Ideal continuity of care can be defined as seeing the same physician for all office visits. With better care continuity, interactions between patients and providers improve, trust is established, and patients receive appropriate and timely preventive care and chronic disease management. This idealized version of care continuity is rarely realized, particularly for patients with multiple chronic conditions. In 2000–2002, the average Medicare fee-for-service beneficiary saw two primary care physicians and five specialists (

1). Moreover, beneficiaries with diabetes saw eight physicians, and the number of physicians seen increased with the number of chronic conditions (

1).

To improve care coordination and management for patients with chronic conditions, the patient-centered medical home has been proposed to provide a single, consistent point of care that provides continuity of clinical information and treatment decisions for the patient. A medical home that leverages information technology to promote longitudinal relationships, care coordination, and comprehensiveness holds promise for improving care of patients. However, continuity of care and medical homes relate not just to appropriate and timely provision of health services with a single point of care but also to appropriate and timely prescribing of new medications and dosing changes for existing medications. Thus we define optimal continuity of medication management in this study as having a single prescriber who is responsible for antipsychotic medication management.

Patients with multiple providers may have suboptimal refill patterns (filling prescriptions too infrequently or even too frequently) because multiple providers who are comanaging a patient's medication may be unaware of each other's prescribing. As a consequence, the patient may be confused by conflicting information from different providers. In addition, adverse events caused by overlapping treatments could induce underadherence, and therapeutic duplication could induce excess filling of antipsychotic medications. Continuity in medication management may be particularly important for people with schizophrenia because nonadherence to antipsychotic medications has been associated with symptom relapse (

2), greater treatment nonresponsiveness (

3), more frequent emergency department encounters (

4), and greater risk of psychiatric hospitalization (

5,

6). Nonadherence may refer both to underutilization of antipsychotic medication and to overutilization, which has been shown to result in higher hospitalization rates and medical expenditures (

7).

In this study, we examined the relationship between the number of antipsychotic prescribers, medication switching, and refill behavior among Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. We focused on the continuity of medication management in this group because medication adherence is a significant problem for patients with schizophrenia and because the highest prevalence of schizophrenia in the United States is in the Medicaid population (2%) (

8). We examined medication adherence by using a four-level outcome (nonadherence, partial adherence, full adherence, or excess filling). These categories of adherence have previously been used to examine the effect of nonadherence on clinical outcomes (

7). The term “excess filling,” which is used throughout this article, refers to patients who may fill antipsychotic prescriptions earlier than recommended, leading to an oversupply of antipsychotic medication. It may also refer to patients' using multiple antipsychotics simultaneously, which is not recommended in antipsychotic treatment guidelines. Although it is common practice to dichotomize adherence using algorithms from administrative claims data, such as the medication possession ratio (MPR) with a cutpoint of 80%, this dichotomization masks potential excess supply that this four-level categorization can clarify. This four-level grouping partitioned nonadherence into two clinically meaningful subgroups: nonfillers who received little clinical benefit from infrequent medication use and intermittent fillers who were likely to experience moderate clinical benefit. Results of this study can inform ongoing developments related to medical homes for patients with schizophrenia and future interventions targeting care coordination and continuity of care.

Methods

Sample

The sample for this study was drawn from a population of patients with schizophrenia who were continuously enrolled in North Carolina Medicaid from 2001 to 2003; we used data from the Medicaid Analytic Extract. Using a previously validated algorithm (

9), we identified 19,187 patients with schizophrenia who had at least one inpatient or two outpatient diagnoses with

ICD-9-CM code 295.xx (

9). We excluded 5,938 patients who were not continuously enrolled with full Medicaid benefits. To ensure complete data for the sample, we applied additional exclusions to 475 patients who also had private insurance coverage and 959 patients who were enrolled in Medicare and lacked full Medicaid benefits. To assess the effect of continuity of care of antipsychotic use, patients were excluded if they did not have any antipsychotic drug claims in 2003 (N=1,372). Finally, patients with missing information pertaining to their prescriber information and covariates (N=2,575) were excluded from the analytic sample, for a final analytic sample of 7,868 beneficiaries.

The institutional review board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill reviewed and approved this study.

