Our laboratory, and others, have shown that a history of abuse is related to 1) increased electrophysiological abnormalities, predominantly in the left frontotemporal region

5; 2) a higher prevalence of ictal temporal lobe epilepsy-like symptoms

6; 3) abnormally elevated left hemisphere EEG coherence

7; 4) reduced volume of the left hippocampus

8–11; 5) smaller size of the corpus callosum

12–15; 6) alterations in the paramagnetic properties of the cerebellar vermis

16; 7) abnormalities in cortical size, symmetry, and neuronal density

17–20; and 8) highly lateralized hemispheric responses to memory recall.

21 Together, these findings, and others, support the hypothesis that abuse has a deleterious effect on brain development.

DISCUSSION

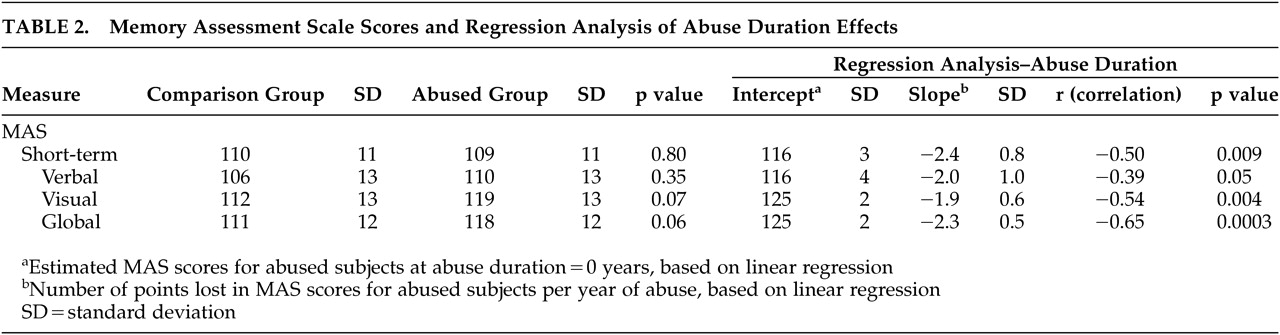

Differences emerged between healthy female college students with no history of trauma or psychiatric illness and a community sample of young adult college women with childhood sexual abuse in inhibitory capacity, memory functions, and scholastic aptitude. A number of factors must be considered when interpreting these findings and comparing them with previous reports. First, we selected subjects with childhood sexual abuse without regard to psychiatric symptoms. Although childhood sexual abuse is a substantial risk factor for later psychopathology,

37,38 many children exposed to such abuse never develop any psychiatric condition in general nor PTSD in particular.

39,40 Recruitment of abused subjects without regard to psychiatric illness avoids the possibility (discussed in the introduction) that observed alterations were not a consequence of the maltreatment but a risk factor for PTSD or other prespecified diagnosis.

23A second, important aspect of this study was that all of the recruited subjects were college students. Further, they were unmedicated, had no significant history of alcohol use, and had no other exposure to traumatizing events. Studies of older adults are often complicated by varying degrees of drug or alcohol use and by a lifetime history of exposure to other traumatic experiences. Subjects in this study also had a history of repeated, forced, and unwanted sexual contact, but penetration was not required for enrollment. Forced penetration may be an important factor related to the degree of adverse psychiatric outcome.

41,42Overall, these selection criteria biased the sample to include a substantial number of less traumatized subjects with good psychiatric health and above-average cognitive capacity. Subjects were intentionally recruited in this manner to provide a rigorous challenge to the hypothesis that childhood sexual abuse is accompanied by neuropsychiatric and neurocognitive abnormalities. Hence, observed differences between the abused sample and healthy comparison subjects are particularly compelling.

