To address this gap in knowledge, the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health sponsored a demonstration project to gain understanding of the process of implementing a collaborative care model at community health centers. In a separate report that was based on findings from the project, we found that patients who were older, more depressed, and more anxious were more likely to receive high-quality care and that patients with Spanish language preference and lower anxiety had the best outcomes (unpublished data, Bauer AM, Azzone V, Goldman HH, et al, 2011). In this study, we analyzed the role of site on specific process measures of depression treatment (early follow-up and appropriate pharmacotherapy) and on clinical outcomes (depression improvement and remission).

Results

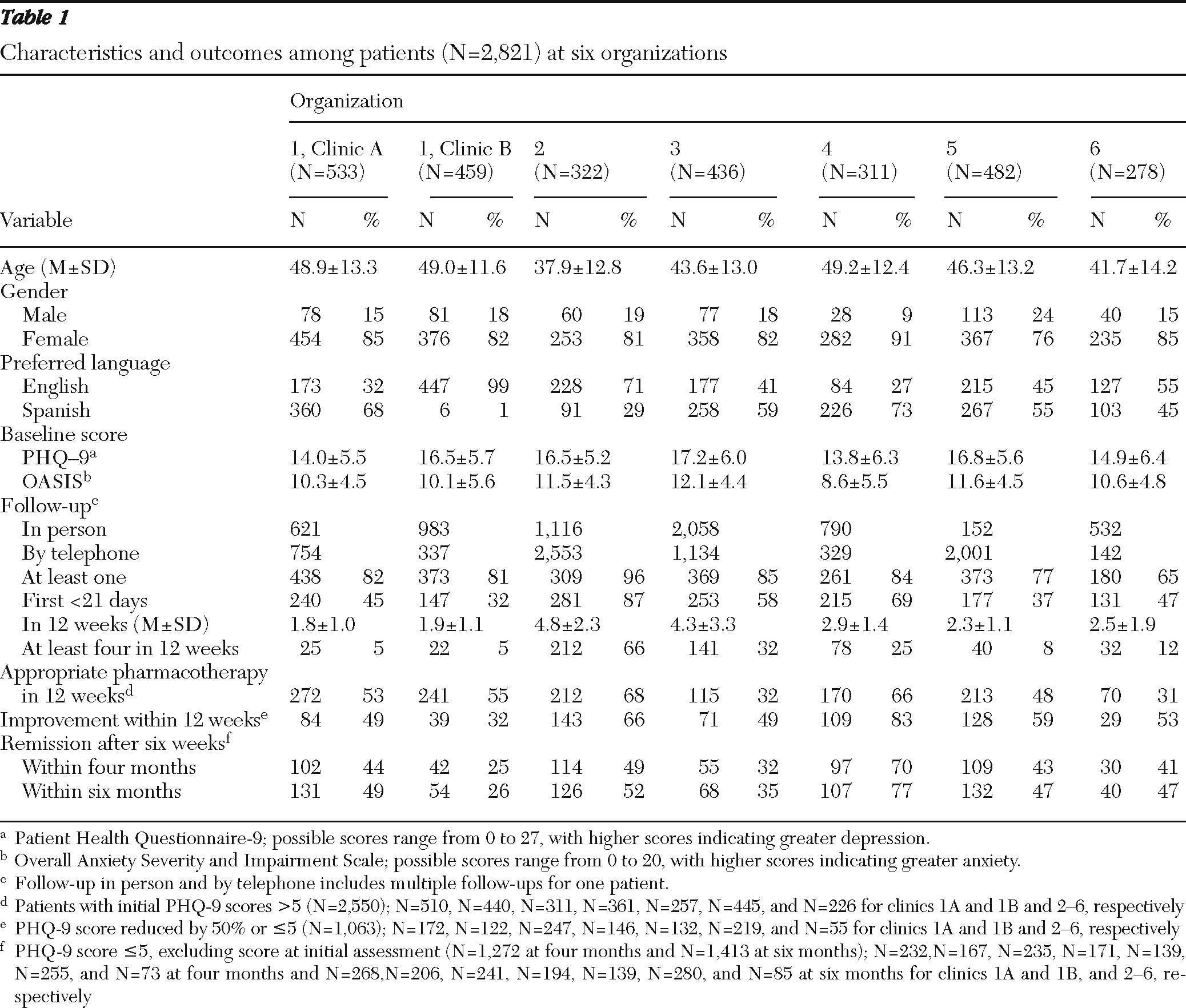

A total of 2,821 patients were identified as having symptoms of depression between 2006 and 2009 and were enrolled in treatment; they were predominantly female, ranged widely in age, spoke English or Spanish, and had moderate-to-severe depression and anxiety symptoms (

