Threat-related attention bias is one of the most consistently demonstrated cognitive correlates of anxiety disorders (

8,

9). Nevertheless, research in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has yielded rather mixed results, with some studies indicating attention bias toward threat (

10–

14) and others showing attention bias away from threat (

12,

15–

19). Importantly, attention bias both toward and away from threat is congruent with two primary symptom clusters of PTSD, namely hypervigilance and avoidance/dissociation (

20,

21), respectively. These inconsistencies in threat-related attention deployment can be viewed as reflecting “instability” in threat monitoring in PTSD patients.

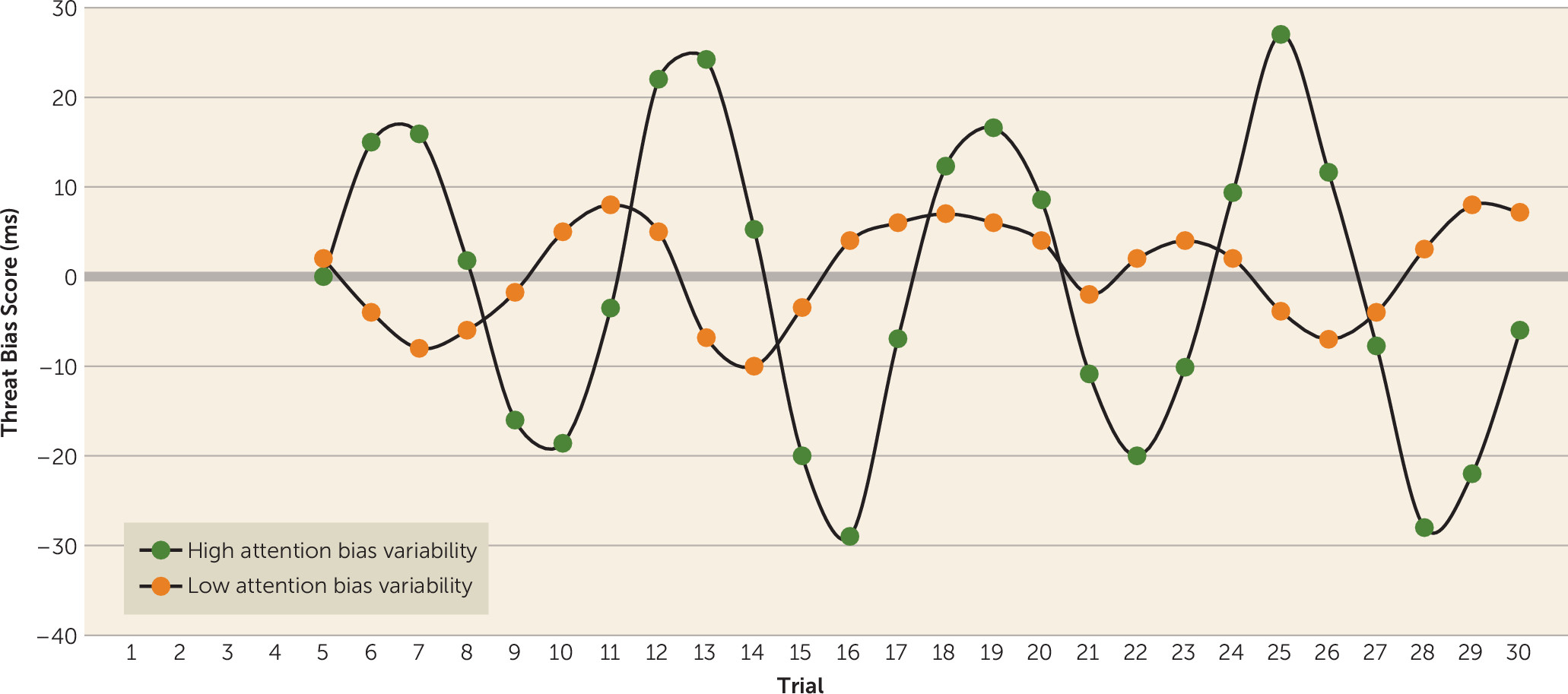

Considering this apparent instability, Iacoviello and colleagues (

22) used a novel approach to quantify threat-related attention biases in PTSD. This approach, termed “attention bias variability,” indexes the degree to which attention fluctuates between vigilance and avoidance and is based on reaction time data derived from variants of the classic dot-probe task (

