Dysthymic disorder, a chronic, low-grade depressive condition, has a high prevalence in both community and outpatient samples, with rates of 3%–6%

(1,

2) and 22%–36%

(3,

4), respectively. Major depressive episodes are a frequent complication, as almost all individuals with dysthymic disorder experience exacerbations that meet criteria for a major depressive episode, or “double depression”

(5), at some point in their lives

(6–

9). At any given point in the course of dysthymic disorder, the level of symptoms is typically mild. Over time, however, individuals with dysthymic disorder experience greater cumulative symptoms and more suicide attempts and hospitalizations than persons with episodic major depression

(6). In addition, the level of functional impairment in dysthymic disorder typically equals or exceeds that in major depressive disorder and increases further during superimposed major depressive disorder episodes

(10–

12).

Since dysthymic disorder is defined largely by its persistence, studies examining factors that predict the long-term course and outcome of the disorder are critical. However, the few studies have focused primarily on demographic and clinical variables, and most have examined relatively short follow-up periods (i.e., 30 months or less). In a 2-year follow-up of patients with double depression, Keller and colleagues

(13) found that age, marital status, number of previous major depressive disorder episodes, subtype of major depressive disorder episode, and duration and type of onset of major depressive disorder did not predict recovery from the preexisting dysthymic disorder. In a combined retrospective/prospective follow-up of depressive disorders in childhood, Kovacs and colleagues found that earlier age at onset

(14) and comorbid externalizing disorders

(15) predicted a longer duration of dysthymic disorder, while sex, superimposed major depressive disorder, and comorbid anxiety disorders failed to predict recovery

(14,

16,

17). In a previous report from this project

(18), we found that age, gender, educational attainment, history of major depressive disorder, age at onset of dysthymic disorder, and comorbid anxiety, substance use, and personality disorders did not predict recovery from dysthymic disorder or level of depressive symptoms at 30-month follow-up. However, depressive personality predicted level of depression even after baseline depressive symptoms were controlled

(19). Early adversity and family history of psychopathology were also associated with course and outcome

(20).

The present article extends our earlier reports by examining a longer follow-up period and a broader range of predictors. The follow-up period was increased to 5 years, exceeding the length of most previous studies of prognostic factors in dysthymic disorder. In addition, we hypothesized that the course of dysthymic disorder is influenced by several factors, including distal variables such as familial psychopathology and early adversity, clinical variables such as comorbid axis I psychopathology and personality traits and disorders, and proximal socioenvironmental factors such as chronic stress and social support. Hence, we explored the prognostic utility of a multifactorial model and examined whether each domain would contribute to predicting the outcome of dysthymic disorder. We were particularly interested in determining whether the variables that best distinguished patients with dysthymic disorder from those with episodic major depressive disorder—family history of dysthymic disorder, early adversity, and personality disorders

(21–

23)—would also be associated with a more chronic course of dysthymic disorder.

Results

The patients were predominantly white (91.9%, N=79) and female (75.6%, N=65). Their mean age was 32.1 years (SD=9.7). Marital status was as follows: 46.5% (N=40) had never married, 31.4% (N=27) were married, 19.8% (N=17) were separated or divorced, and 2.3% (N=2) were widowed. The patients’ mean score on the Hollingshead’s Four-Factor Index of Social Status

(37) was in the mid-range of social class III (mean=34.6, SD=13.6). The subjects were moderately depressed at baseline, with a mean 24-item Hamilton depression scale score of 25.7 (SD=10.4). At 5-year follow-up, the recovery rate from dysthymic disorder was 52.3% (N=45)

(6).