Table 1). Patients (N=271) who met criteria for remission at baseline as well as patients (N=540) for whom some predictor variables were missing were excluded from analyses of outcomes, resulting in a valid sample for the regression models of 2,010 patients.

Table 1 presents data for each clinic on the caseload, patient characteristics, and details of the treatment and outcomes.

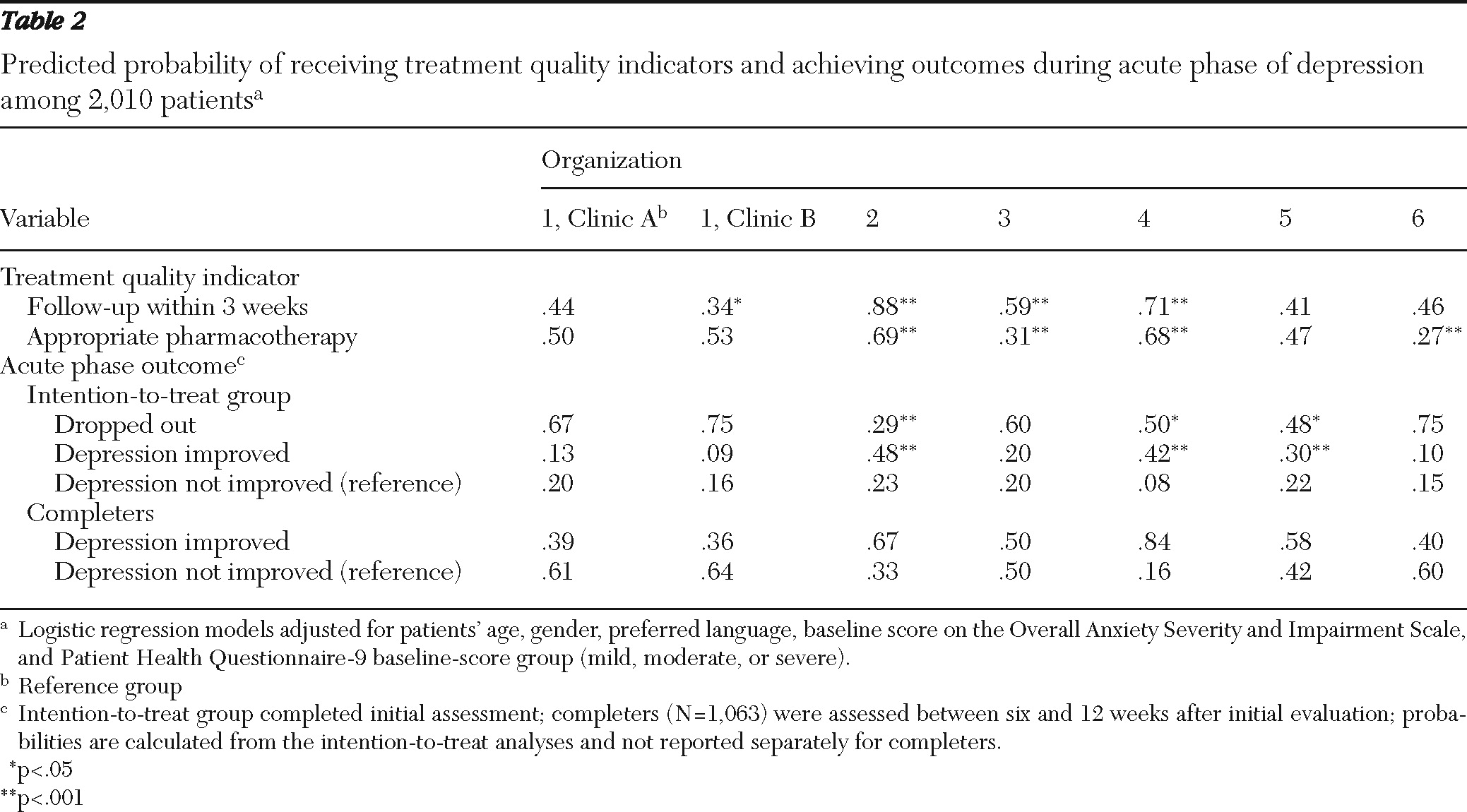

Both quality indicators were strongly associated with site (

Table 1), differences that were not attributable to characteristics of the patients served (

Table 2). On the basis of multivariate logistic regression models, the adjusted probability that a patient received an early follow-up contact ranged from .34 to .88, whereas the adjusted probability for receipt of appropriate pharmacotherapy ranged from .27 to .69.

Depression outcomes at 12 weeks, four months, and six months varied substantially across clinics in unadjusted analyses (

Table 1). The multinomial logistic regression model revealed that after adjustments for patient characteristics, the probability of discontinuing treatment differed significantly across clinics (range .29–.75), as did the probability of improvement (range .36–.84) among patients (N=1,063) who had valid PHQ-9 scores between six and 12 weeks (

Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses examined whether the quality indicators could account for the differences observed in outcomes across site. The inclusion of the quality indicators in the multinomial model did not attenuate the effects of site on outcome (data not shown). Patients with early follow-up were less likely to drop out (odds ratio [OR]=.50, p<.001) and more likely to improve (OR=1.64, p<.01), whereas patients who received appropriate pharmacotherapy were less likely to drop out (OR=.73, p<.05) but were no more likely to improve.

