Historically, the genetic epidemiology of autism and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has been impaired by a lack of large samples and the fact that it is unusual for individuals with ASD to reproduce. Early twin studies based on very small samples led to the conclusion that ASD has high genetic heritability (

1–

3), primarily as a result of high monozygotic twin concordance and very low dizygotic twin concordance. More recent twin studies have observed a higher dizygotic concordance, leading to a more moderate estimate of genetic heritability (

4).

Generally, recurrence in nuclear families has also been the basis of genetic epidemiologic inference. Over the past several decades, only a handful of such studies have appeared. A few have been derived from epidemiologic surveys (

5–

8), while others have been based on volunteer registries (

9,

10), family history studies (

11,

12), or longitudinal follow-up of couples with an affected child (

13).

Evaluation of recurrence risks in half siblings, both maternal and paternal, can also provide important inferences regarding the genetic epidemiology of ASD. Only a few such studies have appeared, with modest sample sizes (

8,

10). While a higher recurrence risk for full siblings compared with maternal half siblings is an indication of genetic effects, comparison of recurrence risks for maternal half siblings and paternal half siblings and evaluation of timing of births in sibships may reveal clues to nongenetic contributions.

Method

Data Sources

Data on ASD in sibships were derived from the records of the California Department of Developmental Services. The Department, which has been described elsewhere (

4,

14,

15), manages a system of 21 regional centers that coordinate and provide assessments and services for persons with developmental disabilities (including autism and mental retardation) throughout the state of California. To identify nuclear families including both full and half siblings, the electronic client file was linked by staff of the California Center for Autism and Developmental Disabilities Research and Epidemiology to state of California birth certificate files, as described below.

Study Diagnoses

The autism-related diagnoses from this resource have been described previously (

4,

14,

15). For this study, we included as affected with ASD any individual with Department of Developmental Services eligibility for autism or, for children deemed eligible for services based on another condition, a code indicating comorbid ASD or suspected ASD. A twin study derived from the same electronic registry in which individuals were directly assessed with the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (

4) found a high correspondence between the client file diagnoses and ASD as defined using the research instrument score criteria of Risi et al. (

16), with a sensitivity of 94.6% and a specificity of 84.6%. Cases for the initial sample cohort were defined as all individuals born in California between 1990 and 2003 who had ASD as defined above in the electronic files. The electronic registry and birth certificate matching took place at the end of 2010, by which time the youngest individuals in the cohort (born in 2003) would be 7 years old, an age by which ASD symptoms have usually been detected (

15).

Linkage to State of California Birth Certificates

Full and half siblings of affected individuals were identified through linkage of the case file data to California birth certificates. Affected individuals were matched to birth certificates based on first and last name, birth date, birth place, mother’s and father’s names, and Social Security number in later years. The birth certificate files were then searched to find other individuals whose maternal or paternal information matched that of the index case. Information available for matching varied by birth year. During the years 1990–1996, last name (or maiden name) and date of birth were available for fathers and mothers, and first names were available for mothers only. In 1997, Social Security numbers of both parents became available. After 1997, first names became available for fathers, and middle names became available for both parents. The birth certificate files were searched for the years 1990–2003 to identify all children who matched an index case for at least one parent.

Matching criteria required an exact match for Social Security numbers and a near-exact match for names. After 1997, matching was highly precise and led to unambiguous matches and nonmatches. Before 1997, some potential matches were ambiguous, so manual inspection was conducted and resolved many of these cases.

Children whose information matched that for both parents were declared full siblings. Children whose information matched that for one parent but not the other were declared half siblings. The information to define maternal and paternal half siblings was also not comparable because before 1997, first names were only available for mothers. This led to a small number of unambiguous paternal half siblings (for whom paternal first names and/or Social Security numbers were available). To expand the number of paternal half siblings, we instituted an additional matching criterion for fathers based on the observed infrequency of the last name in the entire birth certificate database. If the matching paternal last name for two or more children occurred no more than 40 times in the entire database, along with a date of birth match, the two children were declared paternal half siblings. We determined that at this threshold, the chances were extremely small that two unrelated children would have such matching paternal information.