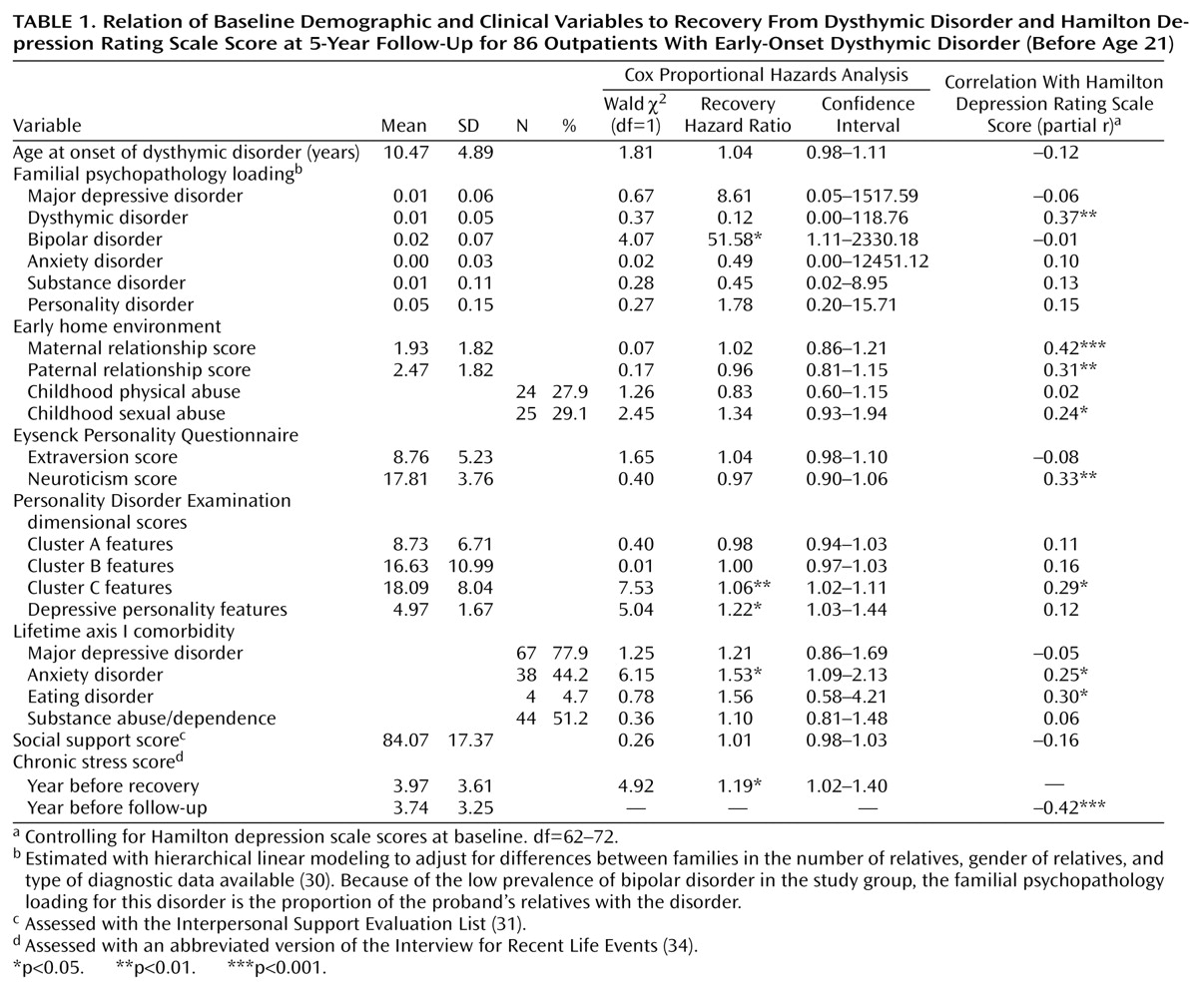

None of the descriptive characteristics predicted recovery or Hamilton depression scale scores at 5-year follow-up. Neither a superimposed major depressive disorder episode at baseline nor lifetime history of major depressive disorder was associated with recovery or level of symptoms at follow-up. A history of anxiety disorder, cluster C and depressive personality features, and chronic stress were significantly associated with lower recovery rates (

Table 1). In contrast, a family history of bipolar disorder was significantly associated with a higher probability of recovery. After baseline Hamilton depression scale scores were controlled, higher Hamilton depression scale scores at follow-up were predicted by a greater familial loading of dysthymic disorder, poorer maternal and paternal relationships, childhood sexual abuse, history of anxiety disorder and eating disorder, cluster C personality disorder features, higher Eysenck Personality Questionnaire neuroticism scores, and higher levels of chronic stress in the 12 months before follow-up.

Blocks of significant univariate predictors were used to construct a hierarchical Cox proportional hazards model predicting recovery. The order of entry was based on the likely chronological sequence of the impact of each domain: family history of bipolar disorder, cluster C and depressive personality features, comorbid anxiety disorder, and chronic stress in the year before recovery. Family history of bipolar disorder significantly predicted recovery from dysthymic disorder (χ2=4.07, df=1, N=86, p=0.04). Adding cluster C and depressive personality features to the model resulted in a significant change (change in χ2=7.71, df=1, N=86, p=0.02). Comorbid anxiety improved the model further (change in χ2=4.17, df=1, N=86, p=0.04). Finally, chronic stress also contributed a significant increment (change in χ2=4.69, df=1, N=72, p=0.03).

