Suicide is a major public health concern in most Western countries. Unfortunately, current prevention strategies are based on screening for numerous risk factors, none of which has been shown to have sufficient predictive power

(1). A stress-diathesis model was recently constructed

(2) to model and expand knowledge concerning the pathophysiology of suicidal behavior. According to this model, only persons with a susceptibility (diathesis) to suicidal behavior are at risk of attempting to take their own lives after exposure to stress.

Many studies have provided evidence that the serotonergic system is involved in this susceptibility. Indeed, several studies of suicide attempters or completers have identified specific serotonergic impairments, predominantly in the orbitofrontal cortex and the brainstem (for review, see reference

3). Thus, alterations in the activity of the serotonergic projections to the orbitofrontal cortex appear to be an important component of susceptibility to suicidal behavior. Furthermore, molecular genetic studies have reported associations of suicidal behavior with serotonin-related genes

(4–

6). Nonreplication

(7) may be accounted for by the heterogeneity and multiple causes of suicidal behavior. Neuropsychological traits could be used to increase the homogeneity of suicidal behavior groups in studies.

A few studies have investigated neuropsychological dysfunction in suicide attempters. Keilp et al.

(8) found that depressed suicide attempters presented a deficit in executive functions, which are known to be linked to the prefrontal cortex, independently of the severity of depression. The cognitive function of decision making has been shown to be linked to the orbitofrontal cortex by lesion

(9–

11) and functional imaging studies

(12–

15). Damage to the orbitofrontal cortex leads to high-risk, disadvantageous decisions in real life

(16,

17). If a lesion is restricted to the orbitofrontal cortex, all classic neuropsychological test results are normal, except those assessing decision making, such as the Iowa Gambling Task

(18) and others

(10). Moreover, previous studies reported the possible modulation of decision-making functions by the serotonergic system

(10,

19).

Assuming that the orbitofrontal cortex and the serotonergic system are involved both in this cognitive function and in susceptibility to suicidal behavior, we tested the hypothesis that decision making is impaired in suicide attempters. We also investigated whether Iowa Gambling Task performance was correlated with personality traits that are thought to be linked to the prefrontal cortex, suicidal behavior, and serotonergic dysfunction.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Variables

The four groups (healthy comparison subjects, affective control subjects, nonviolent suicide attempters, and violent suicide attempters) were statistically similar in terms of age, level of education, and National Adult Reading Test score (

Table 1). They differed significantly in terms of sex ratio, with fewer women among the healthy comparison subjects and the violent suicide attempters (26.8% and 34.4%, respectively) than among the affective control subjects and the nonviolent suicide attempters (64.0% and 67.6%, respectively) (p=3.10

–5).

The two groups of suicide attempters did not differ in terms of the number of previous suicide attempts and the age at first suicide attempt. Violent suicide attempters had a higher mean risk score (Risk Rescue Rating Scale) than the nonviolent suicide attempters (11.1 versus 8.7) (p=0.01).

For axis I disorders, only substance abuse differed between the groups since it was more frequent in the violent and nonviolent suicide attempters than in the affective control subjects (36.7%, 33.3%, and 4.0%, respectively) (p=6.10–3). The three groups of patients differed in terms of medication use on examination: violent and nonviolent suicide attempters were more likely than the affective control subjects to be taking benzodiazepines (41.9%, 67.6%, and 4.0%, respectively) (p=10–6). The proportion of patients not taking medication and using antidepressants was similar in all three patient groups.

