Over the past two decades, the incarceration rate for women has steadily increased (

1,

2,

3). Relative to their male counterparts, women incarcerated in state prisons are more likely to have psychiatric disorders and a history of physical and sexual abuse (

4,

5,

6). Roughly half the women in state prisons were under the influence of alcohol or drugs when they committed their offense (

2). Evidence, although limited, suggests that most of these women receive very little, if any, medical or mental health treatment in the community (

7).

Barriers that reduce access to treatment in the community are well known and include lack of health insurance, organizational complexities, and society's attitudes (

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13). Ability to gain access to treatment is likely to be improved in prison, in part because individuals in prison have a constitutional right to medical and mental health treatment and in part because financial, organizational, and transportation barriers in the community are considerably less significant. However, the availability of behavioral treatment in prison is also known to vary. Data on mental health spending by 16 state prison systems indicated that these states spent, on average, 17 percent of their correctional health care budget on mental health services, with a range from 5 percent (Minnesota) to 43 percent (Michigan) (

14,

15). Mental health spending represented roughly 18 percent of the correctional health care budget for New Jersey prisons in 2002. Treatment for substance abuse problems in prisons is generally less available than treatment for mental health problems, because courts have not extended the constitutional right to health care during incarceration to include treatment for substance abuse problems (

16).

It is well established that people with mental illness, as well as those with co-occurring substance use disorders, have diseases that are amenable to treatment. Persons with persistent and severe behavioral health problems are especially responsive to treatment (

13). Engaging individuals with behavioral health problems in treatment and maintaining such involvement is associated with better symptom control, as well as improved mental health, functioning, and quality of life (

17). Yet what remains unclear is the role that prison plays in this process.

The central issues addressed in this study were whether women with behavioral health needs are more likely to receive treatment for these problems in prison or in the community and to what extent prison disrupts or establishes involvement in treatment. These issues were addressed by comparing the behavioral health treatment needs of female inmates in New Jersey with their use of these services before and during incarceration.

Methods

Data and procedure

Data were collected as part of a population survey of female inmates (N=1,165) in the only state correctional facility in New Jersey for women. Participant recruitment and protections were approved by Rutgers University's institutional review board. The survey, available in English and Spanish, was administered in August 2004. All inmates onsite were invited to participate in the survey, including those in medical and administrative segregation. A small number of women (fewer than 25) were not given the opportunity to complete the survey because they were off campus or otherwise unavailable. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Surveys were completed onsite over a three-day period and within 20 minutes of their distribution. Researchers were available for assistance. Overall, 908 surveys were completed, representing a response rate of 78 percent. No information was collected on the characteristics of nonrespondents.

Variables and measures

Need and use of behavioral health treatment before and during imprisonment was gathered through a series of eight questions to which the response options were either yes or no. The first four questions asked respondents whether they had needed or received treatment for substance abuse or mental health problems in the two years before their incarceration. The same set of questions was repeated with reference to the period that the inmate spent in prison.

Other variables measured were age, race or ethnicity, marital status, number of children younger than 18 years, highest level of education (less than high school, high school, or more than high school), and whether the respondent was a victim of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse before incarceration. Notably, this measurement of trauma lacks the specificity needed to understand the relationship between trauma and treatment inside and outside of prison and represents an important weakness of the current study. Finally, because receiving treatment is largely an outcome of having some form of ability to pay, participants who reported being covered by Medicaid or receiving Supplemental Security Income or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families benefits before incarceration were coded as having health insurance.

Results

Respondents' characteristics

Female inmates who participated in this study (N=908) were mostly African American (477 women, or 54 percent), between 21 and 30 years of age (642 women, or 73 percent), and had a high school education or less (512 women, or 57 percent). Almost three-quarters (613 women, or 70 percent) were single, and 366 (43 percent) reported having no children younger than 18 years. About half of all respondents (451 women, or 49 percent) were first-time inmates who were serving a sentence of less than five years for a drug-related conviction. In addition, 360 women (42 percent) reported being a victim of sexual assault, 469 (54 percent) reported being a victim of physical abuse, and 540 (62 percent) had been emotionally or verbally abused.

