N europsychiatrists are often called upon to evaluate individuals with psychotic symptoms for possible neurological or neurodevelopmental etiologies. The diagnosis of acquired neurological disorders, while not always straightforward, is most familiar to general adult neuropsychiatric practitioners. In contrast, a bewildering array of relatively rare congenital neuropsychiatric conditions that include psychosis have been described. Although some reviews of congenital disorders that include psychosis have been published,

1 –

4 clear guidance on the neuropsychiatric evaluation and differential diagnosis of these conditions can be difficult to find. To address this dearth of information, we set out to concisely describe the congenital disorders that may include psychosis, and propose a straightforward neuropsychiatric approach to their differential diagnosis based on major associated signs and relative prevalence of the disorders. Guidance on laboratory and neurodiagnostic evaluation is offered for each disorder, along with a list of known genetic loci.

METHODS

We conducted a literature search for disorders that may present with psychosis, utilizing PubMed and Ovid, with search terms including “psychosis” paired with “metabolic,” “genetic,” “congenital,” and “neurodevelopmental.” All disorders described in case reports or case series and literature reviews, including their references, were initially included. Disorders were then excluded if fewer than three published case reports with adequately described psychotic symptoms could be identified, or if due to nonheritable or noncongenital disorders. Descriptors of psychotic symptoms included such terms as “hallucinations,” “delusions,” “schizophrenia-like,” and “schizophreniform,” as well as known psychotic syndromes such as “Capgras syndrome.” To focus the review on disorders that could present in the typical age range for major axis I psychotic disorders, disorders that typically present beyond age 50 were excluded. Standard neurology and neuropsychiatric textbooks were consulted for additional information about the included disorders.

5 –

9Disorders were categorized by the presence of one or more of 20 prominent groups of associated signs with an emphasis on those of major neurological significance. Group assignment was limited to those associated signs judged to occur commonly in each disorder. Disorders with unique phenotypic features that can be recognized easily were identified. Epidemiological information was gathered via OMIM,

10 GENETests,

11 and Orphanet

12 and disorders were classified by prevalence into three groups: more common (prevalence >1/10,000), rare (prevalence 1/10,000–1/50,000) and extremely rare (prevalence <1/50,000).

