There is considerable public and professional concern about access to mental health services for recently returned veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. A survey of three groups of veterans (N=3,671) who returned from Afghanistan and Iraq found that 11%–17% met screening criteria for a mental disorder but 60%–77% of those who met screening criteria expressed no interest in treatment (

1,

2). Moreover, although 78%–86% of those who screened positive for depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or generalized anxiety disorder acknowledged these emotional difficulties, only 38%–45% indicated an interest in receiving help and only 13%–21% had actually received help from a mental health professional in the year before assessment. High rates of mental disorders were also recorded among Vietnam-era veterans and military personnel in the 1990s, and the burden associated with mental illnesses in these populations was found to be significant (

3–

5).

Unmet needs for mental health services are not unique to veterans. Using data from the National Comorbidity Survey, Kessler and colleagues (

6,

7) estimated that ten million persons in the United States meet criteria for a serious mental illness in any given year but only 50%–60% receive treatment. Fifty-five percent of those who did not receive services cited a lack of perceived need, and the rest wanted to solve the problem on their own (72%), thought the problem would get better by itself (61%), faced financial barriers (46%), were unsure about where to go for help (41%), or thought that help would not do any good (38%). In this national sample, younger people (aged 18–34) were the least likely to seek care, a finding consistent with data from the military showing limited help-seeking behavior among the younger veterans (

8).

In addition to this evidence of widespread untreated mental illness, the attrition of patients who have entered psychiatric treatment has also long been a concern. Studies from the 1950s and 1960s reported that about 50% of patients dropped out of psychiatric treatment by the third session, with approximately 35% of clients ending therapy after a single session (

9–

11). More recent studies show that from 20% to 57% of patients drop out after the first session of mental health treatment (

12–

16). It has also been reported that more than 65% of clients end psychotherapy before the tenth session, and most have been found to attend fewer than six sessions (

13,

17).

Premature dropout is a concern for several reasons. Research has shown that successful symptom reduction in short-term, evidence-based psychotherapy usually requires a minimum of nine to 15 sessions for even half of the clients to be considered recovered (

18,

19). Thus the majority of clients who enter treatment do not seem to receive the minimum number of sessions needed to achieve clinical benefits. Premature dropout may also waste limited mental health resources.

This study used national administrative data from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to examine the one-year duration of participation in mental health treatment among veterans with a new diagnosis of PTSD and who served in Iraq as part of Operation Iraq Freedom (OIF) or who served in Afghanistan as part of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). These veterans were compared with veterans newly diagnosed as having PTSD from other service eras: Korean, Vietnam, post-Vietnam (1975–1992), or Persian Gulf (1992 to the present), excluding veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan as part of OIF or OEF.

Methods

Source of data and sample

The sample was based on national VA administrative data. Veterans were included if they were treated in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) from fiscal year (FY) 2004 to FY 2007 and received a primary or secondary diagnosis of PTSD on at least one outpatient encounter or inpatient discharge and who had not had any service encounters associated with a PTSD diagnosis for the previous three years (since FY 2001) (N=204,184). One-year treatment discontinuation was defined if the last PTSD-related encounter occurred less than 360 days after the initiation of the service episode for treatment of PTSD. Data on service use, sociodemographic and diagnostic characteristics, and service era were derived from national administrative databases, including the outpatient encounter file, which documents all outpatient service use, and the patient treatment file, which includes discharge abstracts of all VHA inpatient treatment. Data on service in Iraq or Afghanistan were obtained from files provided to the VA by the Department of Defense. The records of these patients were then merged to create the database examined for this study. Veterans were classified into six mutually exclusive service era categories: Korean, Vietnam, post-Vietnam, Persian Gulf exclusive of service in Iraq or Afghanistan (OIF or OEF), and OIF-OEF. A waiver of informed consent was obtained from the VA Connecticut and Yale institutional review boards.

