The Affordable Care Act (ACA) (

1) is transforming health care delivery throughout the United States, increasing access for previously unserved populations and encouraging health care systems to provide coordinated, patient-centered care for chronic conditions to improve outcomes and reduce costs (

http://innovation.cms.gov). For California’s public mental health system, large-scale transformation began earlier, in 2004, when voters passed Proposition 63, the Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) (

2). The MHSA aims to address decades of shrinking mental health budgets, overreliance on emergency and hospital services, homelessness, and incarceration. Its 1% tax on personal incomes over $1 million has yielded average allocations of $1.3 billion annually, which represents 26% of funding for California’s public mental health system (fiscal year [FY] 2007–2008 to FY 2012–2013) (

3). Funds are restricted to developing and providing new services aligned with recovery principles: recovery from mental illness is possible; services are strengths based, not deficits focused; and services are provided with a patient-centered focus on clients’ treatment goals (

4).

Full-service partnerships (FSPs) are the core of MHSA’s recovery-oriented system transformation and receive the plurality of funds (

4–

6). FSPs use a modified version of assertive community treatment (

7). They provide intensive, integrated services for clients with severe mental illness who are unserved, underserved, or inappropriately served by existing services, with the aim of reducing hospitalizations, incarcerations, and homelessness (

4).

In Los Angeles (LA) County, which represents 25% of California’s population (

8), FSPs must have client-to-staff ratios ≤15:1, as well as treatment teams with a psychiatrist or other prescribing clinician, social workers or other mental health providers, housing and employment specialists, and client advocates; and services must be available 24/7 in the field (home or community) or clinic (

9,

10). Authorization for FSP enrollment occurs centrally, following community outreach to identify and recruit unserved clients with extensive prior-year homelessness (six months or more), incarceration (two or more episodes of at least 30 days total), inpatient psychiatric treatment (28 or more days of acute care or six months or more in an institution for mental disease [IMD] or a state hospital), or emergency psychiatric treatment (ten or more episodes), or dependent on family and at risk of these outcomes. Transfers from usual care are limited to 20% of FSP slots, with written justification of being underserved or inappropriately served by usual services (

11,

12).

MHSA seeks to make services more available (volume, location, and immediacy) but also recovery oriented and patient centered. The latter aims, representative of contemporary trends, cannot be evaluated without surveying stakeholders. Our 2006–2013 study of LA County’s MHSA implementation applied a prospective, mixed-methods design to three levels: system-level policies, clinic-level factors, and client outcomes. It evaluated implementation and process questions not addressed by previous evaluations of California’s MHSA or precursor programs (

13–

18), combining ethnography data, provider survey and interview data, and data from prospectively followed clients (FSP and usual care) with a quasi-experimental design, adjustment for regression to the mean, and administrative data (utilization), survey data (homelessness, incarceration, and symptoms/functioning), and interview data.

System intervention evaluations have found that system-level transformation may not affect client-level outcomes (

19–

24). One concluded, “Actions at the system level must express themselves through changes in treatment and subsequent clinician-client interactions” (

22). Evaluation of intermediate clinic-based factors, although crucial to determining what facilitates or impedes system-to-client impacts, often is lacking. Oversight of MHSA has been no exception. The Little Hoover Commission and the California state auditor both issued reports critiquing the extent to which state agencies and counties required, planned for, and complied with tracking of MHSA implementation goals and outcomes (

25,

26).

With this study, we filled a gap in this oversight, asking whether the LA County Department of Mental Health (LACDMH), with more than 250,000 clients annually (

27) and more than 4,000 adult FSP slots (

28), successfully transformed the structure of care, and, if so, how changes had an impact on client and provider experiences. Comparing FSP with usual care, we hypothesized that FSP clients would receive more outpatient and field-based services. Care would be more patient centered, with FSP clients and providers evaluating services as more recovery oriented and FSP clients reporting stronger client-provider working alliances. FSP providers would report greater engagement and higher morale, with stress levels lower (smaller caseloads) or higher (“do whatever it takes”). Subsequent studies will evaluate whether clinic-level changes improved client outcomes.