23). In this task, pairs of threat and neutral stimuli are simultaneously presented across repeated trials. Each stimulus pair is followed by a target probe appearing at the location of either the threat stimulus (congruent trials) or the neutral stimulus (incongruent trials). An attention bias score is calculated as the difference between the mean reaction times of these two types of trials. Typically, a single bias score is calculated by averaging across all the trials presented throughout the measurement session. In contrast, Iacoviello et al. (

22) derived attention bias variability by grouping, or “binning,” consecutive 20-trial sequences on the dot-probe task and calculating a bias score for each bin. The standard deviation of the bias scores across bins was then divided by the participant's mean reaction time to generate the measure of attention bias variability for each subject throughout the session. Results of this study revealed greater attention bias variability in participants with PTSD than in trauma-exposed participants without PTSD and nonexposed healthy participants. Attention bias variability was also positively correlated with PTSD symptom severity. These results suggest that the magnitude of attention bias variability can index the severity of perturbed threat monitoring in PTSD (

22,

24,

25).

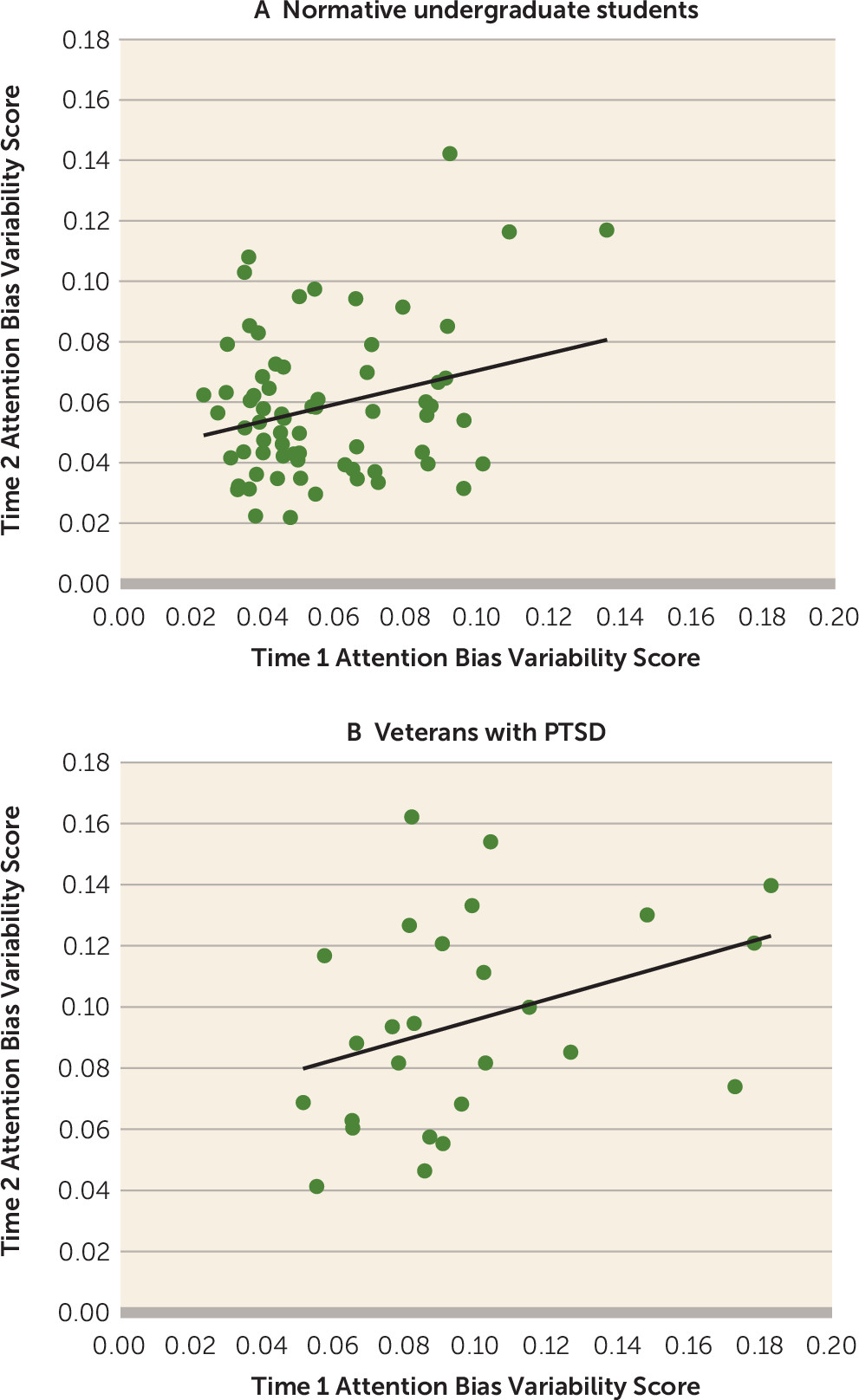

The current report extends this initial study in two ways. First, we refined the measure of attention bias variability by employing a moving average technique, rather than the previously employed binning method, to generate a more stable index that is influenced less by the number of trials in any particular study. Second, through reanalysis of extant data in seven studies that did not previously measure attention bias variability, we probed four questions regarding the relations between attention bias variability and PTSD:

We examined these issues through secondary analyses of samples of Israel Defense Forces combat veterans diagnosed with chronic PTSD, civilian survivors of motor vehicle accidents who were diagnosed with PTSD, deployed Israel Defense Forces soldiers with acute stress disorder following combat exposure, U.S. Army soldiers following deployment to Afghanistan, patients diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, and two samples of undergraduate students. The samples were compared in terms of attention bias variability as calculated by using data from variants of the dot-probe task (described in the Method section).

