Clinicians are frequently confronted with elderly people who complain about their memory. Although memory complaints are common in older people, the validity of these complaints has been debated

(1–

9). A clinically relevant question is whether memory complaints precede observable dementia and, in particular, Alzheimer’s disease. Cognitive decline is often a gradual process, and it may take years before diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease are met. Prospective studies involving clinical samples found no association between memory complaints and subsequent cognitive decline or dementia

(10,

11). Population-based studies have reported divergent results. Jorm et al.

(12) found no association between cognitive complaints and future dementia, whereas Tobiansky et al.

(13) did find such an association. In our study, it was also found that memory complaints preceded dementia

(14,

15). Moreover, the association remained after adjustments were made for depression, which suggests that memory complaints reflect realistic self-observation of cognitive decline

(15). However, no differentiation was made between subjects with normal cognition and those with impaired cognition. In a recent study, Schofield et al.

(16) found that memory complaints predicted subsequent cognitive decline in nondemented elderly people with baseline cognitive impairment but not in those with normal baseline cognition. This association was most apparent among subjects with a higher level of education and suggests that they showed a significant decline from a previous level of cognitive functioning

(16). Thus, the results of these prospective studies suggest that memory complaints may be a strong predictor of cognitive decline and incident dementia among elderly people in whom cognitive impairment may already be apparent.

It could be hypothesized, however, that memory complaints could also predict incident dementia among older persons in whom cognitive impairment is not yet apparent. Elderly people may notice that their memory deteriorates at a time when cognitive tests are still unable to verify any change in cognitive functioning. The follow-up period should, therefore, be long enough to make it possible to find an association between memory complaints and incident dementia in subjects with no signs of cognitive impairment. This may particularly apply to dementia of the Alzheimer’s type, which is characterized by an insidious onset and slow progression. The objective of the present study was to investigate whether memory complaints predicted developing Alzheimer’s disease among elderly subjects with normal cognition. The study population was a large cohort of randomly selected, noninstitutionalized elderly individuals; the average follow-up period was 3.2 years. In contrast with our previous studies

(14,

15), the study sample included elderly subjects with normal cognition, as well as those with borderline and impaired cognition. Furthermore, in contrast with the previous studies, memory complaints were assessed with a single question.

METHOD

Baseline Sample and Measurements

The sampling procedure and nonresponse of the baseline population of the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly have been described in more detail elsewhere

(17,

18). In brief, 5,666 noninstitutionalized elderly people, 65 to 84 years old, were selected from 30 general practices spread across the city of Amsterdam. In the Netherlands, general practitioners are the gatekeepers to the health care system, and almost all noninstitutionalized people are registered in a general practice. Within each practice a fixed proportion of persons was randomly selected from each of four 5-year age strata (65–69 years to 80–84 years) to obtain equal-sized strata. Age and sex of the general practice population did not differ from the corresponding general population of Amsterdam. Of the 5,666 persons sampled, 4,051 (71.5%) gave their written consent after the procedures had been fully explained and participated in the study; 23.9% refused to participate; and 4.6% could not be contacted because they had died, become institutionalized, or moved away from Amsterdam. Nonresponders had poorer health and cognitive status than responders, but these differences were more pronounced among the younger old (less than 75 years old)

(18).

From May 1990 to November 1991, trained lay persons interviewed all 4,051 participants at home. The interview consisted of questions on sociodemographic characteristics, current health status, and medical history. Memory complaints were assessed with the question “Do you have complaints about your memory?” Answers were coded in four categories (no; sometimes, but is no problem; yes, is a problem; yes, is a serious problem). To evaluate cognitive functioning, four mental status tests were administered

(19–

22). Level of education (highest grade completed) was measured on an 8-point ordinal scale, ranging from uncompleted primary school to completed university education. The educational levels were dichotomized at the median of the sample selected for this study (see later discussion) into lower levels of education (uncompleted primary school to partial secondary education) and higher levels of education (lower vocational education to completed university education). This is comparable with approximately 8 years or less and 9 to 18 years of education, respectively. To evaluate the presence of depression, the Dutch version of the Geriatric Mental State Schedule (community version)

(23–

25) was used in conjunction with its computerized diagnostic system, AGECAT

(26–

28). The Geriatric Mental State Schedule is a structured interview specifically designed for use with elderly individuals. The AGECAT computer program consists of the application of hierarchical rules to the items of the Geriatric Mental State Schedule in order to achieve a diagnosis for several psychiatric disorders (such as depression and organic illness) with different levels of confidence. Syndrome levels of 0–2 indicate the absence of depression, whereas levels of 3–6 indicate the presence of depression. Studies of community-dwelling and hospitalized elderly patients that compared Geriatric Mental State Schedule-AGECAT depression syndrome levels of 3–6 with DSM-III-R diagnoses of depression showed that these levels identify both major depression and dysthymic disorder

(29,

30).