Outcomes

Adherence was the primary outcome and was measured by MPRs, based on 2003 antipsychotic medication refill data contained in North Carolina Medicaid claims data. MPR directly measures refill behavior and indirectly represents medication taking, and it correlates with disease control. MPR was chosen as the adherence measure in this study because it is the most commonly used adherence measure, correlates more highly than other measures with hospitalization episodes (

10), and has been recommended as an appropriate measure for assessing adherence when using administrative claims data (

11). MPR was calculated as total days' supply of antipsychotic medications dispensed per beneficiary in 2003 divided by total number of days in 2003 (365). Consistent with methods of Gilmer and colleagues (

7), we categorized continuous refill patterns into four groups: nonadherent (MPR <.5), partially adherent (.5≤ MPR <.8), fully adherent (.8≤ MPR ≤1.1), and excess filler (MPR >1.1).

We also examined the role of multiple prescribers in antipsychotic medication switching behavior. Antipsychotic switching was defined as the initiation of a second antipsychotic medication within 30 days of discontinuing an initial antipsychotic treatment, which could occur one or more times during the year.

Explanatory variables

The explanatory variable of interest was the number of unique prescribers who provided schizophrenia medication for each patient in our sample. Four distinct groups were created on the basis of the number of unique physicians who prescribed antipsychotic medication to each patient in 2002: one prescriber, two prescribers, three prescribers, or four or more prescribers.

We controlled for several covariates in the analyses. Demographic variables included age, measured as a continuous variable, gender, and race (white, African American, or other). Scores on the Quan and colleagues (

12) version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index were calculated from 2002 outpatient and inpatient claims to control for the effect of baseline comorbid health conditions on prescribing and adherence. In the models predicting refill behavior, we also controlled for whether a patient switched antipsychotic medication in 2003 to account for the possibility that switching would induce nonadherence or too-frequent filling because antipsychotic switching has been associated with increased risk of a schizophrenia-related hospital admission (

6). Medication switching could be positively associated with medication adherence if it results in excess unused medication. Alternatively, it could be negatively associated with adherence if it indicates suboptimal therapeutic matching to a patient's needs or patient inertia about filling prescriptions or taking medication in the face of conflicting information from different providers.

Analysis

In unadjusted analyses, we used t tests and chi square tests to examine differences in age, gender, race, Charlson score, and medication switching between patients in the four prescriber groups (one prescriber, two prescribers, three prescribers or four or more prescribers). The proportions of patients who switched antipsychotic medications were compared across the four prescriber groups via chi square tests. The proportions of patients who were nonadherent, partially adherent, fully adherent, or excess fillers were compared across the four prescriber groups via chi square tests. The probability of switching antipsychotic medication in 2003 was estimated with logistic regression, and the level of adherence outcome was estimated via ordered logistic regression. In both regressions, covariates were entered simultaneously and included the number of prescribers, age, gender, race, and Charlson comorbidity score. Medication switching was also controlled in the ordered logistic regression.

Results from the ordered logistic regression illustrate the association between a given covariate and outcome ordering (for example, patients with four or more prescribers were more likely than patients with one prescriber to be classified as excess fillers) but do not indicate level-specific effects (for example, the impact of having four or more prescribers on the probability of being an excess filler). To generate level-specific impacts of the number of prescribers, we predicted probabilities of adherence among patients according to number of prescribers for each of the four adherence outcomes. Based on an approach illustrated by Gottholmseder and colleagues (

13), these predicted probabilities illustrate the relative risk of being nonadherent, partially adherent, fully adherent, or an excess filler in 2003, given the number of prescribers in 2002, with all other covariates held constant at their mean values.