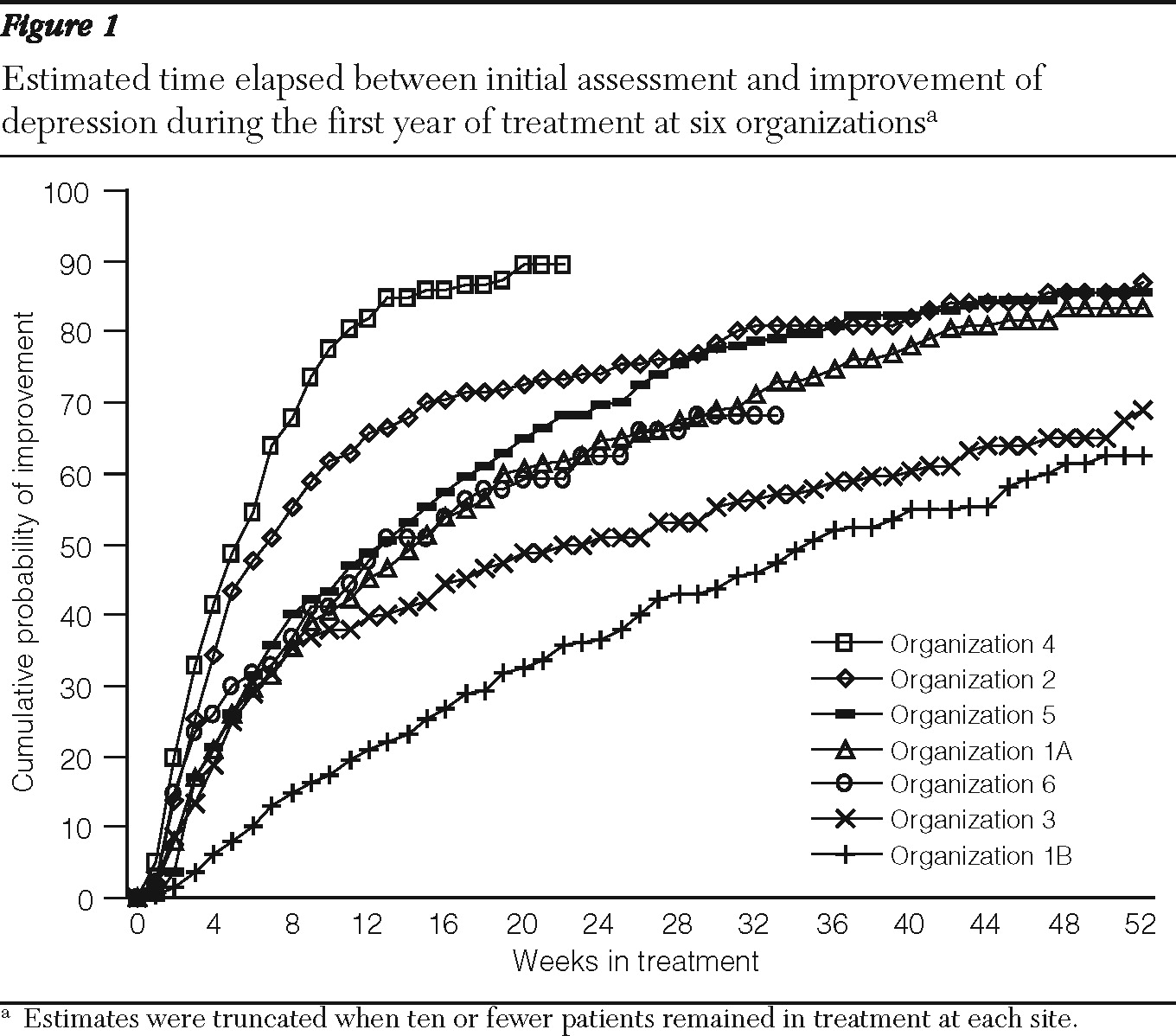

Survival analysis was used to estimate time to improvement across sites while accounting for censoring of patients who dropped out of care. The unadjusted survival curve,

Figure 1, illustrates that the proportion of patients who experienced improvement across clinics diverged as early as four weeks and that these differences persisted over time. Due to censoring, these results cannot be compared directly to rates of improvement reported in

Tables 1 and

2, although the findings are similar. Site differences in time to improvement remained significant after adjustment for patients' age, gender, preferred language, and baseline scores for depression and anxiety according to a Cox proportional hazards model (not shown).

Discussion

Overall, this demonstration project revealed that organizations with markedly differing characteristics were able to integrate mental health care into primary care for disadvantaged and underserved patients. In all sites, a plurality of patients experienced meaningful improvement in depression, and in some sites, the majority experienced rapid improvement following initiation of treatment.

Despite such broad successes, the organizations differed dramatically in indicators of quality and in outcomes, differences that were not attributable to the characteristics of the patients we measured. Moreover, the variability in quality measures and outcomes indicated that substantial room remained for improvement in quality of care.

Retention in depression treatment is poor for primary care patients, particularly among low-income members of minority groups (

24,