Study Sample

The present study sample was selected by excluding all subjects who were diagnosed as having dementia according to the criteria of either DSM-III-R or the Geriatric Mental State Schedule-AGECAT (N=273). The procedures of the diagnostic evaluation at baseline have been described in more detail elsewhere (14, 31). For the clinical evaluation according to DSM-III-R criteria, a subsample was selected on the basis of performance on the Mini-Mental State (19). This subsample consisted of all persons with Mini-Mental State scores of 21 or less, as well as randomly selected, age-stratified samples of those with scores of 22–26 (approximately 45%) and 27–30 (approximately 7%). With respect to the definition of dementia according to the Geriatric Mental State Schedule-AGECAT (which was administered to all persons in the baseline sample), Geriatric Mental State Schedule organic illness syndrome levels of 3–5 indicate the presence of dementia, whereas levels of 0–2 indicate the absence of dementia. The remaining 3,778 nondemented persons who formed the study sample were divided into two categories: normal cognition (defined as Mini-Mental State scores of 26–30) and borderline and impaired cognition (defined as Mini-Mental State scores of 25 or less).

Follow-Up Measurements and Diagnostic Evaluation

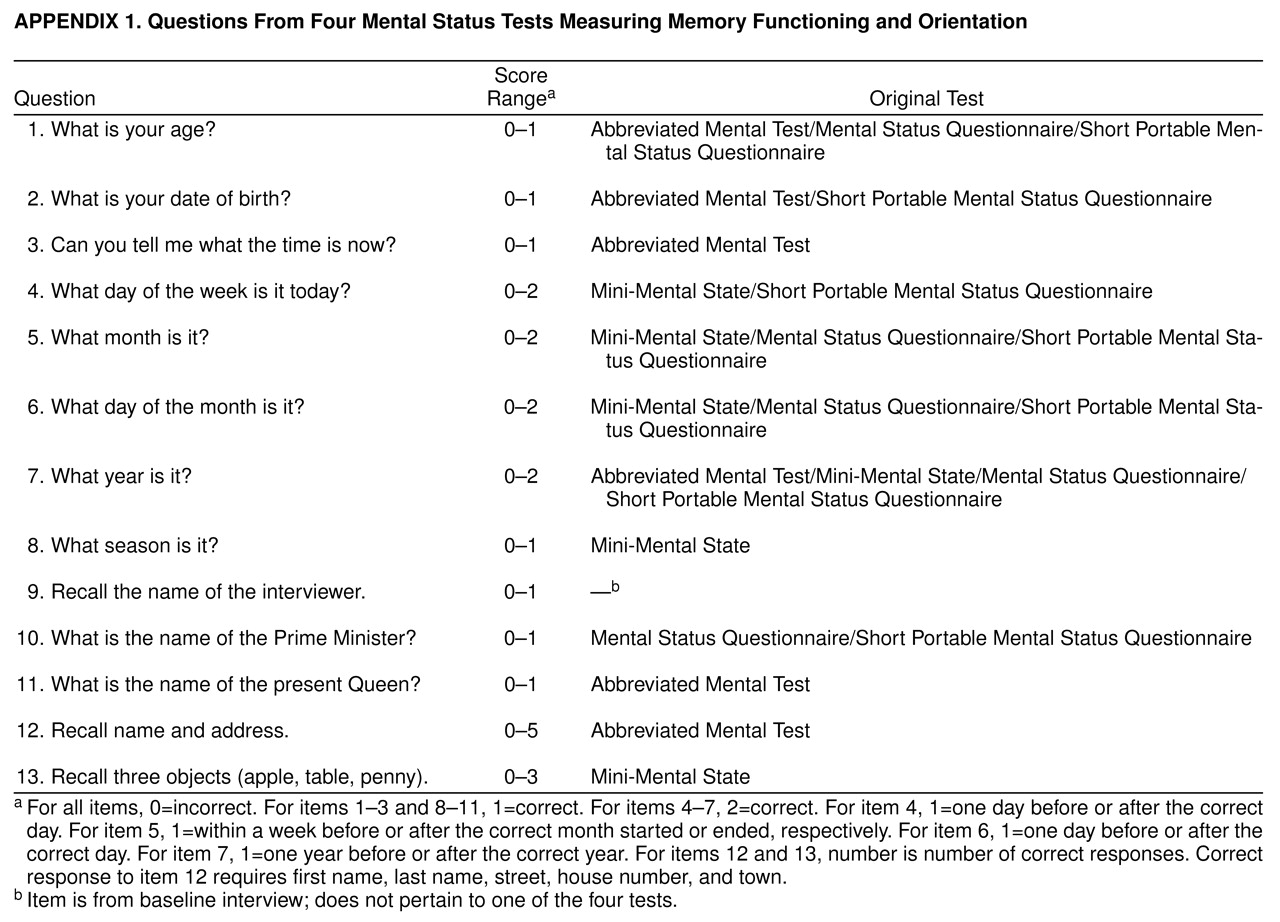

At follow-up, which took place from February to October 1994, all subjects who were available were interviewed again by trained lay persons who used the same interview procedure as that employed in 1990–1991. Subjects were selected for further diagnostic evaluation if their Mini-Mental State scores were 23 or less or if they had low scores on a memory test. The second test consisted of the relevant items from the four mental status tests

(19–

22), measuring orientation, recent memory, and learning. This involved a total of 13 questions, with a maximum score of 23 (appendix 1). The memory scale’s reliability, indexed by Cronbach’s alpha (i.e., internal consistency), was 0.71 in the baseline sample. The cutoff score of the memory test was set at 18. This was the cutoff that selected all patients with prevalent Alzheimer’s disease at the baseline diagnostic evaluation. Thus, in addition to all subjects with Mini-Mental State scores of 23 or less, all subjects with memory scores of 18 or less were selected for further diagnostic evaluation.

For this diagnostic evaluation, which took place from April to August 1996, all subjects who were available were visited at home by physicians who were specifically trained for this purpose. The procedures and measurements were analogous to those at the baseline evaluation. Subjects underwent the Cambridge examination for mental disorders in the elderly (including a structured psychiatric interview, the Cambridge Cognitive Examination, and a physical examination)