Results

Unadjusted differences in patient characteristics and refill behavior

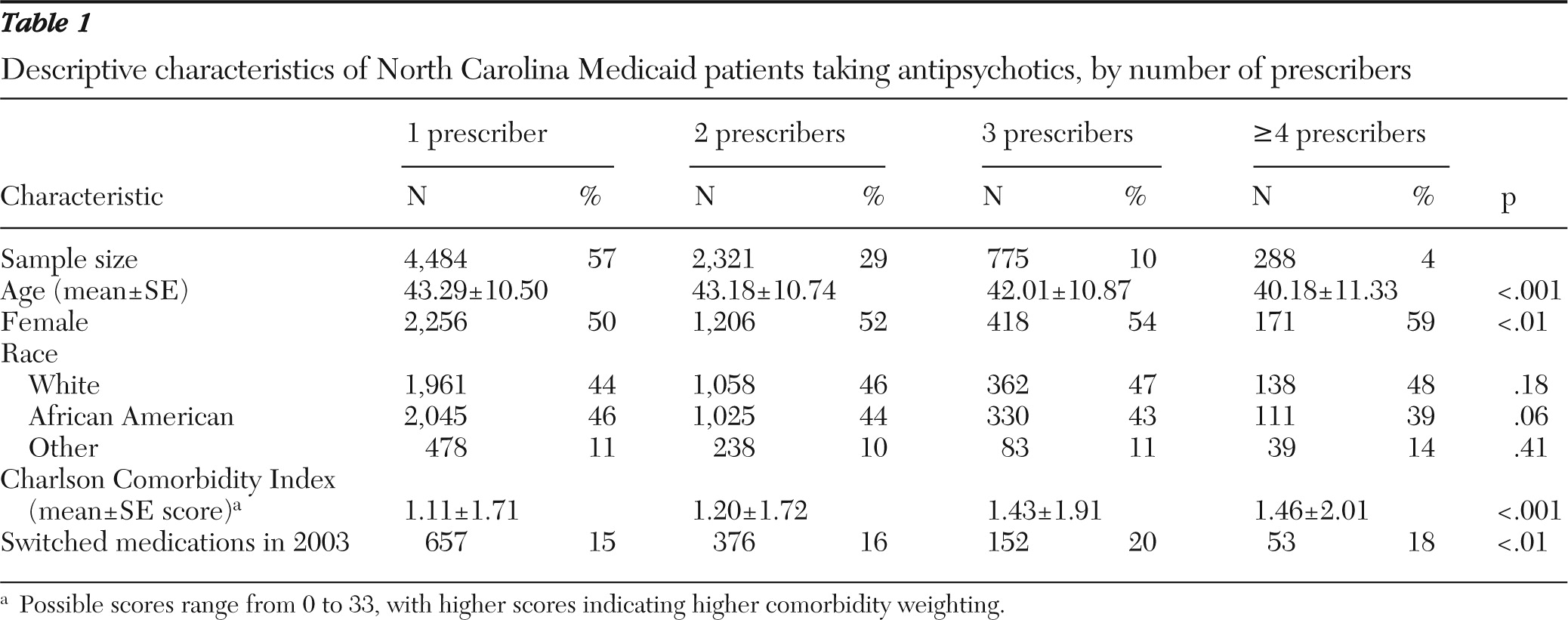

Of the 7,868 patients in the final sample, 57% had one prescriber of antipsychotic medication, 29% had two prescribers, 10% had three prescribers, and 4% had four or more prescribers in 2002 (

Table 1). On the basis of bivariate statistics, patients with more prescribers were younger (p<.001) and more likely to be female (p<.01) and to have higher Charlson comorbidity scores (p<.001) than patients with fewer prescribers. The proportion of patients who switched antipsychotics also varied significantly by the number of prescribers (p<.01), with generally higher switch rates among patients with three or more providers than among patients with one or two providers.