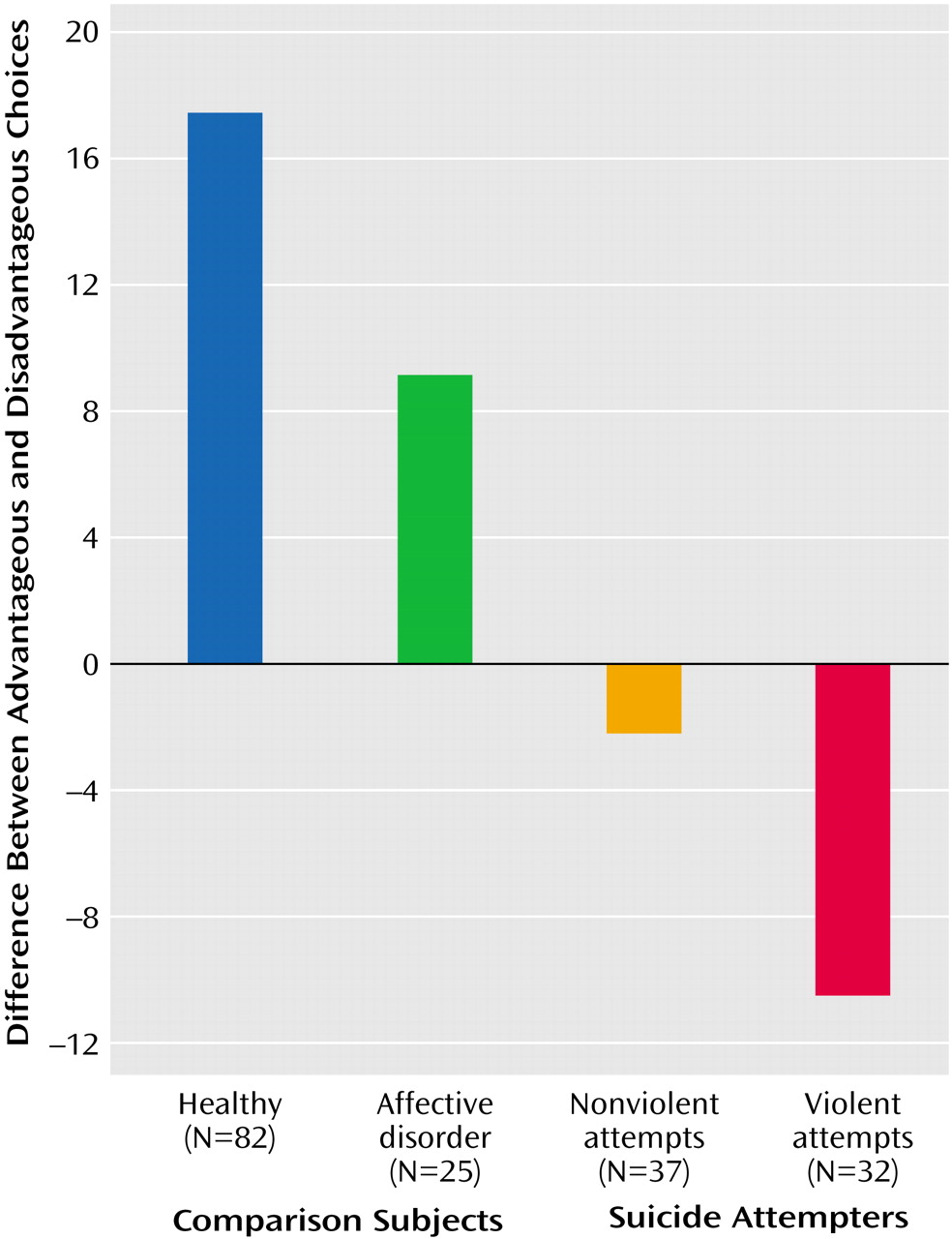

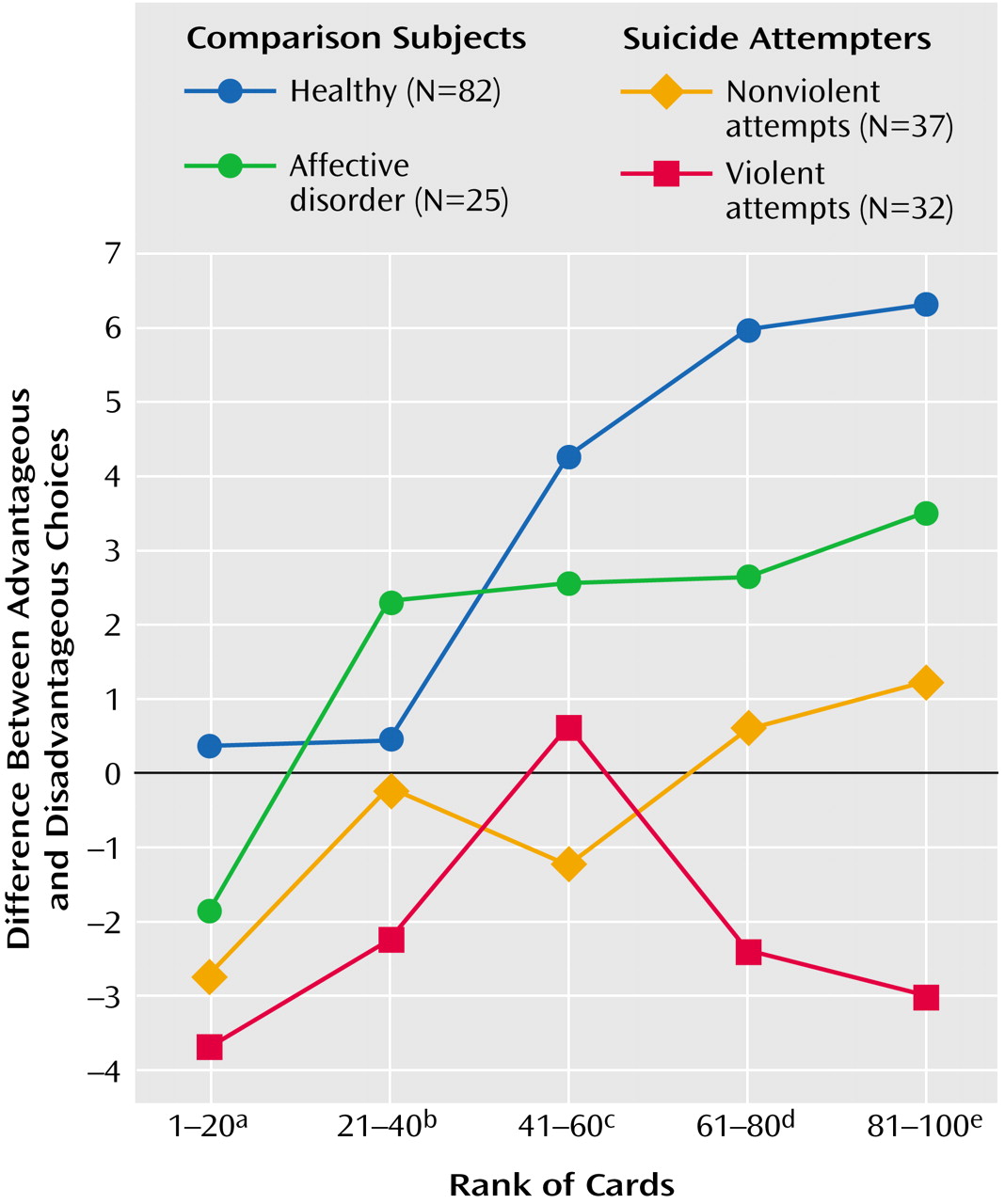

Iowa Gambling Task Performance

Within each group, intermediate scores significantly changed during the course of the test for the healthy comparison subjects (Friedman’s test=50.9, df=4, p<10

–5), the nonviolent suicide attempters (Friedman’s test=8.1, df=4, p=0.05), and the violent suicide attempters (Friedman’s test=11.6, df=4, p=0.04) but not for the affective control subjects (Friedman’s test=4.6, df=4, p=0.30) (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Table 1).

Comparison of scores among the four groups showed that for the fifth score (p=5.10–5) and the net score (p<10–5), the healthy comparison subjects differed significantly from both groups of suicide attempters, and the violent suicide attempters differed significantly from the affective control subjects. In contrast, no significant differences were observed between the nonviolent and violent attempters, between the healthy comparison and affective control subjects, and between the nonviolent suicide attempters and the affective control subjects.

