Mental disorders are common and represent a significant public health concern (

1). They are associated with a high negative impact on all areas of life and cause more burden of disease than other illnesses (

2). Up to 45% of primary care patients have been found to have at least one mental disorder (

3). Current reviews and practice guidelines regard specific forms of psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT], interpersonal therapy) and specific forms of pharmacotherapy as empirically supported for the treatment of common mental disorders (

4,

5). Psychodynamic therapy, another method of psychotherapy, has a long tradition, and a considerable proportion of therapists report a primary psychodynamic orientation (

6,

7), with some differences between countries.

Thus, the efficacy of psychodynamic therapy is of high relevance to patients, therapists, and the health care system in general. For common mental disorders, evidence for psychodynamic therapy is available (

8). A Cochrane review investigating the efficacy of psychodynamic therapy for common mental disorders found psychodynamic therapy to be superior over control conditions (waiting list, treatment as usual, minimal contact) (

9). In addition, several meta-analyses found no statistically significant differences when psychodynamic therapy was compared with other forms of psychotherapy in patients with anxiety or depressive disorders (

10,

11). Other meta-analyses, however, reported psychodynamic therapy to be inferior to CBT, which is regarded as an established treatment (

12–

14). These inconsistent findings and the frequent use of psychodynamic therapy suggest a need to examine whether psychodynamic therapy is as efficacious as treatments with established efficacy.

A comparison with a rival treatment can be considered a particularly strict test because both specific (e.g., techniques, ingredients, and procedures) and nonspecific (e.g., expectation and attention) factors are controlled for (

15). Comparisons of this kind are rare in the whole field of medicine (

16). Such a test is even more strict if the rival treatment has been established in efficacy. Comparisons for which no differences in outcomes are expected are referred to as equivalence trials (

17,

18). eAppendix A, in the

data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article, highlights the differences between equivalence testing and the far more common superiority testing.

Of note, in psychotherapy research, presently no single individual study seems to exist that is sufficiently powered to test for equivalence if a small margin is used as compatible with equivalence (

8,

19). In contrast, meta-analyses may yield a higher power than individual studies and are therefore especially suitable to test for equivalence; the logic of equivalence testing as outlined in eAppendix A in the

data supplement applies to meta-analyses, as well. Nevertheless, despite available guidelines (

20), equivalence testing in meta-analysis is almost nonexistent.

Applying the procedures of equivalence testing, we investigated whether psychodynamic therapy is equivalent in outcome to treatments established in efficacy for the respective disorder (i.e., other forms of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy).

Method

Study Design and Choice of Equivalence Margin

We conducted the meta-analysis in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (

21). A prespecified protocol is registered at PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; registration number: CRD42016038161).

The design, study selection, and statistical analyses follow the logic of equivalence testing; that is, defining a margin, searching for studies with one or more established comparators, and applying the two one-sided test procedure (

17,

20).

For defining an equivalence margin (i.e., “the minimum difference between two groups that would be important enough to make the two groups nonequivalent” [

20, p. 554]), there are no generally accepted standards. What is considered to be a clinically meaningful minimum difference relative to a clinically irrelevant minimum difference depends on the field of research. If the outcome is a vital event, such as mortality, smaller margins are required than in other fields (

18). Small margins make it more difficult to establish equivalence (

17). As emphasized by Walker and Nowacki, the equivalence margin not only determines the result of the test but also gives scientific credibility to a study: “The value and impact of a study depend on how well the equivalence margin can be justified in terms of relevant evidence and sound clinical considerations” (

17, p. 194).

Several proposals for choosing an equivalence margin in the context of mental disorders have been made (

Table 1). Suggestions for the maximum difference in outcomes considered to be clinically irrelevant range from d=0.24 to d=0.60. The smallest margin was suggested by Cuijpers and colleagues (d=0.24) for the treatment of depression (

22). Thus, for our study across a range of mental disorders, we decided to use a margin of 0.25 (i.e., an equivalence interval of −0.25 to 0.25), corresponding to a small effect size.

