In recent years, groups of similarly traumatized children have been studied for posttraumatic symptoms and signs. A group of kidnapped California schoolchildren, for instance, exhibited such symptoms as repeated dreams, event-specific fears, fears of the mundane, posttraumatic play, personality changes, psychophysiologic and behavioral reenactments, and diminished expectations for the future

(3–

5). These signs and symptoms were later found in various groups of children traumatized by different events

(6–

8). In a number of studies, however, symptoms have been found to fall short of the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

(8,

9). For example, an Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey of the heads of Midwestern households in 1987 found that 15% of the participants had had some symptoms of PTSD, although they did not meet the full criteria for the diagnosis

(10). A Los Angeles study of children exposed indirectly to a school playground sniper shooting while they were on rotating vacations found that these children fell just short of the diagnosis of mild PTSD

(11).

METHOD

Our methods have been described in detail in earlier reports on children’s memories and thinking after the

Challenger explosion

(1,

2). In brief, we considered children from Concord, N.H., and Porterville, Calif., a town that buses its students to school, as relatively well-matched communities for study and comparison. The hometown of Christa McAuliffe, Concord, N.H., had sent some of its children to Cape Canaveral to view the launch, giving us a third, smaller group for comparison.

In 1986 and 1987, one of us (L.C.T.) administered a 298-item, 45-minute structured interview of our own design

(22) to third- and 10th-grade students who had been selected by school officials using our random number tables and their complete school registration lists. We employed only one interviewer because the need to reach two communities within days of the disaster precluded the training and testing of additional personnel. A year later, we opted for consistency and used the same interviewer for the follow-up study. Because only one interviewer was used and because people at the interview locations were not blind to the purpose of the interviews, there was a possibility of either exaggerated or diminished interview responses.

Among the children selected for study, 90% returned written informed consent forms, signed by both parent and child. While waiting in a schoolroom for the interview to begin, each child was asked by one of us (S.M.) to draw or write something about Challenger. Only the children who were preliminarily determined (by S.M.) to have seen the explosion live (on the East Coast) or who had heard about it later (on the West Coast) were included in the study. Fewer than five children were eliminated on this basis.

The interviewer asked about background and health, emotional and learning problems, past traumatic experiences, and responses to

Challenger. Many of the questions had to do with memory

(1) and thinking

(2). Others had to do with childhood symptoms of bereavement

(23). The interviewer also inquired into a variety of behavioral and physical problems, anxieties, and habits. Symptoms of PTSD were explored in depth. With such complex symptoms as play or dreams, the child was first asked a yes/no question—for instance, “Have you had dreams about

Challenger since the explosion?”—then the child was asked for an estimate of the frequency of dreams, and then the child’s verbal descriptions were recorded.

To the main study group of 124 children we added nine Concord third-graders and one Concord high school student, a self-selected group that had watched the launch from the Cape Canaveral viewing stands. We added another 19 students from the Concord and Porterville schools from which students had been previously drawn; they had been chosen randomly at the schools in 1986 but were placed into our study in 1987 as an interview comparison group in order to help determine if the interviews of 1986 had promoted or diminished any symptoms in the larger group of 124. We lost one child from the study in 1986 and five children in 1987 (a 1-year retention rate of over 95%).

Recording and grading of interviews was done by using a number code for the subjects, schools, and locations. We then used standard statistical tests, setting up a frequency table expressed in percentages, and placing each child into two groups out of a possible four—East Coast (involved, watched live television) and West Coast (less involved and heard later); and latency-age children and adolescents. To compare the groups, we employed Yates’s continuity-corrected chi-square tests with one degree of freedom. To compare children when any of the cell frequencies were less than 5, we employed Fisher’s exact test. To compare the groups’ symptomatic changes from 1986 to 1987, we used two-sample t tests in which the dependent variable was change. To determine which symptoms children reported 14 months after the explosion compared with the symptoms that those same children had reported 5–7 weeks afterward, we used paired-comparisons t tests (matched pairs). We made no attempt to gauge the emotional intensity of any particular finding; however, the frequency of symptoms provided some data on this.