RESULTS

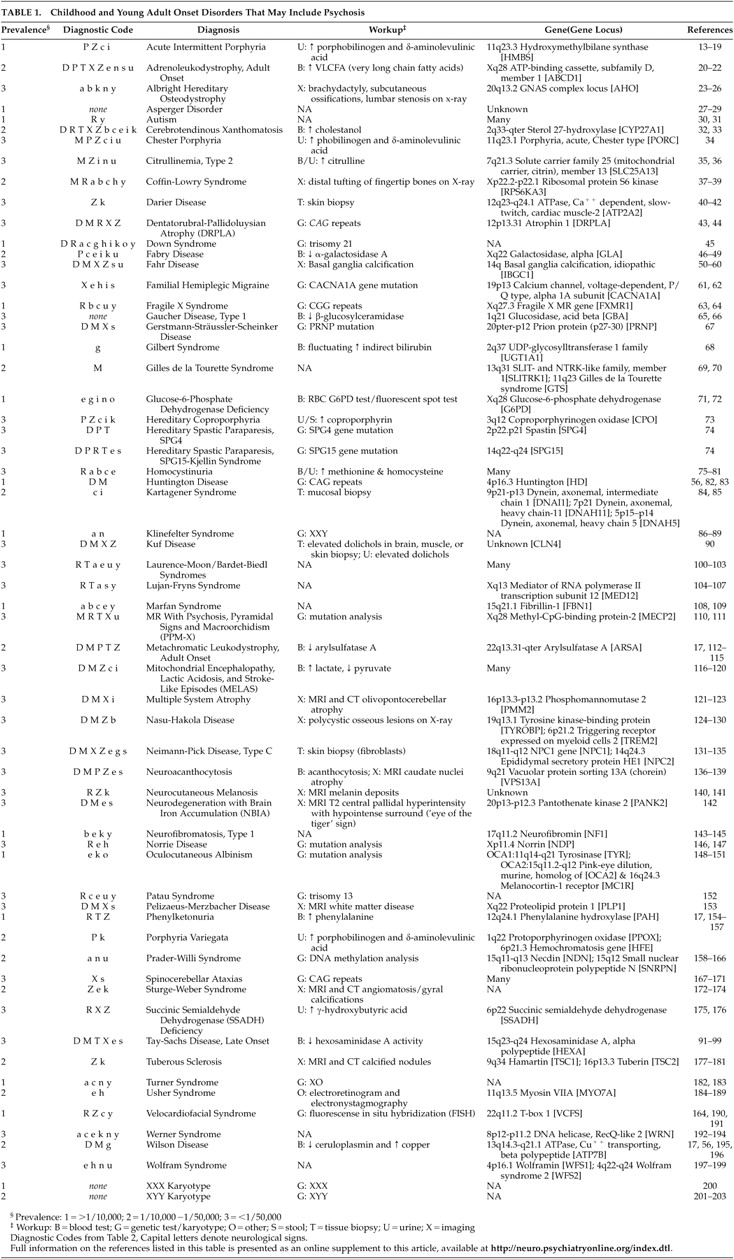

We identified 62 congenital disorders that may present from childhood through middle-age and include psychosis (

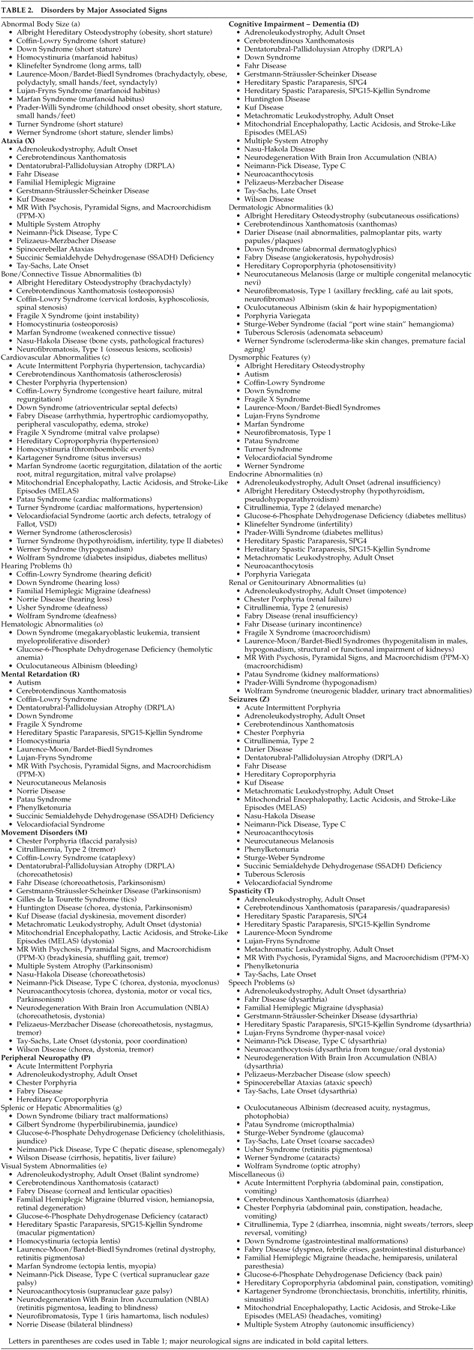

Table 1 ). Prominent associated neurological and physical sign groups are listed in