Measures

Measures reflected patient characteristics, including age, gender, race-ethnicity, receipt of VA disability compensation, annual income, comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, and outpatient and inpatient mental health service utilization.

ICD-9 codes were used to identify the following nonmutually exclusive comorbid diagnoses during the year after the first PTSD visit: schizophrenia, alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and dysthymia. In addition, we identified the number of outpatient mental health visits each patient had during the year after the first diagnosis of PTSD and determined whether the patient was hospitalized on an inpatient psychiatric unit that year. Veterans' residence in urban or rural areas was also included because it may also have affected access to outpatient health services. Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) classification codes developed in 1998 at the University of Washington (

http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-about.php) and national zip code data from the VA encounter files were used to identify veterans living in settings ranging from large urban locations to isolated rural ones. The zip code of residence on the first encounter record of the FY was matched with zip codes from the RUCA categories, which classified each veteran's residence as urban, large rural city, small rural community, or isolated rural setting.

In addition to the first date of a diagnosis of PTSD, we also identified the last visit that included a diagnosis of PTSD through December 2007 and subtracted that date from the date of the first PTSD visit. Retention in treatment was thus measured by the number of days from the initial PTSD diagnosis through December 2007. We also examined the number of visits specifically for the diagnosis of PTSD and the total number of specialty mental health visits regardless of diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluatebivariate associations betweenservice era and retention in mental health treatment, and generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to assess treatment intensity (as measured by number of visits). Survival analysis (proportional hazards regression) including all covariates was used to estimate the likelihood of dropping out of treatment during the first year after receiving a diagnosis of PTSD among OIF-OEF veterans and veterans of other war eras (Vietnam-era veterans were the reference group). SAS, version 9.1, PROC PHREG was used to perform the survival analysis.

Next, because we observed events within a defined unit of time, Poisson regressionwas used to assess the association betweenwar era and the number of visits during the first year of treatment. The analyses used PROC GENMOD of SAS and adjusted for all other covariates and duration of participation. Because of the large number of participants in the study, we set the alpha significance level to .001.