25). Outcome measures were collected exclusively in the course of clinical treatment and, therefore, were obtained at different times for different patients. Consequently, many patients who did not have a PHQ-9 score between six and 12 weeks were counted as dropouts for acute-phase outcomes, but only 18% were truly lost to follow-up, a rate that closely approximates retention in collaborative care research trials (

1,

3,

4,

26). Moreover, our survival models accounted for attrition in constructing estimates of outcomes over time.

In research on patients treated in a collaborative model, about 60% improved and 25% achieved remission during the acute phase, compared with rates for patients in usual care of about 40% and 10%, respectively (

3,

4,

26,

27). Depression outcomes are worse among patients whose conditions are complex, including the elderly, socioeconomically disadvantaged, anxious, or treatment resistant (

3,

4,

6,

26–

31).

Our results refuted the notion that trial results could not be reproduced by organizations in economically deprived, minority communities serving heterogeneous patients. Several participating organizations were federally qualified health centers in poor urban border towns that have high concentrations of Spanish speakers and were safety-net providers for uninsured individuals, including undocumented immigrants who are ineligible for Medicaid. At six of seven sites, half of patients improved, and at five sites more than 40% of patients achieved remission, a more challenging clinical target.

Thus, the results provided robust support to demonstrate that collaborative care, when adapted by community health centers, can meet or surpass the outcomes achieved in research settings, even in poorly resourced settings. This finding is highly relevant in light of strong interest in integrating health care in the context of national health care reform.