Discussion

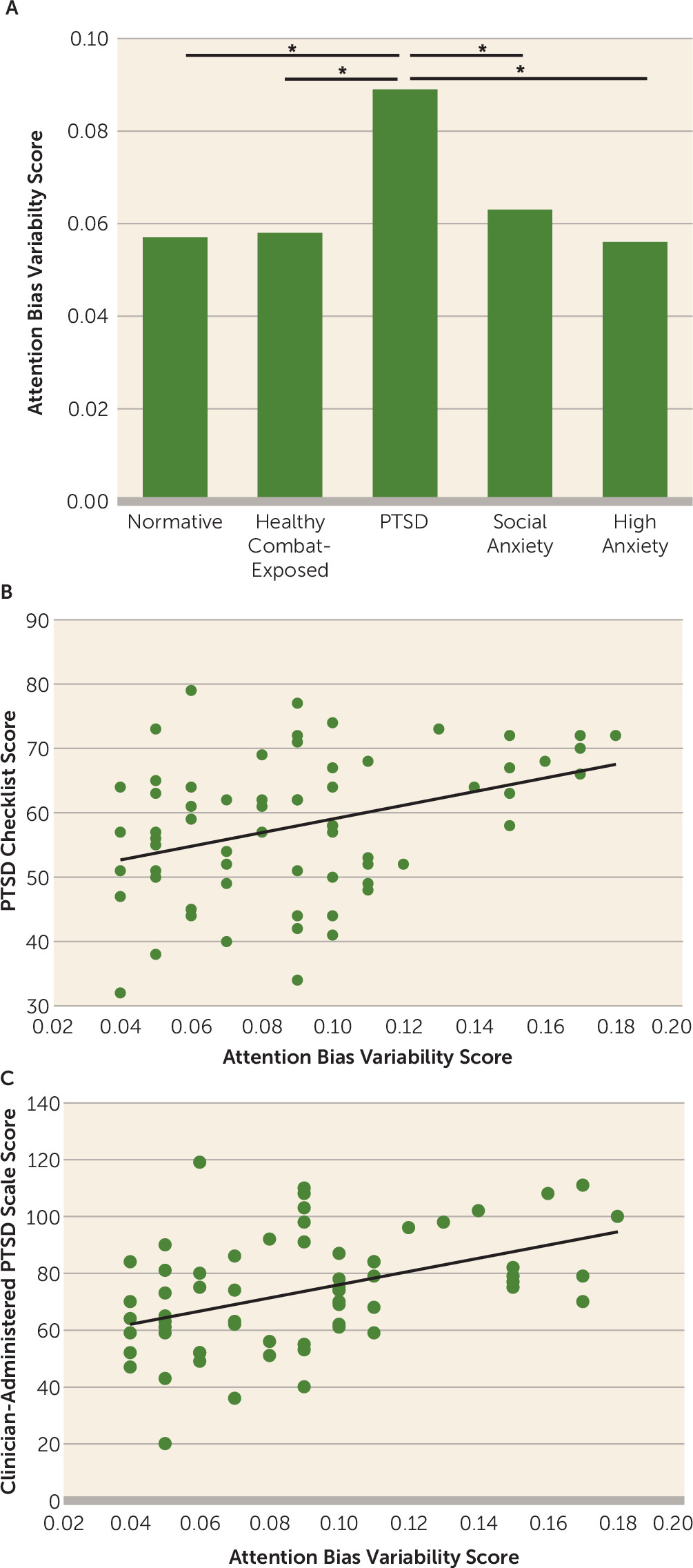

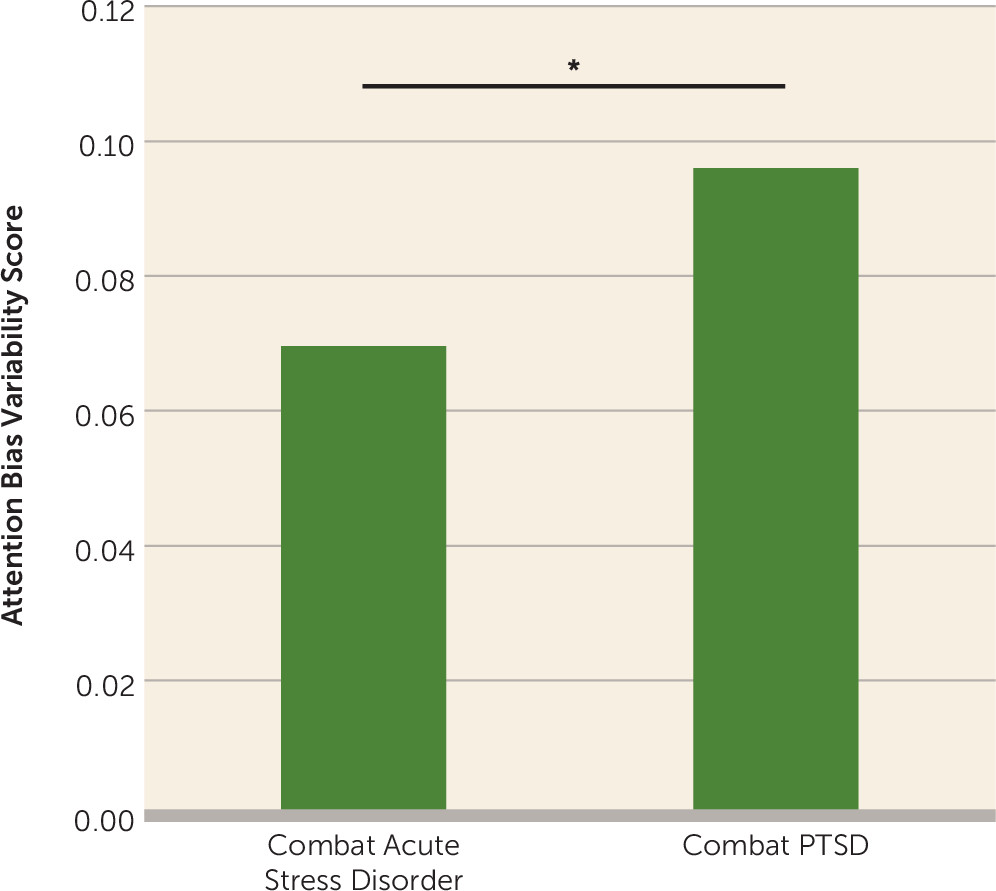

The analyses presented here extend our understanding of attention bias variability and its applicability as a cognitive marker of aberrant attentional processes in PTSD. First, as for the question of whether elevated attention bias variability occurs exclusively in PTSD, analyses revealed elevated attention bias variability in patients with PTSD relative to patients with social anxiety disorder and to undergraduate students with high trait anxiety, with higher attention bias variability associated with greater PTSD symptom severity only in the PTSD samples. Second, similar attention bias variability magnitudes were observed for PTSD caused by different traumatic events. Third, attention bias variability was elevated in veterans with PTSD relative to soldiers with acute stress disorder, with the latter displaying a magnitude of attention bias variability similar to that of the non-PTSD samples. Finally, threat-related attention bias variability, and not positive attention bias variability, was correlated with PTSD severity. These data extend the findings of Iacoviello et al. (

22), who first reported an association between attention bias variability and PTSD, in a number of important ways.

Evidence of greater attention bias variability in individuals with PTSD relative to social anxiety disorder, acute stress disorder, high trait anxiety, and normative samples suggests specificity of elevated attention bias variability in PTSD. Attention bias toward threat occurs in anxiety disorders and among individuals with elevated trait anxiety (

9). In contrast, increased variability between bias toward and away from threat (attention bias variability) occurs only in PTSD, not in social anxiety disorder or acute stress disorder or among individuals with elevated trait anxiety. This could reflect a unique pattern of attention allocation among individuals