Results

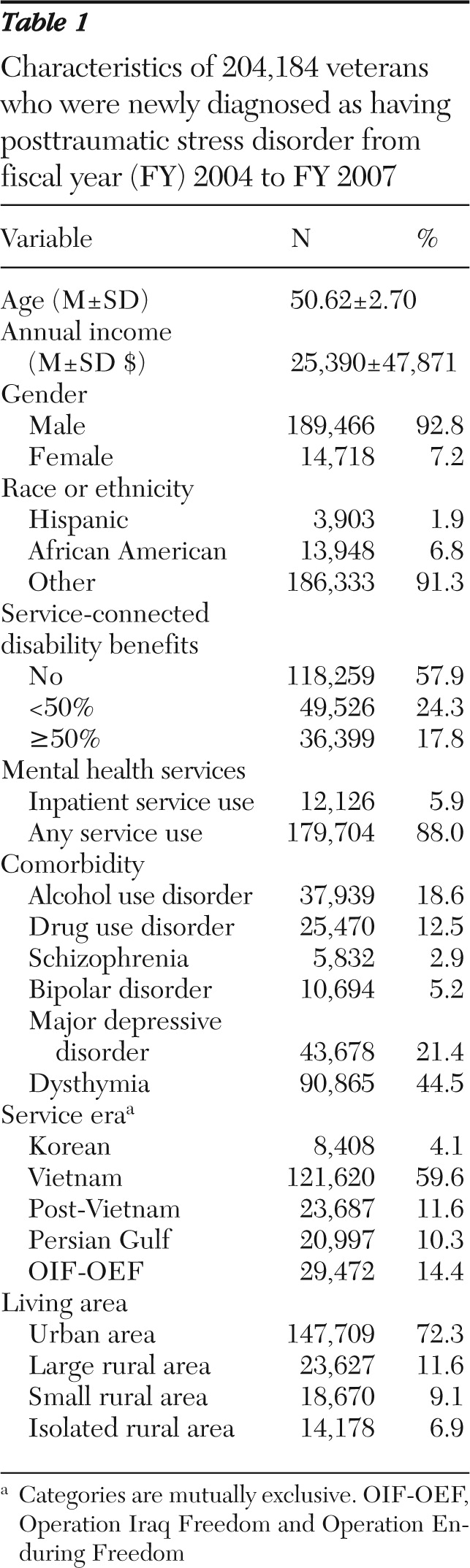

The sample included 204,184 veterans; 92.8% were males. The mean age was 50.62 years, 6.8% were African American, and 1.9% were Hispanic (

Table 1). Altogether 42.1% received service-connected disability benefits from the VA, and the sample had an average annual income of $25,390. About 6% had an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization during the year that they originally received a PTSD diagnosis, and 88.0% received specialty mental health services. The most frequent comorbid