The initial matching identified 29,074 case families (mean sibship size, 1.99). Of these, 48 (0.17%) had impossible relationships and were excluded. An additional 1,649 families (5.7%) in which full sibling versus half sibling ambiguity was not resolved were excluded. At this step, 299 paternal half siblings were identified and retained. Because the analyses of recurrence were calculated by birth order, we required that the oldest child of a couple be born after 1990 (i.e., leading to removal of families in which the oldest identified child was parity >1, indicating that an older child was born before 1990 and thus not captured in our cohort), which excluded 6,486 families (23.7%). We further excluded 925 families (4.4%) with multiple births. Occasionally, when reconstructing families, one of the other birth order offspring was missing. For these sibships, analyses included individuals up to the first missing birth order offspring. Finally, we excluded 6,413 singleton families (32.1%). These procedures led to a total of 13,533 case families. Within these families, there were 6,621 full siblings and 644 maternal half siblings born after the first affected individual in the family (the remainder were born before any affected siblings were born), allowing for calculation of recurrence risk without reproductive stoppage bias.

Selection of Control Families

For the estimation of population prevalence, we identified two index controls for each index case, matched on sex, birth year, birth location, and mother’s race/ethnicity and age. Index controls were confirmed not to be clients in the same electronic registry. We used procedures identical to those described above, matching controls to state birth certificates between 1990 and 2003 to identify siblings of these control individuals. Qualifying ASD diagnoses were permitted among the siblings of controls. The initial number of control families was 59,285 (mean sibship size, 2.08); after exclusions, the number was 20,981, encompassing 29,384 siblings of index controls (15,160 male, 14,224 female). Control families were slightly larger than case families because of reproductive stoppage in the latter (

17).

The study was approved by the state of California’s Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Recurrence Risks

Recurrence risk is defined as the probability of a second child being affected given that another is already affected. Because recurrence risk analysis of full sibship data can lead to a downward bias in the presence of reproductive stoppage (

17), defined as the curtailment of reproduction after manifestation of ASD in an affected child, we analyzed the sibship (and maternal half sibship) data in a sequential fashion, calculating the recurrence risk (proportion affected) by including only siblings born after an affected individual, stratified by absolute birth order (e.g., birth orders 2, 3, and 4 when the first child is affected; birth orders 3 and 4 when the second child is affected but the first is not). In other words, these counts excluded unaffected individuals born before the first affected child. These recurrence risks were also calculated after stratifying on sex of index case (the oldest affected in this situation) and sex of sibling (or maternal half sibling) and by the number of previously affected siblings (or maternal half siblings). Exact confidence intervals were calculated assuming a binomial distribution.

Because no birth order information was available for paternal half siblings, they were analyzed as a single group. For comparison, population prevalence of ASD was derived from the control sibships by calculating the affected proportion among all siblings of unaffected index subjects. Statistical comparisons of recurrence risks were based on chi-square tests with one degree of freedom.

Interbirth interval has been previously shown to be associated with the risk of ASD in nonfamilial cases, with short intervals increasing the risk (

18). Here, we recalculated the sibling recurrence risks stratified by the number of months since the birth of the previous child.

Multivariate Analysis

To determine the influence of a variety of factors (sex, birth order, parental age, birth weight, interbirth interval, number of prior affected siblings) on recurrence risk, we performed a multivariate analysis of the sequential sibling (and maternal half sibling) recurrence risk data using logistic regression. The dependent variable was always the dichotomous affected status of a sibling (or maternal half sibling). The model covariates were related to the sibling and included sex, birth year, maternal race/ethnicity (white, Asian, African American, Latino), birth weight, birth order (2, 3, or ≥4), maternal and paternal age at birth of child, interbirth interval from previous child (in logarithm months), number of prior affected siblings (0, 1, or 2), number of prior affected female siblings (0, 1, or 2), and birth order of prior affected siblings (1, 2, or 3). The estimates provided are relative recurrence risks, defined as the ratio of recurrence risks for those with different values of the covariate of interest (1 or 0 for the dichotomous variables and per unit value for continuous variables).

In all analyses, birth year, paternal age, and maternal and paternal race/ethnicity and education were not significant; however, birth year was retained in the final model. Birth interval was characterized in logarithm months because of an apparent exponential relationship between interbirth interval and recurrence risk. A p value of 0.05 was used for statistical significance throughout.

