Emotion Dysregulation in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Abstract

Method

Results

Prevalence

Childhood.

| Study | Participants | Definition of “Emotion Dysregulation” | Impairment Criterion | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children and adolescents | ||||

| Stringaris and Goodman (51) | Population based; N=5326 | Parent and self-report of emotional lability | Severity ratings of symptoms occurring “a lot” | Parent rating of impairing emotional lability: ADHD alone, 38% (RRR=12 compared with unaffected); ODD alone, 42% (RRR=14.7); self-report: ADHD alone, 27% (RRR=6.9); ODD alone, 14% (RRR=3.0) |

| Sobanski et al. (52) | Family based; ADHD, N=216; siblings, N=142 | Conners emotional lability index, parent and teacher ratings of unpredictable mood changes, temper tantrums; tearfulness; low frustration tolerance | 3 SD above population norms | 25% of ADHD probands had emotional lability >3 SD above population norms |

| Anastopoulos et al. (53) | Family based; ADHD, N=216; siblings, N=142 | Conners emotional lability index (see above) | Above 65th percentile of population norms | Elevated levels: ADHD, 47%; unaffected, 15% |

| Spencer et al. (54) | Clinic based; ADHD, N=197; controls, N=224 | Parent report of “dysregulation profile” based on Child Behavior Checklist subscales of attention problems, anxiety/depression, and aggression | Scores 1–2 SD above norms (above 2 SD, considered bipolar phenotype and excluded) | ADHD, 44% with dysregulation profile; controls, 2% |

| Sjöwall et al. (35) | Clinic based; ADHD, N=102; controls, N=102 | Parent report of child’s ability to regulate specific emotions | Not given | ADHD showed significant impairment compared with controls in regulating all emotions |

| Strine et al. (55) | Population based; history of ADHD, N=512; no history of ADHD, N=8,169 | Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire, parent report of emotional and conduct problems, including: often loses temper, often unhappy (also clingy, fearful, somatic complaints, and having worries) | Parent rating of each symptom’s impact | Emotional problems: history of ADHD, 23%; no history of ADHD, 6.3% |

| Becker et al. (56) | Clinic based; ADHD, N=1,450 | Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire, parent report of emotional problems (see above) | Based on U.K. population norms | 40% of boys and 49% of girls had abnormally high levels of emotional problems |

| Adult studies | ||||

| Able et al. (57) | Population based (N=21,000); diagnosed ADHD, N=198; likely ADHD (based on self-report scale), N=752; controls, N=199 | Self-report of tendency to become angry, disagree, or be critical of others; self-report of degree to which others evoke feelings of anger | Not given | Both diagnosed and likely ADHD subjects more likely to express anger, to engage in conflict, and to have been the target of anger or intimidating behavior |

| Barkley and Fischer (58) | Clinic based; ADHD, N=55; controls, N=75 | Self-report of items reflecting emotional impulsivity (taken from the Behavior Rating of Executive Functioning) | Symptom occurs “often” | Impatient: ADHD, 72%; controls, 3%; quick to anger: ADHD, 65%; controls, 6%; easily frustrated: ADHD, 85%; controls, 7%; emotionally overexcitable: ADHD, 70%; controls, 6%; easily excitable: ADHD, 73%; controls, 14% |

| Reimherr et al. (59) | Clinic based; ADHD, N=536 (enrolled in treatment trials) | Self-report of items from the Wender-Reimherr Adult Attention Disorder Rating Scale: irritability and outbursts; short, unpredictable mood shifts; emotional overreactivity | 2 SD above population norms | 32% met criteria for emotion dysregulation |

| Reimherr et al. (60) | Clinic based; ADHD, N=47 (enrolled in treatment trial) | Wender-Reimherr Adult Attention Disorder Rating Scale (see above) | 2 SD above population norms | 78% met criteria for emotion dysregulation |

| Surman et al. (61) | Clinic based; ADHD, N=206; controls, N=123 | Barkley’s self-report scale: quick to anger, loses temper, argumentative, angry; easily frustrated, touchy; overreactive emotionally, easily excited | Above 95th percentile on population norms | Met criteria for emotion dysregulation: ADHD, 55%; controls, 3% |

