Sample

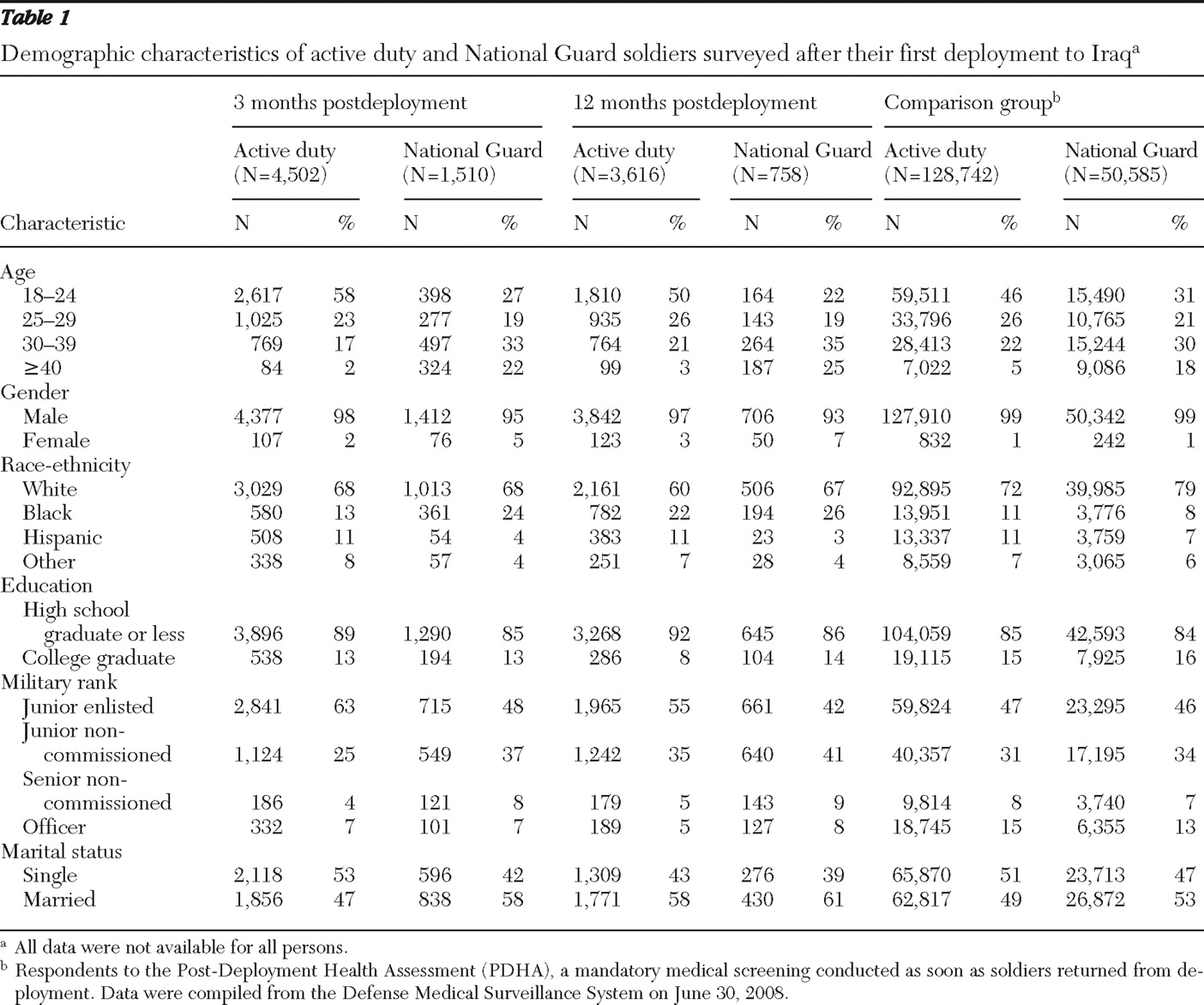

A total of 15,918 anonymous surveys were received from both components (active duty and National Guard) and from both time points (three and 12 months). Of these, 10,386 reported being deployed to Iraq and were included in the analysis. All data were collected cross-sectionally from multiple brigade combat teams between December 2003 and October 2007. A total of 1,510 National Guard soldiers and 4,502 active duty soldiers were surveyed three months after their first deployment to Iraq. An additional 758 National Guard soldiers and 3,616 active duty soldiers were surveyed 12 months after their first deployment. Because a majority of soldiers remain in the unit from which they were deployed for the next 12 months, it is likely that many of the same soldiers completed surveys at both time points. In each of the units at both time points, unit personnel reported that 27,005 soldiers were available to participate in the study. This yielded an overall response rate of 59% (N=15,918 of 27,005), which is consistent with other military population-based studies (

1,

10 ). Reasons for not being able to attend the survey session include work-related duties and being on leave, ill, or on temporary duty elsewhere. Among those who were present for the study, approximately 94% to 99% of soldiers from both time points and components completed any part of the paper-and-pencil survey. Soldiers were given a complete description of the study. Those who elected to complete the survey provided their consent under a protocol approved by the institutional review board at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Measures