Methods

Sites and Sample

LACDMH operates 15 adult clinics and has contracts with operators of 51 additional clinics. We employed a quasi-experimental design in five clinics: four operated by LACDMH (two with FSP and usual care and two similar clinics that provided usual care only) and one contracted clinic (with FSP and usual care). We approached all treatment providers for three annual surveys (2007–2010). Forty-two FSP and 130 usual care providers completed one to three surveys (75%−77% response rate). We approached all FSP clients either at study onset or at the time of clinic admission. Of 222 eligible clients, 172 (77%) agreed to participate and 15 (7%) refused; repeated contact and scheduling efforts failed with 35 (16%).

To construct a usual care sample, we screened all preintake assessment forms by using approximate FSP criteria: a primary diagnosis of severe mental illness; Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score of ≤55 (

29); and prior-12-month history of hospitalization, emergency services, homelessness, incarceration, or family dependency. We approached clients close to admission, excluding those who had completed more than five visits. Of 617 eligible clients, 298 (48%) agreed to participate and 78 (13%) refused; repeated contact and scheduling efforts failed with 241 (39%).

The resulting sample consisted of 174 FSP clients and a nonequivalent comparison group of 298 usual care clients. Admission dates ranged from December 2006 to December 2009. Because recruitment was in person, clients who neither enrolled nor refused tended to be no-shows for clinic appointments; in usual care, many never engaged in treatment. After complete description of the study to potential participants, we obtained written informed consent for the survey and interview and HIPAA authorization for access to clinical data. Per human subjects protocol, clients under conservatorship or too ill to consent were ineligible.

Data Collection and Measures

Clients were followed for three years. Data included clinical and utilization data from LACDMH’s administrative database (2006–2013) (

30,

31), client and provider surveys and semistructured interviews, and more than 6,000 hours of clinic ethnography data (2007–2011). Institutional review boards at the University of California, Los Angeles, and RAND and LACDMH’s Human Subjects Research Committee approved the study.

LACDMH’s administrative database includes demographic, utilization, billing, and reimbursement data, including publicly funded state or fee-for-service hospitalizations and all mental health care provided or contracted by LACDMH: outpatient, day rehabilitation, emergency department, mobile response team, urgent care, acute inpatient hospitalization, IMDs, residential hospital alternatives (IMD step down and crisis residential), and jail mental health services.

Client surveys were administered at enrollment and every six months for up to three years, in English or Spanish, with in-person or phone follow-up surveys continuing after treatment discontinuation. This yielded 1,700 surveys (727 FSP and 973 usual care), with self-report, multiple-choice instruments and structured interviews assessing homelessness and incarceration. Provider multiple-choice surveys were administered yearly for up to three years, yielding 311 surveys (80 FSP and 231 usual care).

We interviewed 103 clients (41 FSP and 62 usual care) and 108 providers (21 FSP, 63 usual care, four clinic-wide, and 20 other programs), with yearly follow-up. Interviews (252 clients and 232 providers) were recorded, transcribed, and coded, yielding more than 14,000 discretely coded excerpts.

Mental health services utilization.

Utilization was aggregated by type: outpatient or day rehabilitation minutes, emergency or urgent care minutes, acute days (acute inpatient or crisis residential), and long-term days (IMD or IMD step down).

Homelessness and incarceration.

From clients’ retrospective reports of their day-by-day living situations and data on jail mental health services, we calculated days homeless and days incarcerated for six-month periods. We defined homelessness as street, vehicle, or temporary-shelter residence, excluding residence with family or friends or long-term programs (for example, transitional housing).

Organizational climate.