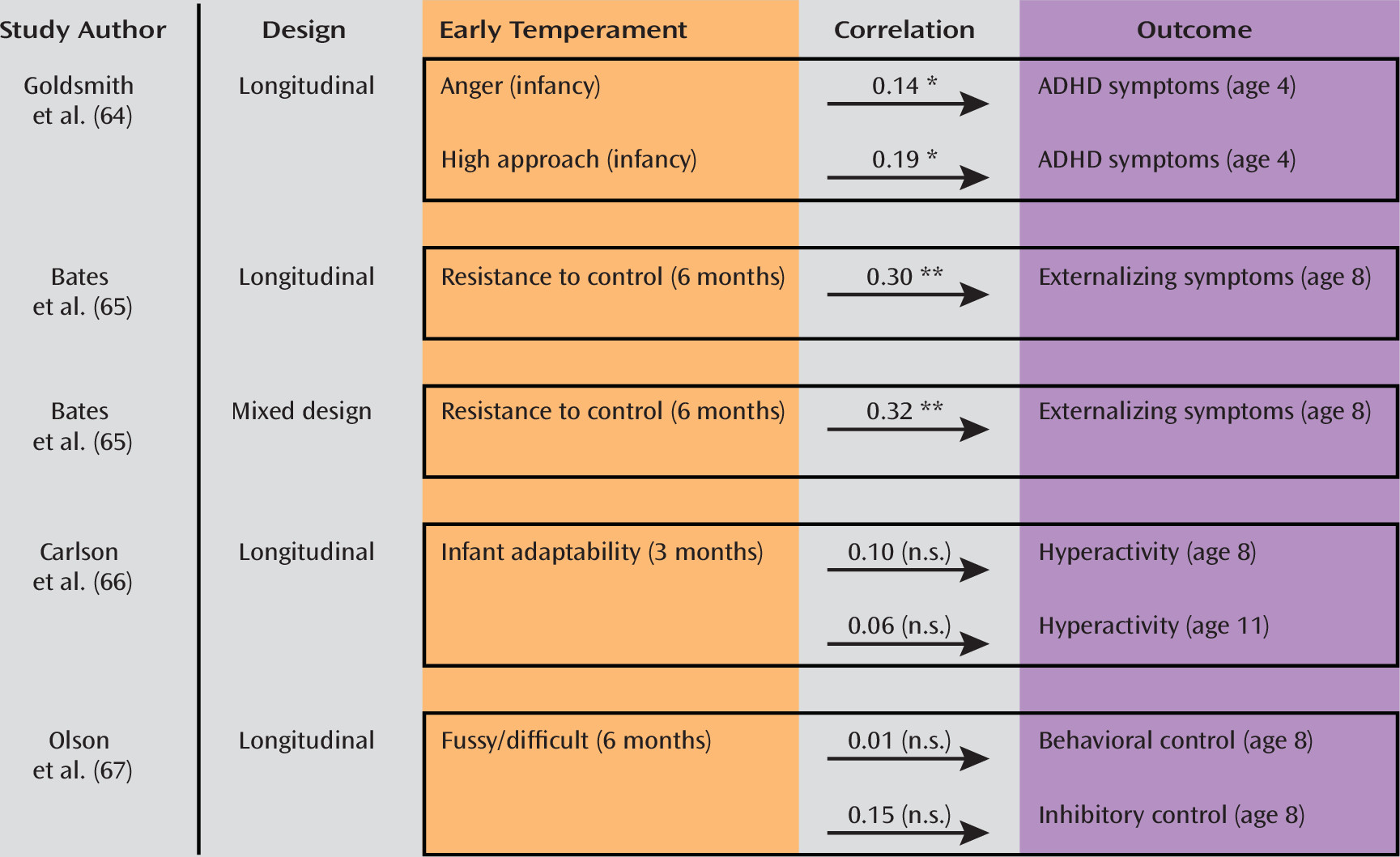

Infancy and early childhood.

Longitudinal studies.

Adult studies.

Impairment.

Pathophysiology

| Study | Participants | Task | Behavioral results | fMRI results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion perception and recognition | ||||

| Brotman et al. (79) | ADHD with no comorbidity, N=18; severe mood dysregulation, N=29 (24 with ADHD); bipolar affective disorder, N=43 (20 with ADHD); healthy, N=37 | Rating of fear, nose width, and passive viewing of neutral, fearful, happy, and angry faces | Rating of fear in neutral faces: severe mood dysregulation = bipolar > healthy; ADHD did not differ from any group | Left amygdala activity during fear ratings: ADHD > healthy = bipolar > severe mood dysregulation |

| Marsh et al. (80) | ADHD with no comorbidity, N=12; callous-unemotional traits, N=12; healthy, N=12 | Gender judgments on fearful, neutral, and angry faces | No group differences in accuracy; ADHD had slower reaction times | Amygdala activity in ADHD during fear processing did not differ from healthy |

