Major depression is a highly prevalent chronic condition, with high societal cost, and was the leading cause of disability in 2017 (

1). Depression is associated with low educational and economic attainment; it also is associated with marital disruption and suicide, each of which incurs costs from lost productivity and health and mental health treatment (

2–

4). Residual depressive symptoms, which occur when patients partially recover from a major depressive episode, represent a pervasive ongoing burden that is often left untreated and increases the risk of major depressive relapse (

5,

6).

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is an empirically supported program that teaches emotion regulation skills for reducing residual depressive symptoms and confers a 43% reduction in relapse risk (

7–

10). Like many psychotherapies, MBCT faces dissemination challenges, including shortages of MBCT-trained therapists, service cost, and logistical hurdles (

11). These access barriers provided the rationale for a Web-based program informed by MBCT, called Mindful Mood Balance (MMB). MMB was evaluated in a large randomized controlled trial (N=460) and found effective for reducing residual depressive symptoms over a 12-month follow-up period (

12). These data suggest that MMB may be a scalable solution for expanding availability of MBCT.

Results of the few cost-effectiveness analyses of Web-based depression treatments have been mixed. Some have shown cost-effectiveness within $20,000 or $50,000 per year willingness-to-pay thresholds (which are likely too high for U.S. health plans to consider), but none have shown significant reductions in costs from averted health care utilization (

13–

16). Internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy programs average 50% probability for cost-effectiveness at a $0 willingness-to-pay threshold (

17). Web-based programs may promote help-seeking behavior, leading to increased outpatient service utilization. Traditionally, this may be interpreted as a detrimental impact of Web-based programs from a cost-effectiveness standpoint, but the context of resource and access limitations within the U.S. mental health care system must also be considered.

Results

Among the 460 patients recruited for the trial, 389 (85%) had completed a PHQ-9 during the follow-up period and were included in the main analysis (UDC, N=210; MMB+UDC, N=179).

Table 1 presents baseline demographic characteristics; no significant differences were noted on any self-reported demographic, risk factor, or treatment history variables. Patients in the MMB+UDC group had an average of 28.72 more DFDs in the 12-month follow-up period, compared with UDC (interquartile range=40.91).

During the 12-month follow-up period, patients in the MMB+UDC group had slightly higher outpatient mental health costs, mostly driven by more psychotherapy visits (cost difference of $27.05 for psychotherapy visits) (

Table 2). Costs for second-generation antipsychotics were substantially higher for the MMB+UDC group, which was found to be driven by 18 more prescriptions dispensed of aripiprazole among fewer than five patients. Abilify was a high-cost medication during the study and accounted for over 90% of the costs in that category for both groups. Overall, the incremental cost, or the difference between MMB and MMB+UDC with all costs incorporated, was $431.54.

Incremental cost per DFD gained ranged from $9.63 to $15.04 for different cost inputs (

Table 3). When only MMB licensing and labor costs for recruitment and coaching were included, the incremental cost was $9.63 for each additional DFD. Negligible increases to $10.72 and $11.00 occurred when psychiatric and psychotherapy visits and antidepressants were added, which represent the highest overall service costs for this sample. A larger increase in cost per DFD ($15.04) was observed when all psychotropic costs were added, which was driven by more prescriptions dispensed of aripiprazole in the MMB+UDC group.