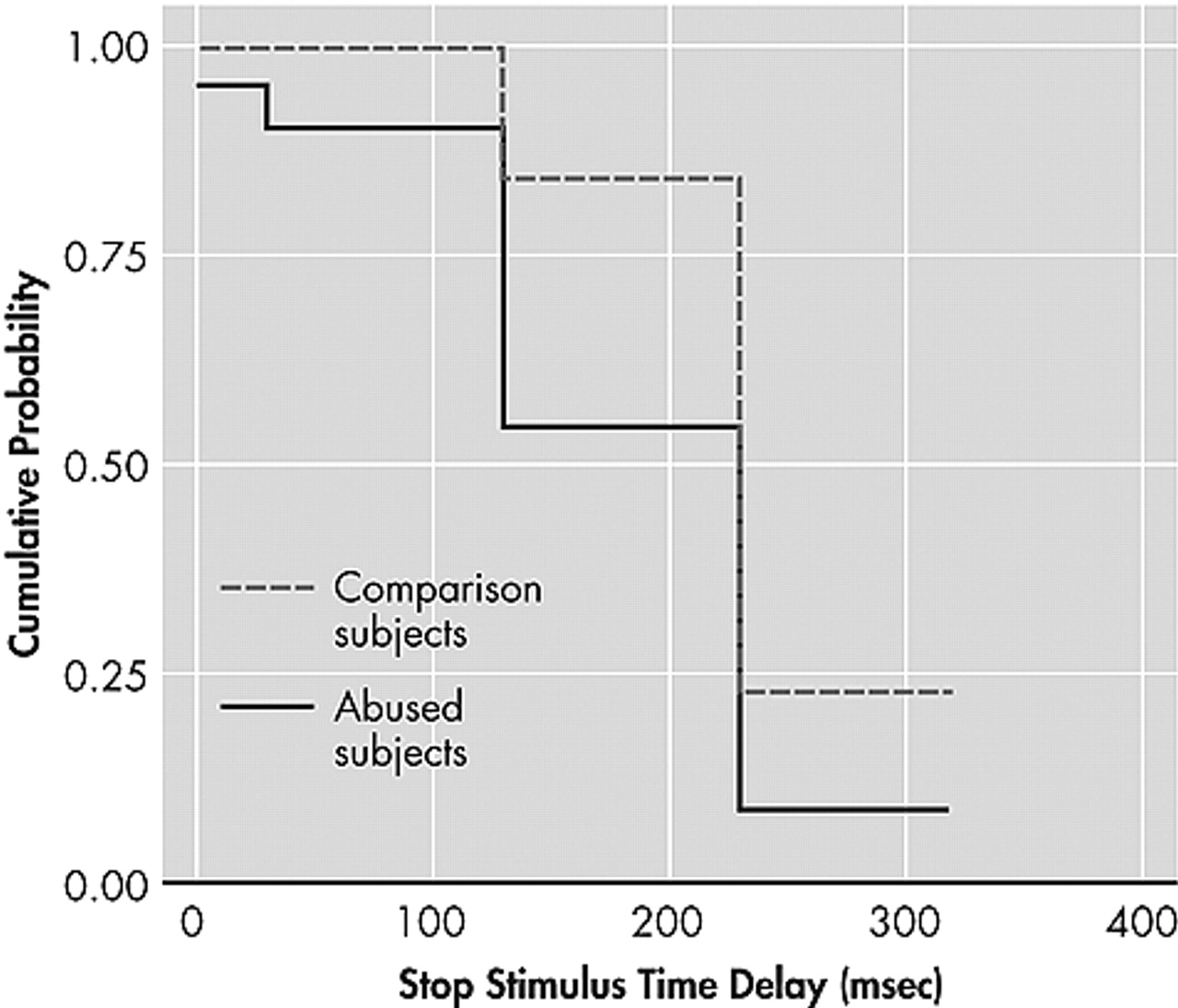

These findings are in accord with some previous reports. First, diminished inhibitory capacity was reported by Mezzacappa et al.

2 using a GO/NO-GO/STOP continuous performance task. Their sample consisted of abused boys who were enrolled in therapeutic schools for children with emotional and behavioral problems. The present study suggests that alterations in inhibitory capacity may transcend age, sex, and educational setting.

Abused subjects in the present study had deficits in inhibitory capacity, but no evidence emerged of impaired sustained attention or distractibility on the continuous performance task. Beers and De Bellis

4 found that abused children performed more poorly on measures of freedom from distractibility and sustained visual attention. However, they focused specifically on abused children with PTSD and used different means to study attention.

Various cognitive deficits have been reported in several studies, including short-term memory deficits,

1,43 and lower levels of intellectual ability, academic attainment, abstract reasoning, and executive function.

4,44,45 Koenen et al.