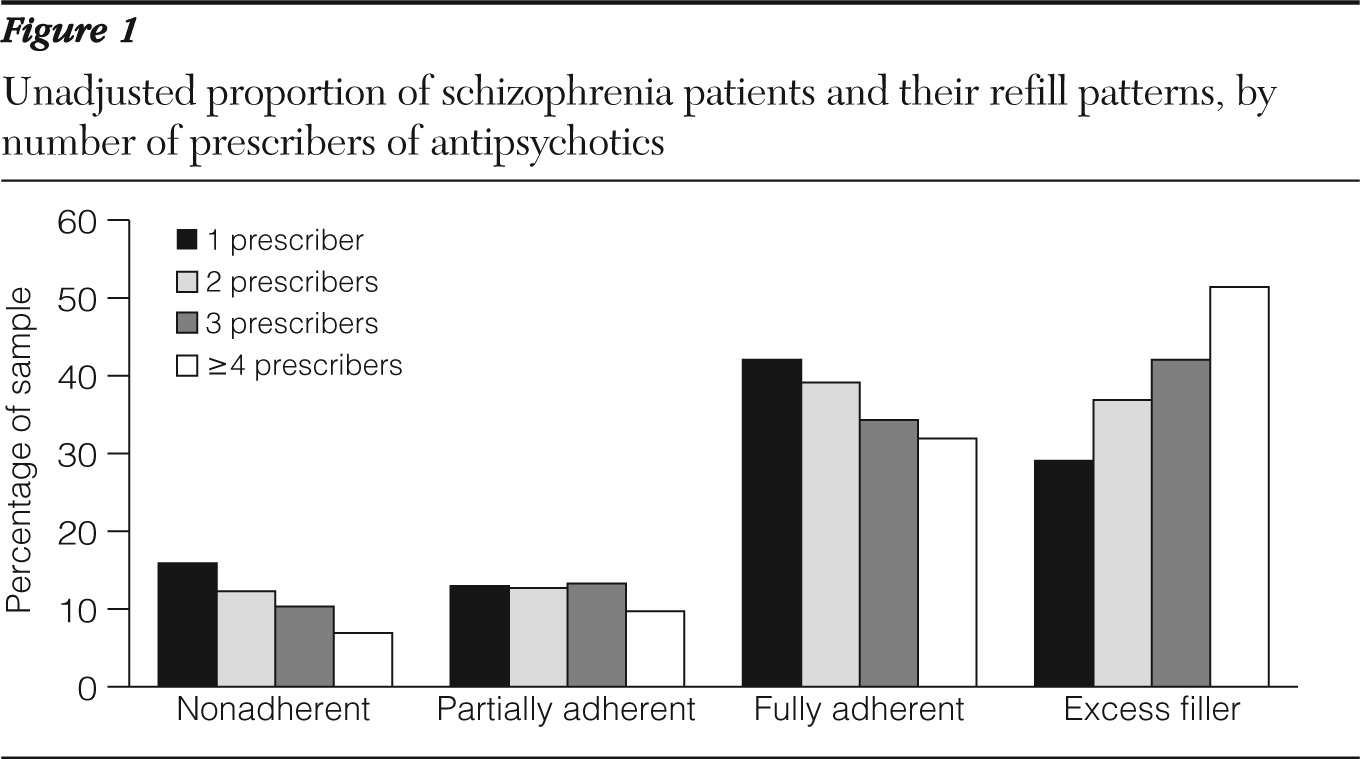

Unadjusted comparisons of adherence differences (

Figure 1) between prescriber groups indicated that patients were more likely to be nonadherent (MPR <.5) or fully adherent (.8 ≤ MPR ≤ 1.1) if they had fewer prescribers (p<.001 for both). Patients were more likely to be classified as excess fillers as the number of prescribers increased (p<.001). Fifty-one percent of patients with four or more prescribers were excess fillers, compared with 29% of patients with one prescriber.