We evaluated providers’ work environments by using individual-level climate measures (engagement, functionality, and stress) and measures of work attitudes (morale) from the Organizational Social Context Measure (reliability alphas, .78–.94). Results are nationally normed T scores (mean±SD=50±10) (

32). Provider interviews included probes about MHSA-related clinic changes.

Recovery orientation.

We assessed client- and provider-perceived recovery orientation of services with the Recovery Self-Assessment Scale, Revised (RSA-R) overall and factor scores: life goals, involvement, diversity of treatment options, choice, individually tailored services, and whether services are inviting (

33). RSA-R scores derive from client or provider agreement with the presence of recovery-oriented program features on a scale from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. Provider interviews included probes about recovery and MHSA-related work practices.

Client-provider working alliance.

We assessed client-reported working alliance—“extent to which a client and therapist work collaboratively and purposefully and connect emotionally”—with the Working Alliance Inventory, Short (WAI-S) (subscales for goals, tasks, and bond; internal consistency alphas of .90–.92 for the subscales and .98 for the full scale) (

34). Scores evaluate client perceptions of the presence of a strong client-provider working alliance on a scale from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. Client and provider interviews included probes about client-provider relationships and treatment.

Analyses

Client analyses adjusted for clinic type, centered admission date (alone and FSP-interacted), and proxies for baseline illness severity, propensity or capacity for service use, and likelihood of arrest. These proxy variables include admission diagnosis, diagnosis of a substance use disorder, and GAF score; prior-year mental health service utilization (outpatient, emergency or urgent, acute inpatient, and long-term inpatient); prior-six-month homelessness and incarceration; and demographic factors (sex, age, race-ethnicity, and language). Survey analyses also adjusted for centered days between admission and survey (alone and FSP-interacted), and excluded surveys completed fewer than 60 days after clinic admission to ensure meaningful service evaluations.

Provider survey analyses adjusted for clinic type, training (M.D. or nurse practitioner, registered nurse or licensed vocational nurse, master’s or doctorate degree, or no advanced degree), and survey date.

All analyses were in Stata 14, with standard error adjustment for within-clinic clustering. Adjusted means for FSP and usual care are predictive margins with delta-method confidence intervals.

Outpatient utilization.

Time in program and program switching during the three-year follow-up were examined by using admission, discharge, and service use data. For service volume, outpatient mental health service use during the first year after clinic admission was regressed on FSP, with covariate adjustment as above, for the full sample and a complete-year subsample. Monthly adjusted utilization was calculated for the subsample to identify service intensity changes over time. Because of adjustment for prior-year values for each utilization category, FSP versus usual care differences are equivalent to difference-in-differences estimates.

Organizational climate, recovery orientation, and working alliance.

We hypothesized that evaluations of organizational climate, recovery orientation, and working alliance would be more positive in FSPs, with differences increasing over time as FSPs matured or, conversely, decreasing as transformations diffused to usual care. Because of clustering (surveys within individual and individuals within clinic), we examined overall FSP versus usual care differences by using random effects (Stata’s mixed), with random intercept for individual and standard error adjustment for within-clinic clustering. We examined within-program change over time by using the same model with FSP-year interactions (for providers, adding FSP-year interactions to existing year covariates; for clients, adding year and FSP-year interactions in lieu of admission date covariates) and calculating within-program year-over-year change by using Stata’s lincom and year-specific FSP versus usual care differences by using Stata’s margins.

Qualitative findings emerged from grounded-theory thematic analysis of ethnographic, interview, and focus group data (

35).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Provider characteristics.

Providers represented a range of training and clinic roles. The proportion of providers with no advanced degree was larger in the FSP sample than in the usual care sample (44% versus 21%, p=.003) (

Table 1).

Client characteristics.

The FSP and usual care client samples were similar demographically, except that the percentage of women was higher in the usual care sample (53% versus 41%, p=.02) as was the percentage of Hispanics (34% versus 25%, p=.04) (

Table 1). The prevalence rates of admission diagnoses and comorbid substance use disorders were similar; the proportion of clients with schizoaffective disorder was larger in the FSP sample (19% versus 10%, p=.01). Differences in functioning at admission were significant but small (GAF=40 for the FSP sample and 43 for the usual care sample, p<.001).