In the first multivariate analysis, we included only second-born offspring. In the next analysis, we focused on third-born offspring and added independent covariates representing the affected status of the first two children in the family (first affected, second affected, both affected). In the final analysis, we included all birth orders ≥2 and included birth order and number of previous affected siblings as independent variables for the analysis. Because of sample size, the multivariate analysis of maternal half siblings included all birth orders ≥2, with the same covariates as used in the analysis of full siblings.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the case and control subjects are summarized in

Table 1, along with corresponding values for all California non-ASD births occurring during the same period (

14). Case and control subjects were matched for birth year and location and for maternal age and race/ethnicity. The maternal and paternal ages of case and control subjects were elevated, as expected, compared with the reference population, and Asians were relatively overrepresented and Latinos underrepresented among case and control subjects. Case subjects were slightly more educated than control subjects, and both groups had higher education levels compared with the reference population. In a previous multivariate analysis from this resource (

15), the race/ethnicity and education differences were attenuated and nonsignificant after adjusting for parental age and other covariates.

Recurrence risks to full siblings and maternal half siblings born after affected index cases, stratified by birth order, are listed in

Table 2. A significant birth order effect was observed, where the recurrence risk in second-born siblings was 11.5%, 1.58-fold greater (p<0.0001) than later-born siblings, who had a recurrence risk of 7.3%. There was no difference between third-born and later-born siblings. The recurrence risk among brothers was 14.5%, compared with 5.3% among sisters, and 10.1% for the sexes combined. This is 20-fold greater (p<0.0001) than the prevalence of 0.52% (153/29,384) observed among the siblings of the control index subjects (0.88% for males [134/15,160] and 0.19% for females [19/14,224]).

For maternal half siblings, the recurrence risk was more than twofold greater (p<0.05) for second-born (6.5%) compared with later-born maternal half siblings (2.9%), with no difference between third and later-born half siblings. The overall maternal half sibling recurrence risk across all birth orders was 4.8%, with recurrence risks of 6.3% and 3.2% for the half brothers and half sisters, respectively. Overall, we found a paternal half sibling recurrence risk of 2.3% (7/299; 95% CI=1.2, 6.2), less than half the recurrence risk for maternal half siblings (p<0.05).

Recurrence risk was greater when two previous children in the sibship were affected. For these families, the overall recurrence risk was 23.9%, more than double the recurrence risk when a single prior child was affected (p<0.0001). The recurrence risk was higher (p<0.05) for third-born children (28.9%) compared with later-born children (11.8%), again indicating a birth order effect.