who manifest persistent PTSD symptoms after a life-threatening traumatic event. On the one hand, confronting a traumatic event may evoke extreme allocation of attentional resources toward threat stimuli in a way that hinders the ability to suppress fear responses, even when the individual is already in a safe context (for instance, see references

36 and

37). On the other hand, traumatic events can induce attentional avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, providing a momentary relief from overwhelming anxiety (see references

18 and

19). These conflicting response patterns, occurring simultaneously during a traumatic event, might challenge the delicate attentional balance normally kept by the human threat-monitoring system.

Indeed, previous studies show that PTSD may involve malfunction of different attentional processes related to fear inhibition (

38,

39) or may involve impaired attention control (

24). A review of executive function in PTSD indicated that attention regulation and response inhibition are among the most robust deficits experienced by patients with PTSD (

24). From this perspective, attention bias variability may reflect the conflict between threat-related attentional hypervigilance and attention suppression, revealed as attention dysregulation. Such perturbations at the attentional level may then be transformed to chronic avoidance and arousal symptoms, appearing concurrently in PTSD. However, in the case of attention bias variability, it is important to underscore the finding that only threat-related attention bias variability, and not positive attention bias variability, was related to PTSD symptom severity, suggesting specificity rather than a more general executive function deficit. Further work examining relations among valence-specific measures of attention bias variability and measures of response inhibition may clarify the factors that produce perturbed attention bias variability in PTSD.

