An estimated 13%–20% of U.S. troops returning from Iraq and Afghanistan may have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (

1), and an estimated 30% of Vietnam-era veterans have lifetime PTSD (

2). In randomized trials, trauma-focused cognitive processing therapy, prolonged exposure, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing have demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements in patients with military-related PTSD (

3–

7). However, a recent review found that despite strong within-group improvements from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy (Cohen’s d values, 0.78–1.10), approximately two-thirds of study subjects with military-related PTSD still met criteria for PTSD, and many retained clinically significant symptoms at posttreatment assessment (

5). Some complementary therapies for PTSD have been developed, but the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) has noted that past trials have had methodological weaknesses, such as small sample sizes and a lack of active controls (

8).

The mantram repetition program has been found to mitigate PTSD symptoms and other psychological distress and to improve quality of life in a variety of populations (

9). The program teaches people to intentionally slow down thoughts and to practice “one-pointed attention” by silently repeating a personalized (self-selected)

mantram, a word or phrase with a spiritual meaning (

10). The technique is easily used, and practice can be done inconspicuously. Mantram practice is initially recommended during nonstressful times and nightly before sleep to elicit the relaxation response, develop mindful attention (

11), and reduce sleep disturbances (

12). Later it is used during, and in anticipation of, triggering events or intrusive imagery to regulate emotions and to calm behavior (

13).

Mantram therapy may be a valuable addition to current PTSD treatments because it incorporates some components of evidence-based treatments, yet without the trauma focus that can deter some clients. Quantitative and qualitative studies of mantram therapy delivered as a group intervention in veterans have shown significant efficacy in reducing posttraumatic stress symptom severity (

13,

14), managing sleep disturbances (

12), increasing mindfulness (

13), and increasing levels of self-efficacy for managing PTSD symptoms (

15).

Here, we report on the first randomized controlled trial of individually delivered mantram therapy compared with present-centered therapy. Present-centered therapy is a supportive, problem-solving, non-trauma-focused treatment for PTSD that has been shown to be clearly superior to a waiting list control condition (effect sizes ranging from 0.74 to 1.27) (

16), and it has been used as an active control for trials of prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy (

16–

18). Our primary hypothesis was that mantram therapy would produce greater improvements in PTSD symptoms than present-centered therapy, as measured by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (

19) and the PTSD Checklist–Military (PCL-M) (

20). Our secondary hypotheses were that mantram therapy would produce greater reductions in the severity of symptoms frequently associated with PTSD—insomnia, depression, and anger—and greater improvements in spiritual well-being, mindfulness, and quality of life.

Method

Design

A two-arm, two-site randomized trial was conducted at the San Diego and Bedford, Mass., Veterans Affairs Medical Centers from January 2, 2012, through March 31, 2014. Institutional review boards at both sites approved the study. All participants provided written informed consent and were randomly assigned to treatment arms by study coordinators using sealed lists of computer-generated random numbers from the study statistician. Participants taking and not taking medications prescribed for PTSD were randomized in separate blocks. The study used open allocation (participants were informed of assignment at randomization) but blinded assessment before treatment, after treatment (week 9), and at 2-month follow-up (week 17).

Participants

Self-selected treatment-seeking Veterans Health Administration patients were recruited through flyers and provider referrals. Participants were at least 18 years of age and had endorsed at least one traumatic experience related to military service. All met DSM-IV-TR criteria for PTSD, and all met symptom severity cut-off scores of ≥45 on the CAPS and ≥50 on the PCL-M. Participants who were taking medications for PTSD had been on a stable dosage (ascertained by chart review and self-report) for at least the previous 6 weeks and were instructed to continue taking their medications as prescribed. Participants were asked to refrain from receiving other psychotherapy or complementary therapy during the study.

