Genes on chromosome 13q,

15 and possibly on chromosome 22,

4 influence the susceptibility toward a pleiotropic syndrome (the panic disorder syndrome) described by Weissman et al.,

15 which includes panic disorder, bladder problems, severe headaches, mitral valve prolapse, and thyroid conditions. A national survey compared 313 control subjects with 313 women with interstitial cystitis; the results showed that interstitial cystitis had significant associations with irritable bowel syndrome, CFS, fibromyalgia, migraine, depression, and allergies.

16 Despite the absence of bipolar spectrum disorders from the affective disorder spectrum, significant comorbidity between panic disorder and bipolarity was previously described.

17,18 Moreover, genetic links between bipolar disorder and panic disorder have been noted.

19,20 Notably, replicated studies have established linkage of bipolar disorder to chromosome 18q.

21,22 A higher occurrence of panic disorder in bipolar disorder linked with 18q suggests a genetic subtype of bipolar disorder identified by comorbid panic disorder.

23 Moreover, recurrent major depressive disorder and anxiety show links to 18q, supporting overlapping genetic etiologies.

24 In a recent meta-analysis, single nucleotide polymorphisms in chromosome 3p21.1 showed a significant association with mood disorders and possibly a shared genetic susceptibility locus for bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.

25 Thus, we contend that a spectrum disorder consisting of high rates of anxiety disorder would predict high levels of comorbidity with bipolar disorder.

Extending previous observations, we not only noted a relationship between ligamentous laxity and panic disorder, but we also saw comorbidity with other anxiety disorders, chronic pain disorders, immune disturbances, and mood disturbances. Clinical observation prompted the formulation of a domain-defined clinical syndrome, in which putative comorbidities exist along a spectrum and a patient may exhibit anywhere from one disorder under one domain to multiple disorders under multiple overlapping domains. In contrast with earlier spectrum disorder studies, we sought to integrate unipolar and bipolar mood disorders.

We identified five domains that captured the most commonly occurring comorbidities: anxiety, joint laxity, pain disorders, immune disorders, and mood disorders. This revised version of the previous spectrum disorder was therefore termed the ALPIM syndrome, forming an acronym representing the abovementioned domains. A cross-sectional naturalistic study was performed using a novel questionnaire with patients who were diagnosed with a core anxiety disorder and at least one index physical disorder. The first null hypothesis maintained that the comorbid conditions identified would not differ compared with rates from the general population. The first hypothesis stated that the rates of comorbid conditions that we observed in this cohort would exceed those observed in the general population, implying an enriched sample. The second null hypothesis stated that comorbidity within one ALPIM domain does not significantly increase the likelihood of a second comorbid condition, either within or between domains. We endeavored to provide statistical evidence for significant associations between conditions both within and between domains to refute the second null hypothesis.

The authors hypothesize that the ALPIM syndrome warrants preliminary consideration as a spectrum disorder, with predictable psychiatric and medical comorbidities, and this syndrome has potential relevance to our conceptualizations of boundaries within and between psychiatric and certain medical disorders.