Adjusted differences in medication switching and refill behavior

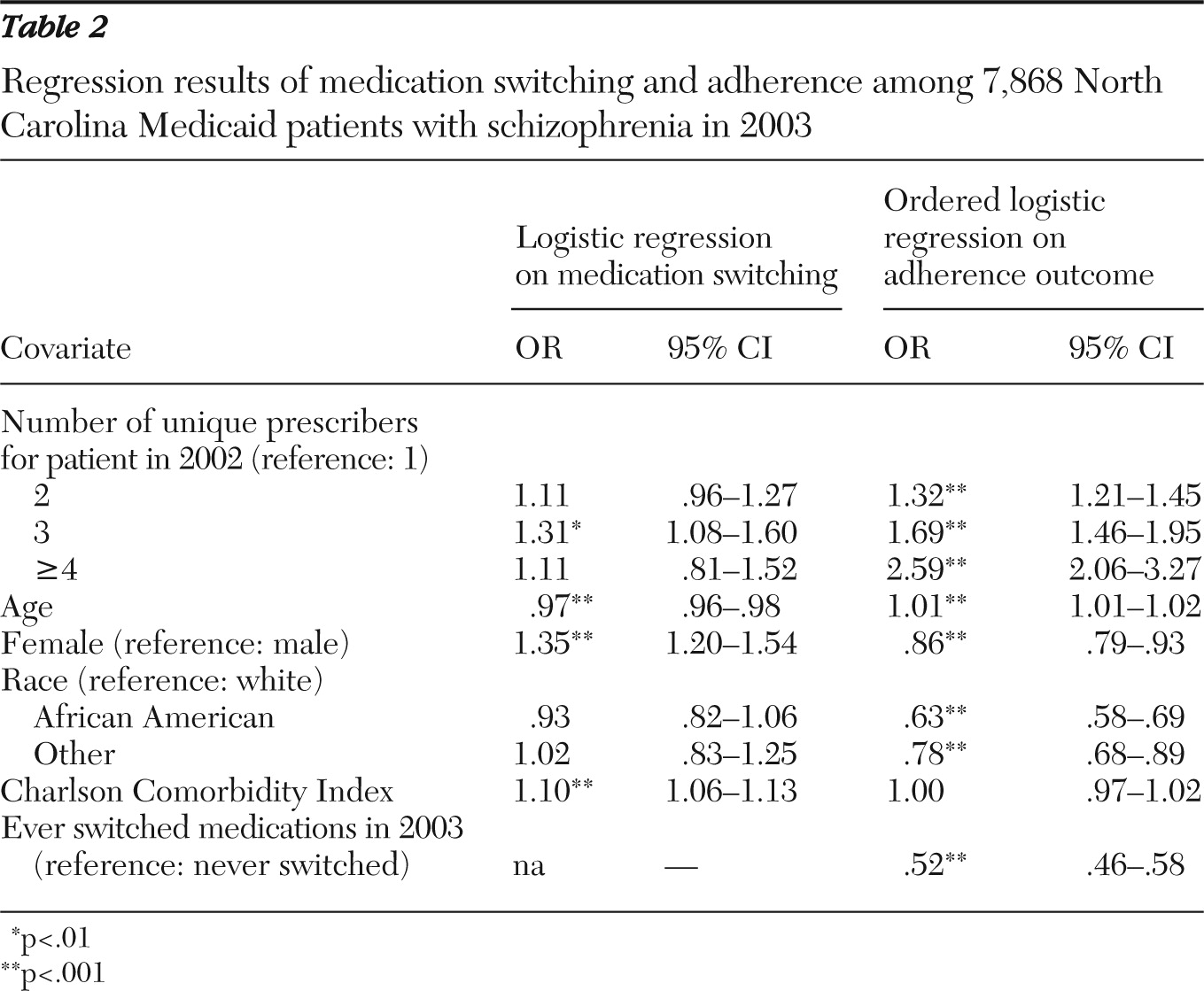

Results from a logistic regression to examine medication switching (

Table 2) showed that patients with multiple prescribers were more likely than patients with a single prescriber to switch antipsychotic medications, but this difference was significant only for patients with three prescribers (odds ratio [OR]=1.31). Patients were also more likely to switch antipsychotics in 2003 if they were female (OR=1.35) or had a greater comorbidity burden as indicated by the Charlson comorbidity index (OR=1.10). Older patients were less likely than younger patients to switch medications (OR=.97).

Results from the ordered logistic regression indicated that patients with more prescribers were more likely to be fully adherent or excess fillers compared with patients with one prescriber (

Table 2). Of the four patient groups, those with four or more prescribers were the most likely (OR=2.59) to be fully adherent or to be classified as excess fillers, followed by patients with two prescribers (OR=1.32) and those with three prescribers (OR=1.69). Older patients were more likely (OR=1.01) than younger patients to be fully adherent or to be excess fillers. Women (OR=.86), African Americans (OR=.63), patients of other races (OR=.78), and patients who switched medications (OR=.52) were less likely than other patients to be fully adherent or excess fillers.