Interbirth Interval

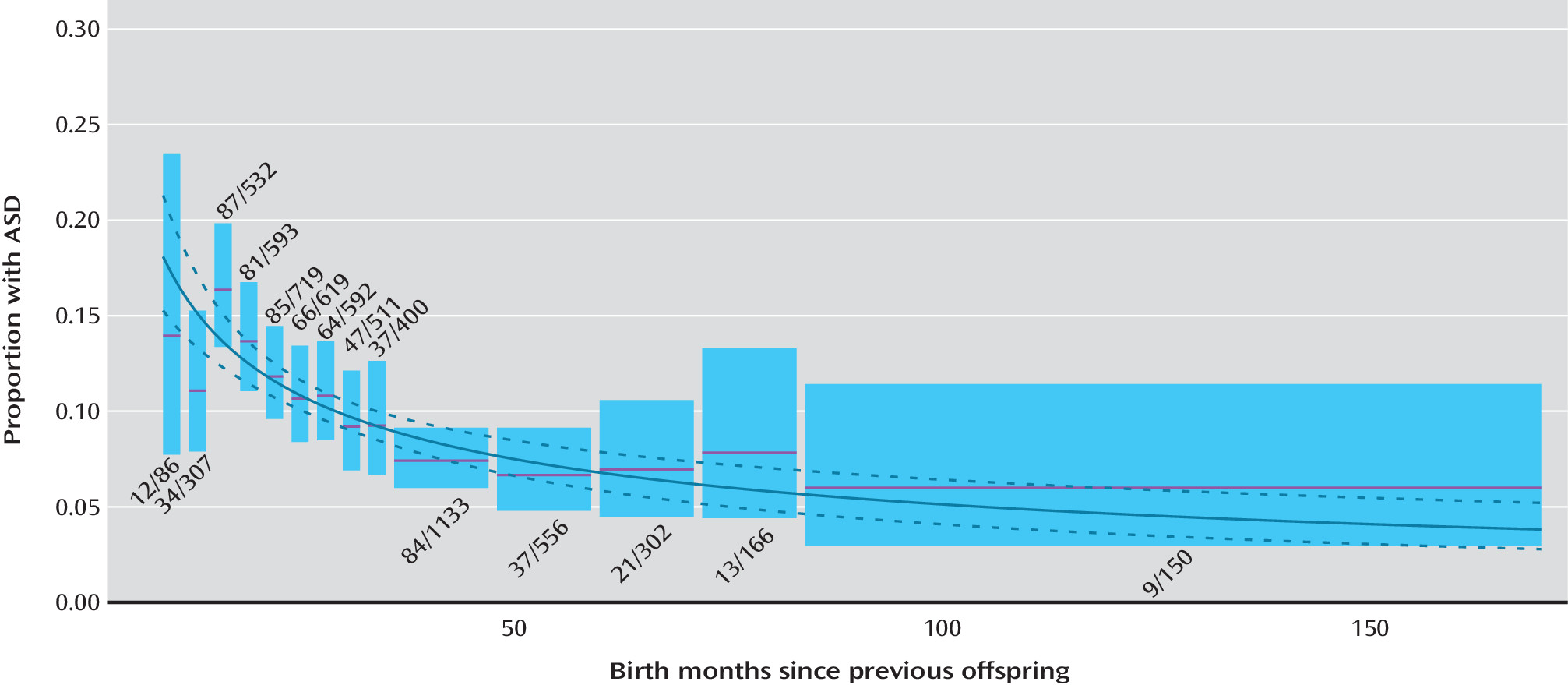

The effect of interbirth interval on ASD recurrence risk is illustrated in

Figure 1. There was a significant increase in ASD recurrence risk with decreasing birth interval. A logistic regression model applied to the data in

Figure 1, where the independent variable was ln(interbirth months), provided an adequate fit to the data and resulted in a highly significant regression coefficient (−0.588, SE=0.088, p<10

−11). For children born within 18 months of the previous child, the recurrence risk was twofold greater than for children born 4 or more years afterward (14.4% [133/925] compared with 6.8% [80/1,164]).

Multivariate Analysis

In the multivariate analysis of second-born children, male sex, previous affected female, higher birth weight, and older maternal age all significantly increased the recurrence risk, and interbirth interval was inversely associated (

Table 3). For third-born children, comparable associations were observed for male sex and interbirth interval but not for birth weight, maternal age, or previous affected female. For this group, having two previous affected siblings significantly increased the recurrence risk. When one previous sibling was affected, the recurrence risk was significantly greater when the previous affected child was second born rather than first born. For all birth orders combined, male sex and maternal age were positively associated and interbirth interval was inversely associated with recurrence risk. Recurrence risk was significantly increased when two or more previous siblings were affected and significantly decreased for siblings of birth orders >2. These results are generally consistent with the univariate analyses of the same variables, with little or no attenuation of effect sizes, so there appeared to be little confounding.

The pattern for maternal half siblings closely mimicked that for full siblings. Recurrence risk increased with male sex, birth weight, maternal age, and female index case, and it decreased with interbirth interval; however, only male sex and interbirth interval were statistically significant. Recurrence risk was significantly increased when two or more previous half siblings were affected, and also decreased for birth orders >2.

Discussion

This study offers a number of strengths. It is population based with high ascertainment of affected individuals; is the largest ever performed in terms of siblings and maternal and paternal half siblings; it incorporates important demographic covariates, such as parental age, race/ethnicity, and education; and it systematically examines recurrence risk while avoiding reproductive stoppage bias. Potential limitations include the lack of structured diagnoses and possible incompleteness in the birth certificate linkage process. In the family linkage, we excluded 53.5% of the originally identified case families. The majority of these exclusions occurred because our study did not capture the oldest children in the sibship (born before 1990) and because of cases that had no siblings or half siblings and hence had no impact on our recurrence risk calculations. Some families were excluded because of ambiguity in relationships. These exclusions were few and were based on quality of matching information from birth certificates; however, such information was unlikely to be differential based on the constellation of affected and unaffected children in the family, as birth certificates (and the information they contain) precede the onset of symptoms. However, as less matching information was available for fathers before 1997, we were not able to produce as large a sample of paternal half siblings as maternal half siblings, so the estimates for paternal half siblings are based on smaller numbers.