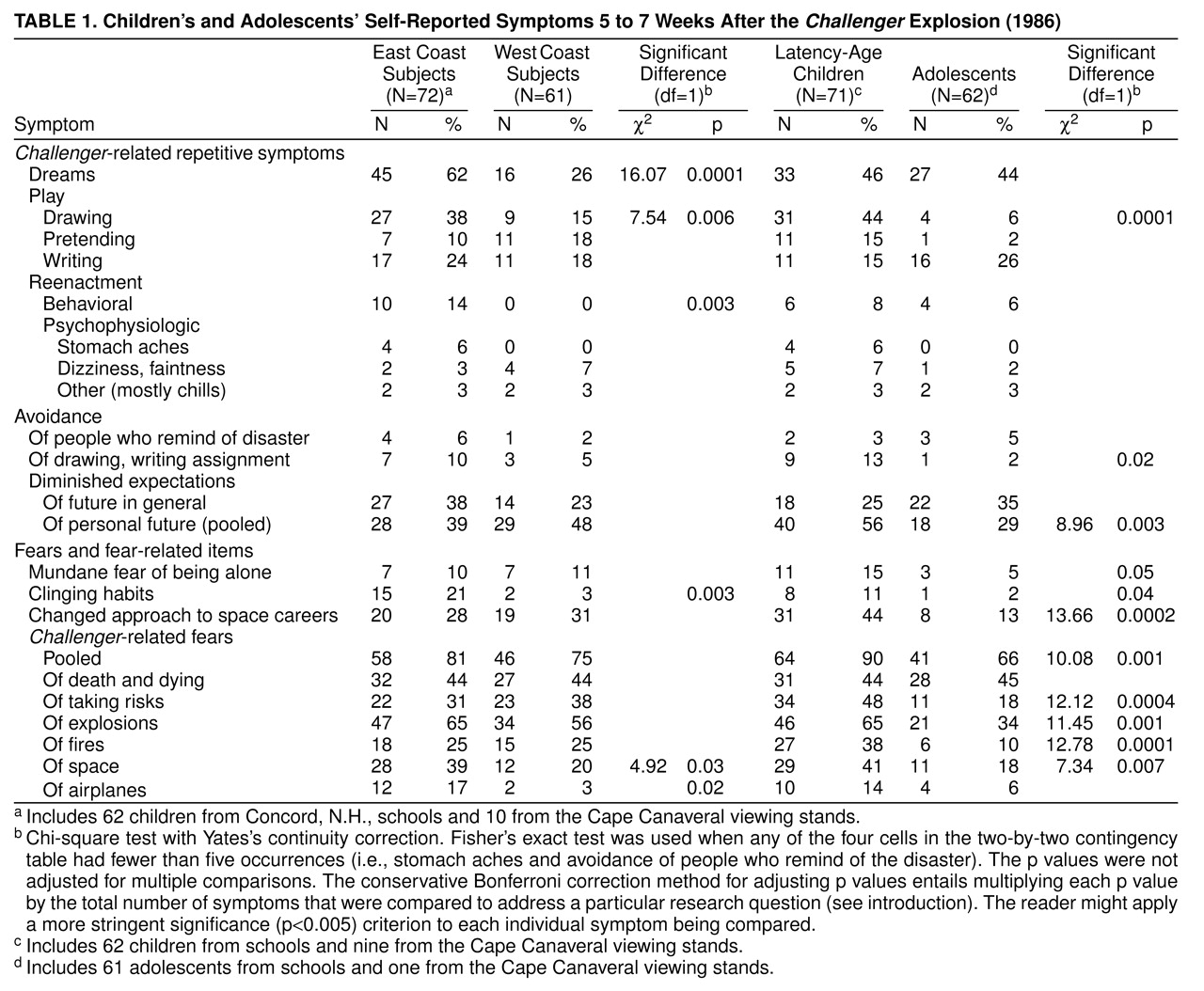

We asked a great number of questions, and the p values reported were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. The reader may wish to calculate Bonferroni corrections, as suggested in

Table 1, footnote b. If one uses p<0.005, instead, as a more stringent alternative, one may recognize that although adjustments could be made for multiple comparisons, a number of the findings in this study attain this more exacting level of significance. We emphasize those particular findings in our Results and Discussion.