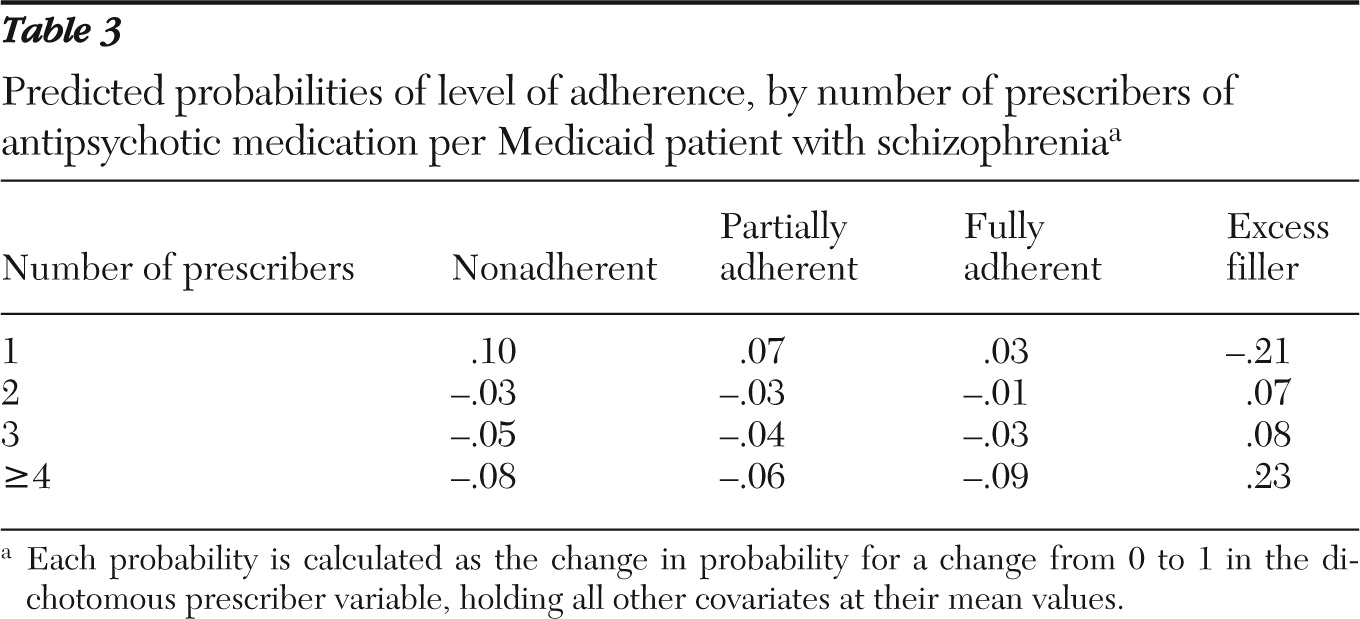

After analyses adjusted for patients' demographic factors, comorbidity, and switching behavior, we found that having one prescriber increased the probability of being nonadherent by 10% and the probability of being partially adherent by 7%, but it decreased the probability of being an excess filler by 21% (

Table 3). Having two prescribers or three prescribers increased the probability of being an excess filler by 7% and 8%, respectively. Having four or more prescribers increased the probability of being an excess filler by 23% but decreased the probability of being nonadherent by 8%, decreased the probability of being partially adherent by 6%, and decreased the probability of being fully adherent by 9%.

Discussion

This was the first study to examine number of prescribers and its association with antipsychotic switching and refill behavior among patients with schizophrenia. We hypothesized that as a result of poorer continuity of care and clinical information, patients with more prescribers would be less consistent in refilling prescriptions compared with patients seeing a single prescriber. Compared with patients with a single provider, those with multiple prescribers were found to have a higher probability of being nonadherent, partially adherent, or fully adherent to treatment. This finding suggests that having a single prescriber increased the probability of being nonadherent and decreased the probability of having excess fills. Our estimates of overfilling among patients with multiple prescribers may partly be a function of the adherence measure that was used in this study, such that medication switching and polypharmacy may increase the adherence values estimated by our measure in those instances.