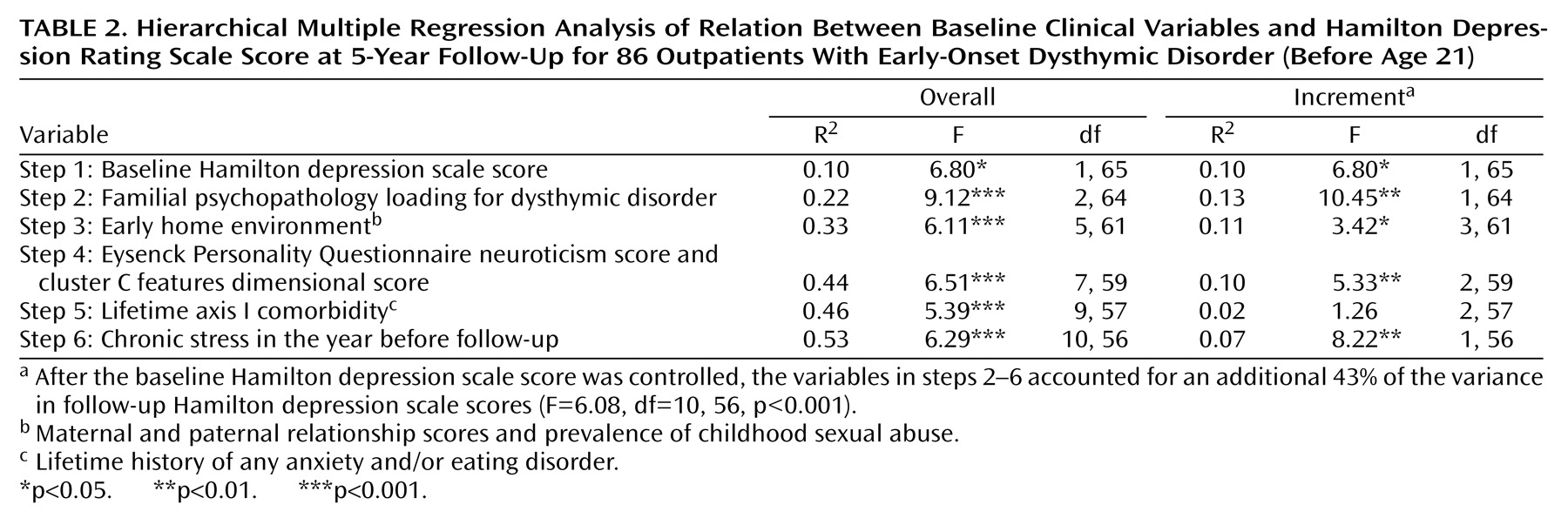

Similarly, we used blocks of the significant univariate predictors from each domain to construct a hierarchical multiple linear regression model predicting Hamilton depression scale scores at follow-up. Baseline Hamilton depression scale scores were entered first, followed by family history of dysthymic disorder, early adversity (early maternal and paternal relationships, childhood sexual abuse), personality (neuroticism and cluster C features), comorbid axis I psychopathology (anxiety and eating disorders), and chronic stress in the year before follow-up, in that order. As

Table 2 shows, after the baseline Hamilton depression scale score was controlled, the group of prognostic indicators accounted for an additional 43% of the variance in follow-up Hamilton depression scale scores (F=6.08, df=10, 56, p<0.001). Each block of predictors added a significant increment to the preceding blocks, with the exception of axis I comorbidity.

Discussion

We examined predictors of recovery and depressive symptoms in a 5-year follow-up of outpatients with early-onset dysthymic disorder and found that the domains of familial psychopathology, early adversity, axis I comorbidity, personality, and socioenvironmental factors were all associated with outcome. After the analysis controlled for baseline depressive symptoms, predictors entered in chronological order of their presumed effects accounted for an impressive 43% of the variance in the level of depression at 5-year follow-up. Previous studies, including our own 30-month follow-up of this group of subjects, have been less successful in identifying predictors of the course of dysthymic disorder

(13–

20). However, these studies have generally examined a limited number of predictors and followed patients for shorter periods of time. The difference suggests that more comprehensive models and longer durations of follow-up are necessary to identify prognostic factors in dysthymic disorder.