Methods

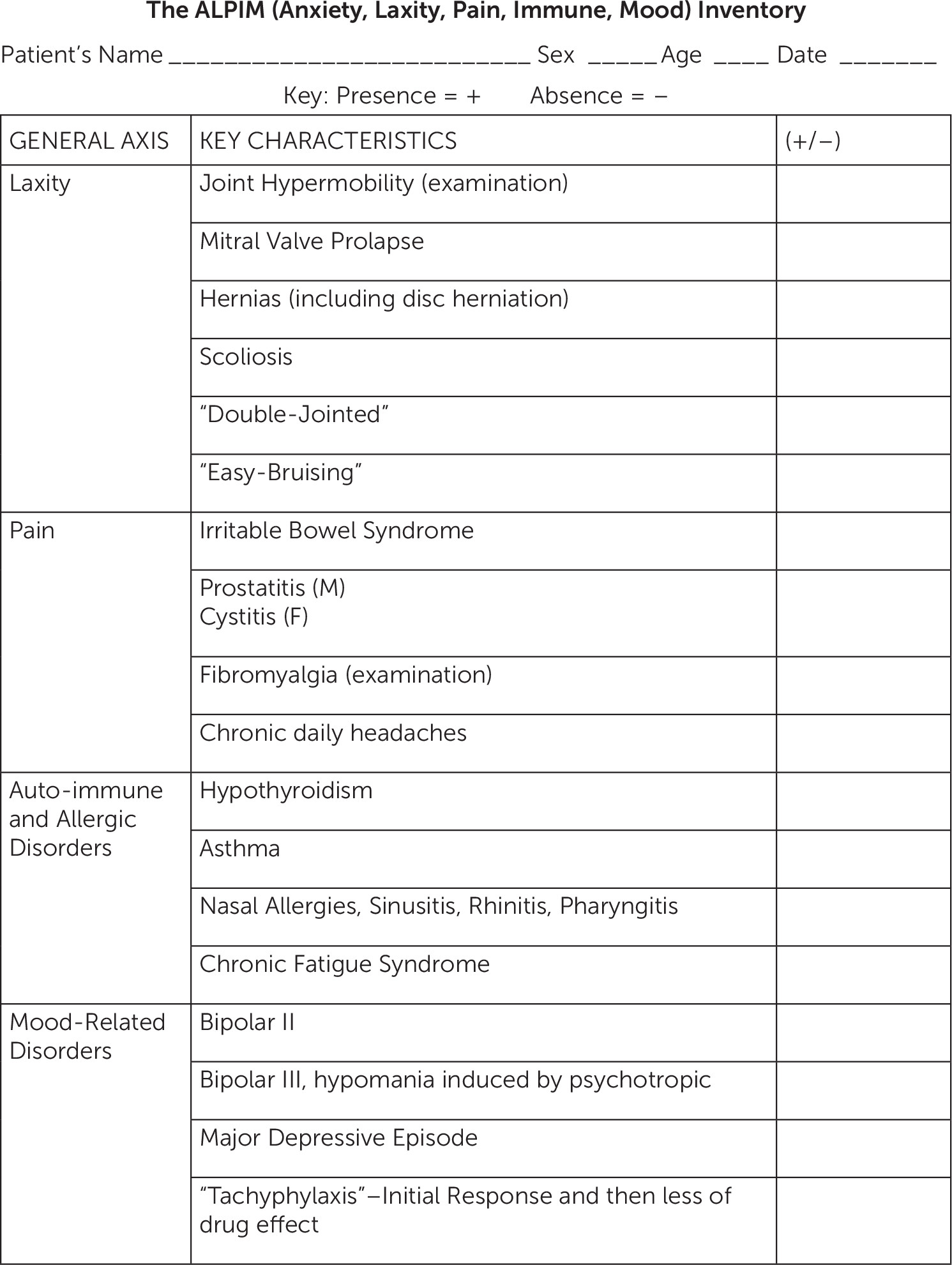

On the basis of clinical experience and the extant literature, a number of conditions were selected for each ALPIM domain to test for comorbidity in our cohort of patients. The anxiety domain includes panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and social anxiety disorder. The laxity domain includes joint laxity, mitral valve prolapse, scoliosis, double jointedness, and easy bruising. The pain domain includes fibromyalgia, chronic daily headaches, interstitial cystitis, and prostatitis. The immune domain includes asthma, hypothyroidism, CFS, and allergic rhinitis. Finally, the mood domain comprises bipolar I, bipolar II, bipolar III, major depressive episodes, and antidepressant medication tachyphylaxis. We developed the ALPIM Inventory Questionnaire (

Figure 1), and each subject was nonblindly evaluated with this instrument. This inventory was fashioned to detect the various conditions falling within the ALPIM spectrum. On the basis of clinical observation, disorders were not required to be contemporaneously comorbid; rather, lifetime occurrence was used. A combination of history taking, direct examination, and review of medical records was used to gather data. A total of 76 patients were recruited. In terms of ethnic background, all patients were white, except for one Latino patient. The mean age of the sample was 43.19 years (SD 11.03), with a minimum of 19 years and a maximum of 73 years. Of the 76 patients, 58 (76%) were women. Because of the location of the outpatient facility, patients were deemed to have middle to upper middle socioeconomic status. All participants had at least one

DSM-IV current anxiety disorder and one index disorder from the laxity, chronic pain, and/or immune domains (i.e., at least one somatic condition was present). The sample comprised outpatients followed either at the New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center or a private practice (J.C.). Only nine of 76 patients were recruited from the academic setting (11.8%). We do not have the denominator of patients from which the 76 patients with ALPIM syndrome were selected, but all patients were identified for this study within an 18-month period. Patients were recruited consecutively at each setting, provided that they presented with a comorbid physical condition in addition to a specified anxiety disorder. The low number of subjects recruited from the academic setting would appear to contradict the view that these were patients with a more complex set of problems. The breakdown of the sample predominantly implies a typical patient with anxiety that was treated in the community. Appropriate institutional review board approval was obtained.