Suboptimal medication adherence can have significant clinical consequences for patients with schizophrenia, such as poor treatment response for both positive and negative schizophrenia-related symptoms (

3). This nonresponsiveness to treatment may result in schizophrenia symptom relapses and higher rates of hospital admission (

2). One study suggested that antipsychotic treatment gaps lasting 30 or more days may result in a fourfold increase in the risk of psychiatric hospitalization (

5). In addition to adherence problems associated with reduced antipsychotic utilization, excessive antipsychotic utilization resulting from lack of care coordination may also be a clinical concern. Despite the widespread use of multiple concomitant antipsychotic treatments (

14), it has been suggested that antipsychotic polypharmacy should be reserved as a last resort, after all other treatment options have failed (

15). This suggestion is supported by a lack of evidence of the clinical benefit of polypharmacy and evidence to suggest that high-dose prescribing of antipsychotics and antipsychotic polypharmacy may increase sudden cardiac death (

16). In addition, excess use of antipsychotic medications is costly. Finally, a prior study showed that psychiatric hospitalizations, general medical hospitalizations, and total health care costs are higher for patients with schizophrenia who fill antipsychotic prescriptions excessively compared with those who fill them in a timely fashion (

7).

Four observations from this study warrant further investigation. First, it appeared that patients seeing one provider filled fewer antipsychotic prescriptions, which translated into more nonadherence and fewer excess fills compared with patients seeing multiple providers. Further investigation is needed to understand whether this refill pattern is appropriate for individual patients. Second, given that having multiple prescribers of antipsychotic medications was associated with less frequent filling and excessive filling, future research should be conducted to determine whether clinicians (particularly those with access to electronic medical records) should consider enrolling patients into medical homes so that their conditions and treatment records are available to all prescribers. This may improve communication between providers and continuity of care for patients with multiple prescribers. Medical homes and electronic medical records may be particularly effective for increasing the continuity of medication management and reducing therapeutic duplication for patients with schizophrenia because these patients frequently visit both primary care providers and psychiatric specialists.

Third, the finding that having multiple prescribers is associated with oversupply of medication should be examined in other chronic conditions and other insurance groups. For example, prior work has shown that patients' oversupply of antihypertensive medications is associated with suboptimal blood pressure control among veterans (

17). Fourth, future research should examine whether clinical and economic outcomes differ among patients with varying numbers of prescribers. Given that 43% of this sample had two or more prescribers of antipsychotic medication, there appears to be significant room for improvement in the continuity of medication management. Interventions that reduce the number of prescribers or improve care coordination for patients with schizophrenia who are seeing multiple providers may help achieve optimal refilling by reducing switching, nonadherence, and excess filling. If clinical and economic outcomes are better for patients with one prescriber, then the case for medical homes with a single prescriber is more compelling because care coordination, medication management, clinical outcomes, and economic outcomes would be optimized.

This retrospective analysis of Medicaid claims data is subject to several limitations. First, the results may not generalize to other states or to more recent years because these results are based on 2003 North Carolina Medicaid data. In addition, the results are limited to continuously enrolled Medicaid beneficiaries with full Medicaid benefits. Patients with noncontinuous enrollment may have had lower adherence, which we were unable to examine. Second, the medication adherence outcome reflects the number of days of medication supplied over the year interval. The MPR assumes medication consumption once a prescription is filled and thus is a proxy for adherence. In addition, the MPR may be sensitive to medication switching if patients are told to discard unused medication when filling a new prescription. This switching behavior may be more common when patients see multiple prescribers. However, we found medication switching to be associated with lower adherence in this study. Third, the pattern of prescriber visits was not explored for patients with two or more prescribers, so it is not clear whether adherence problems were greater for patients who saw multiple providers simultaneously or patients who switched providers one or more times. Fourth, we were unable to distinguish clinically appropriate switching of medications and physicians from inappropriate “doctor shopping” in claims. Fifth, the number of patient covariates that could be included was limited because of our reliance on Medicaid claims alone. Finally, there may be differences in unobserved patient factors that we were unable to adjust for in our analyses.

Conclusions

The results from this study show that antipsychotic prescribing by multiple physicians may increase the likelihood of both overuse and underuse of antipsychotic prescriptions. This suggests potential discontinuity in the coordination of psychiatric care for patients with schizophrenia. Increased attention has been given to methods of improving coordination of care through models such as the patient-centered medical home. Future research should examine the effect of these practice models as a means to improve continuity of medication management.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by the Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development Service, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the VA, or Duke University.

Dr. Farley, Dr. Hansen, and Dr. Maciejewski have received consultation funds from Takeda Pharmaceuticals and Novartis. The other authors report no competing interests.