Match between needs and treatment before incarceration

A total of 504 respondents (56 percent) reported needing behavioral health treatment before incarceration. Among these respondents, 93 (18 percent) said they needed treatment for mental health problems, 242 (48 percent) said they needed treatment for substance abuse, and the remaining 169 (34 percent) said they needed treatment for both mental health problems and substance abuse. A majority of these women (311 women, or 62 percent) reported receiving behavioral health treatment some time during the two years before incarceration. Among those who reportedly received treatment, 108 (35 percent) were treated for a mental health disorder, 180 (58 percent) for substance abuse, and the remaining 23 (7 percent) for both mental health problems and substance abuse.

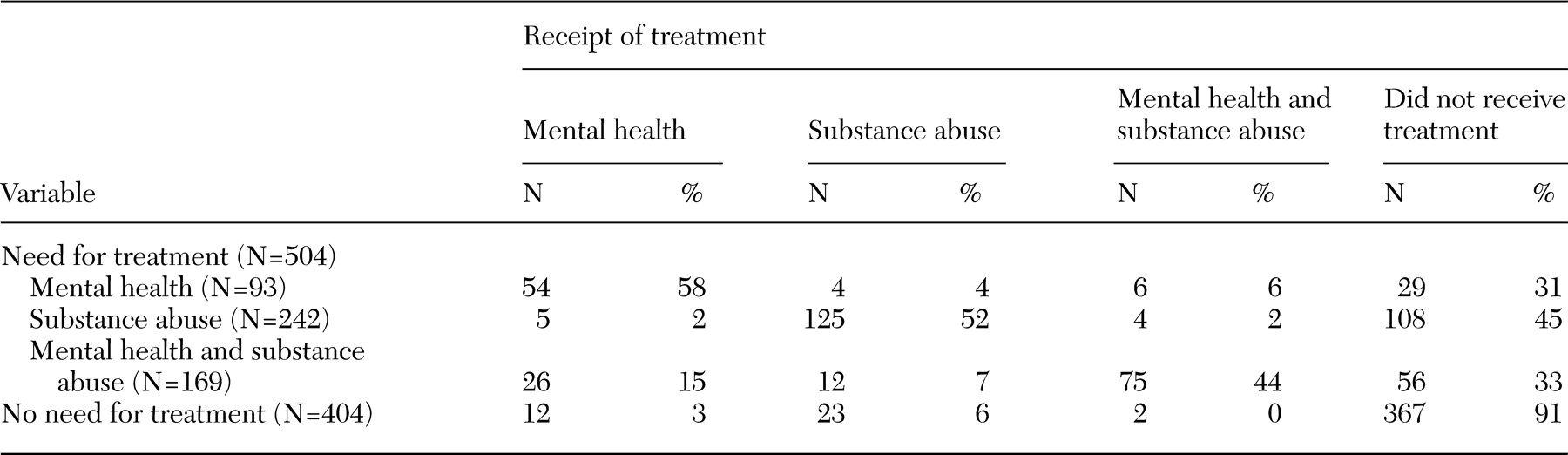

However, the rate at which treatment was engaged within this population before incarceration varied by type of treatment, as shown in

Table 1. More than half (58 percent) of the 93 respondents who reported needing treatment for mental health problems before incarceration actually received this type of treatment. Similarly, about half (52 percent) of the 242 respondents who needed treatment for substance abuse received this treatment, compared with 44 percent of the 169 respondents who needed treatment for comorbid mental health and substance use problems received treatment for both. More important, the findings indicate that 30 to 45 percent of the women in each category did not receive any form of treatment in the two years before incarceration.