Diagnostic criteria for clinical conditions included in the five ALPIM domains are as follows. For inclusion in the study, patients were required to have a primary

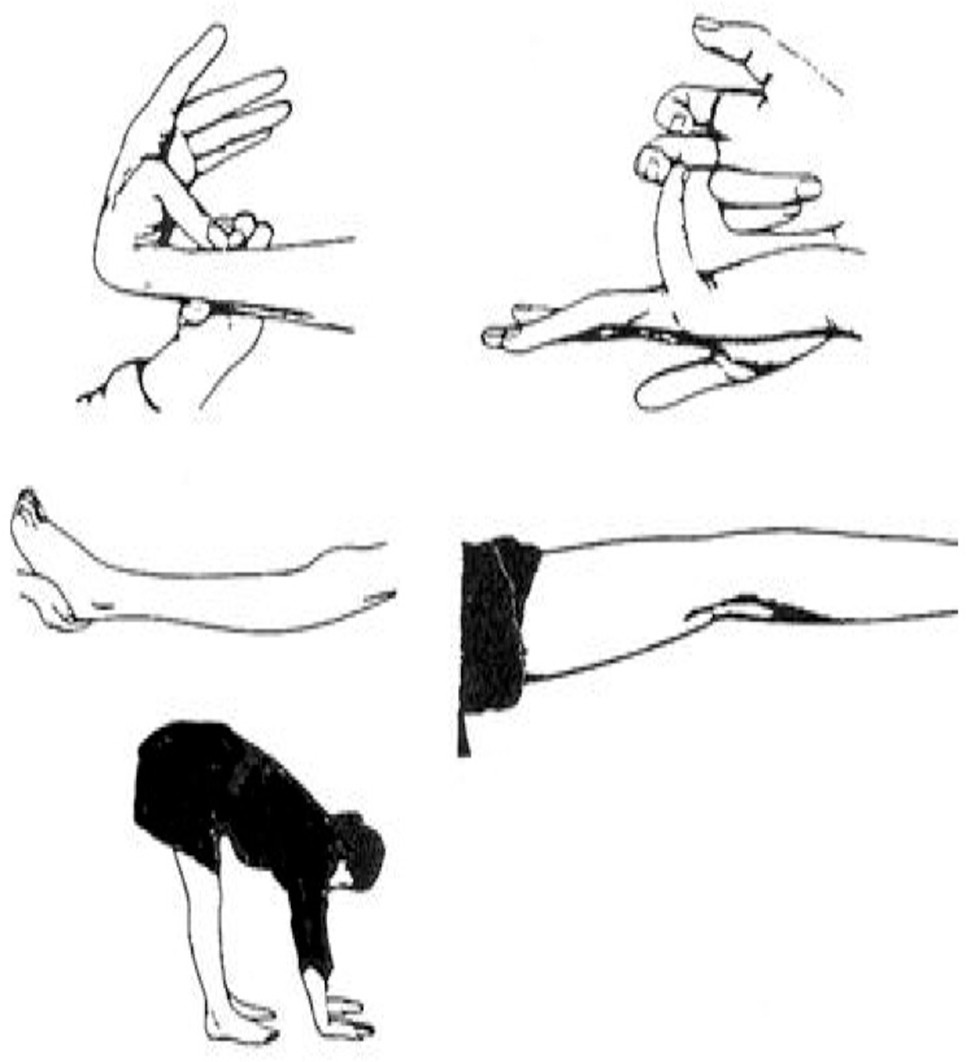

DSM-IV diagnosis of panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, or generalized anxiety disorder. Joint examinations were performed to detect joint laxity using Beighton’s criteria

14 (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Scores of ≥4 in men and ≥5 in women are considered positive for joint laxity. J.C. was first trained in this examination by Bulbena et al.,

27 and he subsequently achieved an interrater reliability of 0.96 with an independent blinded rater (Dr. Jane Fried).

Joint hypermobility syndrome includes mitral valve prolapse, scoliosis, double jointedness, and easy bruising.

14 Patients were required to have echocardiographic evidence of mitral valve prolapse and radiographic evidence of scoliosis. Double jointedness and easy bruising were subjective reports by patients. Double jointedness was recorded as positive when the patient responded yes to being asked “Have you ever considered yourself to be double jointed?” and could demonstrate exaggerated flexibility at one or more joint.