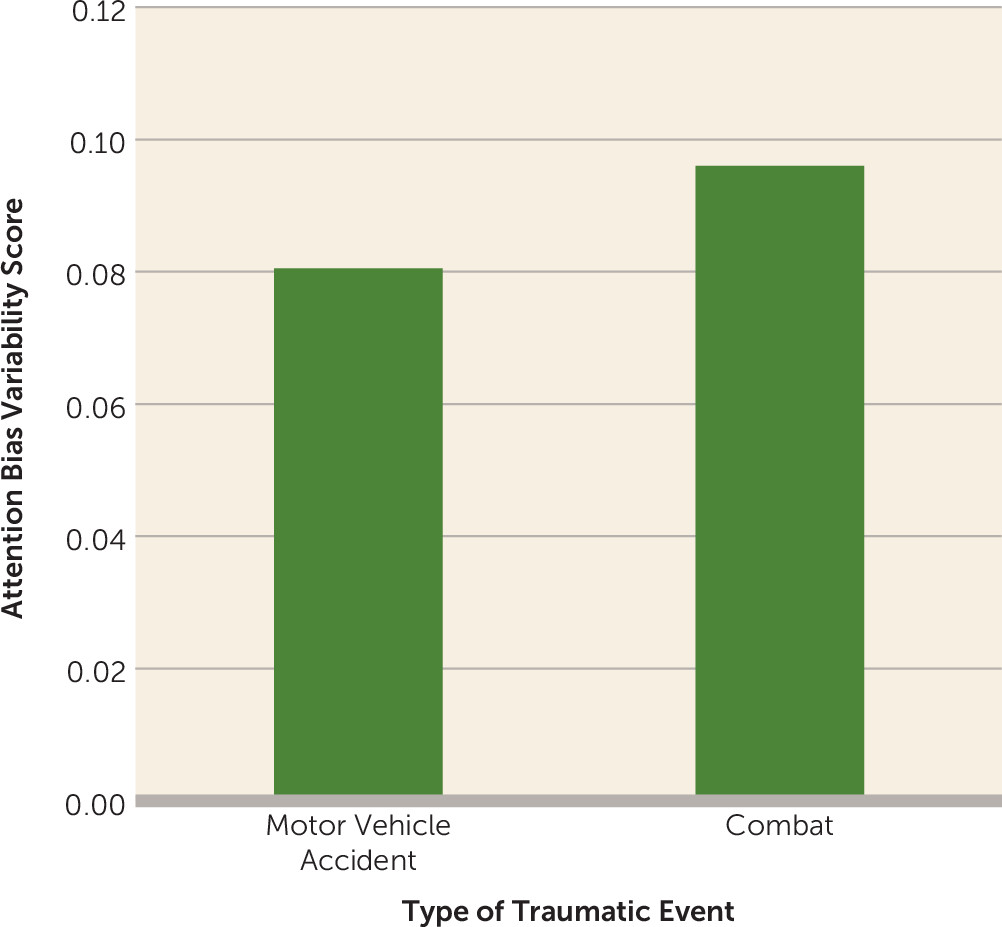

Iacoviello et al. (

22) reported elevated attention bias variability in a combat-related PTSD sample and in an urban civilian population with PTSD not related to combat trauma (e.g., physical assault, accident, witnessing death or violence). The current findings replicated those of elevated attention bias variability in combat-related PTSD in a different sample of soldiers, and they extended the finding of elevated attention bias variability in patients with PTSD after a motor vehicle accident, which is one of the most common events leading to PTSD (

40). Taken together, elevated attention bias variability across different PTSD samples emphasizes the potential value of attention bias variability as a general cognitive marker for PTSD acquired through different types of traumatic contexts.

The current findings also revealed higher attention bias variability in PTSD relative to acute stress disorder. In addition, elevated attention bias variability was associated with trauma-related symptoms in PTSD, but not in acute stress disorder. These results further highlight the specificity of attention bias variability to PTSD, but they also potentially suggest that increased attention bias variability in PTSD develops over time and is related to greater severity and chronicity of symptoms. Stress symptoms typically reside in most people who are exposed to potentially traumatic events. Yet a PTSD diagnosis is made only after a more prolonged period. In the same manner, so are threat-related attention fluctuations that may become more rooted and accentuated with time in certain individuals. Because the majority, but not all, of individuals with acute stress disorder subsequently develop PTSD (

41), more studies are needed to explore the longitudinal trajectory of elevated attention bias variability, possibly by comparing individuals diagnosed with acute stress disorder who eventually develop PTSD to individuals with acute stress disorder who do not develop PTSD by means of a within-between study design. It would also be interesting to test whether attention bias variability is normalized following effective treatment of PTSD.

