CM: 295 and 297–299), and other comorbid disorders.

Analysis

First, we charted the change in the number of visits for anxiety disorders in which an antipsychotic medication was prescribed and considered this change relative to trends in visits in which antidepressants or sedative/hypnotics were prescribed across the same period. We next examined sociodemographic and clinical correlates of antipsychotic prescribing in visits for anxiety disorders. Third, we assessed time trends in antipsychotic medication treatment in visits for anxiety disorders across strata based on clinical and sociodemographic characteristics, adjusting for the effects of other demographic and clinical characteristics.

Analyses were adjusted for visit weights, clustering, and stratification of data using design elements provided by the National Center for Health Statistics. When adjusted for these elements, survey data represent annual visits to U.S. office-based physicians (

16). We examined time trends in visits in which antipsychotic medication was prescribed using multivariate binary logistic models. The survey year was transformed by subtracting 1996 from the year and dividing the results by 11. Thus, the transformed value was 0 for the year 1996 and 1 for the year 2007. The odds ratios associated with this transformed variable represent change in the odds of visits in which antipsychotic medication was prescribed across the entire study period. Analyses were conducted using STATA, version 11 (StataCorp., College Station, Tex.).

Discussion

The findings of this study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, despite adjustment for several visit and patient characteristics, including clinical diagnosis, comorbidity, and payment source, we cannot exclude the possibility that trends reflect residual confounding as a result of changes in unmeasured clinical differences across years. For example, although there were not increases across time in comorbid psychotic or mood disorders in office visits for anxiety disorders, there was an increase in overall comorbid disorders, which we consequently accounted for in adjusted time-trend analyses. Second, the survey does not record previous clinical response to psychotropic regimens, measure the effects of antipsychotic treatment on clinical outcomes, or assess the duration of antipsychotic trials with patients' current or previous physicians. These shortcomings constrain the clinical meaning of visit sequence. It is accordingly not possible to determine at the patient level whether observed antipsychotic prescribing is associated with increased or decreased use of other medication classes. However, cross-sectional analyses demonstrate similar but less impressive increases across time in visits for anxiety disorders in which antidepressant and sedative/hypnotic medications were prescribed and no trend in mood stabilizer prescribing. At a population level, these patterns suggest that antipsychotics are augmenting, rather than replacing, other medication classes in the management of anxiety disorders. Nevertheless, a proportionate increase was also noted in the use of antipsychotic medications in the absence of other medication classes (

Table 1). Third, information was not available on dosing, which is likely considerably lower in anxiety disorders than in psychotic disorders. For clozapine and olanzapine, the balance of evidence suggests a dose-response relationship with metabolic side effects (

17). Fourth, the analysis may misclassify combinations of medications used by patients who receive psychiatric care from multiple physicians. Fifth, because our analysis is limited to office-based psychiatrists, the results do not generalize to other specialties and treatment settings where patients receive mental health services. Sixth, clinical diagnostic determinations may vary over time with changing practice patterns. Without structured diagnostic interviews, it is not possible to examine such variations. It is also not possible to determine the extent to which survey data undercount psychotic disorders or other conditions, fail to document diagnosed mental disorders, or do not capture nonpsychiatric targets of antipsychotic treatment. Seventh, the two most recently approved antipsychotics, asenapine and iloperidone, were not included in the present analysis. Finally, because the survey records visits rather than patients, some patient duplication may occur.