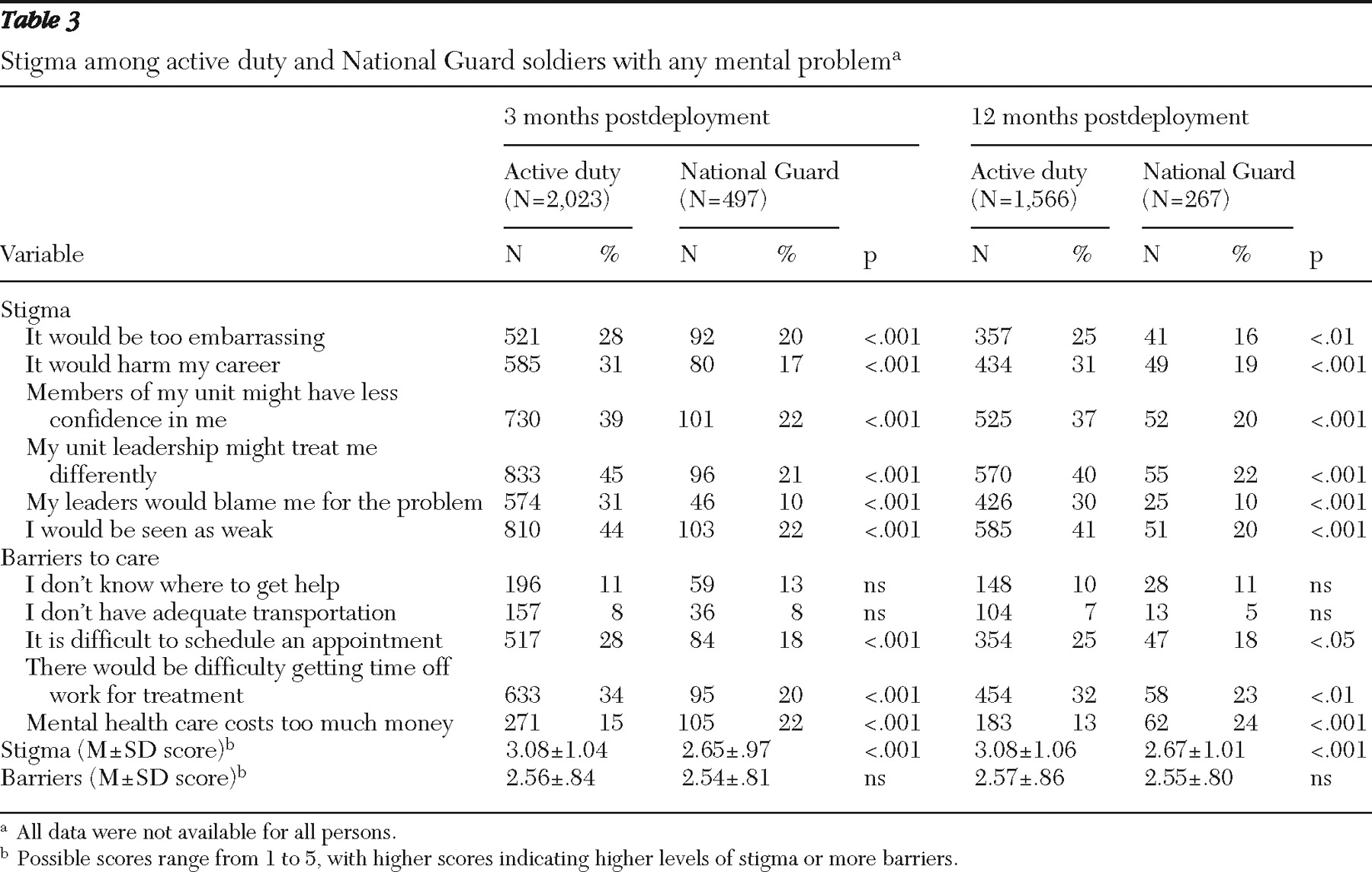

Stigma was measured with a six-item scale assessing common concerns about receiving mental health services (for example, "I would be seen as weak"). These, as well as the items on barriers to care, were originally developed by Hoge and colleagues (

1 ) and have been used in recent studies (

9,

11 ). Each item was measured on a 5-point scale (1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree). Cronbach's alpha for this scale was .95.

Organizational barriers to care were measured with the same 5-point scale and included five items (for example, "I don't know where to get help"). These items were originally developed by Hoge and colleagues (

1 ) and have been used in recent studies (

9,

11 ). Cronbach's alpha for this scale was .86.