diagnoses among veterans diagnosed as having PTSD were dysthymia (44.5%), major depressive disorder (21.4%), and alcohol use disorder (18.6%). The majority of veterans treated for PTSD during the observed period served during the Vietnam era (59.6%), followed by those who served in OIF-OEF (14.4%).

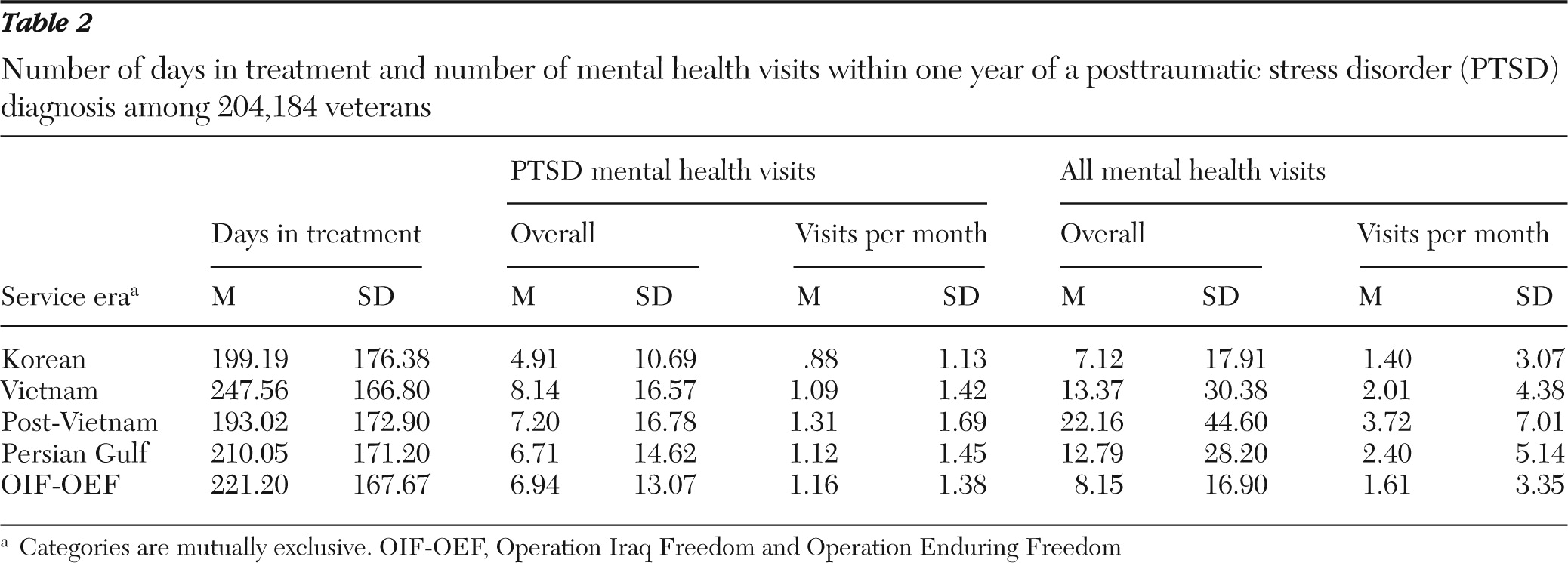

GLMs compared the number of days veterans were retained in treatment during the first year after treatment entry, the number of mental health treatment visits attended, and the average number of visits per month.