(32). Additional questions were included to assess (instrumental) activities of daily living

(33, >

34). Clinical diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia were made according to the respective DSM-IV criteria. Diagnoses were determined during weekly meetings with the senior neurologist (C.J.) and the neuropsychologist (M.I.G.).

Statistical Analyses

The statistical analyses were performed in SPSS for Windows (version 7.5). All subjects who were diagnosed with dementia other than the Alzheimer’s type were excluded from the analyses. To assess whether memory complaints were associated with incident Alzheimer’s disease, multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed with memory complaints as the independent variable and incident Alzheimer’s disease (yes versus no) as the outcome variable. The four answer categories regarding memory complaints were dichotomized into “no” (no; sometimes but is no problem) and “yes” (yes, is a [serious] problem). Potentially confounding variables included in the multivariate analyses were age stratum at baseline (75–84 years versus 65–74 years), sex, level of education (low versus high), depression (yes versus no), and cognitive category (borderline and impaired versus normal). To investigate whether the association between memory complaints and incident Alzheimer’s disease was modified by cognitive category, educational level, or depression, interaction terms were included in the multivariate models. Reference groups for indicator variables were no memory complaints, younger age stratum, male sex, higher level of education, no depression, and normal cognition.

RESULTS

The follow-up period was 3.2 years, on average. At follow-up, 2,169 persons were available for interview (57.4% of 3,778), of whom 433 were selected for further diagnostic evaluation; 267 persons actually underwent diagnostic evaluation and 77 were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease; 13 had developed vascular or secondary dementia and were therefore excluded from the analyses. The mean total Cambridge Cognitive Examination score of the Alzheimer’s disease subjects was 57.6 (SD=12.8) (maximum score is 107; a cutoff score of 79–80 is used to discriminate between demented and normal subjects). On the Mini-Mental State, their mean score was 16.7 (SD=5.7), and their mean decline in scores from baseline to diagnosis was 9.5 (SD=5.5).

Of the 1,609 persons who were not available for interview (42.6% of 3,778), 551 had died, 256 were too ill to participate, 607 were unwilling to participate, and 195 could not be contacted.