The net score for the Iowa Gambling Task did not differ significantly according to sex when we considered the entire population and within each of the four groups of subjects. There was no difference according to a history of psychiatric disorders when we considered the three patients groups as a whole. Concerning the particular case of substance abuse disorders, we compared all suicide attempters with and without a substance abuse disorder, and we found no significant difference for the mean net scores. Moreover, after removing all of the substance abusers, comparisons of the net scores among the four groups (violent suicide attempters, nonviolent suicide attempters, affective control subjects, and healthy comparison subjects) yielded no qualitative change compared to what was found previously when we did not exclude the substance abusers. Thus, we think that our results may reasonably be linked to suicidal behavior and not to substance abuse.

Furthermore, the net score for the Iowa Gambling Task was not significantly correlated with age, level of education, National Adult Reading Test score, age at first suicide attempt, the number of previous suicide attempts, or the various scores for the Suicidal Intent Scale and the Risk Rescue Rating Scale. Finally, the net scores were not statistically different within each group between centers.

To exclude the effect of medication, we compared all patients with (N=79) and without (N=15) any medication and found that their performances were similar. In our groups, benzodiazepines were overrepresented in both groups of suicide attempters, and these drugs may have affected the attention of these patients. Therefore, we compared patients with (N=39) and without (N=55) benzodiazepines and found no significant difference in net score for the Iowa Gambling Task (Wilcoxon’s test=1709.5, df=1, p=0.30). Patients with (N=67) and without (N=26) antidepressants also performed similarly (Wilcoxon’s test=3007.5, df=1, p=0.20).

It is possible that minimal brain lesions resulting from the suicidal act may account for the differences in performance between groups. We investigated whether this was the case by comparing the Iowa Gambling Task performances of patients who had (N=24) and had not (N=61) experienced a coma or a head trauma (data missing for nine subjects) and found no significant difference between these two groups (Wilcoxon’s test=959.5, df=1, p=0.50). The distribution of these possible sources of brain lesions was similar in violent and nonviolent suicide attempters (39.1 and 40.5%) (χ2=0.01, df=1, p=1.00).

Psychometric Measures and Iowa Gambling Task Performance

We evaluated the correlations among all the scores of the various scales assessing personality dimensions and net score on the Iowa Gambling Task for violent suicide attempters, nonviolent suicide attempters, and all suicide attempters together. For all suicide attempters together, net score on the Gambling Task was significantly correlated with the bipolar score of the Affective Lability Scales (r=–0.32, p=0.05). For nonviolent suicide attempters, net score on the Iowa Gambling Task was significantly correlated with the anger-out score on the Spielberger State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (r=0.45, p=0.02) and the resentment score on the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (r=0.32, p=0.04). For violent suicide attempters, no correlation was significant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to report a specific impairment in decision making in suicide attempters. We found that violent and nonviolent suicide attempters achieved lower scores in a decision-making task, the Iowa Gambling Task, than did healthy comparison subjects. This impairment in decision making seems to be associated with susceptibility rather than with a state because all patients were evaluated during a period in which they did not have an axis I disorder. No difference was observed between healthy and affective control subjects, which is consistent with a previous study in euthymic bipolar patients

(33). In contrast, there was a significant difference between violent suicide attempters and affective control subjects, suggesting that the decision-making impairment identified was associated with susceptibility to suicidal behavior rather than susceptibility to affective disorders. Furthermore, psychiatric history had no effect on performance. It has to be outlined that in our group, a diagnosis of substance abuse disorder does not impair decision-making performance, although in a previous study, the two-thirds of substance abusers were impaired on the Iowa Gambling Task

(34). This raises the question of a common trait that would be shared by suicide attempters and substance abusers. Thus, in our groups of suicide attempters, susceptibility to psychiatric disorders did not seem to affect decision making as much as susceptibility to suicidal behavior did. Finally, we found no significant difference between the two groups of suicide attempters.