| Posner et al. (81) | ADHD, N=15 (mix of medication naive and receiving psychostimulants; some had ODD, although the number is unclear); healthy, N=15 | Subliminal presentation of fearful face followed by supraliminal presentation of neutral expression on the same face; postscan face memory test | No group differences | Greater activity in medication-naive ADHD in amygdala and stronger functional connectivity with lateral prefrontal cortex (BA47) |

| Herpertz et al. (24) | ADHD without comorbidity, N=13; conduct disorder, N=22 (16 with ADHD); healthy, N=22 | Passive viewing of negative, positive, and neutral scenes | Subjects with conduct disorder rated emotional pictures as less arousing than did other groups | Increased left amygdala activation in conduct disorder with ADHD, not ADHD alone; ADHD alone had decreased insula activation to negative faces |

| Schlochtermeier et al. (82) | Adults treated in childhood for ADHD with no comorbidity, N=10; adults with childhood ADHD, medication naive, N=10; healthy, N=10 | Rating of positive and negative pictures | Adults with ADHD treated in childhood rated neutral pictures as more pleasant than medication naive and healthy subjects | Decreased ventral striatum and subgenual cingulate activation in medication-naive adults with history of ADHD; ADHD treated in childhood did not differ from healthy |

| Malisza et al. (29) | ADHD, N=9; autism, N=9; healthy, N=9 | View happy and angry faces and respond to happy | Accuracy: autism < ADHD = healthy | ADHD had less fusiform, temporal poles activity than healthy; ADHD showed same amygdala activity as healthy; autism showed less amygdala activity than other two groups |

| Reward processing | ||||

| Ströhle et al. (83) | Adult ADHD without comorbidity, N=10; controls, N=10 | Monetary incentive delay | No group differences | Decreased ventral striatum activation in ADHD during reward anticipation, and increased orbitofrontal activation during reward receipt |

| Plichta et al. (38) | Adult ADHD without comorbidity, N=14; controls, N=12 | Delayed discounting task (choose between immediate small and delayed large rewards) | No group differences | Decreased ventral striatum activation in ADHD during processing of both immediate and delayed rewards; within subjects, delayed reward in ADHD associated with increased activity of amygdala and caudate |

| Scheres et al. (84) | Adolescent ADHD, N=11; controls, N=11 | Monetary incentive delay | No group differences | Decreased ventral striatal activity in ADHD during reward anticipation |

| Stoy et al. (85) | Adult ADHD, N=24 (analyzed as remitted versus persistent, and as history of childhood treatment with psychostimulants versus medication naive); controls, N=12 | Monetary incentive delay | No group differences | Decreased insula activation during outcome of loss avoidance in medication-naive adults compared with other groups |

| Rubia et al. (86) | Childhood ADHD on and off psychostimulants, N=13 (1 with comorbid ODD); healthy, N=13 | Rewarded continuous performance task | No difference between medicated ADHD and healthy; trend to worse performance in unmedicated ADHD | Unmedicated ADHD showed orbitofrontal hyperactivation during reward receipt, normalized by psychostimulants |

| Control of attention to emotional stimuli | ||||

| Passarotti et al. (87) | Adolescent ADHD without comorbidity (N=14); bipolar disorder, N=23; healthy, N=19 | Working memory task using angry, happy, and neutral faces | Accuracy: healthy > ADHD > bipolar | ADHD compared with healthy: decreased prefrontal and striatal activation to angry faces, increased to happy; ADHD compared with bipolar: similar cortical anomalies, more prominent subcortical anomalies in bipolar |

| Passarotti et al. (88) | Adolescent ADHD without comorbidity (N=15); bipolar disorder, N=17; healthy, N=15 | Emotional Stroop test | Bipolar and ADHD slower than healthy; more interference from positive distractors in bipolar and from negative distractors in ADHD | For negative versus neutral words: gradient of ventrolateral prefrontal cortical activation: ADHD < healthy < bipolar; both ADHD and bipolar showed more dorsolateral prefrontal and parietal activation than healthy |

| Posner et al. (89) | Adolescent ADHD, on and off psychostimulants, N=15; healthy, N=15 | Emotional Stroop test | Medication-free ADHD showed medial prefrontal hyperactivity with positive and hypoactivity with negative distractors; normalized on psychostimulants | |