Preadmission homelessness, incarceration, and service utilization.

In the six months before clinic admission, a greater proportion of FSP clients than usual care clients were homeless (40% versus 30%, p=.02) and a greater proportion were incarcerated (24% versus 14%, p=.01) (

Table 2). Among those incarcerated, FSP clients spent more days incarcerated (73 versus 47, p=.03). Among those who were homeless, the duration of homelessness did not differ between the samples.

In the 12 months before clinic admission, a larger percentage of FSP than usual care clients received outpatient services (52% versus 26%, p<.001) and mobile response services (17% versus 10%, p=.02). Among clients who received outpatient services, FSP and usual care clients did not differ in the minutes of services received or the percentage of services that were field based. The percentage hospitalized did not differ between samples, but among those hospitalized, FSP clients had more hospital days (25 versus 12, p=.002). Only FSP clients received IMD step-down services (5%), crisis residential care (3%), and day rehabilitation services (1%).

FSP and Usual Care Outpatient Services

Of 174 FSP clients, 66 (38%) remained in their initial treatment episode for the three-year follow-up, and 81 (47%) received FSP-only services for less than three years, with an initial episode lasting a mean of 493±269 days. The other 27 FSP clients (16%) had an initial episode lasting a mean of 581±294 days, after which they were enrolled in non-FSP services.

Of 298 usual care clients, 89 (30%) remained in their initial treatment episode for the three-year follow-up, and 190 (64%) received non-FSP-only services for less than three years, with an initial episode lasting a mean of 374±234 days. The other 19 usual care clients (6%) had an initial episode lasting a mean of 325±228 days, after which they were enrolled in an FSP.

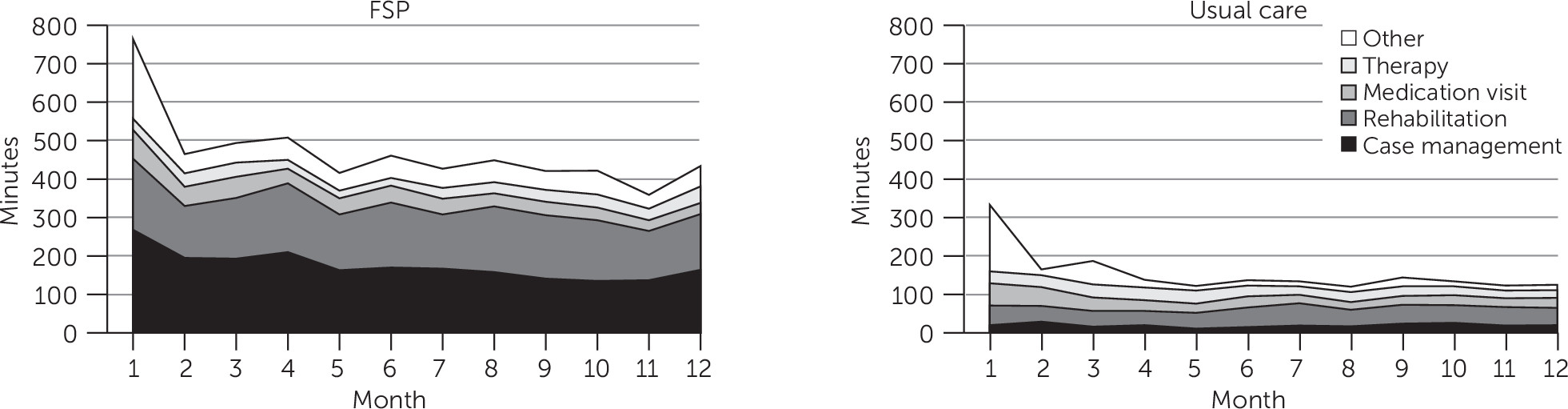

In the first year after clinic admission, FSP and usual care clients received dramatically different covariate-adjusted volumes of outpatient services (