28 Easy bruising was recorded as positive if the patient gave a history of frequent bruising with minimal trauma. The diagnoses of mitral valve prolapse and scoliosis were not independently confirmed by radiologic evidence. The patient’s self-report of echocardiographic or radiologic evidence was considered sufficient.

Although hernias are included in joint hypermobility syndrome and were initially included in the ALPIM questionnaire, we do not include them in our tabulation of prevalence because many subjects endorsed hiatal and lumbar disc herniation, which made the diagnosis unclear. Therefore, hernia diagnosis was omitted from our analyses.

Our criteria for diagnosis of fibromyalgia were based on the 1990 American College of Rheumatology

29 classification criteria. However, subsequent studies

30,31 questioned the validity of these criteria. In addition, data from a study by Arnold et al.

32 imply that if one tender point is positive, the likelihood of other tender points being positive is very high. Because it was impractical to conduct an examination of 18 trigger points in an outpatient psychiatric setting, we conducted a mini tender point examination entailing six easily accessible tender points (

Figure 4). An affirmative diagnosis required four of the six tender points to be positive and endorsement of complaints of diffuse bodily pain, symptoms of fatigue, waking unrefreshed, and cognitive symptoms.

For interstitial cystitis and prostatitis, no specific diagnostic tests for either diagnosis are available and each is defined as chronic dysuria and pelvic pain with no known infectious etiology.

33,34 Patients were classified as having interstitial cystitis/abacterial prostatitis if they gave a history of chronic pelvic pain and dysuria that did not respond to antibiotics and associated with abnormal urinalysis and urine culture results. Interstitial cystitis and abacterial prostatitis were included as a single entity because of mounting evidence for significant overlap in epidemiology, pathophysiology, and even therapy.

35The Manning criteria were used for diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome.

36 The criteria include onset of abdominal pain linked to more frequent bowel movements, looser stools associated with onset of pain, noticeable abdominal bloating, sensation of incomplete evacuation >25% of the time, and diarrhea with mucus >25% of the time. The presence of more than three of the listed six criteria was considered diagnostic. Irritable bowel syndrome was only diagnosed if the patient reported a history of a negative colonoscopy.

Chronic daily headache

37 is a descriptive term that encompasses several different specific headache diagnoses characterized by frequent headaches, which are arbitrarily defined as headaches occurring >15 days per month or 180 days per year in the absence of an underlying structural or systemic disease.

37 We did not distinguish between chronic migraines and nonmigrainous headaches. Other disorders causing secondary headache were ruled out on the basis of the patient providing a history of a negative comprehensive physical, neurologic examination, and brain scan. Chronic daily headache was considered positive on our questionnaire only if the patient provided a history of being prescribed ongoing medication for headache relief.

37CFS was defined based on the revised Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria.

38 CFS comprises clinically evaluated, unexplained, persistent, or relapsing fatigue that is of new or definite onset, is not the result of ongoing exertion, is not alleviated by rest, and results in substantial reduction in previous levels of occupational, educational, social, or personal activities, along with four or more of the following: self-reported impairment in short-term memory or concentration, sore throat, tender cervical or axillary nodes, muscle pain, multijoint pain without redness or swelling, or unrefreshing sleep or postexertional malaise lasting ≥24 hours.

All patients who gave a history of either active or past asthma, including exercise-induced asthma, were included in the analysis. In addition, the patients had to provide a history of receiving current or past treatment with medications for asthma prescribed by their pulmonologists, internists, or primary care providers.

Primary hypothyroidism—commonly known as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis—was the first condition recognized as an autoimmune disease.

39 The patients included in our study were considered to have hypothyroidism once they provided a history of hypothyroidism diagnosed by blood testing. These participants may or may not have received a current thyroid replacement regimen. Of note, none of the patients had ever been treated with lithium.

Allergic rhinosinusitis

40 entails chronic anterior and/or posterior mucopurulent drainage, along with two or more of the following: nasal obstruction, facial pain, pressure and/or fullness, and decreased sense of smell.

The presence or history of a major depressive episode was established using

DSM-IV criteria. The major depressive episode could be current or past, and a distinction was not made regarding whether the episode was part of an underlying unipolar versus bipolar disorder. This was assessed using a semistructured interview based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R.