Selection Criteria and Search Strategy

Participants were a sufficiently described adult population treated for a specific mental disorder according to DSM-III or later versions or ICD-10 criteria. Organic mental disorders were excluded.

Interventions were manual-guided forms of psychodynamic therapy, a talking therapy operating on an interpretive-supportive continuum (

23). Interpretive interventions focus on conscious and unconscious processes or conflicts and aim at enhancing the patient’s insight in repetitive patterns assumed to sustain his or her problems. Supportive interventions aim to strengthen abilities (“ego functions”) that are (temporarily) not accessible to a patient because of acute stress or because they are not sufficiently developed. Characteristic techniques of psychodynamic psychotherapy include fostering a helpful therapeutic relationship, focusing on affect and expression of emotion, exploring avoidance patterns and resistance to change, identifying recurring themes, discussing past experiences, exploring fantasies and dreams, and focusing on interpersonal issues. Moreover, processes of transference and countertransference are taken into account and interpreted, if suitable (

23,

24).

Comparators were bona fide methods of psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy with efficacy demonstrated for the respective disorder according to published criteria and guidelines (

4,

5,

15). For specific or new treatments not yet included in available listings, we performed our own searches for evidence. Following current standards for a designation as efficacious (

15), we regarded at least two randomized controlled trials carried out in independent research settings as necessary, in which the respective treatment proved to be efficacious.

The primary outcome was “target symptoms,” which included measures specific to the mental disorder under study (e.g., measures of depressive symptoms in depressive disorders or of social anxiety in social anxiety disorder). As secondary outcomes, general psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial functioning (i.e., social, occupational, and personality functioning) were examined. Posttreatment and follow-up assessments were considered.

The meta-analysis included randomized controlled trials in which psychodynamic therapy was compared with a treatment established in efficacy using reliable and valid outcome measures. For intervention and comparison groups, only manual-guided forms of psychotherapy were included. A manual or manual-like guideline is a clear description of a treatment that includes the theoretical background, a set of technical recommendations, and case examples. Concurrent medication was allowed, provided that it was given in all treatment arms. Studies in which psychodynamic therapy was systematically combined with another treatment (e.g., psychodynamic therapy plus pharmacotherapy) were excluded. To ensure effective randomization, a minimum sample size of N=20 patients per treatment group was required for inclusion (

25). Treatments must have been terminated (i.e., no ongoing treatments were permitted).

The following search strategy was applied (the complete search strategy can be found in eAppendix C in the

online data supplement): systematic searches in the electronic databases PubMed, PsycINFO, and CENTRAL; manual searches in relevant systematic reviews, textbooks, and reference lists of included studies; and communication with experts in the field, which included a search in a comprehensive, published, and regularly updated list (the so-called Lilliengren List) of all previously identified randomized controlled trials on psychodynamic therapy (

http://w3.psychology.su.se/staff/peli/RCTs_of_PDT.pdf). No language or date limits were applied. The main electronic search was conducted on March 23, 2016. Updated searches were regularly performed until December 2016.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

After completing literature searches, all hits (N=5,142) were saved in the citation management program EndNote. After removal of duplicates (N=1,216), two authors (C.S., F.L.) independently screened titles and abstracts of the remaining 3,926 articles according to the predefined selection criteria. All potentially relevant articles were then retrieved for full-text review (N=62), which resulted in the inclusion of 23 randomized controlled trials (and a total of 30 articles, of which seven presented follow-up data or additional outcomes; see

Table 2 and eAppendixes B and D in the

online data supplement). To retrieve study details, a data extraction form was used. Effect sizes included in the main analysis (i.e., target symptoms at posttreatment) were independently extracted and calculated by two authors each. To determine interrater reliability for the calculation of effect sizes, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated with SPSS, version 23 (SPSS, Chicago), using a two-way mixed model in combination with the absolute agreement type, single measures. Interrater reliability proved to be excellent (ICC=0.99). Disagreements in the search process and effect size calculation were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third expert. Masking of raters regarding authors of primary studies was not done because evidence suggests that such masking is unnecessary for meta-analyses (

26).