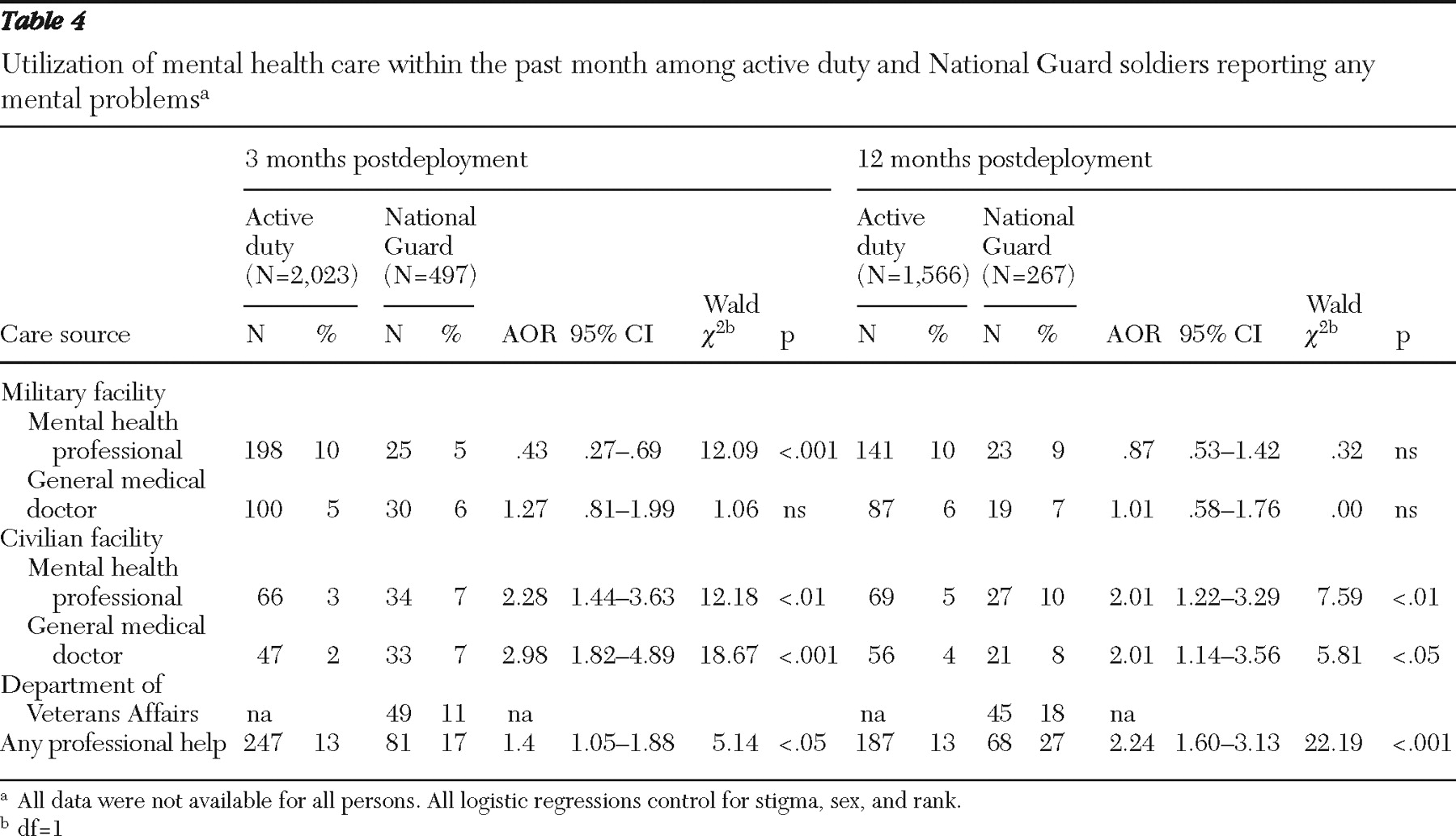

Service utilization rates were measured by asking respondents whether they had received mental health services for a stress, emotional, alcohol, or family problem from either a mental health professional at a military or civilian facility or a general medical doctor at a military or civilian facility. An additional utilization measure regarding mental health care from Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health facilities or veteran centers was included for National Guard soldiers. Soldiers who indicated that they had received any one of these services at least once in the past month were categorized as utilizing care.