DISCUSSION

The Challenger interviews attempted to discover what symptoms children at two stages of development and with three kinds of exposure would develop following a shocking, but not personally threatening, event. The interviews could not be blind; a large number of questions were asked. However, even in using a particularly stringent p value of 0.005, we found that East Coast and latency-age children were initially significantly more symptomatic than West Coast children and adolescents. There was more dreaming, drawing, behavioral reenactment, and clinging in the East Coast group. There was more drawing, diminished life expectations, new approaches to space careers, and event-specific fears among latency-age children. Three of our latency-age child subjects would have qualified for the diagnosis of PTSD within the first year if not for their failure to meet the first criterion for PTSD—having endured a traumatic event.

The concepts of subthreshold and spectrum PTSD are new and are thus far unique, as far we can tell, to this article. We would not have been comfortable labeling any of our subjects as having subthreshold PTSD, however, because they did not go through an event personally directed at them. That term should be reserved, we suggest, for children who experience sexual or physical abuse, kidnappings, accidents, natural disasters, massive or painful surgeries, or cancer and its treatments—in other words, direct events—yet who miss meeting the full symptomatic criteria for PTSD.

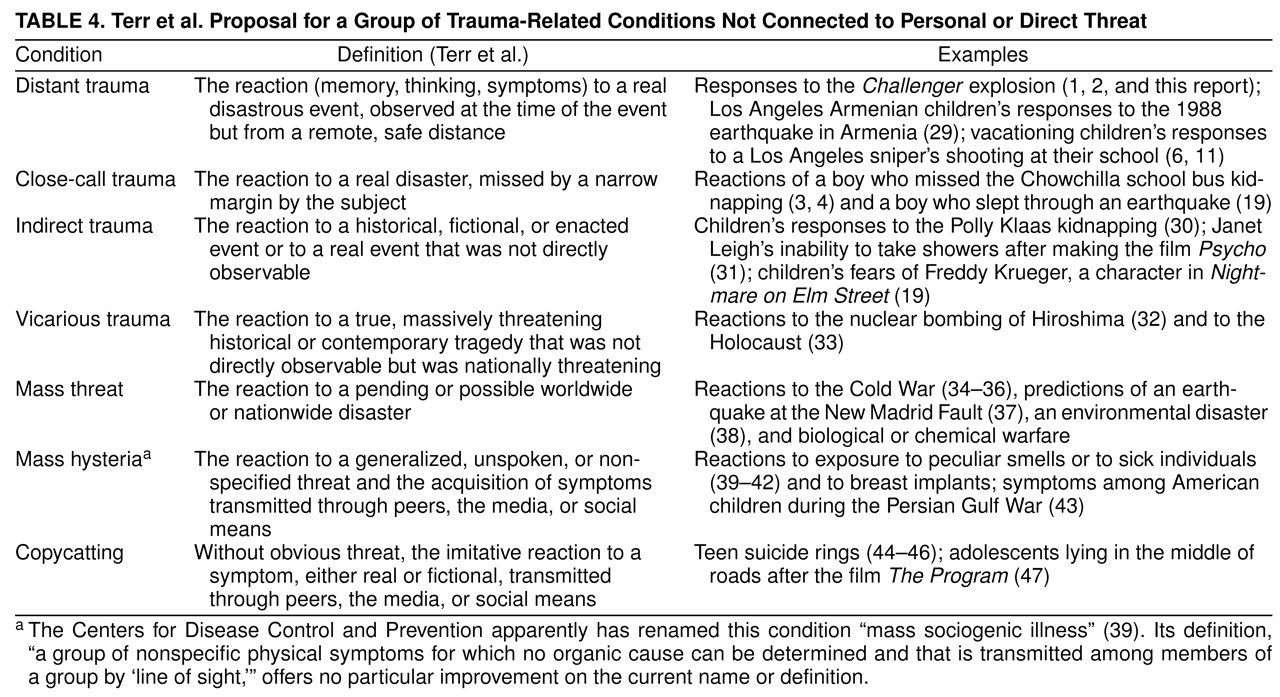

Trying to find terminology, therefore, for what happened to American schoolchildren after the Challenger explosion was difficult because none of the subjects went through a personally threatening experience. We believe that a second category, spectrum—one that has recently gained favor in the mood and anxiety field—may apply here. If we call what happened to the Challenger subjects “distant trauma,” if we define their responses as “the reaction (memory, thinking, symptoms) to a disastrous event, experienced at the time of the event, but from a remote and realistically safe distance,” we might also propose that distant trauma be considered part of a broad range of trauma-related conditions, or the “trauma spectrum.”

