Rapid sociocultural changes in Native American communities are reflected in the nature and extent of mental health problems in these populations (

1). Several community surveys have reported high rates of psychiatric disorders. Using structured diagnostic interviews, Kinzie and associates (

2) found that 69 percent of the adult population in an American Indian village had a definite or probable mental disorder, compared with 32 percent in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study of the general U.S. population (

3). Rates of addictive diseases and depression are especially high (

2,

4,

5). For example, lifetime prevalence rates of alcohol dependence or abuse within selected American Indian communities range from 27 to 51 percent (

2,

6).

Most epidemiological surveys in Native American populations have used problem checklists or questionnaires to measure psychopathology (

4,

5). Some have used structured diagnostic interviews to classify American Indian subjects using a modern diagnostic system (

2,

6), but sample sizes have been small and such studies have not been performed in Eskimo populations.

During his clinical work at the regional community mental health center in Nome, Alaska, one of the authors (RJG) noted a low rate of bipolar disorder (manic-depressive illness) and eating disorders among Eskimo patients attending the clinic. This observation, along with the lack of studies measuring rates among Eskimos of psychopathology according to our current diagnostic classification system, prompted the study described in this paper. We report the rates of psychiatric disorders among Eskimos attending a community mental health center in Western Alaska and offer possible explanations for these findings.

Methods

The Eskimos in the Bering Straits region of Alaska are members of four distinct ethnic groups: Inuit, Inupiat, Yupik, and Siberian Yupik. Although the people retain much of their traditional values and life style, almost all are literate in English.

Any person in the region is eligible to receive services at the community mental health center (CMHC) in Nome. Many patients are referred by their local medical provider.

The study population includes all Eskimo patients evaluated by the staff psychiatrist (RG) at the CMHC between October 1990 and April 1993. Charts were reviewed retrospectively, and data on demographic characteristics, DSM-III-R diagnoses, and history of suicide attempts were collected. Between-group differences were analyzed using two-tailed chi square tests with Yates correction.

Results

Over the two years of the study, 343 Eskimo patients—88 children and adolescents between the ages of six and 17 years and 255 adults age 18 and older—were evaluated. Among the children and adolescents there was a slight preponderance of females (N=49). The mean age of the children and adolescents was 14±2.3 years. The mean age of the adult patients was 37±15 years.

Most youths had problems with substance use disorders (N=49), but females most frequently used alcohol, and males surprisingly were more likely to have problems with inhalants. Eating disorders were infrequent (N=3).