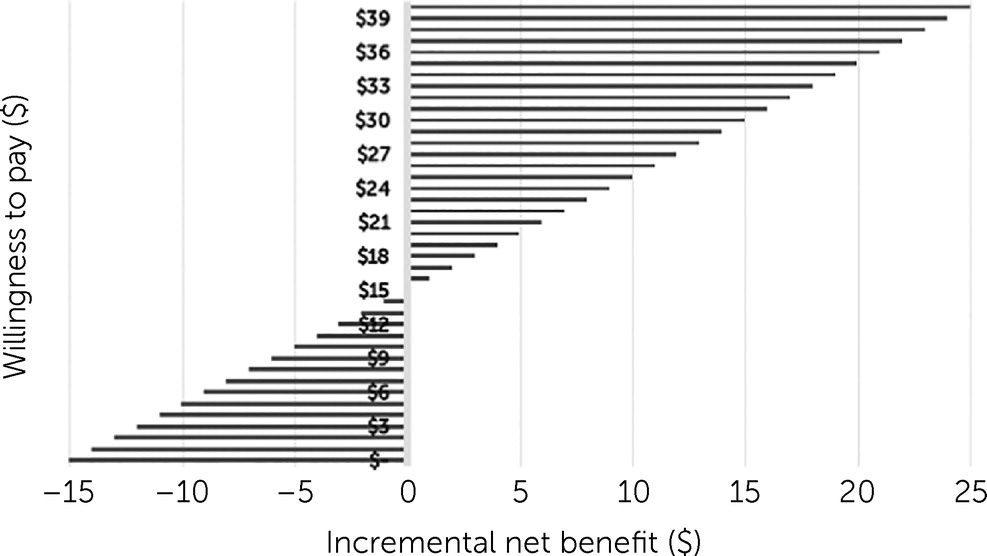

Figure 1 shows that at $15.04 willingness to pay for an additional DFD, MMB was cost neutral.

In the sensitivity analysis, patients who were excluded because they did not have follow-up PHQ-9 scores had negligible differences for medication and psychiatric and psychotherapy services (

Table 4). Overall, this shows that those who were lost to follow-up did not seek more outpatient mental health care, but their clinical outcomes remain unknown. In the exploratory analyses, higher use of emergency and inpatient services was noted for the UDC group (17 inpatient stays for the UDC group versus 10 for the MMB+UDC group).

Table 4 shows a cost savings of –$0.04 per DFD when patients lost to follow-up were eliminated from the analysis; however, the cost difference disappeared when all patients were included ($13.84 per DFD).

Discussion

Health insurance companies are now offering several mental health digital programs to their members as a benefit (

31); however, few have undergone rigorous evaluation to understand costs (

32). This cost-effectiveness study compared the MMB program to UDC by examining differences in program costs, costs for psychiatric and psychotherapy visits, and psychotropic medication costs within a large integrated health system. MMB had a cost per DFD of $9.63 for program costs only and $15.04 when all medication and services costs were included. Most of the increase over program costs only was attributed to high-cost medication choice and very little to differences in outpatient psychotherapy or psychiatric visits. Results show that MMB offers an effective and low-cost adjunctive service to traditional mental health services for treatment of residual depressive symptoms, which health systems should consider adopting.

No significant cost offsets were noted for outpatient mental health care or antidepressant medication use during the follow-up period. However, this is not surprising given the findings of prior studies of MBCT and antidepressant medications (

33). Although the meditation and mindfulness skills learned in MMB may help avert use of mental health services, MMB also teaches patients to recognize warning signs to know when to engage in services, which may increase treatment seeking.

The incremental costs per patient for MMB were $431.54 for a gain of 29 DFDs. This is respectable, compared with costs of other prominent programs for depression offered through integrated health systems. For example, cost-effectiveness studies of collaborative care management for depression, which typically involves both in-person and telephone support, have indicated incremental costs of $454–$960 per patient over usual care, with 18–58 incremental DFDs gained over 1 year (

32,

34–

37). The incremental costs of $431.54 are comparable to those of other effective Web-based depression programs, which reported incremental costs of $52 (

16), with little coaching or therapist cost but with limited engagement and costs of $703 (

14) for synchronous therapist contact and high engagement. This would indicate that MMB may be equivalent to collaborative care in overall cost-effectiveness and within typical cost ranges for other Web-based depression programs with some coaching support.