Assessment of Study Quality

Study quality was assessed by use of the Randomized Controlled Trial Psychotherapy Quality Rating Scale (RCT-PQRS) (

27). The RCT-PQRS provides an empirical method for evaluating the quality of published randomized controlled trials. It contains 24 items rated on a scale from 0 to 2, yielding a maximum score of 48. A quality score of 24 or above is considered to represent a cutoff for a “reasonably well done study” (

28, p. 24). The RCT-PQRS was found to have good interrater reliability, internal consistency, and validity (

27). RCT-PQRS ratings for each study were performed by at least two independent raters. Interrater agreement for the total score was excellent (ICC=0.82). The average total score of the respective independent ratings was used in the statistical analyses.

Assessment of Allegiance

It has been repeatedly shown that results in psychotherapy research might be heavily biased by researchers’ allegiances (

29,

30). Despite these findings, allegiance is rarely controlled for both in primary studies as well as in meta-analyses (

31). We took allegiance into account on both levels.

First, to control for possible allegiance effects and to minimize bias on the level of performing this meta-analysis, a model of adversarial collaboration was implemented by including proponents of both psychodynamic therapy (C.S., F.L., and T.M.) and CBT (J.H. and S.R.), the treatment psychodynamic therapy was compared with most often in the present meta-analysis (k=21/23). J.H. is a CBT researcher, and S.R. is a specialist in research methods and research synthesis who, although putting special emphasis on research of psychodynamic therapy, has been formally trained in CBT.

Second, researcher allegiances often find expression in design features such as poor implementation of unfavored treatments or uncontrolled therapist allegiance (

29,

32). To assess allegiance on the level of included studies, we modified a scale used in a previous study by one of us (T.M.) (

29). The scale consists of five items assessing allegiance on four levels (the complete scale can be found in eAppendix E in the

online data supplement): researcher allegiance (two items), therapist allegiance, trainer allegiance, and supervisor allegiance.

Items were assessed separately for each treatment condition based on the information provided in the respective articles. For each condition, scores were added, and the difference in scores between the conditions was calculated. The scale yields a score from 0 (balanced allegiance) to 4 or −4 (strong allegiance toward one treatment). Each study was judged by two independent raters. Interrater agreement was excellent (ICC=0.83). Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, version 3. We aggregated effect size estimates across studies, adopting a random effects model, using maximum likelihood estimation to estimate between-study variability (tau

2). Between-group effect sizes for psychodynamic therapy compared with established comparators were calculated for the primary outcome (target symptoms) as well as for two other outcome areas: general psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial functioning. A complete list of assessed outcomes and assignment of outcomes to outcome areas can be found in eAppendix F in the

data supplement. Whenever possible, we used the most basic effect size estimate (i.e., unadjusted values). For continuous outcomes, Hedges’ g correcting for small sample bias was determined by calculating the difference of the mean scores of the respective treatments at posttreatment or at follow-up and dividing it by the pooled standard deviation. If means and standard deviations were not reported or could not be calculated, we used dichotomous data (e.g., remission or response). When continuous and categorical data of the same outcome instrument were provided, only the continuous data were included to avoid redundancies. Whenever a study reported data of more than one outcome instrument for an area of outcome (e.g., target symptoms), we assessed effect sizes separately for each instrument and calculated a combined effect to assess the overall outcome. In case continuous and dichotomous data were available, they were transformed into a common metric (Hedges’ g). When means and standard deviations or dichotomous data to calculate effect sizes were not provided, we contacted the authors of relevant studies (k=1). In case a study included more than two comparison groups, we included pairwise comparisons separately. To avoid “double counts” in the shared intervention group, the shared group N was split in half (

33). Assessments at the end of treatment and at the latest follow-up were included. Intent-to-treat data were preferred over completer data. All effect sizes were coded in such a way that a positive sign indicated an advantage of psychodynamic therapy.