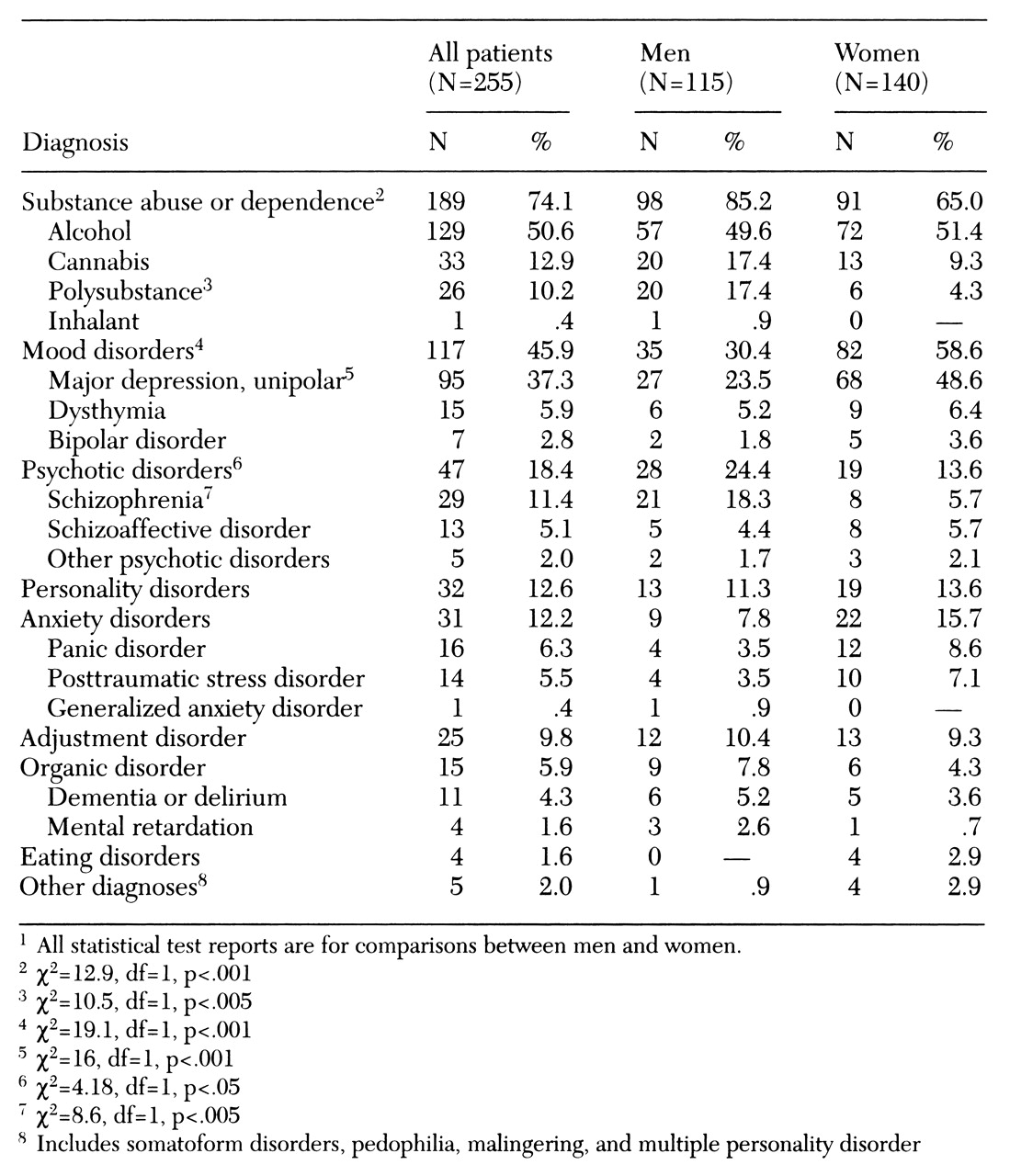

Table 1 outlines the distribution of diagnoses among the adult patients. Substance use disorders were prevalent, especially among men. Whereas inhalant use was much less frequent among adults compared with children, alcohol and cannabis use were much more frequent.

Most surprising was the low frequency of bipolar disorder (manic-depressive illness) and eating disorders. One would expect that approximately equal numbers of patients would have bipolar disorder as would have schizophrenia in a mental health clinic (

7), but less than 3 percent of these Eskimo patients received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Sixty-six percent of the children and 67 percent of the adults reported a previous suicide attempt. An interesting finding was that the two age groups differed in the gender distribution of the suicide attempters (χ2= 11.6, df=1, p<.001), with females reporting higher rates among youths and adult men and women reporting approximately equal rates. This difference suggests that suicide may have different etiologies in different age groups.

Discussion and conclusions

Perhaps our most striking finding is the high prevalence of substance use disorders in both children and adults attending the mental health clinic. The substances of choice appeared to be alcohol, cannabis, and inhalants, and preference varied by age and by gender. Although striking, the finding was not unexpected, as high rates of substance use have been noted in surveys fairly consistently across Native American ethnic groups (

8). Reasons for these consistent findings are unknown, but may include biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors (

2,

4).

Of concern was a 67 percent rate of reported suicide attempts. This rate compares with rates of 4 to 25 percent reported in other mental health clinics (

7). Suicide rates vary widely among Native American tribes and subgroups (

8). Acculturation and high rates of alcoholism have been the most common explanations given for Native American suicide (

9), but a more recent study in this Eskimo population suggested that early parental loss and limited grieving mechanisms are important factors (

10).

This study supported our prediction of low rates of eating disorders and bipolar disorder. In the general U.S. population, an outpatient mental health clinic might expect that approximately 8 percent of its adult patients would have bipolar disorder (

7). In contrast, we found a rate of 3 percent in our clinic. To our knowledge, this is the first time that a low rate of bipolar disorder has been reported in a Native American population.

A low rate of eating disorders is easily explained by culturally based differences in attitudes towards body weight and appearance. It is more difficult to explain the low rate of bipolar disorder. One possibility is sampling bias—that is, the expected number of persons with bipolar disorder lived in the community, but they did not come to our clinic. We believe this explanation is unlikely given the disabling nature of the illness and the lack of alternative mental health resources in the region.

Another possible explanation is that our subgroup, or Native Americans as a whole, have low genetic loading for bipolar disorder or a different phenotypic expression of the illness. For example, high rates of cannabis use may have led to a psychotic diathesis of a bipolar predisposition, thereby causing a predominantly psychotic manifestation of bipolar illness. In support of this explanation, we found that cannabis use was highly correlated with assignment of a psychotic disorder (χ2=23.6, df=1, p<.001). In addition, our clinical observation was that many of the patients that were diagnosed with schizophrenia appeared to respond to mood stabilizers.

The limitations of the study include its use of retrospective analysis and assignment of diagnoses based on the clinical evaluations of a single psychiatrist. This study highlights the need for similar studies in other Native American clinic populations, as well as systematic community surveys employing structured diagnostic interviews and a modern diagnostic classification system.