41Patients underwent a semistructured clinical interview and comprehensive psychiatric assessment to diagnose bipolar disorder. Patients were diagnosed with either bipolar I or II disorder based on the fulfillment of

DSM-IV criteria. Bipolar III disorder was diagnosed based on the presence of hypomania or mania resulting from the use of antidepressant medications.

42Tachyphylaxis, or tolerance to antidepressant drug therapy, generally refers to the loss of antidepressant efficacy during long-term use.

43–47 A significant decrease in clinical response was defined as a change in symptomatology that necessitated an adjustment in a stable pharmacotherapeutic regimen. Studies of tachyphylaxis showed that this phenomenon occurs in 25%−50% of patients during long-term antidepressant drug therapy.

44,46,47Patients with any unstable medical condition (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, cardiac disease, or seizure disorders) were excluded. One patient with stable myasthenia gravis was included. Treatment with statins for dyslipidemia was not an exclusion criterion.

Statistical Analysis

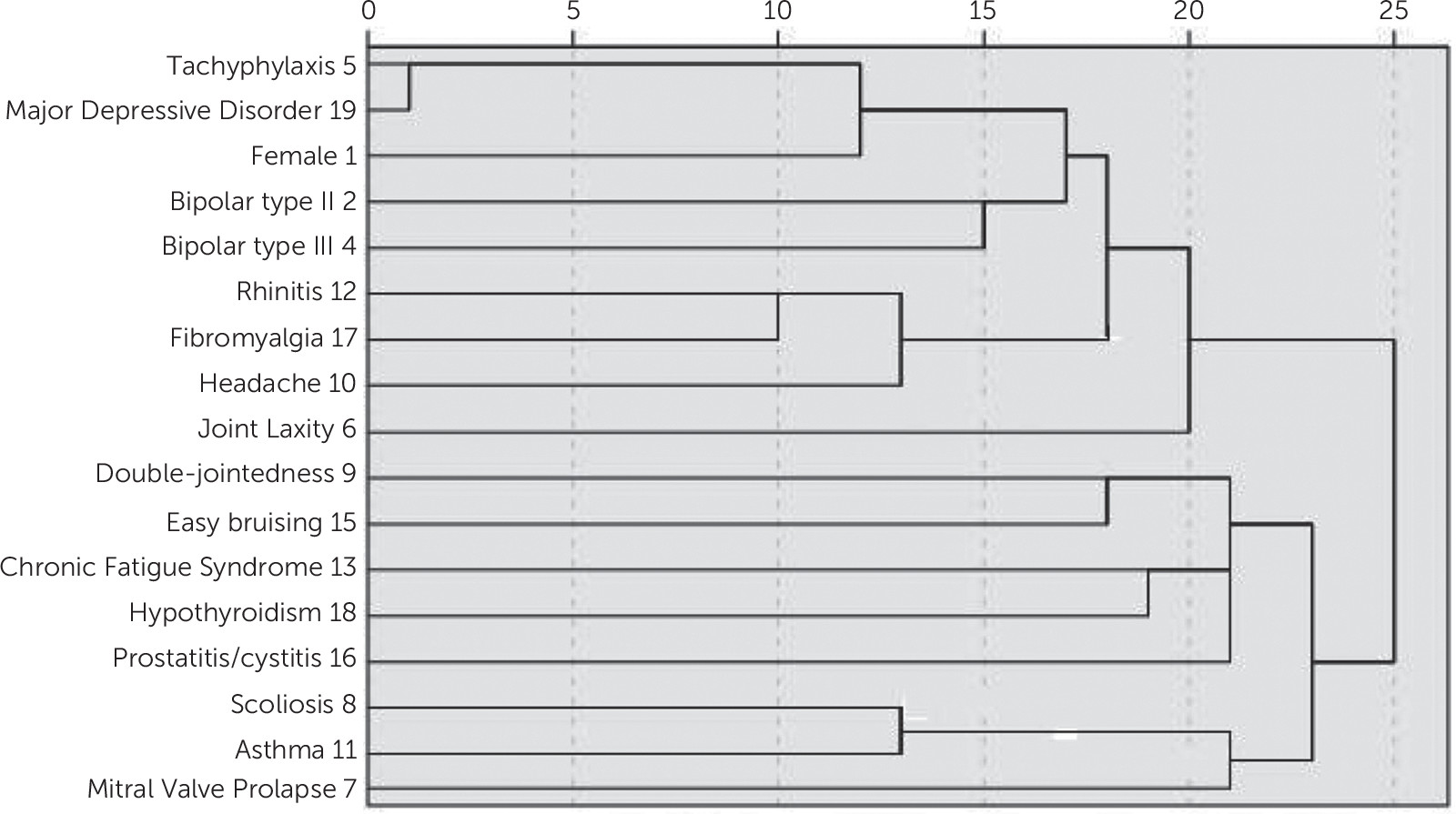

Data for 76 patients were available for analysis. On the basis of the analysis, we calculated and compared the frequencies, p values, odds ratios, and confidence intervals (CIs). SPSS (version 18; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to run logistic regressions to demonstrate associations within and between the ALPIM domains. The same data set was also used to run a cluster analysis to determine whether there were within- and between-domain groupings of the comorbidities under the ALPIM categories.

Discussion

We aimed to define a refined and extended spectrum disorder based on previous studies conducted by Hudson and Pope,

6 Bulbena et al.,

8 and Weissman et al.,

15 as well as the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases interstitial cystitis study

16 and a study on joint hypermobility syndrome.

62 This study, which was conducted with patients with at least one anxiety disorder and one physical disorder, tested our first null hypothesis that the comorbid conditions identified would not differ in rates from the general population. We refute the first null hypothesis because the rates of comorbid conditions we observed in this cohort consistently exceeded those observed in the general population (