To test equivalence, we applied the two one-sided test procedure (see also eAppendix A in the

online data supplement) (

17,

20) using a prespecified equivalence interval of −0.25 to 0.25 at a significance level of 0.05 for each of the two one-sided tests (

17). Corresponding to the two one-sided tests, a 90% equivalence confidence interval (CI) was calculated according to ES ± (z

α)×(SE), with ES being the mean pooled effects size, SE the standard error of ES, and z

α=1.645 (

20). If the CI is included in the prespecified equivalence interval, the null hypothesis of nonequivalence is rejected and equivalence is concluded (

20). Here, a significant result indicates equivalence.

Heterogeneity was assessed by chi-square heterogeneity tests and I2 statistics. The I2 statistic expresses the ratio of true to observed variance with values of 25%, 50%, and 75%, referred to as low, moderate, or high heterogeneity, respectively. Publication bias was assessed by testing for funnel plot asymmetry and by means of the Duval and Tweedie trim and fill procedure.

Moderator analyses were performed for a range of variables by means of meta-regressions using maximum likelihood estimation. The following moderators were studied: year of publication, recruitment method (community compared with clinical compared with mixed), intent-to-treat compared with completer analyses, type of diagnosis, study quality (total score of the RCT-PQRS), allegiance, number of sessions in the psychodynamic therapy groups, patient-per-therapist ratio (as an indicator for bias from therapist effects), and average sample size per group to investigate the presence of small study bias (

34).

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

Literature searches yielded 23 randomized controlled trials, published between 1983 and 2016, that fulfilled the a priori set selection criteria (

Table 2). These studies included data on 2,751 patients. Twenty-one randomized controlled trials compared one or more forms of psychodynamic therapy with another form of psychotherapy, which in all cases was a method of CBT. Comparisons with other forms of psychotherapy, such as interpersonal therapy, were not identified. The remaining two studies compared psychodynamic therapy with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or with a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor in the treatment of depression. The majority of studies (k=8) investigated participants with a depressive disorder, followed by anxiety disorders (k=4), eating disorders (k=4), personality disorders (k=4), substance dependence (k=2), and posttraumatic stress disorder (k=1). With one exception (an investigation studying group psychotherapy), all studies employed psychodynamic therapy in an individual face-to-face format.