Procedures

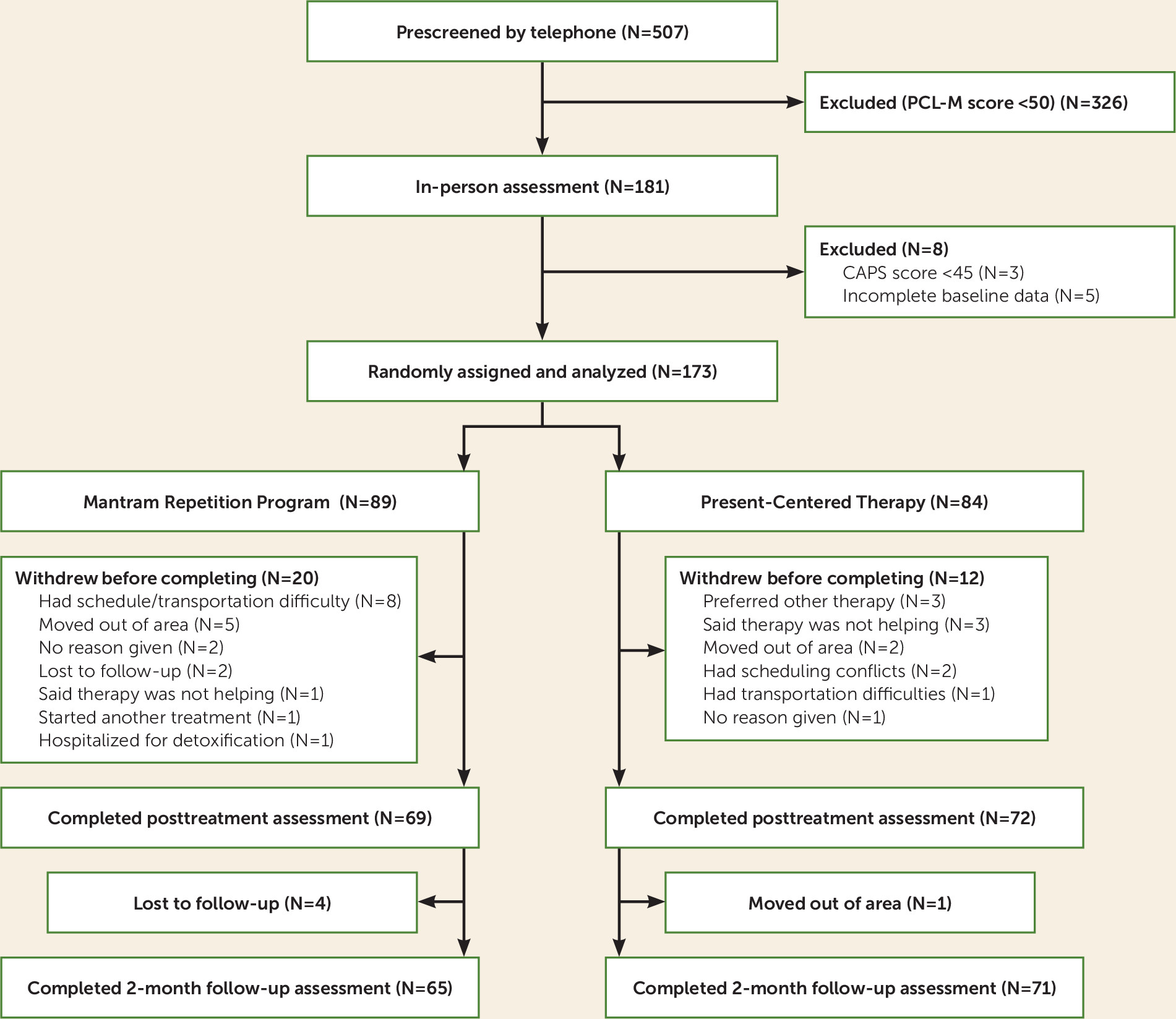

All participants were initially screened by telephone. Those with PCL-M scores >50 were invited for an in-person assessment. Consenting participants received the CAPS interview and completed clinical measures and demographic and medication questionnaires, and if they met the study criteria, they were enrolled prior to randomization.