Comorbid anxiety disorder, depressive personality features, cluster C traits, and chronic stress were all associated with a lower probability of recovery from dysthymic disorder. In contrast, a family history of bipolar disorder was associated with a greater likelihood of recovery. Akiskal

(9) has suggested that some patients with dysthymic disorder may have bipolar spectrum conditions. If family history of bipolar disorder is a marker for this subgroup, it is not surprising that these patients experience a more cyclic, episodic course with a faster rate of recovery. However, given that family history of bipolar disorder had a low base rate in the study group and the confidence interval was large, this finding should be taken with caution.

Higher levels of depression at follow-up were predicted by a greater familial loading for dysthymic disorder, poorer maternal and paternal relationships, childhood sexual abuse, increased neuroticism and cluster C features, a history of anxiety and eating disorders, and a higher level of chronic stress in the previous 12 months. These results are consistent with our previous findings indicating that, at baseline, the variables that best distinguished patients with dysthymic disorder from those with episodic major depressive disorder were rates of dysthymic disorder in relatives, early adversity, and axis II comorbidity

(21–

23). Thus, it appears that the same variables that distinguish dysthymic disorder from episodic major depressive disorder are also among the best predictors of a poor course and outcome for patients with dysthymic disorder.

Chronic stress was one of the strongest predictors of both failure to recover and depressive symptoms at 5-year follow-up. Although the results are not presented here, we conducted further analyses examining the temporal relationship between chronic stress and recovery from dysthymic disorder. Patients who recovered had lower levels of chronic stress throughout the entire follow-up period, rather than a reduction in stress at a particular point before recovery. This pattern suggests that chronic stress is a relatively stable attribute of poor-outcome patients. High levels of chronic stress may, in part, be due to other poor prognostic factors such as early adversity, personality disturbance, and comorbidity

(38). For example, in this study group, there were low, but significant, correlations between the quality of the maternal relationship (r=0.22, df=77, p<0.02), childhood sexual abuse (r=0.25, df=77, p<0.01), cluster C dimensional scores (r=0.23, df=77, p<0.02), and lifetime anxiety disorder (r=0.22, df=77, p=0.03) assessed at baseline and the level of chronic stress in the year before follow-up. These data suggest the need for a more detailed examination of the complex links between early adversity, comorbidity, chronic stress, and the course of dysthymic disorder.

We have reported elsewhere that acute stressors may precipitate superimposed major depressive disorder episodes in the course of dysthymic disorder

(39). As acute stress is more likely to contribute to relapse than to maintenance of depression, we did not examine the role of acute stressors in recovery and symptoms at follow-up. However, other authors have proposed that positive, neutralizing, or “fresh-start” events play an important role in recovery

(40). Although we did not assess these events, they may be worth examining in future studies of the course of dysthymic disorder.

Fewer variables predicted recovery than predicted Hamilton depression scale scores in this study, perhaps because recovery is a heterogeneous outcome in dysthymic disorder, with some patients experiencing a sustained recovery and others having a relatively brief recovery in the context of a generally chronic course

(6). Combining these subgroups may obscure important predictors. We did not analyze predictors of relapse in this article, owing to the relatively small number of patients who had recovered and relapsed at this point in the follow-up.

Our study group was representative of patients with dysthymic disorder in most clinical settings in that many patients had a superimposed major depressive disorder episode and others had a past history of major depressive disorder. Although we cannot be certain that our findings would generalize to “pure” dysthymic disorder patients, we have found few differences between patients with double depression and those with dysthymic disorder alone in familial psychopathology, early adversity, and comorbidity

(21–

23). Moreover, in the present report, superimposed major depressive disorder episodes (current and lifetime) did not predict recovery from dysthymic disorder or Hamilton depression scale scores at follow-up.

The strengths of our study include its prospective design, relatively lengthy follow-up period, and use of an extensive assessment battery, semistructured interviews, and blind follow-up evaluations. However, the study also has several limitations. We conducted a large number of statistical tests without adjusting significance levels, raising the possibility that some findings might be due to chance. Our study group was modest in size, limiting our power to detect small effects. Many of our family history variables had low base rates and large confidence intervals, suggesting that these analyses should be taken cautiously. Relative to the instances of recovery, the number of predictors examined was large. Patients were asked to report about relatively lengthy follow-up intervals. Finally, the size of the significant effects was moderate; hence, their clinical utility may be limited. Nonetheless, our findings suggest the value of conceptualizing the course and outcome of dysthymic disorder within a multifactorial framework, with family history of psychopathology, early adversity, personality, axis I comorbidity, and chronic stress all making important contributions.