The literature is sparse on robust cost estimates for in-person MBCT, compared with usual care, but two studies offered estimates of the labor cost for in-person MBCT programs. Cost per patient for an altered version called “MBCT with support to taper or discontinue antidepressant treatment” was reported to be approximately £112 ($168 in 2015 dollars) (

33). An earlier study of traditional MBCT estimated that the labor costs per patient of the in-person program were the equivalent of 3 contact hours with a therapist, which would be approximately $300 based on the Medicare fee schedule (

7). The equivalent to these estimates from the study reported here is coaching costs, which were $96.67 per patient over the course of MMB. Of note, in a meta-analysis, the hazard ratios (HRs) for depressive relapse were nearly the same for in-person MBCT (

10) and for Web-based MMB (

12) (in person MBCT, HR=0.69, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.58–0.82; Web-based MMB, HR=0.61, 95% CI=0.39–0.95). This indicates that Web-based MMB with e-mail or phone coaching offers a substantially lower-cost alternative, compared with in-person MBCT, with nearly equivalent outcomes.

It is important to consider that patients who decide to enroll in a study for MMB may have different preferences from those choosing in-person MBCT or another in-person program, such as collaborative care for depression. Web-based MMB offers an alternative for patients with logistical barriers or social anxiety or simply for those who do not prefer in-person group-based programs (

38). However, some patients may learn best in an in-person group environment, and those without stable Internet access would not be able to participate in a Web-based program. These barriers may explain why 37% of patients did not complete at least four sessions of MMB (considered an adequate dose). However, this attrition rate is lower than rates of >50% reported for prior Web-based depression programs (

39). Regardless, future studies of MMB and other Web-based depression treatments should examine mediators of successful treatment response and attrition to improve delivery of these programs, especially because treatment failures and delay exacerbate the severity and chronicity of illness course (

40). To address the burden of depression, it is important that multiple modalities of treatment be offered that address differences in patients’ preferences and access. This analysis indicated that MMB offers a highly feasible and scalable model for health systems looking to expand their offering of evidence-based programs for depression.

This study had several advantages and some limitations, compared with prior cost-effectiveness studies of Web-based depression programs. Many studies have not captured program costs (e.g., staff time to engage and retain patients) or have used patient self-report measures for service utilization, whereas this study captured costs associated with implementing the program and estimated actual service costs collected from EHRs and claims within a capitated health plan. One limitation is the potential for missing mental health service costs paid for privately outside the health system; however, these should be minimal because private mental health care would have higher out-of-pocket costs, compared with the covered benefits reported here. White females accounted for about three-quarters of the sample, which may affect generalizability with respect to race, ethnicity, and gender. Data for patient time costs, presenteeism, and absenteeism were not available, and thus an analysis from a societal perspective was not possible.

Another limitation was that the sample size was too small and the costs variability too high to be interpretable for emergency department and inpatient costs associated with mental health and substance abuse issues and suicide ideation and behavior. This information was included for transparency, but it is not likely accurate to say that MMB is cost-saving, considering that the inclusion of a handful of patients who were lost to follow-up changed the cost per DFD from –$0.04 to $13.84. The latter is close to the cost when only outpatient and medication costs were included ($12.71). This is also illustrated in the large cost differences associated with aripiprazole for a small additional number of administrations in the MMB group. Aripiprazole is prescribed to patients as adjunctive to antidepressants when antidepressants alone lack adequate effectiveness (

41). This study was powered on the effectiveness outcomes and not on cost outcomes. Therefore, this study was not equipped to absorb these differences associated with high cost variance from emergency services, inpatient services, and high-cost medications. The total outpatient and emergency department visits, inpatient stays, and medication administrations are included in

Table 2 to show proportionally that most of the utilization was associated with antidepressants and outpatient visits. When only antidepressants medications were incorporated, the incremental cost per DFD was $11.00. However, the more conservative estimate that incorporated aripiprazole is reported because it is possible that MMB caused more treatment-seeking behavior, which resulted in the additional medication administrations. This study did not report quality-adjusted life years, because this metric is rarely used by policy makers (e.g., CMS and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force) or by health system decision makers in the United States, and there is controversy about the use of this metric because of potential violation of the Americans With Disability Act (

42).