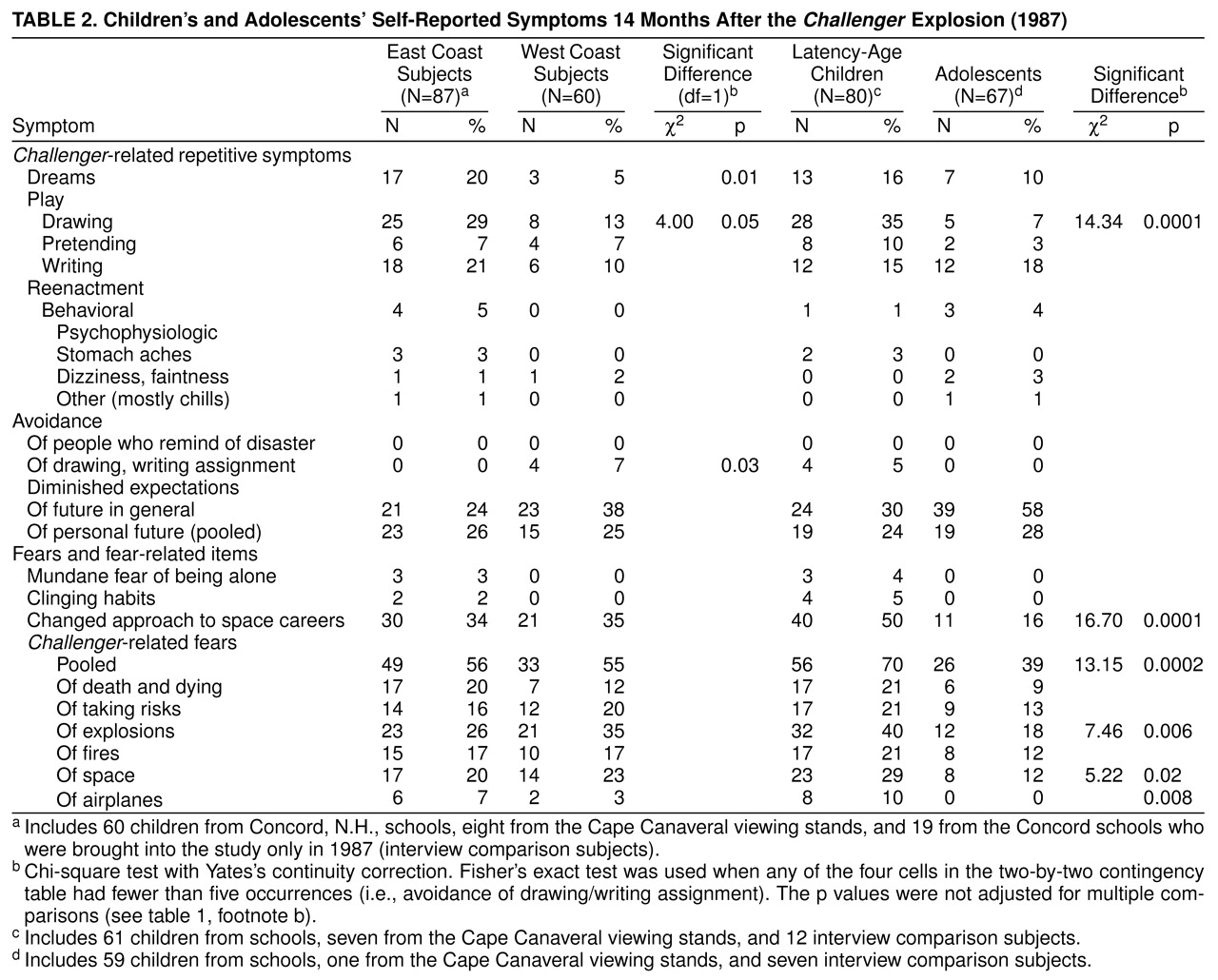

What should distant trauma consist of? Here, our data on symptoms from this

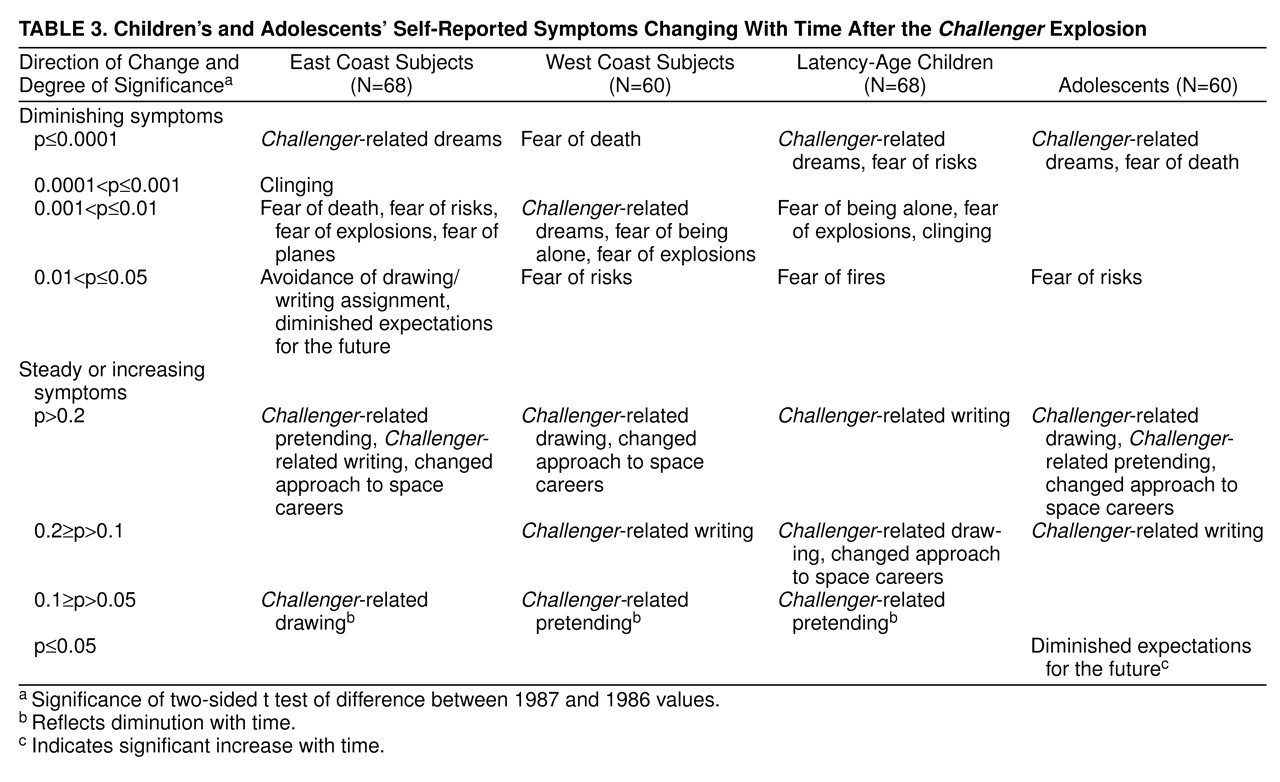

Challenger study should be useful. We found that dreams, posttraumatic play (writing, drawing, pretending), trauma-specific fears (death and dying, taking risks, explosions, fires, space, airplanes), trauma-related approaches to space careers, and diminished expectations for the future were the most likely symptoms to appear within the first few weeks following this horrifying, far-off event. After a year had passed, we found lingering fears, posttraumatic play, new approaches to related careers, and diminished expectations for the future. In fact, there were a few symptoms that appeared particularly difficult to shake. If a child initially started posttraumatic pretending, drawing, or writing, for instance, that child could very well continue that activity over a year’s time. This lasting quality of posttraumatic play has previously been noted in a study of children with clinically diagnosed trauma

(21). If a latency-age child initially changed his or her expectations for a career in space, these expectations also tended to hold. In adolescents, gloomy attitudes about the general future significantly gained momentum (

Table 3). Thus, even though posttraumatic fears and dreams were likely to spontaneously disappear at what seems to be a significant rate, some fears, play, and a sense of diminished expectations for the future might easily persist into a second year.