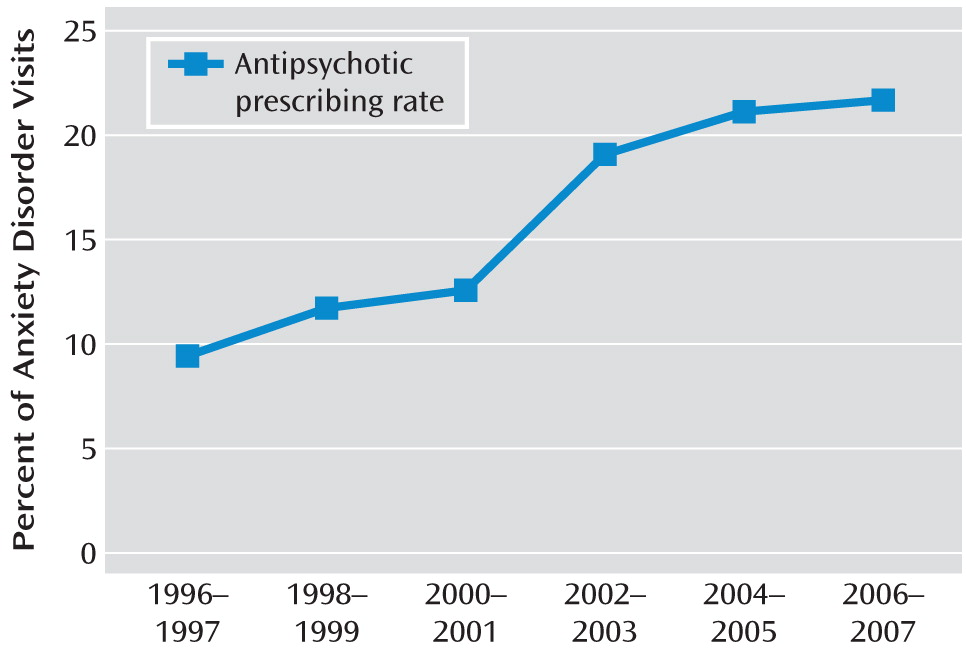

Despite these limitations, the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey offers a national statistical portrait of trends in antipsychotic treatment of anxiety disorders in office-based psychiatry. From 1996 to 2007, there was a roughly twofold increase in the rate of antipsychotic prescribing for anxiety disorders in this practice setting. The proportion of visits for anxiety disorders in which an antipsychotic medication was prescribed increased from roughly one in 10 visits to roughly one in five visits. This finding extends earlier reports of increasing overall psychotropic treatment for individuals with anxiety disorders (

18) and increasing antipsychotic prescribing, particularly with second-generation antipsychotics, in the general population of outpatients (

1,

19). Growth in antipsychotic treatment for anxiety disorders has been broad based, with the most pronounced increases among new patients, privately insured patients, and patients diagnosed with panic disorder (among other groups).

The reasons for these trends remain unclear. Thus, changes in patient characteristics, including increasing severity of illnesses encountered in outpatient practice and greater prevalence or recognition of comorbidities, offer possible explanations. We found an overall association between comorbid psychiatric diagnoses and prescription of an antipsychotic medication. However, across the study period, the antipsychotic prescribing rate roughly doubled among office visits in which only anxiety disorders were diagnosed. Changes in diagnosed psychiatric comorbidity cannot fully account for the observed trends in antipsychotic prescribing.

Greater patient or physician emphasis on symptom reduction, alongside increased acceptance of off-label antipsychotic prescribing, may have contributed to the observed trends (

20). Some psychiatrists may generalize from their clinical experience, treating severely depressed patients with antipsychotic medications (

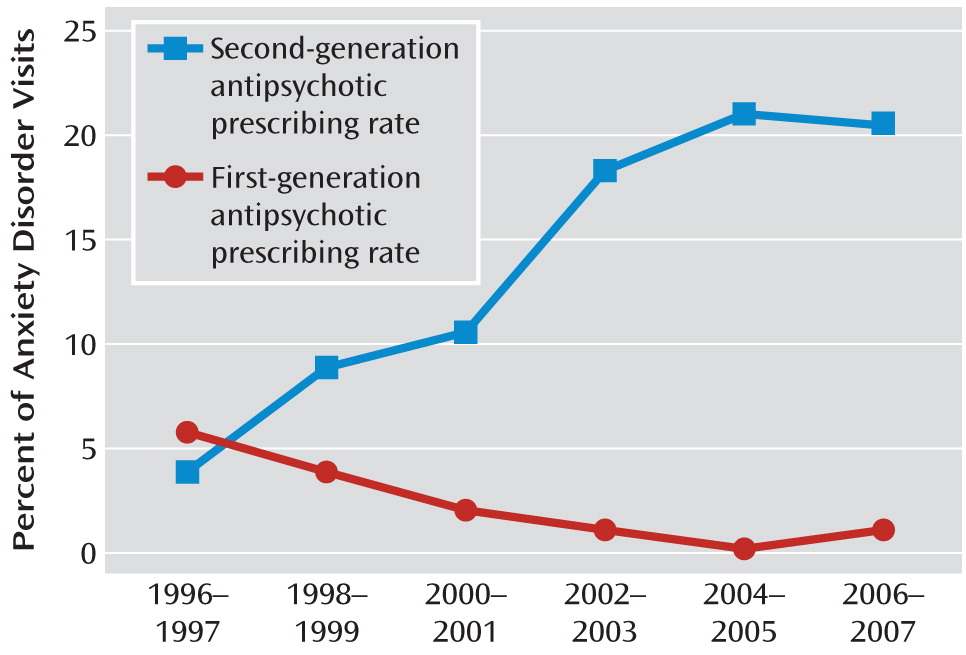

21), to those patients with anxiety disorders. The availability of new antipsychotics, including olanzapine (1997), quetiapine (1997), ziprasidone (2001), aripiprazole (2002), and paliperidone (2006), may have further contributed to the overall increased use of antipsychotic treatment. The observed trends in antipsychotic prescribing in visits for anxiety disorders was attributable to the increased prescribing of second-generation antipsychotics, paralleling earlier reports in general psychiatric outpatient care (

1). An increasing number of office-based psychiatrists are also specializing in pharmacotherapy to the exclusion of psychotherapy (

22). Limitations in the availability of psychosocial interventions may place heavy clinical demands on the pharmacological dimensions of mental health care for anxiety disorder patients. Moreover, the role of outpatient psychiatry may have changed across time, such that office-based psychiatrists have been seeing a growing number of complicated cases (

23).