Portions of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview were used to exclude individuals with severe suicidal ideation, dementia, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, or untreated bipolar disorder. Participants were also excluded if they scored <25 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (

21), ≥ 3 (for women) or ≥4 (for men) on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test consumption items (

22), or ≥6 on the Drug Abuse Screening Test or if they had practiced complementary therapies (e.g., mindfulness or meditation, self-hypnosis, biofeedback, yoga, tai chi) within the past 6 months. A data monitoring committee assessed the study for safety and recruitment.

Primary Outcome Measures

CAPS scores can range from zero to 136, with higher scores indicating greater severity (

19). A reduction of ≥10 points is considered a clinically meaningful improvement (

17). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91. CAPS assessors had at least a master’s degree or equivalent and underwent training to competence with the CAPS senior trainer. A random sample of audio-recorded CAPS interviews was reviewed by the senior trainer and two assessors for interrater reliability. Mean intraclass correlations between raters were 0.99 for total score and 0.99, 0.99, and 0.98 for subscales for criteria B, C, and D, respectively.

Self-reported PTSD symptoms were assessed using the 17-item PCL-M (scores can range from 17 to 85, with higher scores indicating greater severity). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Insomnia symptoms were measured using the seven-item Insomnia Severity Index (scores can range from 0 to 28, with higher scores indicating greater severity; a score ≥11 traditionally indicates clinically significant insomnia) (

23). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

Depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (scores can range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating greater severity) (

24). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86.

Anger was measured using the State-Trait Anger Inventory–Short Form (

25) (scores can range from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater severity) on each of two subscales, state anger and trait anger. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96 for state anger and 0.89 for trait anger.

Spiritual well-being was measured using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-Being questionnaire (scores can range from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating greater spiritual well-being) (

26). Sample items include “I feel peaceful” and “I have a reason for living.” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86.

Mindfulness was measured using the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (scores can range from 39 to 195, with higher scores indicating greater mindfulness) (

27). A representative item is “I find myself doing things without paying attention.” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89.

Quality of life was assessed using the World Health Organization Quality of Life brief form (scores can range from 0 to 130; scores of 60 or more indicate higher quality of life) (

28). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Frequency of mantram practice (adherence to one of three skills taught in the mantram program) was measured using self-reported mantram sessions (a session was defined as repeating a mantram at least once) at the posttreatment and follow-up assessments (see Appendix 1 in the online supplement).