Three symptoms not previously appearing in our diagnostic manuals for PTSD are of special interest in this study. The first of these is trauma-specific fear, a finding evident in 90% of latency-age subjects 5–7 weeks after the

Challenger explosion. In fact, despite the observation that over time these fears diminished in incidence, large numbers of children and adolescents continued to harbor at least one event-specific fear for more than a year. The fear of being left alone and the habit of clinging to others were also important enough in this

Challenger study that they should be taken into account whenever a physician or mental health worker considers a trauma-related condition, especially in a child under 10 years of age. As a matter of fact, clinging and the fear of being left alone are closely connected in infants and toddlers with disorders of attachment

(24–

26), conditions that very likely would be considered part of a trauma spectrum were the idea to take hold.

Event-specific fears were the most common indication that the children in our study had been affected by the explosion in space. This corresponds to findings from a Los Angeles schoolyard sniper attack, indicating that fears of another shoot-out, although highly prevalent, did not significantly separate the children who had been under fire from the children who were away from school

(11). It appears that when children under 10 become intensely concerned about an external event, distant or not, they have a high likelihood of developing an event-specific fear.

One might wonder what causes latency-age children to be significantly more symptomatic than adolescents. One might also wonder why we found that thinking and attitude changes were significantly more common in teenagers than in the younger groups

(2). The answer probably lies in a reciprocal relationship between emotions and thought. Adolescents, who have already lived through a few other distant events, are probably more able to think through a tragedy by employing the larger context of their other unpleasant experiences

(27). Through thinking it out, they may be able to spare themselves overwhelming emotions and resultant symptoms. Latency-age youngsters, on the other hand, more easily experience raw emotion and confusion. They occasionally regress. Perhaps these factors increase the possibility of symptom appearance. After the

Challenger explosion, adolescent thinking was not entirely protective. While their pessimistic attitudes tended to grow over time

(2), their diminished expectations for the future in general significantly gained new believers (

Table 3). Thus, the teenagers in this study were not at all spared the effects of the events in space; their experience was simply different from that of the younger children.

Because the question of what makes people vulnerable to trauma is not settled, we were interested in whether the previously trauma-exposed children in our study would be more or less prone to symptoms than the children who admitted to experiencing no previous traumatic events. In two respects—those of pooled fears and behavioral reenactments—they were less symptomatic. While they harbored a symptom—diminished expectations for the future—that did not fade dramatically with time, these children’s future visions had probably been curtailed, in large part, by their earlier traumas, not by the

Challenger disaster. Multiple traumas are already widely known to cause serious psychopathology

(28). But distant traumas, when added to personal ones, may not have the same effect.

The symptomatic similarity of the 19 children withheld from the study until 1987 to the children interviewed in both 1986 and 1987 showed us that our interview probably exerted no deleterious effect. Despite a belief among the general public that children should not be studied after upsetting events, our interview comparison group was no more and no less symptomatic than the group of children who had been interviewed in 1986.

It might be interesting to speculate here whether distant traumatic exposures, like that of

Challenger, play a part in ordinary short-term human development. Our findings suggest that they do. Distant traumas might be grouped into a superstructure of mental conditions involving no personal or direct threat that are commonly encountered in the course of a lifetime. We have listed, defined, and exemplified these in

Table 4. The reader may call this the “trauma spectrum.” This grouping includes, among others, distant traumas (similar to that of

Challenger), close calls or near misses, indirect traumas, vicarious traumas, mass threats, mass hysterias, and copycat syndromes. Every symptom in these closely related conditions has not yet been described. From this particular study, a set of memory

(1), thinking

(2), and symptomatic findings begin to characterize one of these conditions—distant trauma.

Challenger shows that those who initially watched and who were the most emotionally concerned with this tragic, distant event tended to suffer the most. Within this general framework, however, small differences in distance and emotional involvement (such as being in Cape Canaveral versus being in Concord watching television) appeared to make little difference. We conclude that for children raised from birth with television, the immediacy of the medium seems almost as real as pure, untouched reality.

One of our 8-year-old Cape Canaveral subjects was quoted by a reporter on the 10th anniversary of the

Challenger tragedy

(48):

“When the sky is that certain blue of the day of the launch, I always think of Challenger. But you always recover. You move on.”

— Boy, age 18, Concord, N.H., 1996