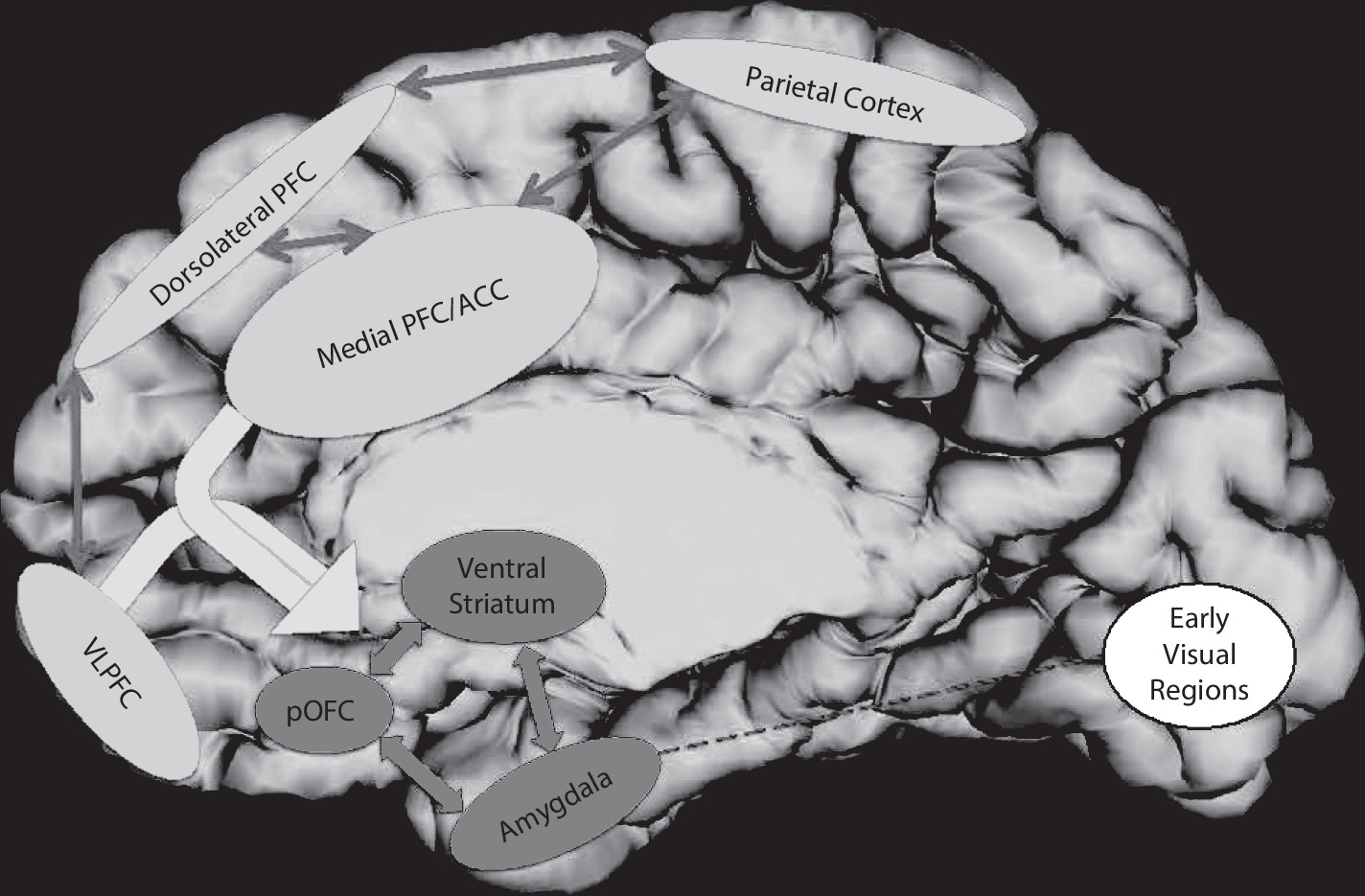

Bottom-up psychological mechanisms.

Top-down regulatory processes.

Neural mechanisms.

Etiological factors.

Treatment

| Study | Participants | Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children | |||

| Childress et al. (117) | Lisdexamphetamine versus placebo for 4 weeks, N=283; at baseline 179 had prominent emotional lability | Conners Parent Rating Scale of emotional lability (angry/resentful, losing temper, and irritability); prominent emotional lability defined as having at least one symptom “pretty much” or “very much” | For those with prominent emotional lability, medication was associated with a significant reduction in emotional symptoms; no change in emotionality seen in those with low emotional lability |

| Ahmann et al. (118) | Crossover design; treated with placebo or low-dosage (0.3 mg/kg) and higher-dosage (0.5 mg/kg) methylphenidate; N=234 | Side effect questionnaire including items on dysthymia, euphoria, irritability, and anxiety | Decreased irritability on methylphenidate (odds ratio=0.33, 95% CI=0.18–0.61) |