Equivalence Testing: Psychodynamic Therapy Relative to Established Comparators

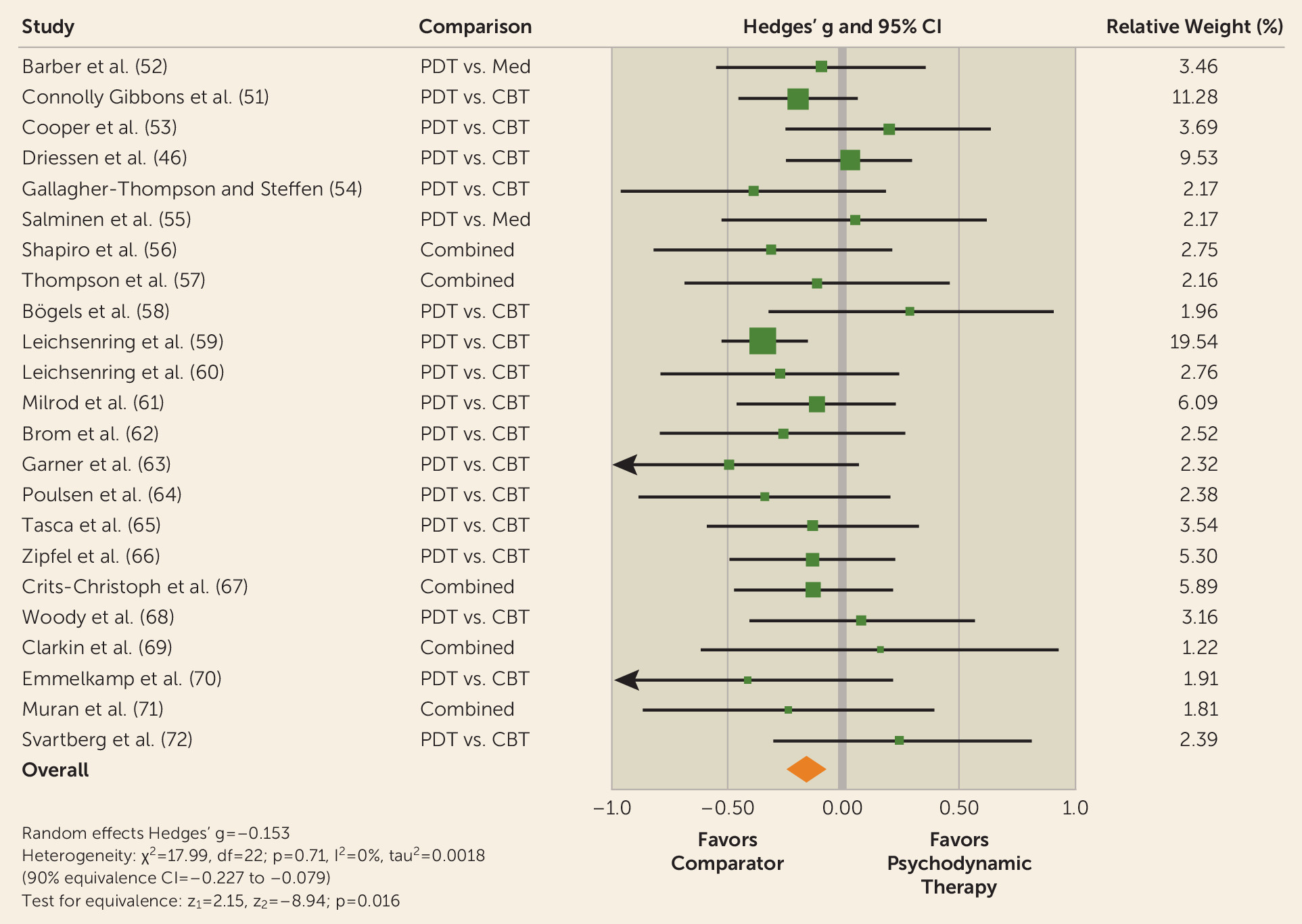

The pooled between-group difference in outcome for target symptoms at posttreatment was g=−0.153, indicating a small difference in favor of comparison treatments (

Figure 1,

Table 3). The 90% equivalence CI for this contrast was −0.227 to −0.079. Because this CI was included in the prespecified equivalence interval (−0.25 to 0.25), the null hypothesis of nonequivalence was rejected, and the alternative hypothesis of equivalence was accepted (p=0.016). Heterogeneity was very low (I

2=0, tau

2=0.0018). Similar results were found for target symptoms at follow-up (k=16, pooled difference g=−0.049, 90% equivalence CI=−0.137 to 0.039, p=0.0001; I

2=7.12, tau

2=0).

Equivalence was also shown for the other areas of outcome at posttreatment and follow-up (

Table 3), except for psychosocial functioning. For the latter, psychodynamic therapy was not statistically equivalent to comparison treatments but was nominally better (g=0.165, 90% equivalence CI=−0.027 to 0.358, I

2=57.59), suggesting superiority of psychodynamic therapy. However, a post hoc test of superiority did not yield statistical significance (p=0.162). Excluding randomized controlled trials in which the comparison condition consisted of pharmacotherapy (k=2) did not change results, implying equivalence in outcome of psychodynamic therapy and CBT (

Table 3).

Study Quality and Allegiance

Results for study quality and allegiance ratings can be found in

Table 2. With a mean score of 35.3 (SD=5.7), the vast majority of studies (k=21/23, or 91%) clearly were above the RCT-PQRS cutoff score of 24. For two studies with scores of 22, quality was below the RCT-PQRS cutoff.

Most of the studies achieved a balanced allegiance score of 0 (k=16); that is, no indicators for a favor toward one of the tested treatments were found. In k=7 of included studies, we found a minor allegiance toward the comparison treatment (score of −1 [k=6] or −2 [k=1]), while we found a minor allegiance toward psychodynamic therapy in k=4 studies (score of 1). Thus, in cases where some indication of allegiance was found, it was only minor (i.e., only one or two of four indicators were positive).

