Racial and ethnic health disparities in care are pervasive and have been well documented in several seminal government reports (

1–

3). In particular, racial and ethnic differences in need for care and treatment use have been documented. For example, a recent study found that with respect to alcoholism and drug abuse treatment, African Americans were more likely to report “no access” and Hispanic Americans were likely to report “less care than needed or delayed care” compared with non-Hispanic white Americans (

4). Once engaged in treatment, African Americans and Hispanic Americans were more likely to leave treatment early, and among those engaged in substance abuse treatment, they used fewer supplemental services than non-Hispanic whites (

4).

Few studies have examined racial and ethnic differences in substance abuse treatment-seeking populations; however, some differences have been found. One study found that African-American individuals with drug dependence who were in outpatient and inpatient drug treatment facilities had fewer comorbid psychiatric diagnoses than non-Hispanic whites (

5). Another study found that African Americans were more likely to be dependent on drugs only, whereas non-Hispanic whites were more likely to be dependent on alcohol only (

6). Similarly, other researchers found that African Americans were more likely than other groups to be given a drug-related substance use diagnosis other than an alcohol use disorder, even after the analysis adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and factors related to care setting and payment (

7). Another study found that African Americans were more likely than whites to be diagnosed as having cocaine dependence (

8). On the other hand, a study of individuals in public-sector treatment did not find any racial or ethnic differences in self-reported substance abuse (

9).

A limitation of previous research is that few investigations have examined the referral source, diagnostic, and length-of-stay profiles of persons from racial and ethnic minority groups admitted to substance abuse treatment. Documenting similarities and differences across racial and ethnic groups in diagnostic patterns and avenues of entry and departure from substance abuse treatment can assist not only in identifying disparities but also in illuminating the paths to treatment and treatment dropout that may uniquely affect African Americans and Hispanics. The purpose of this retrospective study was to examine patterns of referral source, diagnosis, and length of stay for African-American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white adults admitted to publicly funded and nonprofit inpatient substance abuse treatment facilities. Our hypothesis was that racial-ethnic group would be significantly related to referral source, diagnosis, and length of stay.

Methods

This analysis examined behavioral health data from patients in inpatient substance abuse treatment settings in the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (DMHAS). The DMHAS system of care comprises over 270 state and private nonprofit agencies that provide mental health and substance abuse services to individuals in the state of Connecticut. Records of inpatient substance abuse treatment are entered into a master DMHAS database. Data for this retrospective study were obtained through a computerized random extract of this central database for all unduplicated adults admitted to state inpatient substance abuse treatment facilities during 2004 and 2005. The variables considered in this analysis were required fields; therefore, few data were missing, and the quality of the data was high and consistent across sites. This study was approved by both the DMHAS Institutional Review Board and the Yale University Human Investigation Committee.

Originally, 500 African Americans, 500 Hispanics, and 500 non-Hispanic whites age 18 or older were selected for this study. Those whose length of stay was either 0 or >2.5 standard deviations above the mean were excluded, which left a sample of 1,484 adults (495 African Americans, 492 Hispanics, and 497 non-Hispanic whites).

Ethnicity and race served as the independent variable for all analyses and were categorized as African American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white. Individuals who self-identified as both African American and Hispanic were not included in this analysis because there were too few to create a separate group and to place them in either the African-American or Hispanic group would have made assumptions about their most salient ethnic identification. Native-American and Asian-American individuals were also not included in this analysis because of their limited numbers.

The dependent variables were referral source, primary axis I and axis II diagnoses at admission, and length of stay measured as the total number of days spent in inpatient substance abuse treatment services. In addition to symptom severity, which was assessed by the Global Assessment of Functioning score on admission, several demographic variables were assessed, including gender, age, marital status, education level, housing status, and employment status. Chi square tests for independence and analyses of variance were used to evaluate the distribution of the demographic variables across each racial-ethnic group. In addition, logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate whether treatment-related variables differed as a function of race-ethnicity after the analyses controlled for the demographic variables and for symptom severity.

Results

Some differences in demographic characteristics were found between racial-ethnic groups. The proportion of males was larger in the Hispanic group (82%, N=405) than among African Americans (68%, N=338), and non-Hispanic whites (69%, N=345) (χ2=30.65, df=2, p<.001). The proportion who had at least a high school education was lower among Hispanics (42%, N=205) than among African Americans (64%, N=310) and non-Hispanic whites (75%, N=362) (χ2=108.65, df=2, p<.001). African Americans were more likely to be older (mean±SD age=40.01±8.84) than Hispanics (36.08±8.91) and non-Hispanic whites (34.88±9.96) (F=41.63, df=2 and 1,481, p<.001). [A table summarizing data on demographic characteristics is available online in a data supplement to this report.]