Treatment Conditions

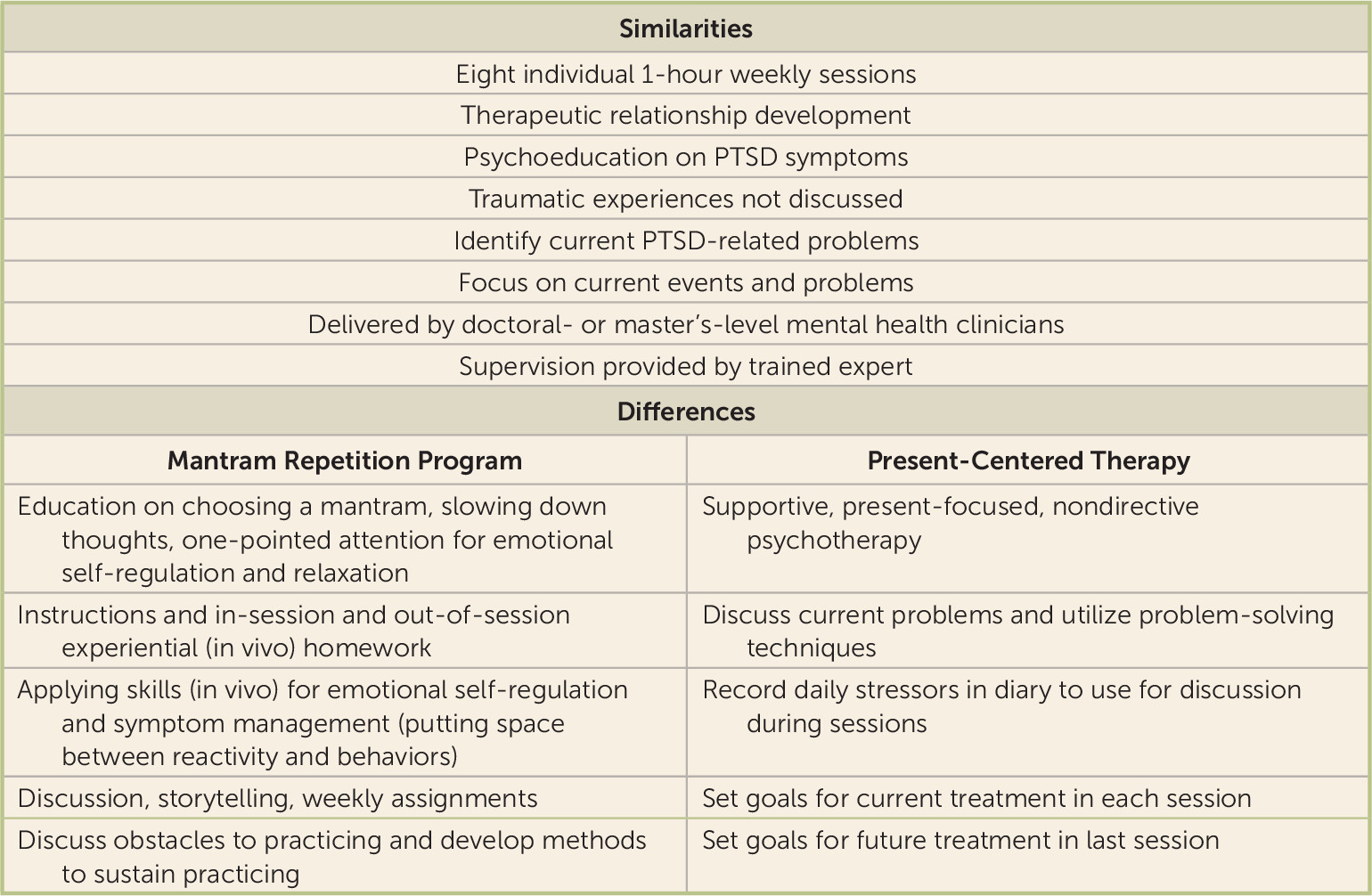

Both treatments were delivered one-on-one in eight weekly 1-hour sessions, using standardized manuals and instructor guides (

Figure 1). Mantram therapy and present-centered therapy facilitators each facilitated only one treatment type. Facilitators completed 2-day trainings with role-plays and supervision in their respective treatments and received biweekly supervision (from J.E.B., senior mantram therapy expert, or Melissa Wattenberg, who contributed to the development of present-centered therapy).

Mantram Repetition Program

Mantram therapy is based on the premise that silently repeating a mantram (a spiritually related word or phrase selected by each individual from a recommended list) enables users to train attention, initiate relaxation, and become aware of the present moment. This skill, along with two others that are taught—“slowing down” and “one-pointed attention”—has been shown to reduce stress and increase emotional self-regulation (

13–

17). Participants were encouraged to practice all three skills as often as possible to interrupt stressful thoughts, feelings, or behaviors and ultimately to manage symptoms such as hyperarousal, anger, irritability, insomnia, flashbacks, and numbing/avoidance.