Table 2 provides details on the adjusted means and standard deviations of visit counts for veterans of each service era. Veterans of the Vietnam War were retained in PTSD treatment for an average of 247.56 days, whereas OIF-OEF veterans who were treated for PTSD were retained for 221.20 days. The adjusted mean number of outpatient visits for the treatment of PTSD among Vietnam-era veterans was 8.14, and the average number of visits for any specialty mental health services for this group was 13.37±30.38. These figures were somewhat lower for OIF-OEF veterans (6.94±13.07 and 8.15±16.90, respectively). Overall, veterans from all eras attended an average of one PTSD specialty mental health visit per month during the first year of treatment.

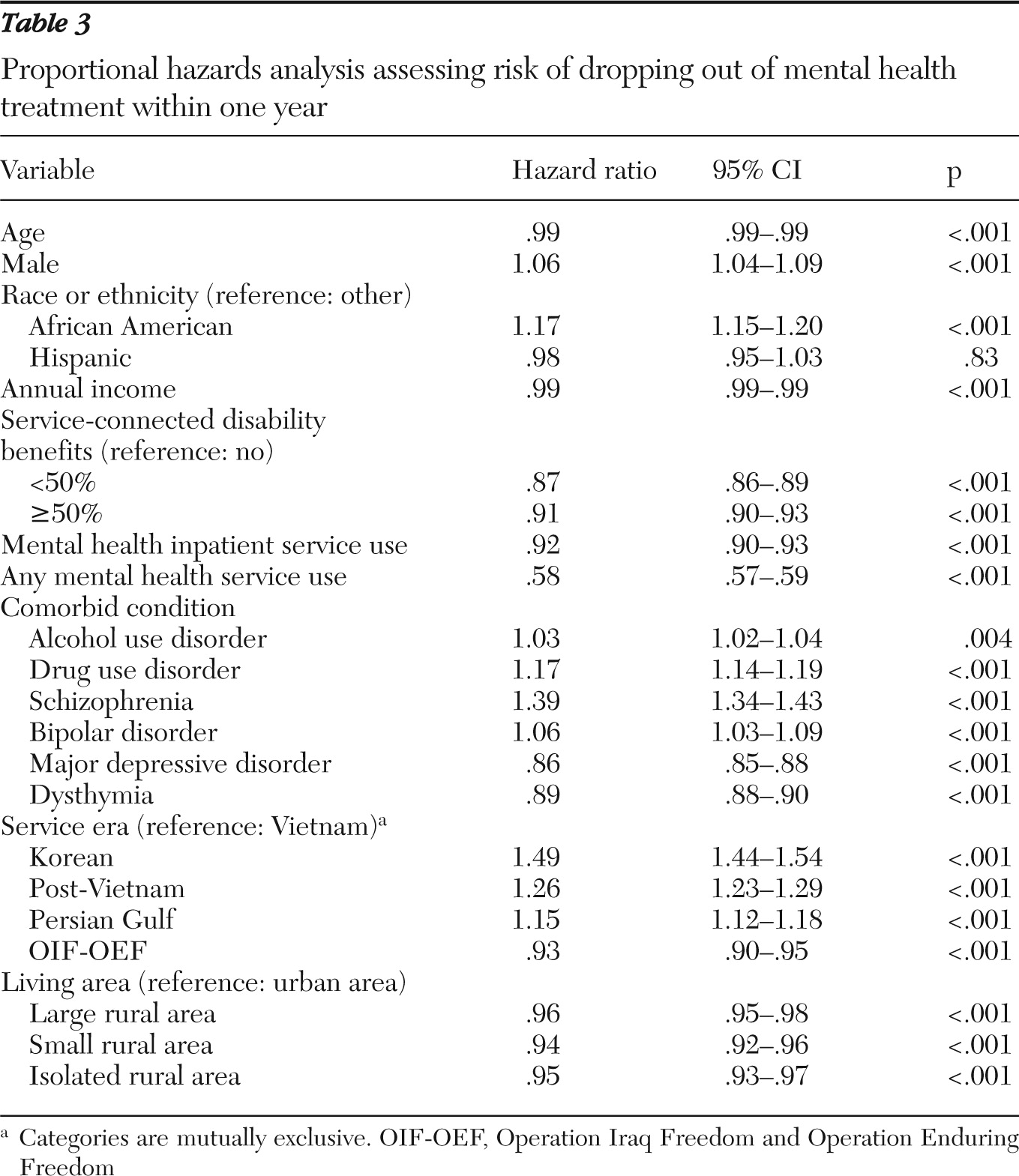

Bivariate data suggested that OIF-OEF veterans drop out of treatment at a moderately greater rate than their Vietnam-era counterparts. Altogether 37.6% (N=11,081) of the OIF-OEF veterans and 46.0% (N=55,896) of Vietnam-era veterans remained in treatment for more than one year. However, proportional hazards models adjusting for demographic and comorbid diagnoses showed that compared with the Vietnam-era veterans, OIF-OEF veterans were 7% less likely (hazard ratio=.93) to discontinue their psychiatric treatment for PTSD within the first year after the initial diagnosis (

Table 3). Overall, veterans were less likely to drop out of treatment within the first year if they had higher income, were older, received specialty mental health services (compared with primary care medical services), had an inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, received service-connected disability benefits from the VA, or were diagnosed as having mood-related disorders (either major depressive disorder or dysthymia) (

Table 3). Veterans residing in nonurban communities were less likely than those residing in urban areas to discontinue their PTSD treatment within the first year after their initial diagnosis.

Increased risk of discontinuing treatment within the first year was significantly associated with being male, being African American, and having a comorbid diagnosis of an alcohol or drug use disorder, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder. Compared with Vietnam-era veterans, veterans who served during the Korean era, the post-Vietnam era, and the Persian Gulf era (excluding OIF-OEF veterans) were all more likely to drop out of treatment during the first year after their initial PTSD diagnosis (

Table 3).