Table 3). FSP clients averaged 5,238 minutes of such services, compared with 1,643 for usual care clients (p<.001); the differences were seen primarily in case management (1,930 versus 231 minutes, p<.001) and rehabilitation (1,695 versus 454 minutes, p=.001), and more visits were recorded as field based (22% versus 2%, p<.001). FSP clients received significantly more medication management, crisis intervention, and case consultation services; however, the differences in minutes of collateral services, no-contact services, diagnostic services, therapy, or day rehabilitation were not significant.

Sensitivity analysis restricted to clients with an initial episode of at least one year (FSP, N=137, 79%; usual care, N=185, 62%) yielded similar results (not shown).

Figure 1 shows adjusted monthly utilization for this complete-year subsample. For both samples, intensive initial services tapered off to maintenance levels. FSP services were more intensive than usual care throughout (month 1, 766 versus 332 minutes, p=.02; average for months 2–12, 442 versus 139 minutes, p<.001).

Organizational Climate

FSP and usual care providers reported similar organizational engagement and functionality (

Table 4). FSP providers reported significantly higher stress (score of 55.0 versus 51.3, p<.001) and lower morale (48.1 versus 49.6, p<.001), despite having small caseloads. These differences emerged in FY 2008–2009 and persisted into FY 2009–2010. One provider said, “You can never do enough for these clients. The FSP slogan, ‘Whatever it takes. . .’—that is so innovative and you can really make a difference. . . . But eventually that slogan wears on you. That’s an incredible amount of responsibility to put on us. . . . A caseload of 15 sounds so small, coming from outpatient clinics of 200, but look at what we’re trying to do. . . . In outpatient . . . I would only know half of them. I would have a few that met with me for therapy. Other than that, I would see my clients once a month. If they didn’t show up, I’d give them a call once. If they didn’t answer, oh well. . . . [With FSP] I might have to show up at their door. . . . We’re constantly checking to see if they’ve been hospitalized; checking to see if they’ve been put into jail.”

Interviews and ethnographic observations suggested that differences between FSP and usual care went beyond service volume. Providers worked as teams and took seriously the obligation to “do whatever it takes” for their small caseloads.

Program Recovery Orientation and Working Alliance

Providers and clients, on average, rated both programs as having recovery-oriented features (RSA-R) (

Table 4). Providers rated FSP programs significantly higher than usual care programs on two of six subscales and overall (3.7 versus 3.6, p=.001), although year-specific estimates (not shown) differed significantly only in FY 2008–2009 (overall and on four subscales). On the RSA-R, clients rated FSP programs higher on five of six subscales and overall (3.8 versus 3.5, p<.001); all differences were present for the FY 2008–2009 and FY 2009–2010 year-specific estimates, and some were present for the FY 2007–2008 and FY2010–2011 estimates (not shown).

Although clients in both programs reported a positive working alliance with providers (WAI-S), FSP ratings were higher on all subscales and overall (3.8 versus 3.6, p<.01); all differences were present for FY 2007–2008, and some were present for FY2008–2009 and FY2009–2010 (not shown).

Client ratings were consistent with data from the semistructured interviews. Usual care clients were less likely to describe feeling close to providers and more likely to express difficulty getting needs met. As one usual care client said, “Not being able to get in touch with your caseworker or psychiatrist when you need them, that’s very difficult. I get to see Dr. [name] when my appointment is, and that’s it.”

A common complaint was that clinicians were overburdened. One usual care client said, “I’m not saying he’s a bad psychiatrist. It’s just that certain things that he should be asking, and since he don’t ask, I don’t feel comfortable volunteering anything. . . . Maybe this place isn’t for that. . . . He should have less caseload. . . . At least try to talk to a person in there for 45 minutes . . . to see what’s going on, and they don’t do it here.”