Logistic regression was used to predict the likelihood of receiving a particular type of treatment (mental health, substance abuse, or both) for the 504 respondents who reported needing treatment during the two years before incarceration. The results of these analyses showed that in all cases eligibility for health insurance coverage was the only factor with a statistically significant main effect on the likelihood of receiving treatment. Specifically, among respondents who needed treatment for mental health problems before incarceration, women who had health insurance were three times as likely as those who did not to receive the treatment they needed (odds ratio [OR]=3.1, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.4 to 7.5, p<.001). Among respondents who needed treatment for substance abuse, those who had health insurance were twice as likely as those who did not to receive such treatment (OR=2.3, CI=1.3 to 3.7, p<.005). Finally, among women who needed treatment for comorbid mental health and substance use problems, those who had health insurance were four times as likely as those who did not to receive both types of treatment (OR=4.1, CI=2.03 to 8.7, p<.001).

Changes in treatment needs between community and prison

Respondents' perceived need for behavioral health treatment before and during incarceration was examined next. The first set of findings is based on comparisons of perceived need for specific types of treatment before and during incarceration. The next set reflects comparisons in perceived need for specific types of behavioral health treatment in prison by those who had received particular types of treatment in the community.

First, self-assessed need for behavioral health treatment before and during incarceration was found to vary by type of problem. Respondents with mental health problems were more likely than those with substance abuse only to report needing treatment for these problems in the community and in prison. Specifically, 60 of 93 women (65 percent) who reported a need for mental health treatment while living in the community also reported needing similar treatment in prison. Adding substance abuse increased the consistency in self-assessed need; 145 of 169 women (86 percent) reported a need for treatment for comorbid mental health and substance abuse before and after incarceration. By contrast, only 97 of 242 (40 percent) who reported a need for treatment for a substance use disorder before incarceration said they needed such treatment in prison.

Second, changes in the pattern of treatment needs were also apparent for respondents who received behavioral health treatment before incarceration. Among the 97 respondents who were treated for mental health problems before incarceration, 53 (55 percent) reported needing the same treatment in prison. However, of the 164 respondents who previously received substance abuse treatment, 40 (24 percent) reported needing the same treatment in prison. Just over half the respondents who received treatment for comorbid mental health and substance abuse before incarceration reported needing the same combination of treatment in prison (47 of 87 women, or 54 percent).

The overall pattern emerging from these findings, then, is one of significant reductions (60 to 75 percentage points) in the percentage of respondents who reported a need for substance abuse treatment in prison compared with the percentage who reported such a need before incarceration. Somewhat more modest reductions (25 to 45 percentage points) were found in the percentage of respondents who needed treatment for mental health or comorbid mental health and substance use problems in prison, compared with the percentage of those who needed such treatment before incarceration. Yet 60 of 404 respondents (15 percent) who reportedly did not need any treatment before incarceration reported needing treatment in prison, mostly for mental health problems. Furthermore, 51 of 169 (30 percent) who previously required treatment for a comorbid mental health and substance use problem needed only mental health treatment in prison, and 48 of 242 (20 percent) who were treated for substance abuse before incarceration needed mental health treatment or a combination of mental health and substance abuse treatment in prison.