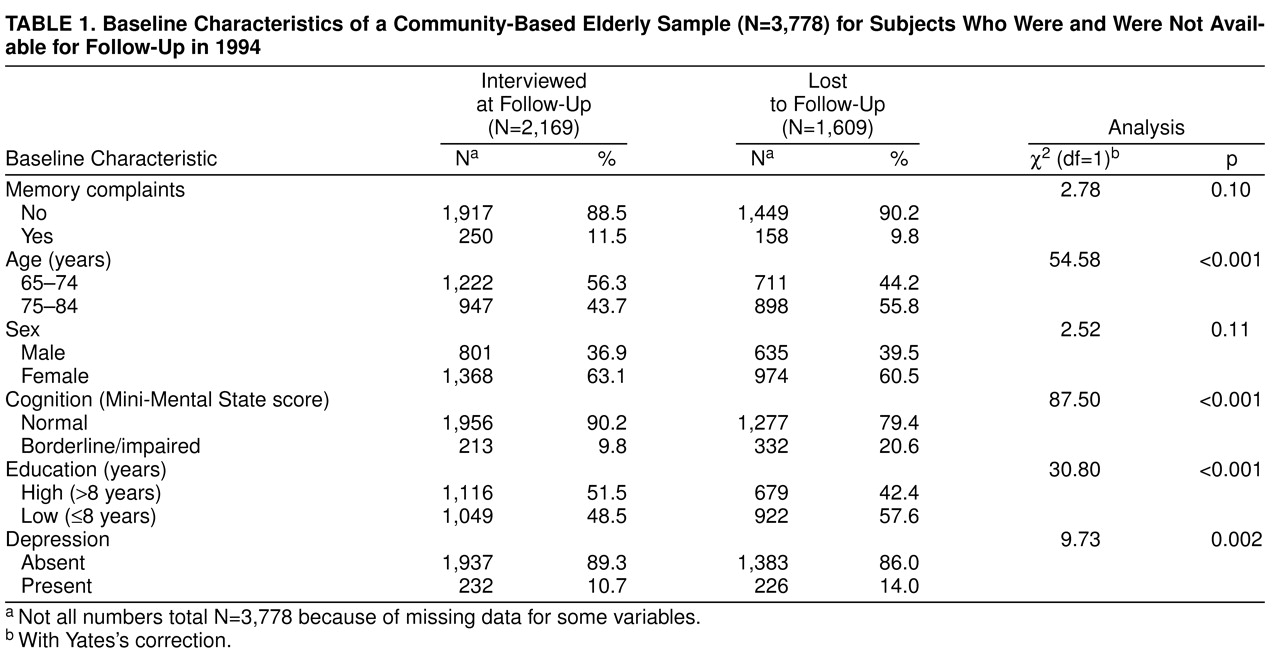

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of subjects who were available for interview and who were lost to follow-up. Subjects who presented memory complaints at baseline were not more likely to be lost to follow-up. In addition, there was no difference in sex between those who were and were not available at follow-up. However, older subjects, subjects with borderline and impaired cognition, subjects with a low level of education, and depressed subjects were more likely to be lost to follow-up. Of the 166 persons (38.3% of 433) who were not available for diagnostic evaluation, 71 had died in the period between the follow-up interview and the diagnostic evaluation, 34 were too ill to undergo diagnostic evaluation, 43 were unwilling to participate, and 18 could not be contacted.

