Duration of untreated psychosis is generally long in schizophrenia (the mean is more than 1 year)

(1,

2) and has been associated with variability in treatment response

(3). Although several studies have examined the relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and general treatment response, individual symptoms have not been studied. Further, there is limited information regarding the time course of resolution of specific psychotic symptoms with antipsychotic treatment

(4).

The first-episode schizophrenia studies conducted at Hillside Hospital, Glen Oaks, N.Y., have provided us with a unique opportunity to follow patients for up to 5 years, starting from early stages of their illness, and make clinical observations that would have been impossible to do in short-term trials

(5,

6). One of these observations is that patients with relatively long duration of untreated psychosis seem to take longer to give up their delusional beliefs than to recover from other symptoms such as hallucinations. It is widely accepted that delusions take longer to resolve than hallucinations. In the current study we also studied the response patterns of individual psychotic symptoms in relation to duration of untreated psychosis because such a differential association may be informative for clinical practice.

Our aim was to examine the relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and time to treatment response for delusions and hallucinations. We hypothesized that time to response for delusions would be longer than that for hallucinations. We also hypothesized that duration of untreated psychosis would be correlated with time to response for delusions but not for hallucinations. Additionally, we examined whether duration of untreated psychosis would predict time to response for both psychotic symptoms.

Method

The general methods of the study have been described in detail elsewhere

(5,

6). Briefly, patients at Hillside Hospital who were experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia were recruited according to guidelines of the Long Island Jewish Hospital Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from patients and, if possible, from their families. Psychopathology was assessed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Change Version with psychosis and disorganization items (SADS-C)

(7) and the Clinical Global Impression. Patients were treated according to a medication algorithm under open conditions for up to 5 years.

For this retrospective analysis, patients were included who had severity ratings for hallucinations or delusions of 2 (suspected or likely) or higher (definite) on the SADS-C at baseline. Treatment response was defined as a severity rating for hallucinations or delusions of 1 (absence) on the SADS-C for 6 weeks. Severity of hallucinations and severity of delusions were measured by the mean of the ratings for the severity of these symptoms.

Duration of untreated psychosis was assessed by interviews with patients and families. Duration of untreated psychosis was skewed and was dichotomized at 52 weeks. Highest level of functioning was measured by using the Premorbid Adjustment Scale

(8). Parkinsonism was assessed by using the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale

(9).

The hypothesis that delusions would take longer to resolve was assessed with a Wilcoxon signed-ranks test. Correlations were carried out for duration of untreated psychosis and treatment response time for the target symptoms. Prediction of time to response was assessed with regression analyses. The significance level was p<0.05, two-tailed. Analyses were performed with SAS Version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