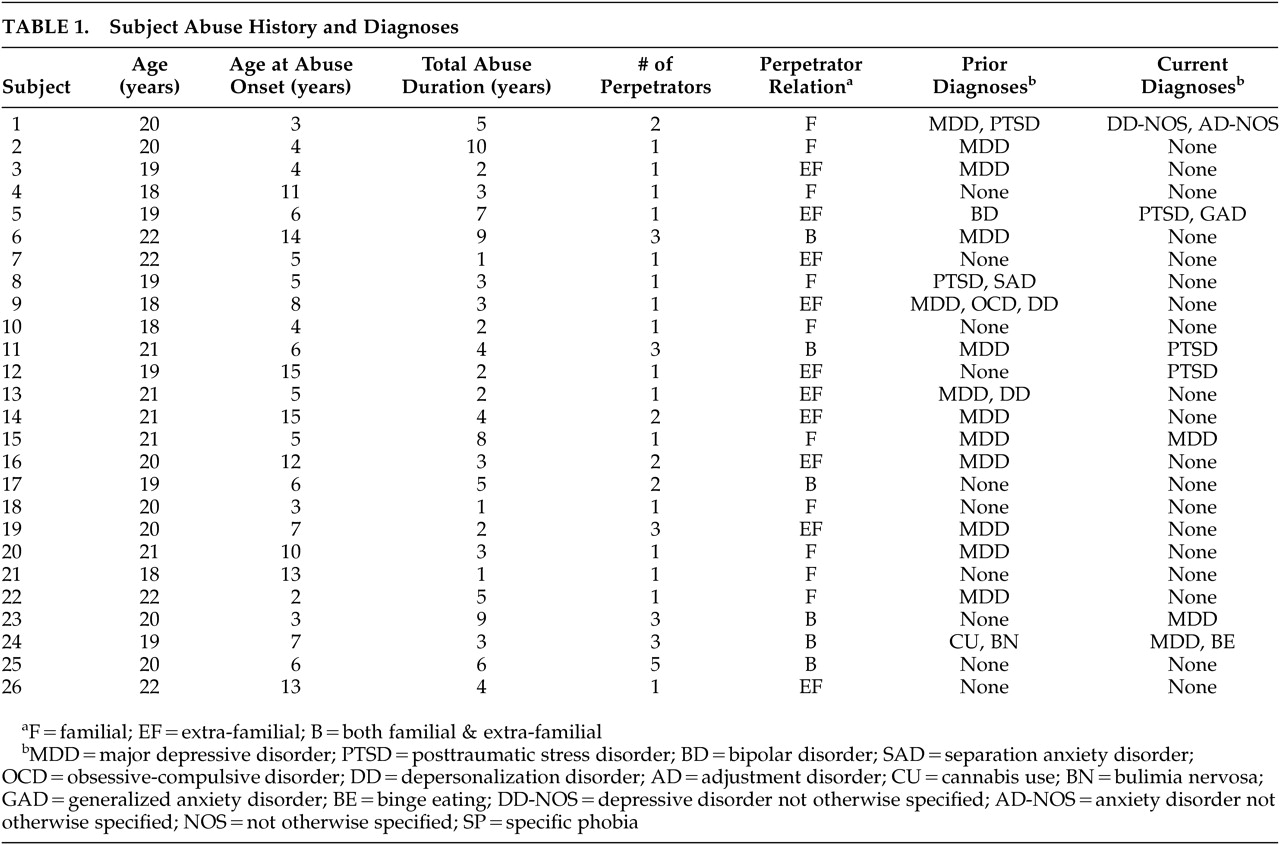

46 found that children exposed to high levels of domestic violence had intelligence scores that were lower than unexposed children and that domestic violence was associated with a dose-dependent intellectual decline independent of latent genetic influences. Similarly, we found a strong graded association between duration of childhood sexual abuse and memory function. No overall difference between abused subjects and the contrast group was found because the majority of subjects had a relatively short duration of abuse. Abused subjects with the most profound memory impairments are probably unlikely to matriculate. It should be noted that extrapolating scores for the abuse group back to the zero abuse point (regression intercept) yields mean MAS scores 3.6% to 9.8% greater than comparison subjects (

Table 2). If it were true that childhood sexual abuse produces a duration-dependent decrease in memory function, then some of the abused subjects might have had high MAS scores if they had never been abused. This does not imply that individuals with superior memory abilities are at greater risk for abuse, but that by attenuating memory ability abuse may reduce an individuals’ likelihood of attending college, suggesting that those who attend may have had greater than average innate ability.

The selective deficit in math SAT scores in the abused group is interesting, as is the observation that abused subjects had a significant correlation between their verbal and math SAT scores whereas comparison subjects did not. Imaging and lesion studies have provided strong evidence for the involvement of left frontal regions in mathematical abilities.

47–50 However, evidence also exists for bilateral processing with the two hemispheres contributing different capabilities. For instance, the whole left dorsolateral frontal cortex was activated when a verbal strategy was used to perform subtractions, whereas both right and left prefrontal regions were activated when a visual imagery strategy was utilized.

51 Dehaene et al.

52 demonstrated that exact arithmetic is left lateralized and recruits networks involved in word-association processing, but approximate arithmetic shows language independence, relies on a sense of numerical magnitudes, and recruits bilateral areas of the parietal lobes involved in visuospatial processing. The math SAT questions focus on algebra, geometry, and magnitude estimation and have been designed so that they can be answered correctly using both exact and approximate approaches.

With these considerations in mind, we hypothesize that the lower math SAT scores of the abused sample could stem from a defect in hemispheric integration. Schiffer et al.