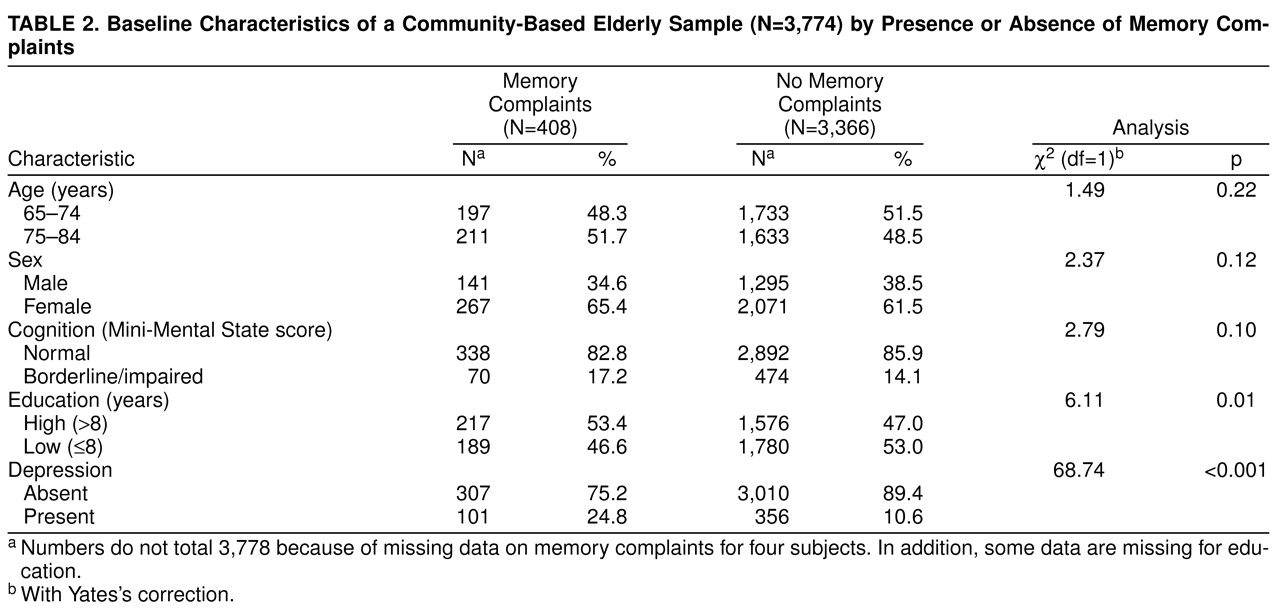

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the study sample, according to the presence or absence of memory complaints. As can be seen, 408 persons (10.8% of the sample) expressed complaints about their memory, and those who complained about their memory more often had higher levels of education and were more likely to be depressed. They did not differ from those without memory complaints with respect to age, sex, and cognition.