In contrast, FSP clients reported close, available relationships. One said, “It’s a great relationship. They support me a lot. They’re almost like family to me because of what they try to do.” Another described feeling respected and listened to, in person and through care coordination meetings: “They don’t treat me as someone who’s crazy. They listen to you. They have meetings every morning; they share that kind of stuff. . . . I’ve never felt disrespect. I’ve never felt judged. I’ve always felt, you know, that their goal is really to help us to help ourselves.”

The programs’ structures—FSPs’ small caseloads, daily team meetings, and mandate and resources to “do whatever it takes” versus usual care’s large caseloads and restriction of contact to brief scheduled appointments—shaped not just service volume, but clients’ treatment relationships and experiences.

Discussion

Following a policy mandate, LA County’s public mental health system transformed the structure of care through its new FSPs. Smaller caseloads, greater resources, team-based care, and higher expectations of providers translated into more case management, rehabilitation, and field-based services.

These structural and service-volume differences affected clinicians’ and patients’ experiences of care. Clients and providers rated both programs as recovery oriented, with higher ratings for FSP, and interviews revealed substantial differences in services and client-provider relationships. Although FSPs’ recovery focus likely played a role, our data suggest that FSP clients reported stronger client-provider working relationships and a more patient-centered experience because providers had the resources and mandate to “do whatever it takes,” with small caseloads allowing them to be available to clients, discuss broader issues, plan for clients’ futures, and devote resources to clients between visits via team meetings and follow-up of missing clients. This contributed to FSP clients feeling that they had someone to work with and talk to, whereas usual care clients sometimes felt that treatment scratched the surface and was bounded within scheduled visits.

Although the restructured services were beneficial to clients, providing these services imposed burdens on the system: more resources were required for higher service intensity, and providers experienced stress because they were responsible for providing coordinated, accountable, patient-centered care. These findings anticipate potential issues with ACA’s encouraged shift toward patient-centered, accountable care for patients with complex, chronic needs.

Some limitations should be noted. Although we selected our usual care client sample on the basis of eligibility criteria approximating those of FSP, usual care providers treat the full range of clients meeting DMH medical necessity criteria, all of whom have a Medi-Cal reimbursable mental health diagnosis and impairment in an important area of life functioning but many of whom do not meet FSP eligibility criteria used to identify the most severely ill. Provider responses may reflect case mix in addition to program structure and treatment approaches. However, ethnographic observations and interviews supported the interpretation that doing “whatever it takes” increased FSP providers’ work-related stress.

Conclusions

Our evaluation of MHSA’s impact on clinic-level factors fills a gap in oversight of this large system intervention by showing, at a micro level, how MHSA funds were used to expand and transform services in a core MHSA program in California’s most populous county. These findings are important to evaluating and improving MHSA’s implementation and will inform an upcoming analysis of FSP client-level outcomes over a three-year follow-up: emergency and inpatient utilization and costs; homelessness, incarceration, and employment; and symptoms and functioning.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the many individuals who contributed to the evaluation of the Mental Health Services Act: Los Angeles Department of Mental Health administrators and clinicians; researchers Thomas Belin, Ph.D., Susan Ettner, Ph.D., Alison Hamilton, Ph.D., Gerald Kominski, Ph.D., Susan Stockdale, Ph.D., Kenneth Wells, M.D., M.P.H., and Alexander Young, M.D., M.H.S.H.; project managers Briana Hedman, M.A., Richell Jose, B.A., Amanda Nelligan, M.A., and Rebecca Wilkinson, M.S.P.H.; and the ethnographers, peer specialists, and survey specialists who enrolled, surveyed, and interviewed clients during the nearly four years in the field, including Jorge Avila, B.A., Rebecca Carrillo, Ph.D., Mayte Diaz-Dryer, M.P.A., Deborah Hastings, Melissa Park, Ph.D., and Deborah Peralta.