Present-Centered Therapy

Present-centered therapy is a manualized, supportive, present-focused psychotherapy with demonstrated efficacy for PTSD that has been used as an active comparator in other PTSD trials (

18). It focuses on current events and uses techniques such as mirroring participants’ experiences and problem-solving to assist patients in dealing with current stressors. Participants are given a daily diary to record stressors to discuss with their therapists in a supportive, nondirective manner, using problem-solving techniques.

Treatment Fidelity, Credibility, and Expectancy

All treatment sessions were audio-recorded, and 15% were rated by a content expert not involved in treatment delivery using a content checklist (

29). Overall, 94% of mantram therapy and 88% of present-centered therapy content items were completed. Treatment credibility and expectancy were assessed at baseline and after treatment using the Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (

30) (see Appendix 2 in the

online supplement).

Data Analysis

To provide 80% power to detect a medium-sized effect for the CAPS at an alpha of 0.05, the target sample size was estimated conservatively at 150 participants per treatment arm (by assuming that outcomes were measured just once after baseline, rather than twice). Interim analyses were not conducted, but the study ended before this sample size was attained because of funding constraints (final N=173). Baseline sociodemographic variables were summarized using means for quantitative variables and proportions for categorical variables. For all outcomes, we computed means and confidence intervals.

The primary analyses compared change in PTSD severity using CAPS and PCL-M scores at the posttreatment and 2-month follow-up assessments. Linear mixed models, using PROC MIXED in the SAS statistical package (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.), including random intercepts, were fitted to measurements available at each time point to test whether within-subject changes in outcome variables differed by treatment condition at the posttreatment and 2-month follow-up assessments. To reduce the impact of any residual imbalances in patient characteristics, we included all baseline variables in our model, along with study site, assessment time point as a three-level categorical variable, study arm, and the interaction of assessment time with study arm. Time effects were assumed to follow an autoregressive structure to account for time dependence. Effect sizes were computed as Cohen’s d (

31). The p values resulting from all primary analyses and a priori secondary analyses accounted for test multiplicity using a false discovery rate adjustment (

32,

33).

Two benchmarks of residual PTSD severity were evaluated post hoc by separately examining participants who 1) no longer met PTSD criteria according to the frequency−1/intensity−2 rule for the CAPS, which is used to determine whether symptom severity is still sufficient to fulfill diagnostic criteria for PTSD (

19), and 2) demonstrated a clinically meaningful improvement of ≥10 points in CAPS score (

17).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted, using linear mixed models and false discovery rate adjustment (

32,

33), to examine the change in outcome in specific subsets of the “as randomized” sample. The posttreatment sensitivity analyses were restricted to those individuals for whom both baseline and posttreatment assessments were available for a particular measure; similarly, the 17-week follow-up sensitivity analyses examined only those participants who contributed data at all three assessments (see Appendix 3 in the

online supplement).