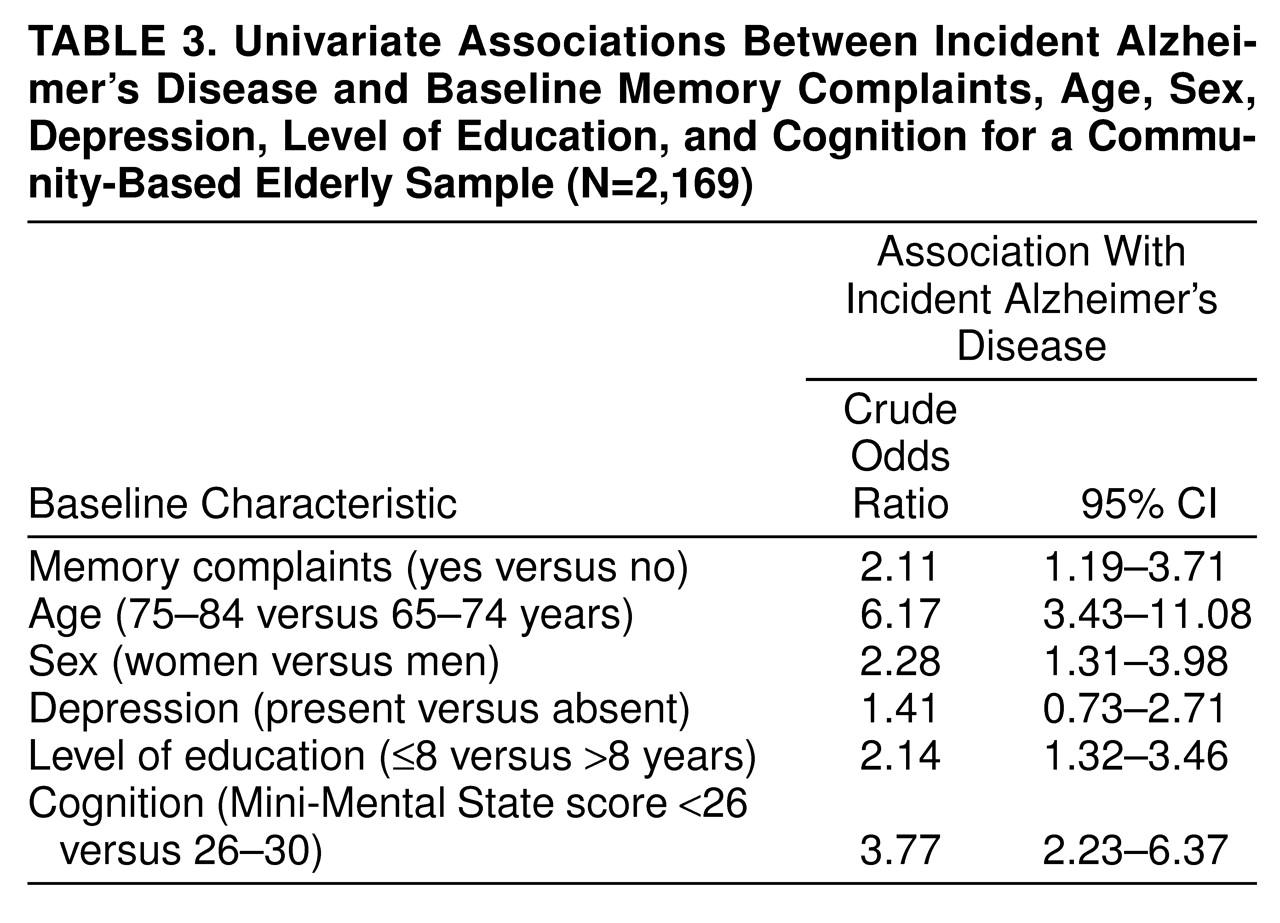

Table 3 shows the univariate associations between incident Alzheimer’s disease and memory complaints, age, sex, depression, level of education, and cognition, respectively. Memory complaints were associated with incident Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, higher age, female sex, low level of education, and impaired cognition were univariately associated with incident Alzheimer’s disease. In a multivariate regression analysis, with adjustments for age, sex, depression, level of education, and cognition, memory complaints were still associated with incident Alzheimer’s disease (odds ratio=1.95; 95% CI=1.07–3.53; not shown in

table 3 ). When subsequently the interaction between memory complaints and cognition was included in the multivariate model with adjustments for age, sex, depression, level of education, and cognition, the association between memory complaints and incident Alzheimer’s disease was found to be modified by cognition (likelihood ratio χ

2=5.79, df=1, p=0.02).