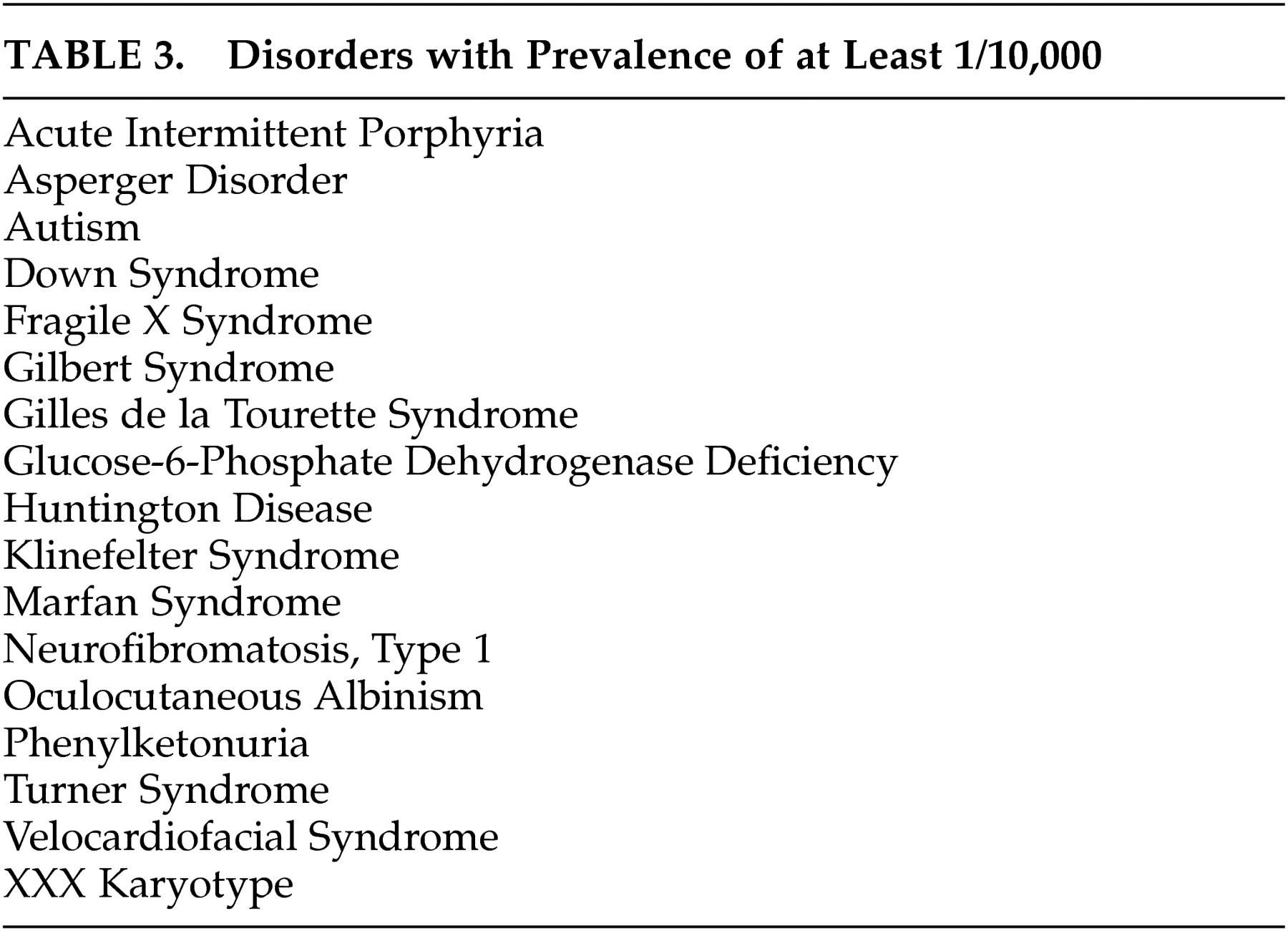

Table 2 . Forty-four disorders (71%) have prominent associated neurological features that facilitate differential diagnosis. Seventeen disorders (27%) have readily recognizable unique phenotypes. Forty-five disorders (73%) may present without mental retardation. Fifty-three disorders (86%) have characteristic laboratory features. Fifty-three disorders (86%) have known genetic loci or several different etiologies with known loci (e.g., autism), and three disorders (5%) have loci yet unknown. Five disorders (8%) were due to chromosomal nondisjunction. Sixteen disorders (26%) have estimated prevalence of 1/10,000 or greater (

Table 3 ).