Results

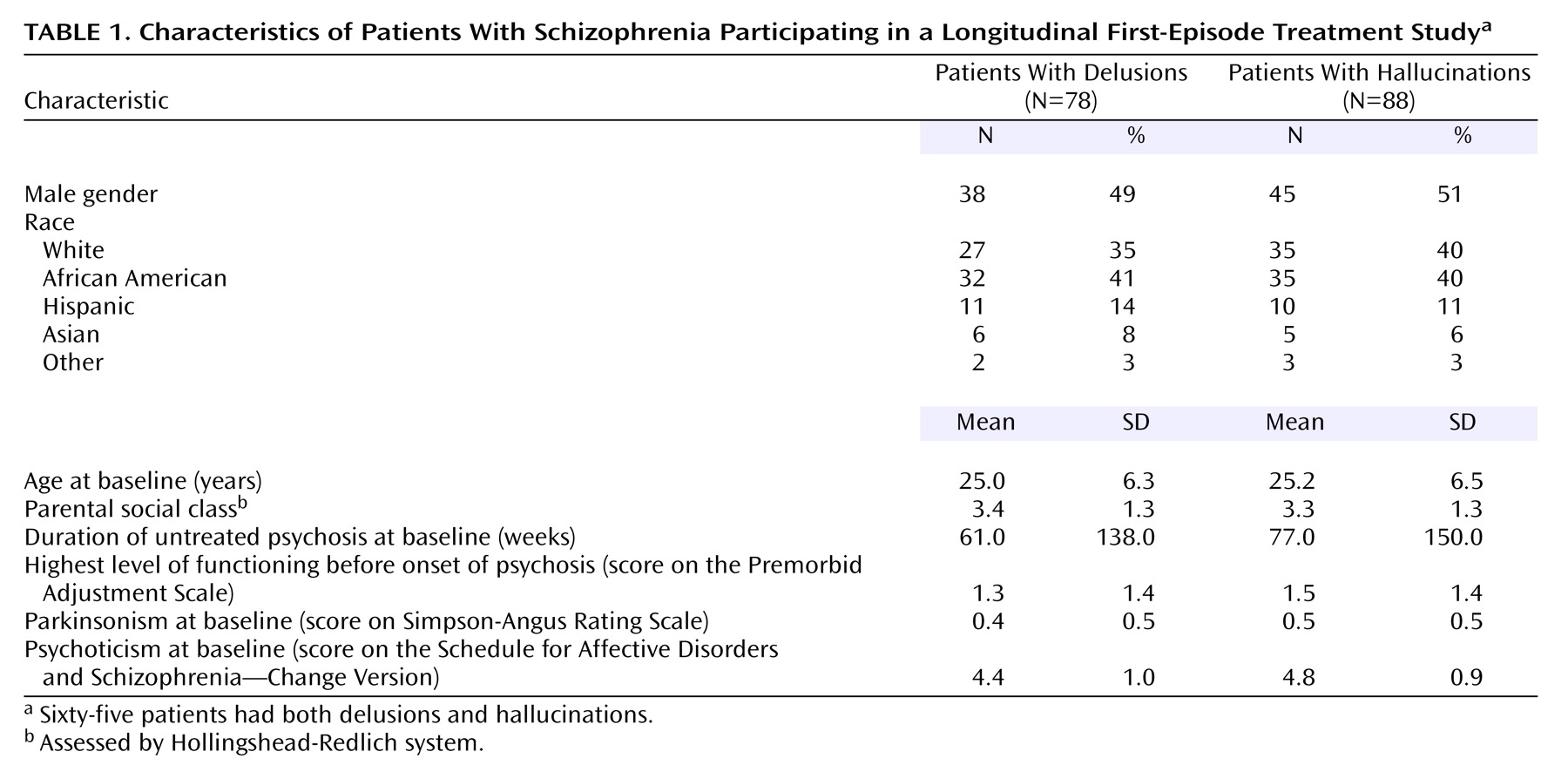

Seventy-eight subjects had delusions at baseline and met response criteria for delusions. Eighty-eight subjects had hallucinations at baseline and met response criteria for hallucinations. Sixty-five subjects met criteria for both symptoms. The characteristics of the two groups are presented in

Table 1.

The number of days to response for delusions (median=76; mean=150, SD=239) was significantly greater than that for hallucinations (median=27; mean=59, SD=104) (T=5308, p<0.0001, Wilcoxon signed-ranks test). For delusions, the rank biserial correlation for duration of untreated psychosis and time to treatment response was r=0.39, N=78, p<0.02, while for hallucinations it was r=0.17, N=88, p=0.23.

The regression analyses were based on univariate correlational analyses (p<0.10) and previous publications on the same group of patients

(6). Independent variables predicting time to response for delusions were duration of untreated psychosis, gender, parental social class, highest level of functioning, baseline parkinsonism, and baseline severity of delusions. Since time to response was skewed, a log transformation was used. Stepwise regression analyses indicated that duration of untreated psychosis was the only significant predictor for time to response for delusions (F=8.03, df=1, 69, p=0.006, R

2=0.10). Parental social class (F=4.5, df=1, 76, p<0.04) and baseline severity of hallucinations (F=7.99, df=1, 76, p=0.006) were significant predictors for time to response for hallucinations (F=6.05, df=2, 76, p=0.004, R

2=0.14). The results were unchanged when either forward or backward stepwise procedures were used.