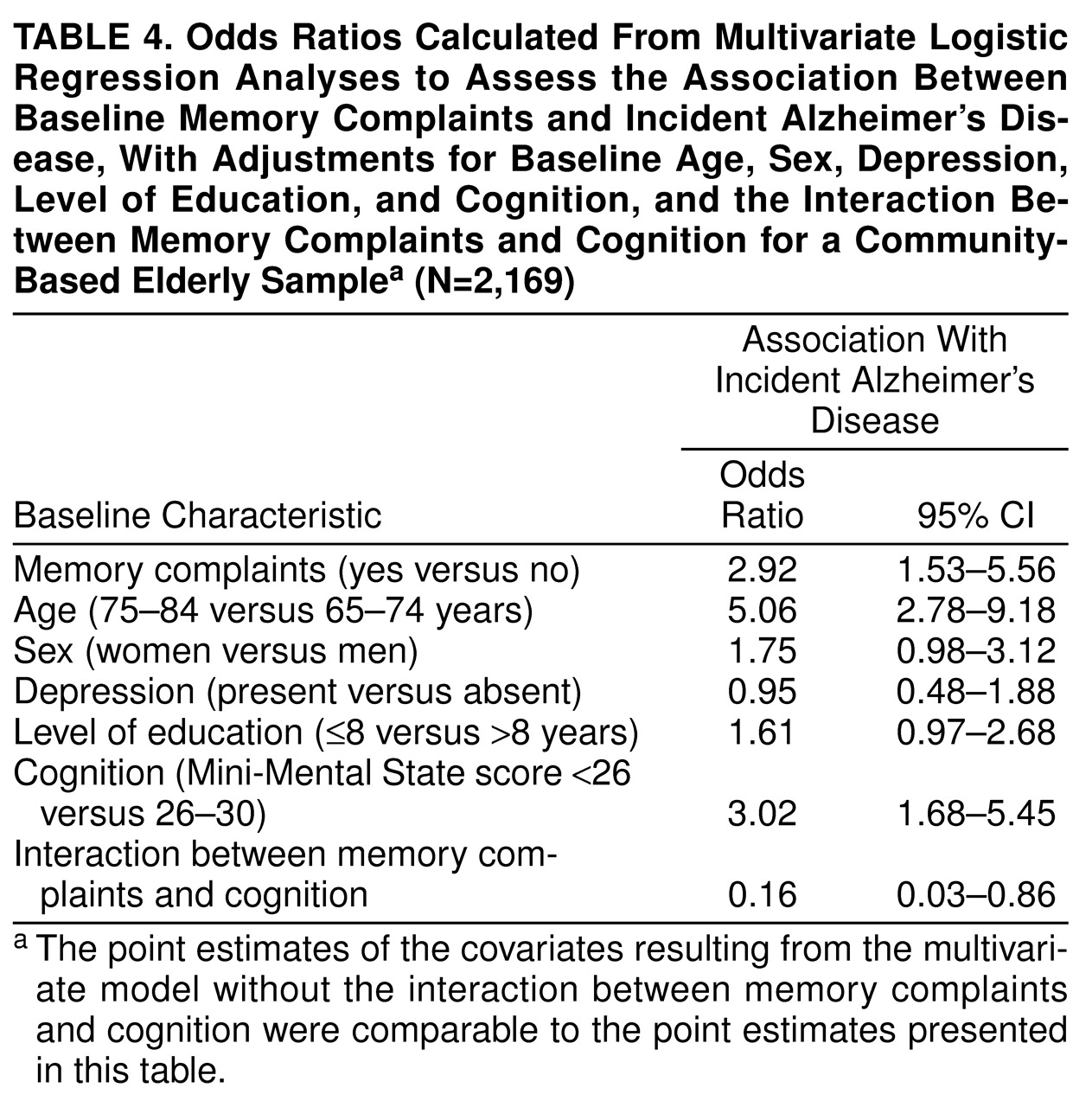

Table 4 shows the odds ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals calculated from the multivariate logistic regression analyses, including the interaction between memory complaints and cognition. There were no significant interactions between memory complaints and level of education or depression.