The Iowa Gambling Task has been shown to involve various cerebral regions, especially the orbitofrontal cortex and the amygdala

(26,

35). Our results seem to be consistent with a recent imaging study

(36) reporting an association between lower levels of ventromedial activity and both higher suicidal intent and higher lethality of the act. First, we observed that suicide attempters performed poorly on the Iowa Gambling Task. Violent, but not nonviolent, suicide attempters showed a gradual change in their pattern of choices during the Iowa Gambling Task that was very similar to that observed in patients with an orbitofrontal cortex lesion. Violent suicide attempters begin by sampling all decks until the 60th card, as do subjects from other groups; then they make more and more disadvantageous choices

(35). Second, the impairment was more marked in violent suicide attempters who also had a higher Risk Rescue Rating Scale risk score (i.e., a higher lethality). Thus, impaired decision making in suicide attempters may reflect an orbitofrontal cortex dysfunction. Functional imaging studies, with a decision-making paradigm, would be useful in identifying precise regional dysfunctions in suicide attempters.

Decision making has been found to be impaired in various psychiatric disorders involving discrete association of aggressive impulsivity, increased risk of suicidal behavior, and orbitofrontal cortex and/or serotonergic dysfunctions, such as substance abuse

(34,

37,

38), affective disorders

(33,

39), conduct disorder

(38), impulsive aggressive disorder

(40), and psychopathic

(41) and borderline personality disorders

(42). Moreover, both the orbitofrontal cortex and the serotonergic system have been linked to the control of impulse

(43,

44), and suicide attempters tend to be more impulsive

(2). In this study, we found no correlation between impulsivity (motor or cognitive), as measured by the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, and Iowa Gambling Task performance. This is consistent with the results of a recent study carried out in borderline patients

(42). As discussed by Bechara et al.

(35), the link between decision making and a specific component of impulsivity remains to be clarified. Furthermore, it has been suggested that questionnaire-based and laboratory-based assessments of impulsivity may differ

(45).

We found that in suicide attempters, Iowa Gambling Task performance was better as affective lability was higher. Furthermore, anger dyscontrol was positively correlated with the Iowa Gambling Task only in the subgroup of nonviolent suicide attempters. The orbitofrontal cortex is involved in the emotional processing thought to be necessary for normal decision making

(35). Thus, the decision-making deficit reported here may reflect a more global emotional dysfunction in some suicide attempters, even when they are not suffering from a current affective disorder. This also raises the question of the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior (violence, lethality) and of its link with different patterns of personality traits.

This study has several limitations. First, although the number of participants was large for a neuropsychological study, the size of the groups combined with the use of nonparametric tests—which are more robust but less sensitive than parametric tests—limited the statistical power of some comparisons. Replication in larger groups is required to validate these results.

Smoking status has not been taken into account in the present study. However, in a recent work published during the review process for this article, Rotheram-Fuller et al.

(46) reported an effect of smoking in methadone-maintained patients but not in comparison subjects. Thus, smoking status needs to be controlled in further studies.

Moreover, most of our patients were taking medication, and we found it difficult in this preliminary study to stop them. Therefore, we chose to compare the suicide attempters with a group of comparison subjects who were also taking medication. This affective control group did not differ significantly from the healthy comparison group, whereas the group of violent suicide attempters did. Furthermore, as shown in a previous study using different decision-making tests in medicated depressed and manic patients

(39), we found no effect of this variable on the performance of the Iowa Gambling Task.

It is also possible that minimal brain lesions resulting from the suicidal act may account for the differences in performance among groups. Again, comparison of performance between subjects with or without head trauma/coma yielded no difference. Nevertheless, there remains a small risk that subclinical brain damage may have biased certain results.

Finally, it remains necessary to investigate nondepressed suicide attempters by using other neuropsychological functions related to prefrontal activity, such as working memory, error monitoring, and conflict resolution.

In conclusion, we report here a decision-making defect in noncurrently depressed suicide attempters that may be correlated with emotional dysfunction. Decision-making impairment may therefore represent a vulnerability factor for suicidal behavior.