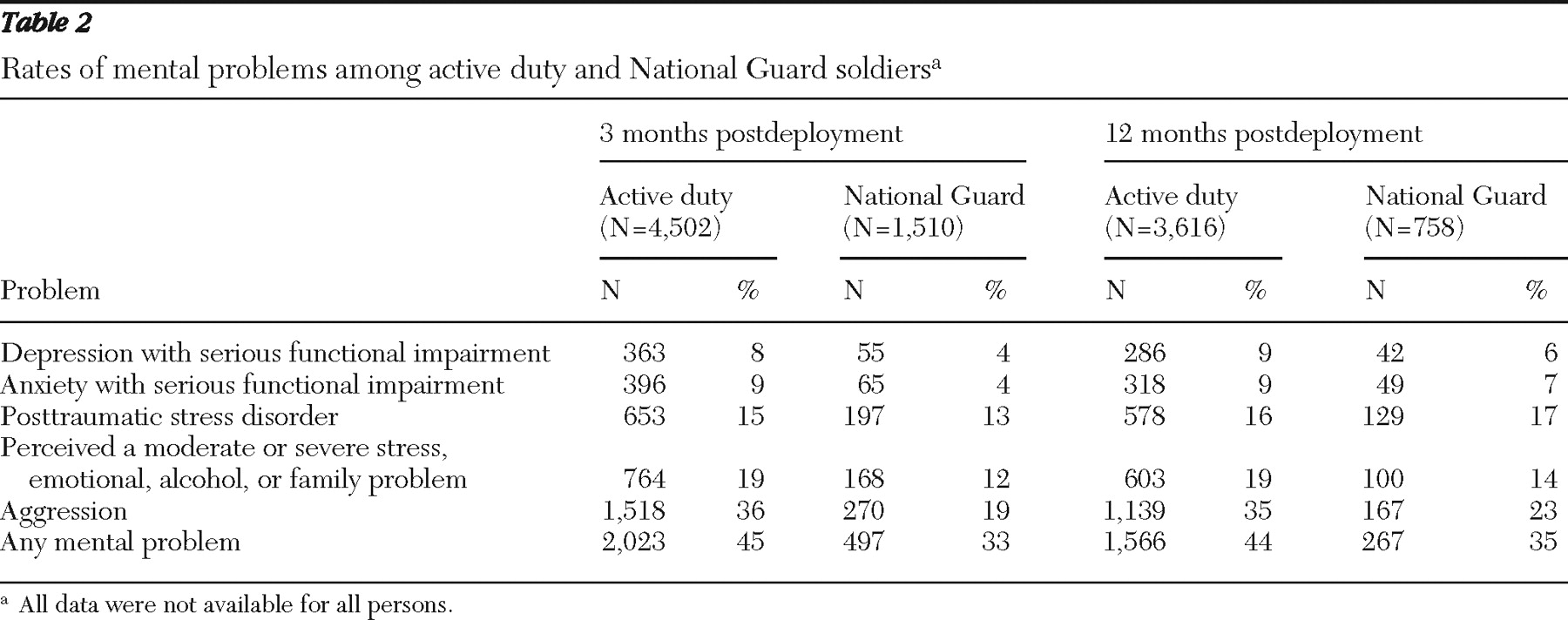

Soldiers were identified as being at risk of psychiatric problems if they had screened positive for major depressive disorder, severe anxiety symptoms, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); if they reported frequent aggressive behaviors; or if they reported any overall problems related to relationships, distress, or alcohol at the moderate or severe level (

1 ).

Depression levels were measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) (

12 ), a standard approach in recent studies of soldiers (

1,

13,

14 ). Soldiers who indicated that they had been bothered by at least five of nine depression symptoms for more than half the days in the past month and reported either "little interest or pleasure in doing things" or "feeling down, depressed, or hopeless" more than half the days in the past month were considered to screen positive for depression. Additionally, in order to screen positive, respondents needed to endorse that their depression symptoms made it very or extremely difficult to function at work or home or to get along with other people.

Severe anxiety was measured using six items from the PHQ. Respondents endorsing three of the six items for more than half the days within the past month and indicating that they feel bad about themselves—or that they are a failure or have let themselves or their family down for more than half the days in the past month—were considered to have severe anxiety symptoms. As with the depression measure, respondents also had to report that their anxiety symptoms made it very or extremely difficult to function at work or home or in getting along with other people.

PTSD was assessed with the 17-item PTSD Checklist (PCL) (

15,

16 ), a well-validated measure of the severity of symptoms related to stressful experiences that follows current

DSM-IV guidelines (

17 ). Soldiers who reported that they had been bothered moderately by at least one intrusion symptom, three avoidance symptoms, and two hyperarousal symptoms within the past month and also scored 50 or higher on the overall PCL scale screened positive for PTSD (

18 ).

Aggressive behaviors were assessed with three items previously used by Killgore and colleagues (

19 ). Respondents who reported either "getting angry with someone" or that they "kicked or smashed something" at least three times in the past month or who reported "threatening someone with violence" at least twice in the past month or "getting into a fight" at least once in the past month were considered to be at risk of mental problems.

Respondents were also asked whether they had experienced a stress, emotional, alcohol, or family problem within the past month. Those who indicated a moderate or severe problem were considered to be at risk of mental problems. This measure has been used in a similar manner in a previous study examining military mental health (

1 ).