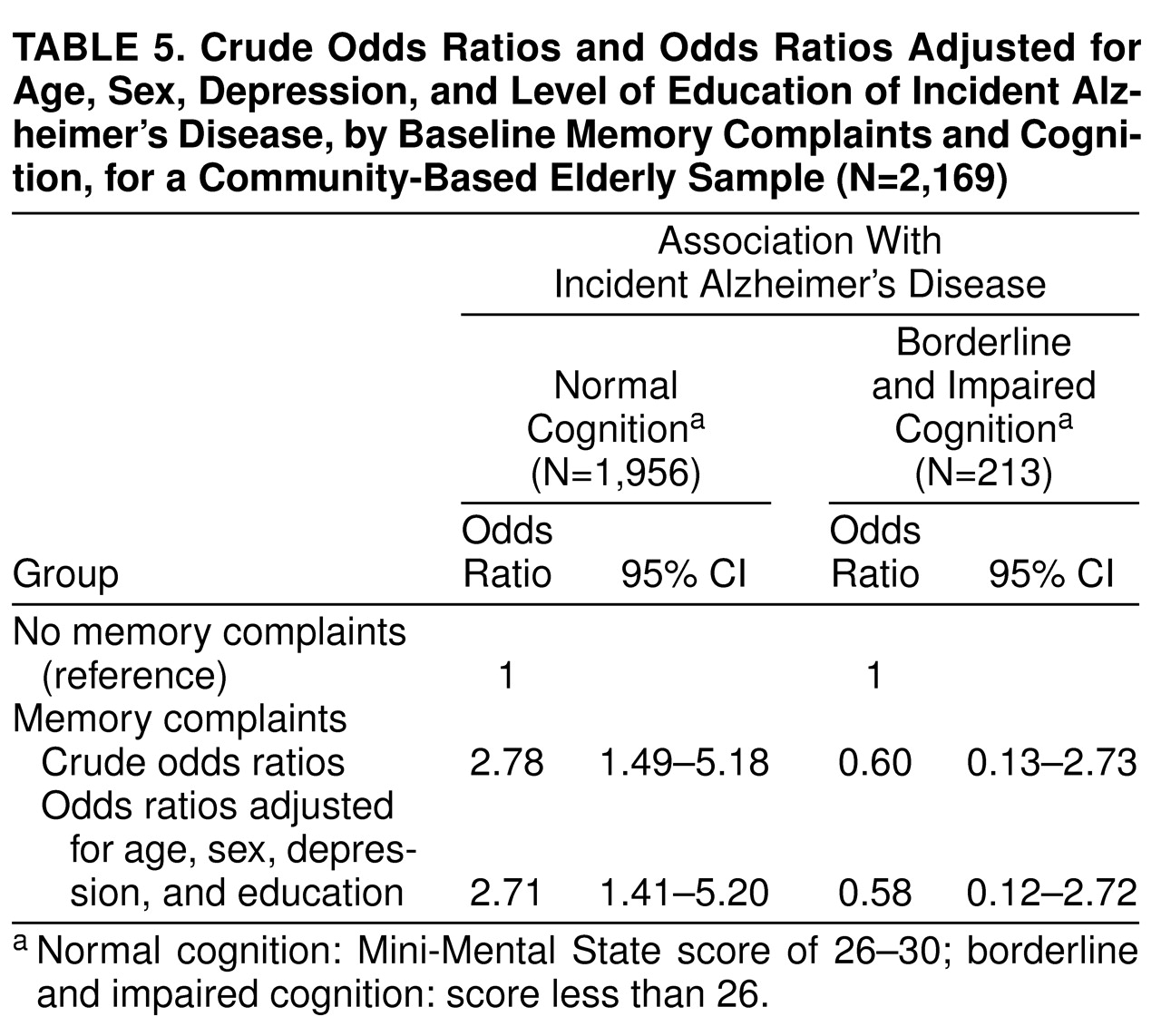

To examine the modifying relationship between memory complaints and cognition, separate logistic regression analyses were performed within each cognitive category. First, a univariate logistic regression analysis was performed, which showed that memory complaints were associated with incident Alzheimer’s disease among elderly people with normal cognition but not among those with borderline and impaired cognition. Second, within each cognitive category, adjustments were made for age, sex, depression, and level of education. These analyses showed that memory complaints were still associated with incident Alzheimer’s disease among elderly people with normal cognition; however, no association was found among those with borderline and impaired cognition (

table 5 ). There was no significant interaction between memory complaints and level of education or depression in either stratum.

DISCUSSION

In this study, a greater risk for Alzheimer’s disease associated with memory complaints was observed in elderly individuals with normal baseline cognition. Contrary to the procedure in two previous studies from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly, which involved the use of a memory scale based on a series of questions about memory complaints and memory-related problems (e.g., “Do you often forget where you left things?”)

(14,

15), in the present study only one simple question was used to assess memory complaints (“Do you have complaints about your memory?”). It is striking that the answer to such a general question that does not refer to specific memory-related problems can predict incident Alzheimer’s disease in elderly individuals with normal baseline cognition. It is also interesting to note that all of our participants still lived at home at the time of the baseline interview, and it can beassumed that most of them had not sought clinical attention for their memory complaints. In the two earlier studies, in which Schmand et al.

(14,

15) found an association between memory complaints and incident dementia, no differentiation was made between nondemented subjects with normal cognition and those with impaired cognition. The present study is the first to report this association among elderly people with normal baseline cognition, and in this respect, our results differ from those of Schofield et al.

(16). Using a similar question to assess memory complaints, Schofield et al. found an association between memory complaints and cognitive decline only in subjects with impaired cognition, not in those with normal cognition. One of the major differences between these two studies, which might explain the contrasting results, was the follow-up duration. The follow-up in the present study was 3.2 years, on average, while the follow-up in the study by Schofield et al. was 1 year. This rather short interval between baseline and follow-up measurements could have made it less likely to find an association between memory complaints and cognitive decline or dementia among elderly individuals with normal baseline cognition.

In our study, no association was found between memory complaints and incident Alzheimer’s disease in subjects with borderline and impaired baseline cognition, although a higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease in these subjects was expected because of their cognitive status. The absence of an association could be explained by the high percentage of deaths and loss to follow-up in this group (60.9% in the group with borderline and impaired cognition and 39.5% in the group with normal cognition). As a result, it might have been more difficult to find an association between memory complaints and incident Alzheimer’s disease. This bias may have resulted in an underestimation of the association between memory complaints and incident Alzheimer’s disease in the group with borderline and impaired baseline cognition. In addition, there might have been insufficient statistical power to find an association because this group was relatively small to begin with, compared to the group with normal baseline cognition.

Thus, while in the study by Schofield et al. the relatively short follow-up may have made it less likely to find an association between memory complaints and dementia in subjects with normal cognition, in our study the high proportion of subjects with borderline and impaired cognition who were lost to follow-up may have made it less likely to find an association between memory complaints and Alzheimer’s disease in these subjects. The results of both studies taken together suggest that given sufficient follow-up duration and sufficient follow-up data for all levels of cognition, memory complaints may predict cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease in elderly people with and without impaired cognition.

The subjects with normal baseline cognition who expressed memory complaints and developed Alzheimer’s disease in this study might represent a subgroup of persons who are at high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. During a relatively short period of time, they declined from apparently normal cognition to dementia. It is possible that these people correctly perceived a deterioration in their memory or cognitive functioning that could not yet be validated by objective test performance. The Mini-Mental State that was used at baseline may not have been sensitive enough to detect this cognitive decline.

In summary, on the basis of data from this large population-based cohort study with an average follow-up period of 3.2 years, it was found that memory complaints were associated with an almost threefold increase in the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease in elderly individuals with normal baseline cognition. This association could not be attributed to depression. The findings suggest that elderly people may be aware of a decline in cognitive functioning at a time when mental status tests are still unable to detect a decline from premorbid functioning.