We carried out the same analysis for a subset of patients who met entry criteria for both delusions and hallucinations at baseline (N=65). For time to response for delusions for these patients, duration of untreated psychosis was the only predictor (F=8.21, df=1, 56, p<0.006, R2=0.13). For time to response for hallucinations, baseline severity of hallucinations was the only predictor (F=4.83, df=1, 56, p<0.04, R2=0.08).

Discussion

These results confirm the clinical impression that time to response for delusions is longer than time to response for hallucinations. Duration of untreated psychosis may be specifically related to time to response for delusions but not for hallucinations. Delusions reflect thought patterns, whereas hallucinations are abnormal perceptual experiences. Roberts

(10), by integrating previous theories, proposed that, like the formation of normal belief, delusional belief may also follow a temporal sequence. This sequence may progress through stages, including a prepsychotic stage that harbors predisposing and precipitating factors, an acute stage characterized by anomalous experiences and attribution of meaning to experience (formation of simple delusions), and a chronic stage, where a fixed delusional system is formed. It has been suggested that the environment contributes to persistence of simple delusional beliefs and emergence of fixed delusions “by suspicious withdrawal, fostering a process of progressive exclusion and depriving the patient of corrective experiences”

(11). In contrast, theories of formation of hallucinations include biological phenomena such as cortical disinhibition and excitability

(12). Therefore, delusions and hallucinations may have different vulnerabilities to the effects of time, i.e., untreated psychosis may reinforce abnormal thought patterns over time as opposed to perceptual abnormalities, which may be spared this temporal relationship.

Our finding may implicate different neural mechanisms underlying delusions and hallucinations even though both symptoms are frequently reported simultaneously when schizophrenia is first diagnosed. Several studies

(13–

18) showed that smaller superior temporal gyrus volume is selectively correlated with severity of auditory hallucinations. Correlations between delusions and structural imaging data are more scarce; larger paleocortical relative to archicortical volumes have been associated with severity of delusions

(19). Parahippocampal gyrus volumes were found to be negatively correlated with delusions, but not hallucinations

(20), supporting findings of the former report

(19). Symptom clusters have not been systematically investigated in functional and receptor imaging studies. Although the association of delusions and hallucinations with possible distinct neuroanatomic regions needs to be further explored in relation to duration of untreated psychosis, there is support for different neural substrates for the two symptoms.

An association between baseline severity of symptoms and global treatment outcome has been reported

(21). The fact that severity of baseline hallucinations was a predictor for time to response for hallucinations but the severity of baseline delusions and time to response for delusions were not associated provides further support for presence of distinct correlates for the two symptoms. Parental social class was another predictor of time to response for hallucinations (standardized beta weight=–0.23); higher parental social class correlated with longer time to response for hallucinations.

Replication of the results of this investigation in independent samples may indicate a need to revisit the current clinical practice in the pharmacological treatment of first-episode schizophrenia. Specifically, for a patient with relatively long duration of untreated psychosis, response for delusions may be delayed despite successful treatment as reflected by attenuation of hallucinations. Patients with a short duration of untreated psychosis would be expected not to have this disadvantage. To further test this hypothesis, there is a need for controlled clinical trials in which the dose needed for subjects’ hallucinations to abate would be either maintained or titrated up in order to compare improvement in delusions in these two arms.

Important constraints in this retrospective analysis exist, such as lack of further characterization of duration of untreated psychosis. Duration of untreated psychosis itself may be dominated by delusions, hallucinations, or disorganization. This level of detail in the duration of untreated psychosis history was not available in our records. Future prospective studies are needed to clarify these matters.