DISCUSSION

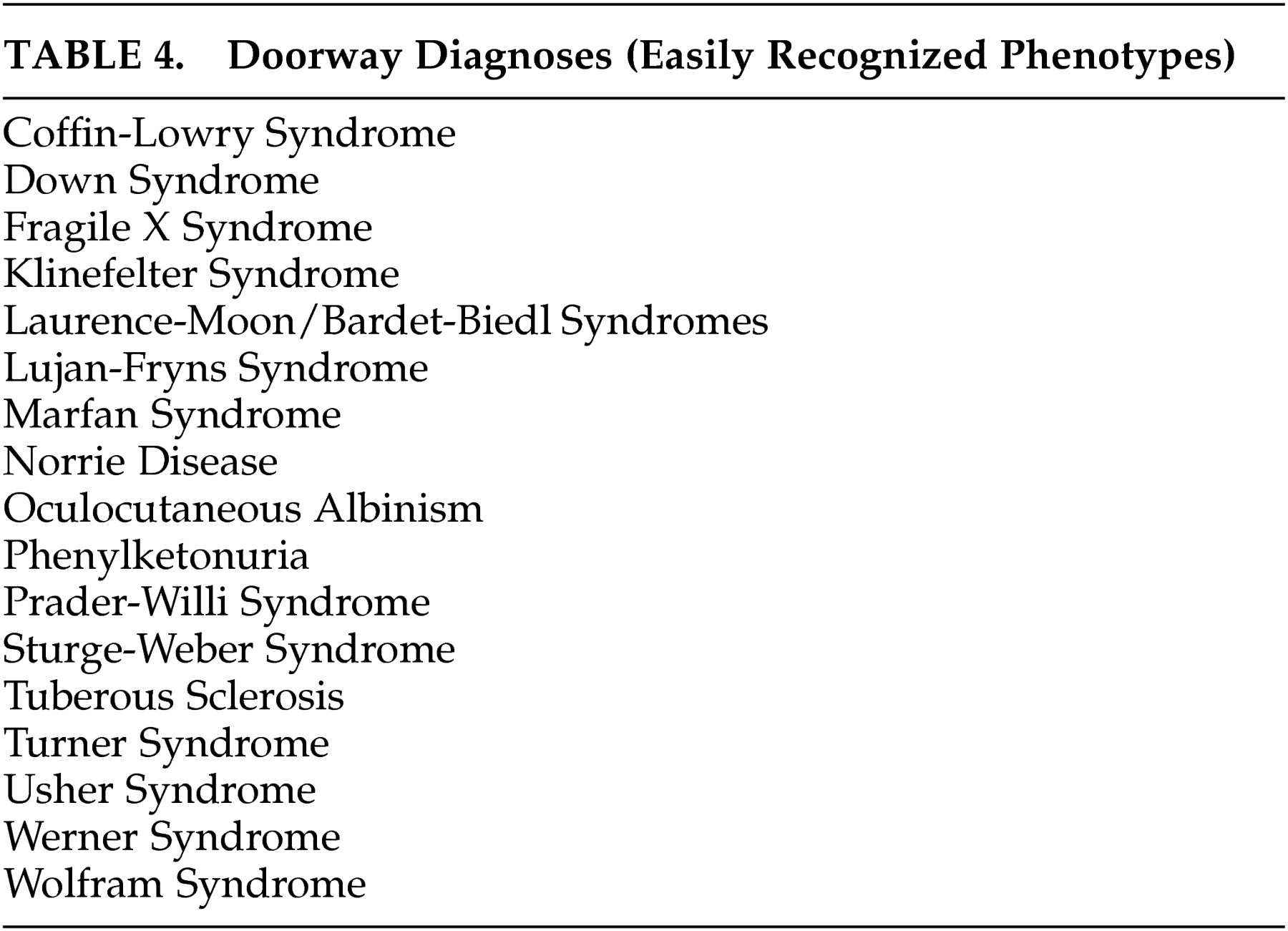

A neuropsychiatric diagnostic approach that takes relative prevalence into account is suggested to simplify a differential diagnosis that includes a large number of rare disorders. The diagnosis of unusual disorders that can present with psychosis receives little if any attention in psychiatry or neurology residency training. Although most of these disorders are unlikely to present to psychiatrists or neurologists more than occasionally, the failure of physicians to recognize them may lead to unnecessary delay in diagnosis, misdiagnosis, or missed opportunities to offer genetic counseling. Furthermore, failure to recommend appropriate treatment or application of inappropriate treatment may lead to adverse outcomes. A substantial minority of these disorders have prominent unique phenotypes that are readily recognizable at a distance, which we have called “doorway diagnoses.” These are listed in