Discussion

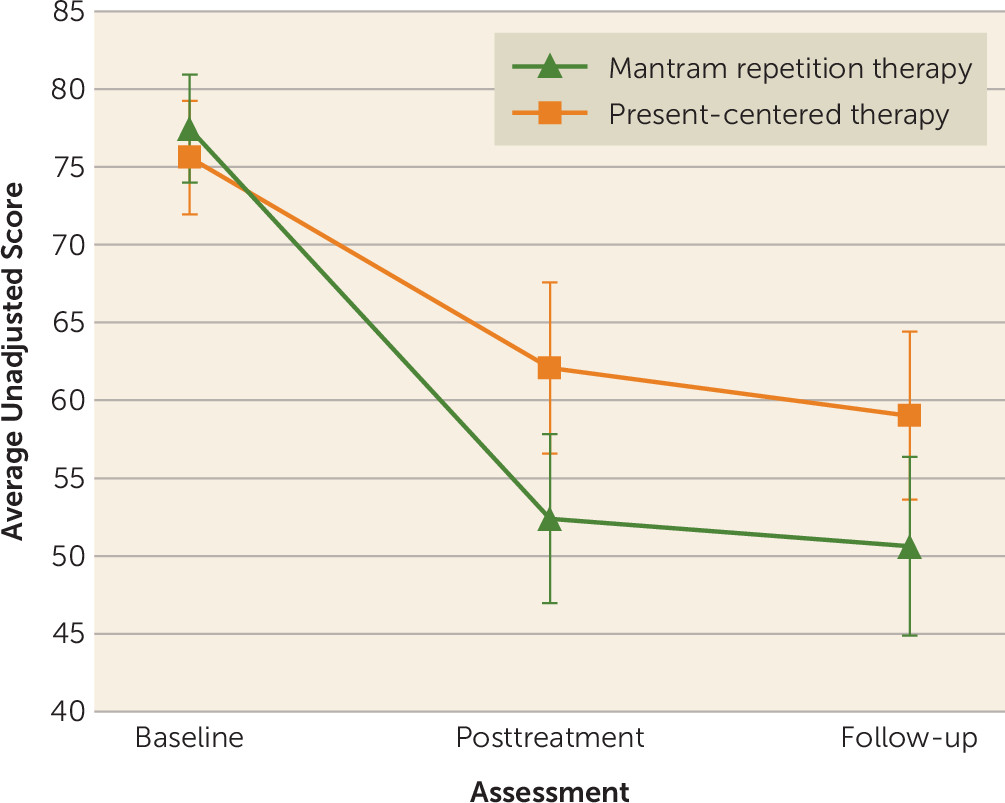

In this randomized trial of 173 veterans receiving non-trauma-focused interventions, mantram repetition therapy was associated with greater reductions in the clinician-rated primary outcome measure (the CAPS) at the posttreatment and 2-month follow-up assessments than present-centered therapy, with a moderate effect size at both time points. Mantram therapy was also associated with greater reductions in self-reported PTSD symptom severity (on the PCL-M) at the posttreatment assessment but not at the 2-month follow-up assessment. More mantram participants no longer met criteria for a PTSD diagnosis at the 2-month follow-up. The proportion of participants with a reduction of ≥10 points in CAPS score did not differ between treatment arms. Finally, mantram therapy was associated with moderate effect-size reductions in insomnia at both time points.

This is the first randomized trial to demonstrate the efficacy of mantram therapy delivered individually compared with an active comparison treatment. Mantram therapy delivered individually appears to be more effective than the group format used in previous studies (

12–

14). This finding is consistent with a meta-analysis showing that, for veterans, group-only formats tend to perform worse than individual treatment formats for PTSD treatment (

34).

This trial’s design addressed frequent criticisms of complementary therapy research, including the absence of an active comparison arm to control for nonspecific effects of therapy. Our findings add to the literature showing that non-trauma-focused therapies for PTSD can yield substantial improvements in PTSD symptoms (

16,

35). Mantram therapy is also briefer than some other PTSD psychotherapies, and we observed a 78% retention rate during active mantram treatment. Previous studies suggest that mantram therapy may help individuals with PTSD by reducing reactivity and initiating relaxation (

14). Mantram therapy also includes a spiritual component; however, we observed no significant differences in the total scores of our spirituality or mindfulness measures when mantram therapy was compared with present-centered therapy, which suggests that mantram therapy’s benefits in this trial may stem from other aspects of the treatment.

Study strengths included clinician-blinded ratings of PTSD using a gold-standard assessment measure (the CAPS), patient-reported ratings of PTSD using a psychometrically strong questionnaire, clinically important secondary analyses (anger, quality of life, and insomnia—sleep problems are among the top reasons returning troops seek PTSD treatment) (

36), adjustment for multiple comparisons for both the primary and secondary outcome analyses, stratification of our randomization by medication use for PTSD, the inclusion of covariates in the linear mixed models to address even modest imbalances in baseline characteristics, collection of data concerning treatment credibility/expectancy and frequency of mantram practice, and treatments of equal length (eight sessions) and therapist time (1-hour sessions) using standardized guidelines. In fact, because slightly fewer participants completed mantram therapy than present-centered therapy, average total time spent with a therapist would be expected to be slightly greater for the present-centered therapy group.