Finally, the results indicate that the association between attention bias variability and posttraumatic symptoms is specific to threat-related stimuli and is not evident for positive stimuli. These results are in line with theories suggesting increased activation for threat stimuli in PTSD (for example, see reference

42). However, current interpretation of positive attention bias variability findings in PTSD must proceed with caution because of the lack of important comparison groups. There is literature showing that for anxious individuals, attention orienting to positive stimuli is different from that for threat-related stimuli. For threat-related stimuli, only anxious but not healthy individuals show the classic threat bias. For positive stimuli, positive biases seen in healthy individuals are typically attenuated in anxiety (for a review, see reference

43). More studies are needed to further explore the dynamics of positive attention bias variability in PTSD relative to positive attention bias variability in normative and other anxious populations.

The current data also carry implications for recent findings on attention bias modification treatments (

44,

45). Attention bias modification treatments systematically manipulate threat-related attention biases in anxious populations, traditionally targeting a specific attentional bias toward threat in anxiety disorders. Considering the apparent variability of attention biases in patients with PTSD and the lack of clear-cut evidence for an attention bias in a specific direction in PTSD, future studies may consider the development of treatments targeting normalization of attention bias variability instead. Indeed, two recent randomized controlled trials in Israeli and U.S. Armed Forces combat veterans with PTSD indicated that computerized attention control treatment designed to normalize fluctuations in threat-related attention was efficacious in reducing PTSD symptoms and that symptom reduction was mediated by reduction in attention bias variability (

46).

While the neural substrates of attention bias variability are still unknown, studying its neural networks and their perturbed function in PTSD could further highlight potential targets for intervention. Neuroimaging studies in PTSD reveal consistent hyperactivation within limbic regions (particularly the amygdala and insula) and hypoactivation of prefrontal regions, which are involved in enhanced attention toward triggers associated with traumatic material (e.g., the anterior cingulate), and regions thought to be primarily involved in inhibition of responses to emotional stimuli and decreased attention control (e.g., the ventromedial prefrontal cortex) (for reviews and a meta-analysis, see references

47–

49). Perturbations in this neural architecture and the interconnectivity between its different components could serve as preliminary candidates for investigation of the neural underpinnings of elevated attention bias variability in PTSD.

The current report should also be viewed in light of potential limitations. First, the results presented here are based on secondary analyses of samples from different studies; thus, inherently, the samples were not fully matched, and there were subtle differences among the dot-probe tasks employed for the different samples. However, in-depth analyses suggest that these differences in task characteristics did not affect the reported findings. Thus, the current outcomes appear to reflect repeated and robust evidence of elevated attention bias variability in PTSD under diverse traumatic circumstances and populations and when measured with different variants of the dot-probe task, suggesting robustness and generalizability. However, future studies addressing the association between attention bias variability and PTSD through a priori hypotheses and preplanned studies could better control for experimental and population factors in order to provide a better estimate of the actual effect size of the elevated attention bias variability in PTSD.

Second, in the currently analyzed PTSD samples, the stimuli were not specifically tailored to the traumatic event types experienced by the participants. A recent meta-analysis indicates that threat-related attention bias is stronger in PTSD when specific trauma stimuli are used in measurement (

50). Future studies could test whether such content specificity is associated with even more elevated attention bias variability in PTSD patients. Additionally, the current samples differed on stimulus presentation durations. Stimulus presentation times in the dot-probe task could tap into different subcomponents of attention (e.g., capture, disengagement, inhibition of return) and thus could affect the interpretation of the mechanism of attentional fluctuations indexed by attention bias variability. While the current results indicate no differences in attention bias variability and in the pattern of correlation between attention bias variability and PTSD symptoms in two samples whose stimuli were presented for 500 ms (combat PTSD) and 1000 ms (motor vehicle accident PTSD), future studies could manipulate stimulus presentation times and perhaps use alternative paradigms to shed light on this issue.

In conclusion, our findings offer a new perspective on threat-related attention processes in PTSD, suggesting elevated attention bias variability as a marker of this psychopathology. Furthermore, attention bias variability can be easily calculated and offers a new approach to data analysis of attention bias tasks, looking at fluctuations in attention while monitoring threat over time in addition to giving a single read of attention bias directionality. Importantly, attention bias variability could be calculated by using extant dot-probe data in order to address a variety of critical questions related to PTSD as well as other psychopathologies.