Match between needs and treatment in prison

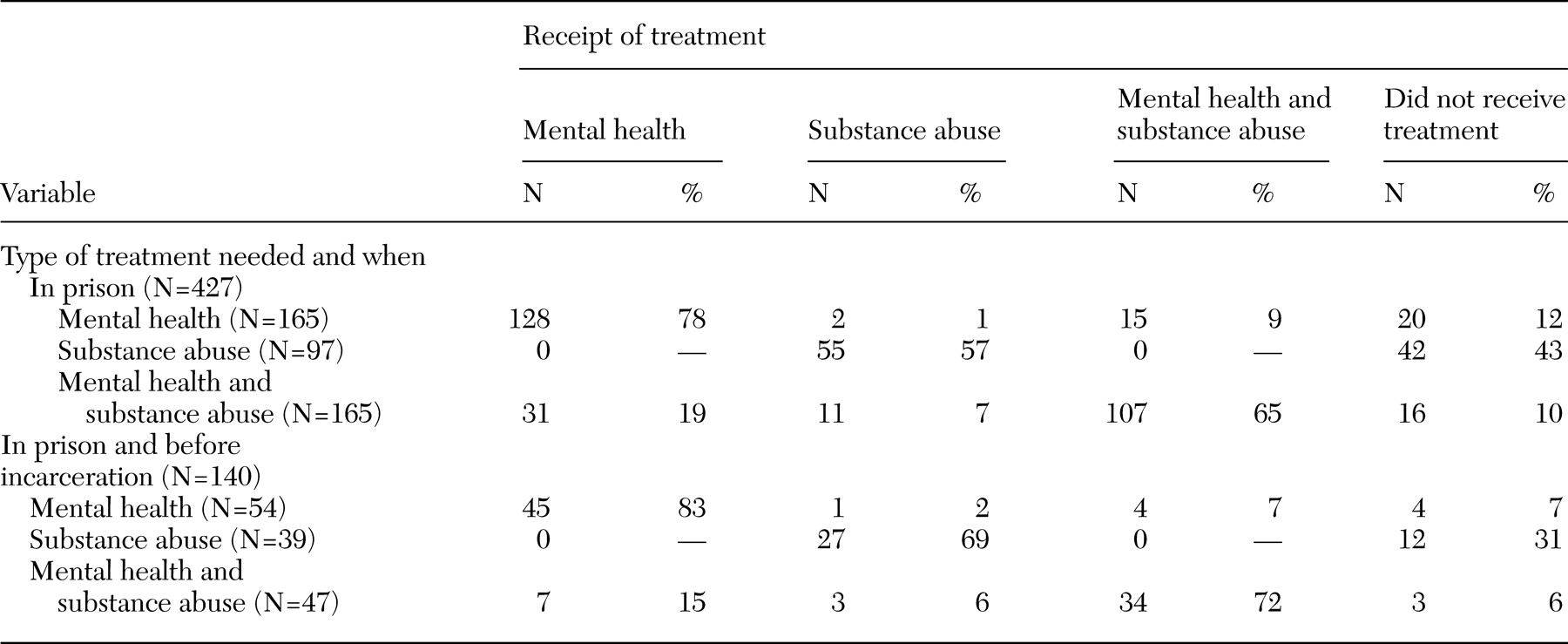

To explore the effect of prison on the ability to gain access to treatment and the continuity of treatment, two specific subgroups of respondents were analyzed: all female inmates who reported a need for treatment in prison, regardless of whether they also needed treatment before incarceration (N=427), and all female inmates who received behavioral health treatment before incarceration and reported needing the same treatment in prison (N=140). Findings are presented in

Table 2. Similar information is also provided for a relatively small group of women (N=57) who needed but did not receive behavioral health treatment before incarceration and continued to need such treatment in prison.

Compared with the rate of match between need for and receipt of treatment for respondents before incarceration (

Table 1), the rate for the same subpopulation in prison was higher for all three types of behavioral health treatment (three left columns in

Table 2). That is, although 58 percent of respondents reported needing and receiving treatment for mental health problems before incarceration, 78 percent reported needing and receiving such treatment while in prison. Similarly, 52 percent of respondents reported needing and receiving treatment for substance abuse before incarceration, and 57 percent reported needing and receiving such treatment while in prison. Finally, 44 percent of respondents reported needing and receiving treatment for comorbid mental health and substance use problems before incarceration, and 65 percent reported needing and receiving this type of treatment in prison.

The three columns on the right in

Table 2 present data on continuity of behavioral health treatment for respondents who received treatment before incarceration (N=140) and who assessed themselves as still needing this type of treatment while in prison. A vast majority of these respondents continued to receive the same type of treatment in prison as they had received in the community. These findings suggest that prison did not disrupt the type of behavioral health treatment that they had received in the community.