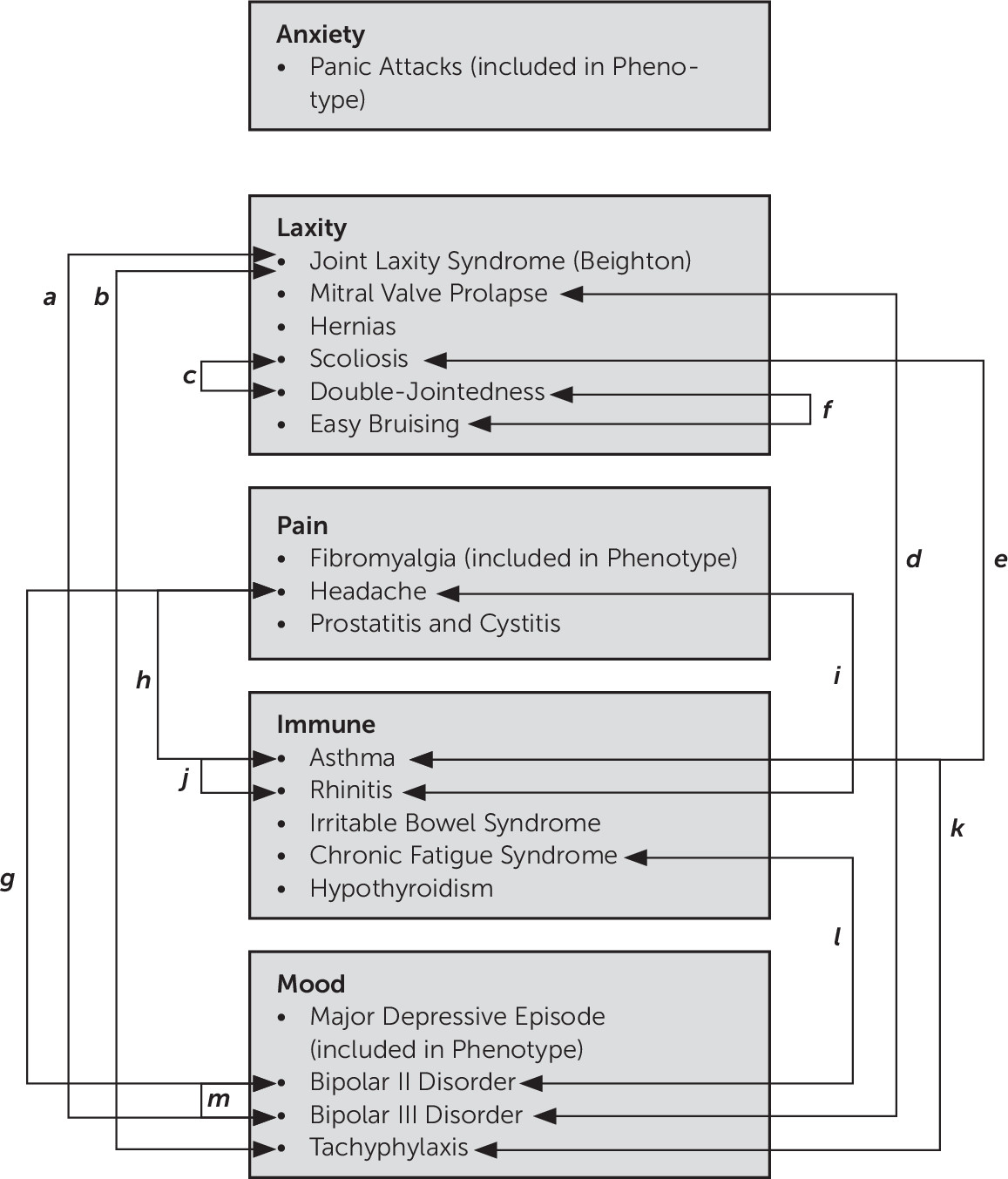

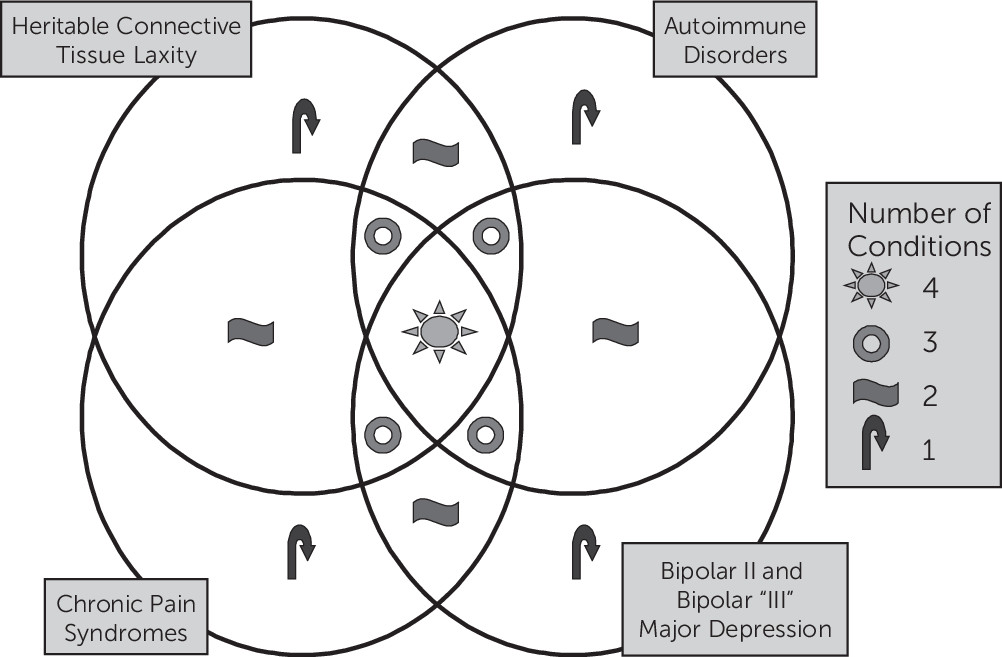

Table 1). The second null hypothesis stated that comorbidity within one ALPIM domain would not significantly increase the likelihood of a second comorbid condition, either within or between domains. We refute the second null hypothesis, noting that the logistic regression analyses revealed further evidence for significant comorbidity within and across domains and thus validates the underlying hypothesis of a spectrum disorder. We therefore argue that a statistically significant relationship exists between five potentially pathophysiologically linked domains: anxiety disorders, joint laxity, chronic pain disorders, immune dysfunction, and mood disorders (

Figure 7). The cluster analysis showed “soft clustering” of disorders within their putative domains. In addition, the Euclidean distances between clusters also suggested a close relationship across domains.

Our refined spectrum disorder systematically builds on the published descriptions of five prior spectrum disorders (

Table 3), such that our results are additive to the extant literature. In fact, the only novel condition we introduce to the prior literature, once integrated, is the high rate of bipolar disorder (and its attendant bipolar III and tachyphylaxis). Multiple overlaps between the individual spectrum disorders can be identified (

Table 3). Warren et al.

16 and the National Institute of Diabetes and Kidney Disease clinical trials group recently described a syndrome that includes interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel syndrome, CFS, fibromyalgia, migraine, depression, and allergies, which is perhaps most similar to ALPIM syndrome. However, our addition of bipolar II disorder, tachyphylaxis, and joint hypermobility to the syndrome identified by Warren et al.

16 is notable. On the basis of our literature review, the inclusion of bipolar II disorder seems justified by studies showing a higher incidence of anxiety among patients with bipolar disorder.