As we have noted, the electronic registry diagnoses appear to have high correspondence with conventional research criteria for ASD (

16). However, underascertainment is likely because not all affected children will be receiving services, especially the mildest cases. A previous study estimated that approximately 75% of prevalent ASD cases are found in this registry (

15). Also, there is some concern that follow-up may be less complete for the younger (ages 7–10) compared with the older (ages 11–20) siblings. However, there was no trend toward decreased recurrence risk with birth year, which would have been the hallmark of reduced follow-up. Furthermore, it is also likely that a parent who already had an affected child who was receiving services at a regional center would bring any other affected children to the same center, leading to their ascertainment.

A variety of studies (

5–

13,

18,

19) with different designs have examined recurrence risks for full siblings and maternal and paternal half siblings (

Table 4), and some of these have included reference population prevalences for comparison while others have not. Our result for full siblings is close to the median of previous studies (range, 3.4%−18.7%), as is our population prevalence estimate (0.52%) compared with previous studies (range, 0.04%−2.1%).

Similarly, our recurrence risk for maternal half siblings (4.8%) is close to the median of previous studies (range, 2.0%−7.3%). All studies show a maternal half sibling recurrence risk lower than the corresponding full sibling risk, with a risk ratio ranging from about 0.35 to 0.75 and a median around 0.50, close to our risk ratio of 0.48, strongly supporting a genetic contribution for ASD. By comparison, recurrence risks for paternal half siblings were consistently lower than for maternal half siblings in this study and two previous studies (

8,

10), but still considerably above the population prevalence in this study and one previous study (

8), again supporting genetic heritability.

While the lower recurrence risk for paternal compared with maternal half siblings also provides evidence suggestive of a maternal environmental effect, the variation in recurrence risk by birth order and interbirth interval provides additional support. The recurrence risk for second-born siblings was 1.6-fold higher than for later-born siblings. These results are consistent with a previous study of highly ascertained ASD family collections (

20). Similarly, studies of multiplex ASD sibships suggest that the second affected child is on average more severely affected than the first (

21–

24). Also, our finding that children born within 18 months of the previous child had a twofold greater recurrence risk than siblings born 4 or more years afterward is consistent with two previous independent studies of nonfamilial ASD cases (

18,

25). Notably, the same phenomena regarding interbirth interval and birth order were seen for maternal half siblings, strengthening support for a maternal environment effect. Furthermore, birth order proximity to a previous affected child also matters, as the recurrence risk is greater for a child born right after an affected child compared with children born after an intervening unaffected child.

It is of interest to consider various explanations for these timing-of-birth observations. First, the results could represent a noncausal relationship due to residual confounding (

26). Children with late birth order and long interbirth intervals will tend to be younger and with older parents. Older parents will tend to have a greater risk. On the other hand, younger affected children may not be ascertained if a family migrated out of state. In our regression analysis, the birth order and interbirth interval effects were undiminished after including birth year, maternal age, maternal race/ethnicity, maternal education, sex of child, and family history; the interbirth interval effect was observed for all birth orders, making the timing-of-birth observations less likely to be artifactual. Second, mothers with higher genetic susceptibility may have shorter interbirth intervals. However, this would not explain the observed birth order phenomenon and increased risk to a third-born sibling when the immediately preceding child is affected rather than a child earlier in the birth order. If the birth order and birth-interval effects were paternal in origin, we would have seen an attenuation of the effect sizes in the maternal half siblings compared with the full siblings even in the presence of assortative mating, which we did not.

While likely correlated with maternal environment, the specific factor(s) could be postnatal (such as sibling competition or suboptimal infant breastfeeding) or prenatal (such as maternal nutrition depletion, folate depletion, cervical insufficiency, or vertical transmission of infections) (

27). Short interbirth interval has been associated with other adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth (

28), cerebral palsy (

29), and congenital malformations (

30), as well as with schizophrenia (

31,

32), albeit with more modest impact.

In conclusion, our results support a complex model of familial aggregation involving genetic inheritance that is influenced by maternal effects operating most prominently on second-born offspring and those with short interbirth intervals.