Racial-ethnic differences in referral source, diagnosis, and length of stay may have been affected by the demographic differences. Thus we conducted logistic and linear regression analysis, controlling for demographic variables (gender, marital status, education level, employment status, and housing status) and symptom severity to determine the strength of the racial-ethnic disparities after controlling for possible confounds.

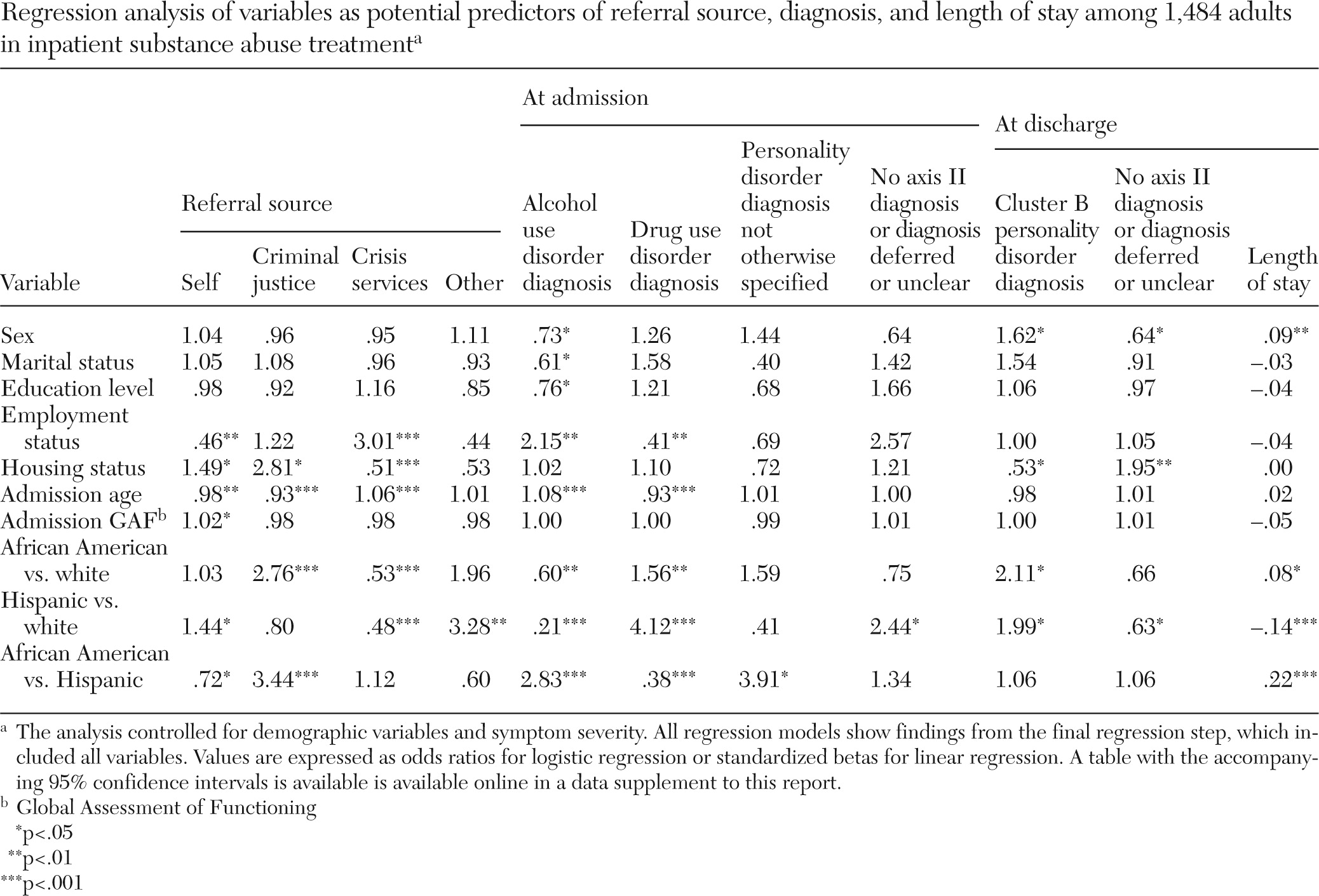

As shown in

Table 1, compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics were more likely to self-refer and to be referred by “other sources” and less likely to be referred by crisis-emergency services. African Americans were more likely than Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites to be referred by the criminal justice system. Non-Hispanic whites were more likely than the other two groups to be diagnosed as having an alcohol use disorder. African Americans and Hispanics were more likely than non-Hispanic whites to be diagnosed as having a drug use disorder at both admission and discharge (discharge results not shown). No differences between groups were found for other axis I disorders at admission or discharge.