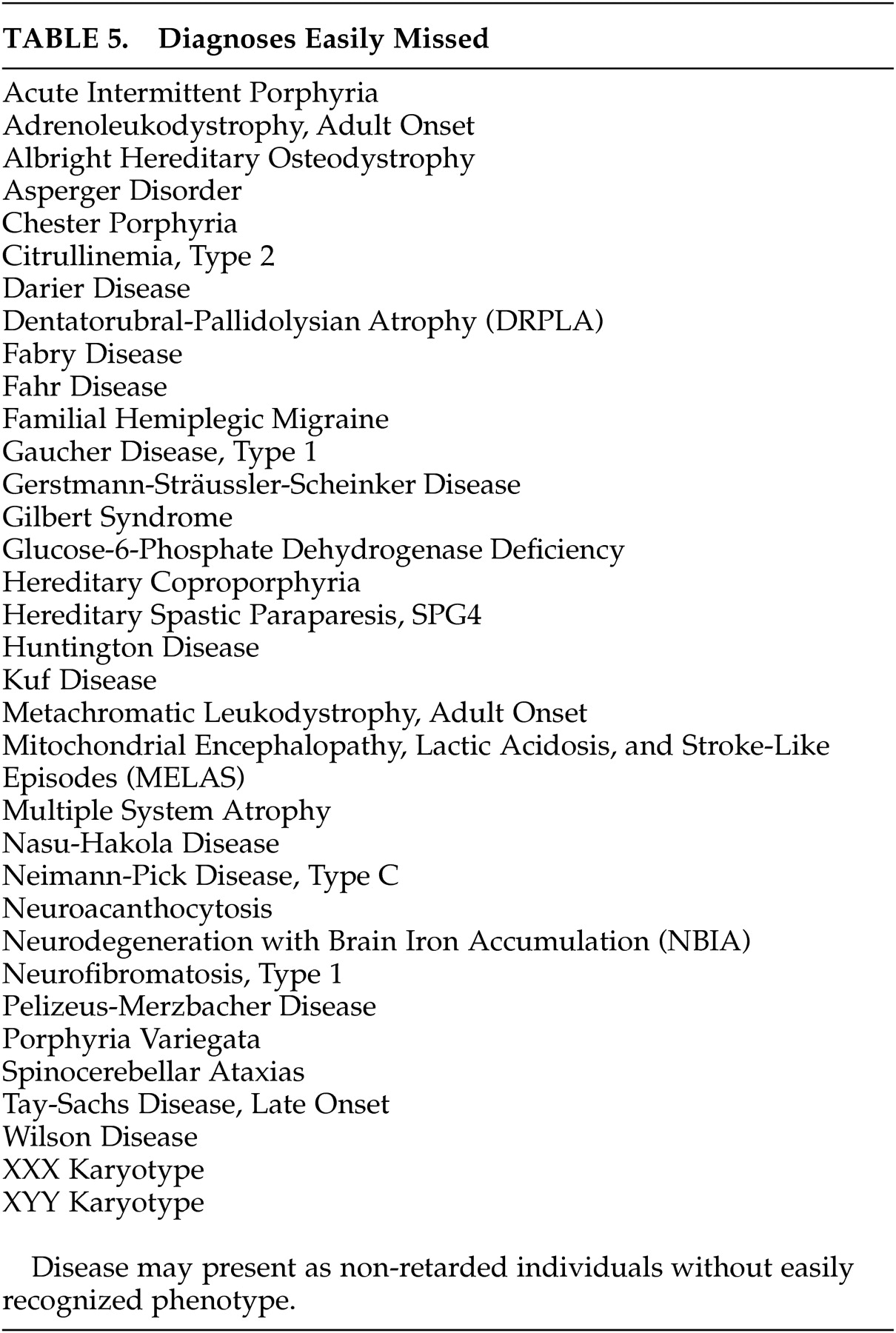

Table 4 . Fifty-five percent of disorders identified have subtypes that present without mental retardation or easily recognized phenotypes and are thus easily missed (

Table 5 ).

It would be cost-prohibitive to order a laboratory and neurodiagnostic workup to rule out all of the possible causes of psychotic symptoms, even if that workup were reserved only for those disorders whose natural history is atypical for major axis I psychotic disorders. A coherent neuropsychiatric approach, such as the one presented here, improves cost management by providing a probability-guided, examination-based approach to focus the diagnostic workup.

Identification by literature review of disorders that have been reported to include psychotic symptoms is a first step and may be diagnostically useful, but presents a number of confounding variables that should be addressed. With the exception of the more common disorders, it would be difficult to assemble large enough populations with a given diagnosis over sufficient time to carefully study their psychotic symptoms. Whether the psychotic symptoms are directly caused by the disorder, are a common behavioral response to environmental or medical stress, or are merely coincidental cannot be determined from these reports. Despite the inclusion of misleading terms such as “schizophreniform,” “schizophrenia-like,” or “manic” in many case reports, the histories of many of the reported disorders do not appear to be consistent with axis I disorders such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar mania, or major depression with psychotic features, despite phenotypic similarity at the time of presentation. Few congenital disorders have been described that closely resemble schizophrenia. Metachromatic leukodystrophy, which has both negative and positive signs and symptoms and may begin within the typical age range of schizophrenia onset, is one such disorder. Velocardiofacial syndrome, which typically progresses from mood disorder to schizophrenia-like disorder and may account for up to 6% of childhood-onset schizophrenia, is another.