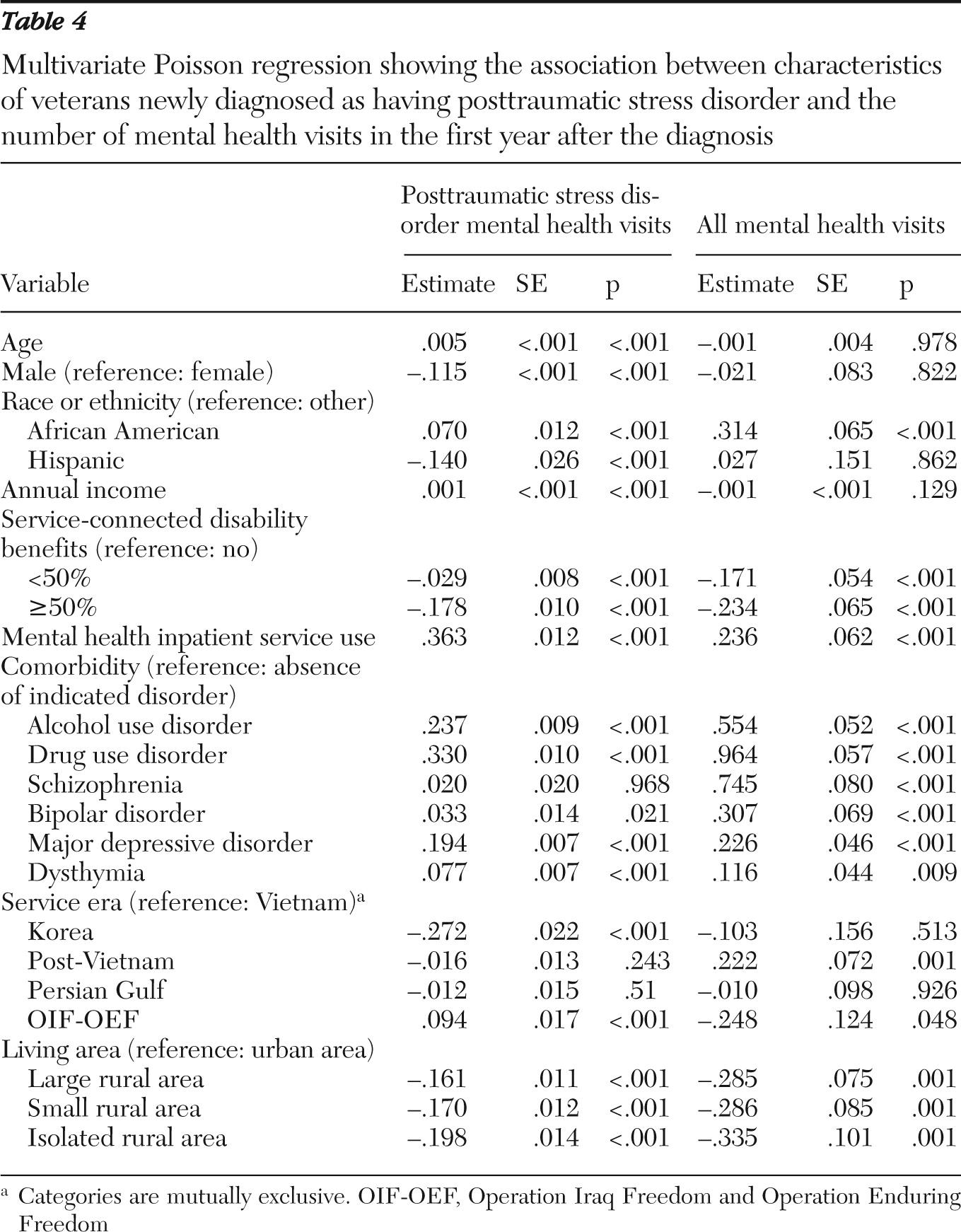

Poisson multivariate analysis indicated that compared with Vietnam-era veterans, OIF-OEF veterans had significantly more PTSD treatment visits (

Table 4). Also, veterans had significantly more visits if they were older, had higher incomes, were African American, received inpatient mental health services, or had a comorbid diagnosis of alcohol or drug use disorder or a mood-related disorder. Lower numbers of PTSD-related visits were associated with being male, being Hispanic, receiving service-connected disability benefits, serving during the era of the Korean War, or living in rural areas.

Finally, we examined correlates of the number of all specialty VA mental health visits. Poisson regression suggested that veterans received more services if they were African American, received inpatient services, or had a comorbid diagnosis of an alcohol or drug use disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder (

Table 4). Compared with Vietnam veterans, post-Vietnam veterans received a significantly larger number of mental health visits. Lower numbers of mental health visits were associated with receiving service-connected disability benefits from the VA and living in rural areas. Veterans who served during OIF-OEF era were not significantly different from their Vietnam-era counterparts.

Discussion

As many veterans return home from a difficult tour in a war zone, there is great concern that appropriate services be provided to facilitate their readjustment and address the physical and emotional toll of their warzone service. It has recently been documented that from 1997 to 2005 there was a steady and constant growth in the number of veterans using specialty mental health services within the VA, which was associated with an annual reduction of 37% in the number of mental health visits per veteran (

20). However, there have been substantial increases in the expenditures on mental health care through FY 2008 (

21) and in the average number of mental health visits per veteran with PTSD from FY 2006 to FY 2010 (unpublished data, New England Mental Illness, Research, Education, and Clinical Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, 2010). This study was designed in response to recent growing concerns about the retention of OIF-OEF veterans in mental health treatment.