Medications with anxiolytic properties, such as benzodiazepines, have historically played a prominent role in the treatment of anxiety disorders (

18). The availability of second-generation antipsychotic agents with improved anxiolytic properties over first-generation agents (

24), while offering less sedation (

25), has likely contributed to their clinical role in the treatment of anxiety disorders (

11). The availability of antipsychotics with fewer short-term anticholinergic and extrapyramidal effects than first-generation antipsychotics (

26) may have also contributed to the observed increases.

Antipsychotic prescribing grew especially rapidly among new patient visits. Psychiatrists may be becoming increasingly comfortable with treating anxiety disorders with antipsychotic medications before adjusting current medications or initiating trials of other medication classes. Alternatively, patients referred for psychiatric care may include a larger proportion that has received antipsychotic treatment prior to referral or patients with remaining symptoms despite trials of antidepressants or other medications.

Little is known about the efficacy and safety of antipsychotic regimens for the treatment of many of the common anxiety disorders. Controlled evaluations in this area have been largely confined to treatment-resistant OCD, traumatic stress disorders, and generalized anxiety disorder. Findings from these evaluations have been largely favorable with regard to adjunctive antipsychotic treatment for OCD (

27,

28) and promising but somewhat inconclusive with regard to antipsychotic treatment for traumatic stress disorders (

29,

30). Findings from the small set of controlled evaluations of antipsychotic treatment for generalized anxiety or social anxiety disorders either have found no clinical benefit (

31,

32) or often yielded inconsistent findings across outcomes (

33,

34). In one promising, large controlled trial of generalized anxiety disorder (

35), quetiapine demonstrated significant anxiety reductions relative to placebo, although with higher discontinuation rates relative to paroxetine as a result of adverse events. Controlled evaluations of antipsychotic treatment for panic disorder have not been conducted.

Significant increases in antipsychotic prescribing for patients diagnosed with panic and generalized anxiety disorders suggest that high priority should be given to prospective clinical research on antipsychotics used to treat these disorders. In the meantime, current findings, alongside declining use of psychotherapy (

22), support calls to improve access to established psychosocial treatments for panic and generalized anxiety disorders (

36).

Increasing antipsychotic prescribing in visits in which no diagnosis with an FDA approval for antipsychotic treatment is present may raise concerns over the quality of care. Although off-label prescribing is highly prevalent, there is substantial variation in evidence supporting these practices. Across drug classes, antipsychotic medications rank near the top in off-label use with drug safety concerns and inadequate supporting evidence (

37). However, in the absence of information on antipsychotic dosing and duration, a risk analysis cannot presently be determined. Off-label prescribing of antipsychotics for treating anxiety disorders raises difficult challenges for payers, who must balance the needs for treatment access, clinical flexibility, and prescriber autonomy with concerns over safety, costs, and quality of care.

Prescription of medicines outside of FDA approval is not inherently cause for concern, particularly when there is reasonably consistent supporting evidence from controlled evaluations. Often, however, potentially important clinical differences exist between participants in controlled trials and individual patients in community practice (

38). In these circumstances, physicians must grapple with the difficult task of leveraging the scientific literature against clinical experience. In the pharmacological treatment of complex anxiety disorders, consensus treatment algorithms have been developed to help inform clinical decisions (

39). Some of these algorithms endorse antipsychotics as a third-line treatment. Responsible reliance on clinical guidelines should take into consideration panel expertise, methodological rigor of the consensus development process (

40), sponsorship, and recency.

Although our analyses offer little insight into clinical decision making at the individual patient level, the observed antipsychotic prescribing trends appear to reflect a shift in the balancing of risks versus compelling clinical need in office-based psychiatry. Despite limited controlled data for several common anxiety disorders and emerging safety concerns, prescribing patterns suggest a growing acceptance of antipsychotics in the outpatient psychiatric treatment of common anxiety disorders. With increased antipsychotic use, there will be increased need for metabolic monitoring, especially in patient populations with known risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Prudence further suggests that renewed clinical efforts should be made to limit use of these medications to clearly justifiable circumstances. At the same time, a new generation of research is needed to assess the efficacy and safety of antipsychotic regimens for anxiety disorders, especially in patients who have not responded to other treatments.