63We endeavor to demonstrate the difference between symptoms and disorders. Interestingly,

DSM-564 refers to the “somatic symptom disorder,” which involves anxiety and pain, in certain instances but is otherwise nonspecific. However, we now point out that disorders that were previously viewed purely as somatic symptoms by the psychiatric field have since been recognized as bona fide disorders in other fields of medicine. CFS, which has fought to constitute its own disorder, is one example. Our group previously reported that individuals with CFS have elevated levels of lactate in the CSF, and we used magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging to assess healthy volunteers and patients with generalized anxiety disorder

65 compared with healthy volunteers and patients with major depressive disorders.

66 These studies serve to delineate CFS as being biologically distinct from anxiety and mood disorders. Fibromyalgia, a disorder that was frequently viewed as comprising nonspecific somatic symptoms, is another example. Several serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are now approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of fibromyalgia. However, the efficacy of pregabalin,

67 an anticonvulsant that has no overt antidepressant properties but possesses anxiolytic effects, contradicts the view that antifibromyalgia effects are merely an alternate presentation of a mood disorder.

68 Compared with healthy volunteers, patients with irritable bowel syndrome have rectal distention that produces disproportionate pain and they have excessive activation of the anterior cingulate gyrus. Amitriptyline, an effective drug used to treat irritable bowel syndrome, attenuates pain from rectal distention, but only under stress conditions, suggesting a CNS site of action.

69 We therefore argue that a set of symptoms should not be relegated to somatic complaints reiterated by patients. Rather, patients are entitled to receive a medical diagnosis that has a biological basis and facilitates effective and, in certain instances, Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments.

This study has several important limitations that must be considered. Our study lacks a control group; therefore, the hypotheses must be regarded as preliminary. In future studies, it would be useful to examine psychiatric patients without the physical comorbidities of the ALPIM syndrome. The subjects did not necessarily suffer from the disease entities at the time of administration of the ALPIM questionnaire; rather, a lifetime history of the entities was considered. A Hawthorne effect, or an observer bias,

70 must be considered because the patient may have been motivated to nonselectively endorse the inquiries of the physician, leading to higher prevalence. Assessment of tender points is a standard component of the rheumatology examination. In this study, we performed an abbreviated form of the tender point examination. However, the diagnosis of fibromyalgia is moving toward nonreliance on tender point examination.

71 An additional concern is that patients who have many psychosomatic complaints tend to have more medical tests and thus are more likely to be able to report an abnormality. It appears plausible that patients with somatic cardiac symptoms are more likely to be diagnosed with mitral valve prolapse. However, the case for scoliosis appears less clear-cut. Scoliosis is usually revealed on routine examination or because of physical deformity, especially in a younger population.

Diagnoses were established using a semistructured psychiatric assessment in addition to the ALPIM questionnaire. The interrater reliability of the ALPIM questionnaire has not been established because this is a novel instrument examining these specific comorbidities and the rater was not blinded to the status of the subjects, leading to a potential bias of endorsement and false positive results. Perhaps the most convincing evidence for the diagnosis of the disorder, in addition to fulfilling diagnostic criteria, was that the patient had pursued medical treatment for that disorder (e.g., for irritable bowel syndrome, subjects were required to have abnormal colonoscopy results). Although this protected the likelihood of bias, we still acknowledge that future blinded studies are required. Of note, men were relatively underrepresented in the sample, which could be related to either sampling bias or a lower incidence of ALPIM in men. We acknowledge the vulnerability of this study to bias and we thus refer to this article as a preliminary report, encouraging the field to replicate our findings under more rigorous nonbiased conditions.

We conclude that patients with ALPIM syndrome possess a probable genetic propensity that underlies a biological diathesis for the development of the spectrum of disorders. Viewing patients as sharing a psychological propensity toward somatizing behavior essentially denies patients access to care for the diagnosable medical conditions with which they present. We emphasize that the proposal of ALPIM syndrome is not an entirely “newly recognized syndrome,” in that ALPIM syndrome contains significant elements of past syndromes. Our primary contribution is to add novel elements and groupings to previously described spectrum syndromes. We endeavored to capture these novel contributions (

Table 3) and document features either present or absent from previous syndromes. Our results provide further evidence to support a possible common pathophysiologic pathway toward the development of a related set of psychiatric and physical conditions, which were previously considered and, in certain instances, were unrelated.