Our data indicated that when examined independently of other factors, OIF-OEF veterans were treated for a shorter period and received fewer mental health services when compared with veterans of the Vietnam era. However, when Poisson regression was used to account for events within a defined period of time (one year after the initial diagnosis) and to adjust for potential confounds, OIF-OEF veterans were more likely than Vietnam-era veterans to be retained in treatment. Moreover, Poisson multivariate regression indicated that OIF-OEF veterans received a slightly but significantly larger dosage of specialty PTSD mental health services (number of visits adjusted for time) than their Vietnam veteran counterparts. Furthermore, no significant difference was found between OIF-OEF and Vietnam veterans in the total number of mental health specialty visits. The intensity of mental health visits were primarily associated with illness severity measured by comorbid diagnosis. It is possible that providers may have given PTSD diagnoses more readily to newly returning veterans than to older veterans, resulting in a significantly greater number of mental health visits associated with PTSD diagnosis among OIF-OEF veterans than among veterans of other eras.

Moreover, although one part of the sample (OIF-OEF veterans) is at the beginning of the course of the disorder, a new PTSD diagnosis among Vietnam-era veterans would have occurred after a considerable passage of time since the their return from overseas. In this respect, these veterans may have either suffered from this disorder for a long period and not sought any mental health services or experienced a late onset or reemergence of stress-related symptomatology (

22).

Our study suggests that, on average, OIF and OEF veterans attended only eight mental health visits during the year after their initial PTSD diagnosis, and thus they were not likely to have received sufficient sessions of short-term evidence-based psychotherapy to obtain a significant reduction in symptoms in that year. Data on how many received such treatment over longer periods or on the reasons why only eight visits were received, on average, during the first year of treatment are not available.

This study also provided an opportunity to examine the patterns of mental health service use in terms of both continuity (time) and dosage (number of mental health visits) during the first year after the beginning of a new episode of treatment. This can be viewed in the perspective offered by Andersen's model (

23,

24) of service utilization, which suggests that service utilization is influenced by characteristics of both individuals and health care systems. Although there is a concern that OIF-OEF veterans drop out earlier and receive fewer visits, this appears to be a function of age and comorbid conditions and not the particular era in which they served. As a system, the VA offers relatively similar services to veterans of all conflict eras. However, although veterans who received service-connected disability benefits from the VA (which provide free access to services along with the monthly disability payment) had a lower risk of discontinuing mental health services within the first year after the initial PTSD diagnosis (

Table 2), they also had a significantly lower number of both specialty PTSD mental health service visits or of any mental health specialty visits compared with veterans who did not receive any service-connected disability payments. These findings suggest that veterans who have no financial assistance from the VA and seek medical care within the VA health care system tend to receive more mental health services within a shorter period of time, which suggests that needs and not financial incentives drive service utilization.

Similarly, living in a rural area was associated with a significantly lower risk of terminating mental health treatment within the first year after the initial PTSD diagnosis but also with a significantly lower dosage of both PTSD mental health service and any mental health services. These findings suggest that geographical barriers may restrict the intensity of services but do not interfere with treatment retention.

This study has several limitations that restrict our ability to draw definitive conclusions about the nature of service use among VA patients with PTSD, especially among those who served in Iraq or Afghanistan. First, the study used administrative data on diagnosis, the validity of which has not been determined, and further data on severity of illness were not available. Second, we have no information on non-VA mental health service use by these veterans, which may have resulted in an underestimation of service utilization, especially among veterans who did not receive service-connected disability benefits. However, there is evidence from the Vietnam generation that veterans with PTSD are far more likely to use VA services than non-VA services and that the delivery of services for PTSD in populations supported by private insurance is far more uncommon than is the delivery of such services in the VA (

25).