Study limitations include a smaller sample size than our original goal, self-report ratings for some endpoints (e.g., insomnia), the possibility that participants had received prolonged exposure or other trauma-focused therapy prior to enrollment, the lack of a measure of therapist alliance, and assessment of outcomes at only two postrandomization time points. Thus, inferences concerning longer-term improvements in PTSD symptoms cannot be made. Our assessment of fidelity (only 15% of treatment sessions, reviewed by a single rater) was also limited compared with some other studies, and fidelity was slightly greater for mantram therapy content (94%) than for present-centered therapy content (88%). Our data on mantram practice were collected in the last week of treatment (see Appendix 1 in the online supplement) and were restricted to subsets of participants who completed treatment and completed the study; future research might more intensively investigate practice frequency over time and examine how mantram practice is related to outcomes.

Because our study did not have a waiting list control condition, it is not possible to exclude the possibility that, even though present-centered therapy has an evidence base as an effective treatment for PTSD (

16), it might have been delivered in this study in a manner that unintentionally provided less effective PTSD symptom relief. We sought to minimize this possibility by using facilitators who exclusively delivered present-centered therapy and who received supervision from a present-centered therapy expert. However, while present-centered therapy has been found in multiple trials to be superior to a waiting list condition, these studies have examined present-centered therapy delivered over longer periods than the eight 1-hour session format used here (

37,

38). Present-centered therapy participants in our trial did experience a posttreatment improvement in CAPS score (mean decrease, 13.5 points; see

Table 2). However, this change is less than the 20.5- to 22.2-point decreases in CAPS score observed in trials where present-centered therapy was demonstrated to be superior to a waiting list control condition (

37,

38) and the 15.2- to 17.8-point decreases in CAPS score observed for present-centered therapy when it was used as an active comparator in studies of cognitive processing therapy or prolonged exposure (

18,

39).

Few trials have identical attrition between study arms, and while our attrition was not significantly different between treatments, attrition during treatment was somewhat greater in the mantram group (22%) than in the present-centered therapy group (14%). Our linear mixed models used only data on participants who completed treatment, which was all the data available in the study, so if individuals who responded less well to treatment were more likely to stop treatment, this may have biased results to an uncertain extent in favor of mantram therapy. Based on expressed reasons for study noncompletion (see

Figure 2), it did not appear that more participants were dropping out of mantram therapy for a lack of treatment response (e.g., only one individual, compared with three in the present-centered therapy arm, cited “lack of treatment response”). Baseline CAPS scores for those who did not complete mantram therapy were significantly higher than for those who did.

While the study included an active control condition, it did not compare mantram therapy with cognitive processing therapy or prolonged exposure, two evidence-based psychotherapies currently used by the Veterans Health Administration for PTSD treatment. The effect size for the baseline-to-posttreatment change in CAPS for the 8-week course of mantram therapy compared with present-centered therapy examined in this trial (d=0.49) is generally similar to or greater than the effect sizes observed for prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy when compared with present-centered therapy (see Appendix 5 in the online supplement). However, there are a number of differences between our trial and those trials (see above and Appendix 5), including the duration of present-centered therapy treatment delivered and different participant populations (e.g., the participant groups for those other studies were predominantly female). It would be premature to draw any conclusions about the efficacy of mantram therapy compared with these established treatments, or other treatments, without head-to-head trials.

Finally, our veteran sample was self-selected, reported limited substance abuse, and was drawn from only two centers, located in the East and West Coast areas of the United States. The study findings may not generalize to different veteran samples, nonmilitary samples, or other geographical locations where religious and cultural beliefs may differ. In the future, studies of broader patient samples or varying designs could be considered (see Appendix 6 in the online supplement).