Another potential limitation of this review arises from reliance upon the most common presentations to determine the major associated neuropsychiatric signs. For example, although neurofibromatosis type 1 certainly may be a cause of seizures, seizures are estimated to occur only in 7% of affected individuals; therefore, neurofibromatosis type 1 was not included in the seizure group.

Studying neuropsychiatric disorders of known etiology that include psychosis may ultimately lead to research aimed at understanding the etiology of psychotic symptoms in axis I disorders. With recent improvements in DNA analysis, genes have been identified for the majority of these disorders, many of which are causative for the disorder and not merely associated with one subtype or susceptible population. As genotyping becomes less cost-prohibitive and more commonly available, neuropsychiatrists will need to develop increased sophistication with the utilization of genetic tests in the differential diagnosis of psychosis.

CONCLUSION

As consultants frequently called upon to evaluate atypical presentations of psychosis, neuropsychiatrists should be aware of congenital disorders that can present with psychosis, however rarely. To minimize missed diagnoses, both general psychiatrists and neuropsychiatrists should become familiar with the phenotypes of the 17 “doorway diagnoses” we have listed (

Table 4 ). We recommend a differential diagnostic approach based on estimated prevalence of the disorders and their most prominent associated neuropsychiatric and physical features, to facilitate appropriate diagnosis in a systematic and cost-effective fashion.

Acknowledgments

Poster presented at the American Neuropsychiatric Association Annual Meeting in Tucson, Ariz., February 18–20, 2007.