Although all organizations received the same training, guidance, and support and all used the same Web-based registry, the care provided and the outcomes achieved differed markedly. Outcomes diverged across sites as early as four weeks, highlighting the critical importance of the early course of treatment. For example, loss to follow-up occurred for only 4% of patients at organization 2, compared with more than one-third of patients at organization 6. Organization 2 was successful in all metrics of care; 87% of patients received early follow-up, 66% had four or more follow-up contacts within 12 weeks (average=4.8), and 68% received appropriate pharmacotherapy. Patients treated at this clinic had excellent acute-phase outcomes—two-thirds of patients improved, and half achieved remission. In contrast, the site with the worst acute-phase outcomes (organization 1, clinic B) performed relatively poorly on process measures. As many as 19% of patients were lost to follow-up, only one-third of patients received early follow-up, just 5% of patients received four or more follow-up contacts within 12 weeks, and approximately half of patients received appropriate pharmacotherapy.

Having conducted site visits, we had the impression that some sites implemented the collaborative care model more effectively than others. Those sites that appeared to implement well demonstrated better performance on both quality indicators and patient outcomes. These differences were not attributable to patient characteristics. Although early follow-up was significantly associated with improved outcomes, we were not able to conclude that more patients improved because they received more intensive follow-up. It is possible that the indicators we measured tapped into broader constructs of the quality of services provided across organizations and were not responsible for improved outcomes but, nevertheless, were associated with such outcomes.

In multivariate analyses adjusting for quality indicators, site remained strongly associated with outcomes, suggesting that the effect of being treated in a particular clinic is at least as salient as receiving (or not receiving) early follow-up or appropriate pharmacotherapy. On the surface that may appear surprising; however, it was consistent with our impression that the quality measures we quantified were indicators of broader processes occurring within the clinics. Similar patterns may have emerged if we had quantified other quality indicators. Clinics with better implementation may have been more likely to provide treatment intensification for patients not responding to initial treatments, effects that were not captured by our analyses. Similarly, clinics that achieved superior outcomes may have been more effective in tailoring treatment to individuals' needs, for example, by accounting for patient preferences, availability of services, and adaptation of treatment to individual outcomes.

Because a small number of organizations participated in this demonstration project, we were not able to quantitatively evaluate how characteristics of the organizations were associated with outcomes. However, because of the great interest in replicating collaborative care models in community settings, we speculate on some potential contributors.

Several organizations located in impoverished communities with no preexisting mental health services, little or no experience with integrated care, and few resources were largely successful in implementing collaborative care. In contrast, the organization that had the least success in program implementation was a large organization with a significant preexisting structure of mental health providers both within primary care and at specialty sites. Having a system in place that separated mental health and primary care appeared to impede implementation. Despite receiving training and additional resources, the organization appeared to make few changes to its practice, and care remained so fragmented among a wide array of providers that many patients “fell through the cracks.” Thus, building an integrated delivery model de novo may be more straightforward than reengineering a system of existing services.

Organization 4 provided an example of a success story. Although the leadership at this organization was unsupportive and at times antagonistic to the initiative, the organization had strong support from capable primary care providers and care managers who embraced the model. In this case, it appears that the clinicians were successful in enacting substantial practice change despite a lack of strong support from the administration. They engaged patients early on and provided appropriate pharmacotherapy to most of them. These examples suggest that paying attention to the preexisting system of care may be an important element for organizations to consider as they implement an integrated model and that getting buy-in from clinical providers on the ground may be particularly crucial.

In considering the implications of these findings, several limitations are important. First, unmeasured differences in the patient populations treated across sites may have accounted for some of the variability observed. Information was not available on patients' race-ethnicity, education, or income, factors that may be associated with depression outcomes. Because the organizations predominantly treated uninsured patients in impoverished communities, these results may not represent organizations treating patients under more advantaged circumstances.

Without having data on treatment patterns and outcomes at these organizations before the start of the initiative, we were unable to indicate to what extent the treatment and outcomes observed were the result of the introduction of this model. The patients treated represented a heterogeneous mixture of clinical presentations, and data on diagnoses were not available for further description. Analyses were also limited by a lack of detail about patients' use of psychotherapy and psychiatric consultation. Finally, medication data were obtained from the registry and may not have reflected patients' actual medication use.