Discussion

A majority of inmates in the women's state correctional facility in New Jersey who thought they needed behavioral health treatment reported that they received the treatment while in prison. In fact, female inmates who participated in this study reported having better access to treatment in prison than in the communities where they lived before incarceration. In this respect, the correctional system seems to reduce the treatment disparities that exist outside of prison and, for the most part, begins the process of continuous behavioral health treatment while women are in prison. This finding may be explained, in part, by the fact that receiving treatment in prison may not be voluntary in that parole decisions depend on participation in treatment, whereas women who live in the community can choose to decline treatment without criminal justice sanction. Still, the rate of match between need for and receipt of treatment in prison was not uniform across types of treatment. Mental health treatment was the need most often identified by the women in the New Jersey prison system (262 women, or 29 percent of the sample), and well over 80 percent of the women in our study who needed this type of treatment in prison reportedly had received it. In contrast, 45 percent of the 242 respondents who reportedly needed treatment for substance abuse problems did not receive such treatment in prison.

Although these results suggest that behavioral health treatment is more readily accessible to women in prison than in the community, they must be interpreted cautiously. First, given the constraints involved in gaining access to prison populations, the only feasible way to estimate need was through self-reports. These self-reports of perceived need were not corroborated with clinical records. Thus we cannot assess the accuracy of respondents' perceptions of their treatment needs. Those who reported a need for mental health treatment may not meet the conditions of clinical need; likewise, those who did not report a need may meet the clinical threshold. As a consequence, these findings cannot be used to assess the appropriateness of treatment assignment before or during incarceration. However, past research has shown that self-reports of mental illness can be quite accurate and reliable, particularly when the questions asked are general (

18,

19). Moreover, even if self-reported perceptions were biased in some systematic way from a clinical assessment, there is no reason to believe that self-reports of treatment needs and delivery of treatment before incarceration will be any more or less biased than self-reports of treatment needs and delivery of treatment in prison. Therefore, interpretations of these results are most likely to be valid when framed in relative terms and in terms of access to services. Particularly, these findings suggest that behavioral health providers may be more responsive to the perceived needs of these women when the women were inmates than when they were in the community.

However, this finding may not generalize to female inmate populations in other states. Gaining access to treatment is dependent on the relative delivery and financing of behavioral health treatment in the community and in prison. States with more overburdened or underdeveloped community-based mental health systems would be expected to have relatively lower rates of access than their counterparts in the prison system, as observed in this study, in part because mental health treatment is a constitutional right of inmates (

20,

21,

22,

23,

24). Although New Jersey's trend of incarcerating women is similar to the trend observed at the national level (

25), the rate of diagnosed mental disorders among female inmates in New Jersey is higher than that found among female inmates nationwide (37 percent compared with 25 percent), reflecting in part the comprehensive screening for mental health problems in New Jersey prisons. Similarly, states, such as New Jersey, that are under consent decrees or court settlements resulting from class action suits related to the inadequacy of mental health treatment inside prisons are more likely to have relatively higher rates of access to treatment in prison. In general, the rates of access and the magnitude of the difference between need for and receipt of treatment will depend on the relative availability of behavioral health treatment inside and outside the prison and the methods used to ration access.

Conclusions

Prison appears, at least in New Jersey, to improve access to behavioral health care. On the one hand, this finding is consistent with the rehabilitation goals of incarceration, in which this opportunity of confinement is used to prepare the person to reenter the community. Getting ready for reentry includes getting healthy. On the other hand, if treatment had been provided in the community, especially for substance-related problems, prison may have been avoided. This finding alone should motivate policy makers to take swift steps to ensure that the criminal justice system does not become the more reliable behavioral health care system for the poor.

Although the evidence on the ability to gain access to mental health treatment in this state prison is positive, it raises the question of quality: What types of treatment are available? Is treatment continuous? Does treatment address previous victimization and its connection to mental health or substance abuse problems? Is treatment more than the administration of medications? These issues need to be addressed next in future research.

The less positive finding concerns the limited access to substance abuse treatment, which is problematic because at least half the women in state prisons were under the influence at the time of their offense and most women are in prison on drug-related convictions (

2). It seems particularly important to engage women in treatment for these problems while they are away from the environments that encourage such behavior. Missing this opportunity to intervene is particularly shortsighted in light of the number of women who return to prison on parole violations for positive drug screens or new drug charges. Perhaps it is time for the courts to rethink their position on substance abuse treatment as a constitutional right.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by grant P-20-MH-66170 from the National Institute of Mental Health.