However, African Americans were more likely than Hispanics to have a diagnosis of personality disorder not otherwise specified at admission. At admission, Hispanics were more likely than non-Hispanic whites to have no primary axis II diagnosis or to have it deferred or unclear. At discharge, however, African Americans and Hispanics were more likely than non-Hispanic whites to have a diagnosis of a cluster B personality disorder. At discharge Hispanics were less likely than whites to have a primary axis II diagnosis or to have it deferred or unclear. In addition, Hispanics had significantly shorter stays (13.79±15.73 days) and African Americans had significantly longer stays in treatment (21.38±19.43 days) than white non-Hispanics (19.02±19.52 days).

Discussion

Our finding that non-Hispanic whites were more likely than African Americans or Hispanics to be referred to inpatient substance abuse treatment by crisis-emergency services is contrary to findings of previous research (

4,

10). This finding may be related to another of our findings—that non-Hispanic whites were more likely to have alcohol-related diagnoses. Withdrawal from drugs other than alcohol, with the exception of barbiturates and benzodiazepines, does not constitute a medical emergency, and associated discomforts can be treated on an outpatient basis. Another explanation for our findings is that among poor, uninsured treatment-seeking populations, non-Hispanic whites may be less willing than others to seek public-sector, inpatient treatment for substance abuse problems.

Apart from differences in diagnoses of substance use disorders, we found no racial-ethnic differences in axis I disorders at admission and discharge. However, our analyses found differences in axis II diagnoses: African Americans were more likely than Hispanics to be diagnosed as having a personality disorder not otherwise specified at admission and more likely than non-Hispanic whites to have a diagnosis of a cluster B personality disorder at discharge. Hispanics were less likely than non-Hispanic whites to have an axis II diagnosis at admission but were more likely than non-Hispanic whites to have a cluster B personality disorder diagnosis at discharge. Follow-up analysis showed that the primary cluster B diagnosis of both African Americans and Hispanics was antisocial personality disorder.

A previous study had similar findings (

11). In that study, African Americans were more likely than persons from other racial-ethnic groups to receive a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder and Hispanics were more likely than other groups to receive no diagnosis of a personality disorder. However, other studies have found no differences by race or ethnicity in the diagnosis of personality disorders (

12,

13).

Our analyses demonstrated that Hispanics had significantly shorter inpatient stays than the other two groups and that African Americans had significantly longer stays. The findings for Hispanics are similar to those of a previous study of outpatient substance abuse treatment in which both African Americans and Hispanics were more likely to leave treatment prematurely (

14). The shorter stays for Hispanics in our study may be attributable to the limited availability of bilingual and bicultural staff in inpatient settings, which may result in shorter inpatient stays for Hispanics and referral to outpatient clinics where bilingual and bicultural staff are available.

Although the study included a fairly large sample (N=1,484) drawn from an array of inpatient substance abuse facilities, a limitation is that the findings are from a single behavioral health system over a limited time period. In addition, the study did not examine the variables in context for an individual person over time. Another study limitation is that we did not have information on the nationality or nativity of the Hispanic or African-American patients; there is wide variability in the cultural, national, racial, and ethnic background of individuals who are classified as Hispanic or African American, as well as heterogeneity in their patterns of health care utilization.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this investigation of racial and ethnic disparities in inpatient substance abuse settings examined an important and understudied clinical area. Identification of racial-ethnic differences can provide the foundation and impetus for interventions to increase the cultural competency of substance abuse treatment in order to achieve equity in substance abuse care and to appropriately address the treatment needs of all individuals seeking services. Our finding, for example, that Hispanics tended to leave treatment early and that African Americans spent more time in restrictive inpatient substance abuse settings, could be used as a basis for investigating the underlying reasons for these inequities, such as a lack of bilingual services and stereotypes about the dangerousness of individuals from particular groups, and for developing interventions that address cultural competence to address root causes.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding for this study was provided by the Office of Multicultural Affairs, Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services.

The authors report no competing interests.