Moderator Analyses

According to moderator analyses performed for the main analysis (target symptoms at posttreatment), no moderator was significantly related to outcome (p>0.19, see

Table 4), implying, for example, that the results are valid across the various disorders (no effect of diagnosis).

Publication Bias

Egger’s regression test did not indicate funnel plot asymmetry (intercept=0.67, 95% CI=−0.39 to 1.73, p=0.20). Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure indicated two missing studies on the left of the mean (i.e., in favor of comparisons). Adjusting for publication bias resulted in the addition of two “trimmed” studies and an adjusted pooled effect size of g=−0.176. However, this did not change the main result as the 90% equivalence CI (−0.246 to −0.106) was included in the equivalence interval (p=0.04). To assess equivalence after correcting for publication bias, the standard error (SE) was obtained via the following formula: SE=(upper limit−lower limit)/3.92=0.043 (

33).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first in psychotherapy research to systematically investigate equivalence of a specific form of psychotherapy to established treatments by formally applying the logic of equivalence testing. Our meta-analysis found psychodynamic therapy to be as efficacious as other treatments with established efficacy, including CBT. Because we used high methodological standards (e.g., controlling for researcher allegiance, applying the logic of equivalence testing, using one of the smallest margins ever suggested as compatible with equivalence, and using treatments established in efficacy as comparators), the results of this meta-analysis can be expected to be robust. However, the number of studies that could be included is still limited, and further research is required.

Several conventional meta-analyses reported no differences in outcome between psychodynamic therapy and other treatments (e.g.,

10,

11), whereas other conventional meta-analyses reported CBT to be superior to psychodynamic therapy (

12–

14). It is of note, however, that these previous meta-analyses did not apply the logic of equivalence testing, did not include only established comparators, and did not adequately control for researcher allegiance, thus allowing only for less definite conclusions. Our results are consistent with the conventional meta-analyses that reported no differences in outcome between psychodynamic therapy and other treatments (

10,

11), adding more robust data to support the notion of equivalence between treatments. It is of note that the meta-analyses reporting inferiority of psychodynamic therapy showed both some differences in design and several methodological shortcomings (

35). For example, Tolin (

13) applied less strict inclusion criteria than our meta-analysis did, which resulted in the inclusion of 11 randomized controlled trials that did not fulfill our inclusion criteria. Thus, the overlap in studies between Tolin’s and our meta-analysis is small (k=7). Furthermore, according to Tolin’s own analysis, most of the results in favor of CBT compared with psychodynamic therapy were not robust against file drawer effects (

13). The two further meta-analyses that found CBT to be superior to psychodynamic therapy are both based on only three studies of psychodynamic therapy and are therefore not representative (

12,

14). Further shortcomings of these meta-analyses were discussed by Wampold et al. (

35).

Our findings are limited with regard to psychopharmacology because only two studies of this treatment were included. Previous meta-analyses concluded that psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy may be equally efficacious (

36), suggesting that this may also be true for psychodynamic therapy regarding the mental disorders studied here. Furthermore, randomized controlled trials comparing psychodynamic therapy with other forms of psychotherapy, such as interpersonal therapy, were not identified. Like all meta-analyses, the present one is limited by the nature of the studies included. To the extent that some of the studies comparing psychodynamic therapy with CBT or with medication may have recruited, at least in part, patients who do not respond well to treatment, the literature may be biased toward the finding of no differences between these treatments. However, the between-studies variance was very low, suggesting no significant effects of low responsiveness.

Although efficacious treatments for mental disorders are available, it is important to note that, in general, rates of response and remission are not yet satisfactory. For anxiety disorders, for example, a recent review found a mean CBT response rate of 49.5% (

37). For depressive disorders, response rates are comparable, but remission rates are even lower (

38). Thus, at present, none of the available treatments may claim to be the panacea. There clearly is room for improvement. Because therapist effects seem to have a stronger impact on outcome than the treatments being compared and need to be taken into account, one promising strategy for improving treatments is enhancing therapist training and eventually therapist outcome (

39). Furthermore, different patients may benefit from different approaches, which is why a shift from one empirically supported treatment to another may be helpful in case of nonresponse (

40,

41).