| Gillberg et al. (119) | Amphetamine versus placebo for 6 months, N=56 | Side effect questionnaire including items on dysthymia, euphoria, irritability, and anxiety | No differences between treated and placebo groups |

| Kratochvil et al. (120) | Atomoxetine versus placebo, for 8 weeks, N=179 | Emotion and Expression Scale for Children | No difference between atomoxetine and placebo |

| Coghill et al. (121) | Crossover methylphenidate 0.3 mg/kg and 0.6 mg/kg versus placebo for 12 weeks, N=75 | Conners’ emotional lability subscale | Significant reduction in emotional lability for both low-dosage (parent-report effect size, 0.46; teacher-report effect size, 0.45) and high-dosage methylphenidate (parent-report effect size, 0.42; teacher-report effect size, 0.79) |

| Herbert et al. (122) | Randomized to waiting list or parent training to boost child’s emotion regulation and socialization, N=31 | Emotion Regulation Checklist | Parent training linked with moderate reduction of child’s emotional lability (effect size, 0.27–0.45). |

| Webster-Stratton et al. (123) | Randomized to waiting list or parenting program boosting positive and consistent parenting style, N=99 | Emotion regulation scale | Moderate effect of intervention on emotion regulation (effect size, 0.25) |

| Adults | |||

| Reimherr et al. (60) | Crossover trial of extended-release methylphenidate versus placebo (4 weeks each arm), N=47 | Wender-Reimherr adult ADHD scale, emotion dysregulation items | Decrease in emotion dysregulation on methylphenidate (effect size, 0.7) |

| Reimherr et al. (59) | Post hoc analyses of trials comparing atomoxetine and placebo; ADHD only, N=359; ADHD and emotion dysregulation, N=170 | Wender-Reimherr adult ADHD scale, emotion dysregulation items | Decrease in emotion dysregulation on atomoxetine (effect size, 0.66) |

| Marchant et al. (124) | Crossover trial of transdermal methylphenidate versus placebo (4 weeks each arm); ADHD alone, N=21; ADHD and emotion dysregulation, N=28; ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder, N=9; ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and emotion dysregulation, N=32 | Wender-Reimherr adult ADHD scale, emotion dysregulation items | All groups showed benefit on psychostimulants; trend for those with emotion dysregulation to improve most |

| Rösler et al. (125) | Methylphenidate versus placebo with 24-week double-blind phase, N=363 | Wender-Reimherr adult ADHD scale, emotion dysregulation items | Methylphenidate reduced emotional lability (effect size, 0.28–0.4) |

| Emilsson et al. (126) | Cognitive behavioral therapy and medication versus medication alone, N=54 | Self-report scale of emotional control | Combination group did not show significantly better emotional control at end of intervention but did 3 months following intervention (d=1.12) |

Conceptual Models

| Phenomenology | Pathophysiology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Correlations Between ADHD and Emotion Dysregulation | Clinical Course | Psychological Basis | Neural Basis | Genetic | Treatment |

| Emotion dysregulation is integral to ADHD | Extremely high | Yoked clinical courses for symptoms of ADHD and emotion dysregulation | Deficits in behavioral inhibition and working memory mediate both core ADHD symptoms and emotion dysregulation | Anomalies confined to fronto-striatal-cerebellar circuits | Same genetic basis for ADHD with emotion dysregulation and ADHD alone | Treatments that improve ADHD will improve emotion dysregulation |

| Combined ADHD and emotion dysregulation defines a distinct entity | ADHD subgroup exists that is high on both symptom domains | Distinct clinical course for ADHD with emotion dysregulation and ADHD alone | Distinct cognitive deficits in ADHD with emotion dysregulation and ADHD alone | Distinct neural bases for ADHD with emotion dysregulation and ADHD alone | Distinct genetic bases for ADHD with emotion dysregulation and ADHD alone | Existing treatments for ADHD may be less effective for ADHD with emotion dysregulation |

| Symptoms of ADHD and emotion dysregulation are correlated but distinct dimensions | Modest | Similar but dissociable clinical courses for symptoms of ADHD and emotion dysregulation | Deficits in emotion processing mediate dysregulation and correlate with deficits mediating core ADHD symptoms | Anomalies extend beyond fronto-striato-cerebellar circuits to (para)limbic regions | Some genes shared between ADHD alone and ADHD with emotion dysregulation | Treating “core” ADHD symptoms benefits emotion dysregulation, but separate treatment may also be needed |

Future Research Directions

Phenomenology and Pathophysiology

Treatment

Conclusions

Supplementary Material

- View/Download

- 104.57 KB

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).