21 found that subjects with a history of childhood abuse predominantly activate their left hemisphere while recalling neutral material, and predominantly activate their right hemisphere when recalling disturbing personal events. Hence, subjects with a childhood abuse history may be strongly reliant on left hemisphere function during the SAT, and may be less able to utilize more right hemisphere-based visuospatial mathematical skills that could enhance test performance. The hypothesized reliance of abused subjects on left hemisphere-based mathematical skills involved with word-association is consistent with the observation that math and verbal SAT scores were correlated in the abused group but not in the comparison subjects. Reduced hemispheric integration may be a consequence of reduced corpus callosal area that has been observed in abused children.

12–15There are several significant limitations to this study. First, these subjects were less symptomatic and possibly less severely affected by childhood sexual abuse than subjects in other studies. One reason for this is that we limited the abused sample to subjects who had experienced childhood sexual abuse as their only traumatic experience. Exposure to disparate traumatic events is a common occurrence, and it appears to exert an additive or even synergistically deleterious effect.

6 Limiting the sample in this way, however, provides strong evidence that identified group differences are related to childhood sexual abuse and not to another type of maltreatment, nor to the interaction of exposure to multiple traumas.

Second, there is the relatively narrow focus of the instruments utilized. We intentionally limited testing to instruments for which we had specific predictions and chose not to include a comprehensive test battery to avoid the statistical problems that accompany global explorations. The results of the present study show that neurocognitive differences exist that are consistent with observations made using imaging and electrophysiological techniques. They do not, however, detail the full breadth of possible neuropsychological differences.

The third limitation is the use of self-report for SAT scores. Subjects were not required to provide official documentation as proof of their SAT performance. However, the potential validity of self-report SAT scores is supported in the literature. For example, in a sample of predominantly white women, Cassady

53 found quite high correlations between self-report and actual performance for the SAT total score (r = 0.88, p=0.0001), verbal scale (r = 0.73, p=0.0001), and math scale (r = 0.89, p=0.0001). Nonetheless, our preliminary finding of greatly diminished SAT math scores of the abused group needs to be replicated in a separate sample by directly evaluating mathematical abilities with a standardized achievement test.

The fourth limitation is the exclusive focus on young women. Several studies suggest that early maltreatment may exert an even more deleterious effect on men.

13,15 Further research is needed to ascertain whether boys exposed to childhood sexual abuse show the same constellation of neuropsychological differences in adulthood. It must also be noted that associations between childhood sexual abuse and altered neurocognitive function are correlational. We cannot exclude the possibility that these subjects had preexisting abnormalities that increased their risk of being sexually abused, although it is difficult to imagine very young children bringing forth their own sexual abuse.

The fifth limitation is that the onset of abuse occurred during widely different stages of neural development. We have speculated that a given brain region is most vulnerable to insult (e.g., traumatic stress) during phases of most rapid development.

54,55 Accordingly, we have preliminary data suggesting that childhood sexual abuse during early childhood has a negative impact on gray matter volume of more primitive brain regions whereas later childhood sexual abuse (e.g., adolescence) affects primarily neocortical areas. However, many brain regions, including the corpus callosum,

56 hippocampus,

57 and frontal regions,

58 gradually myelinate over decades and this process appears vulnerable to the effects of stress. Myelination depends on glial cell division,

59 which occurs throughout life, and stress hormones suppress the critical final mitosis of granule cells from proliferative precursors into postmitotic Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes

60 that form the myelin sheath. Hence, duration of abuse may be a more critical factor influencing white matter development than age of abuse, and can provide an explanation for why abuse at different ages might exert similar effects on certain neurocognitive measures.

Last, we speculate that the observed math deficit and relative deficiency in visuospatial span in childhood sexual abuse subjects is analogous to individuals with nonverbal learning disabilities, specifically arithmetic learning disabilities.

61 That is, both are presumed to have problems with right-hemispheric processing. We further speculate, however, that the apparent right hemisphere deficiency in childhood sexual abuse subjects is more directly related to a disruption in right-left hemisphere integration,

61 which may be a consequence of early stress effects on the developing corpus callosum.

15,19,62 If this were true, then it might follow that these individuals would benefit from efforts to foster right-left hemisphere integration. We have postulated that this might be possible through training in tasks that normally require precise right-left hemisphere interactions, such as learning a musical instrument.

63 Schiffer

64 has been working on an alternative approach using lateral visual field stimulation to preferentially activate right versus left hemispheric cortical regions,

65 which he has found useful in fostering integration in the course of psychotherapy. Overall, this study provides additional evidence that childhood sexual abuse is associated with neurocognitive abnormalities, and that these abnormalities are discernible in a healthy collegiate sample, are not a consequence of differences in socioeconomic status, or attributable to residual symptoms of depression, anxiety, or PTSD.