Circadian studies have found low peripheral basal cortisol concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), whereas results of single time-point plasma and urinary free cortisol studies have been variable

(1,

2). Given the elevation in CSF corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) in PTSD, even normal circulating cortisol levels could be considered low (3). Cortisol enters the brain readily from plasma, but levels in the CSF cannot be inferred directly from peripheral measures

(4–

7). CSF cortisol concentrations, however, have never been examined in PTSD. We used serial CSF sampling to extend the study of cortisol in PTSD into the CNS.

Method

Patients and Normal Volunteers

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Cincinnati Medical Center and the Research Committee of the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects.

We studied 16 medication-free subjects—eight healthy men and eight men with combat-related PTSD, interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. We excluded current or past psychiatric disorder or current substance abuse (except tobacco) in healthy volunteers and a history of these disorders in their first-degree relatives. The mean ages of the healthy volunteers and PTSD subjects were 41.3 years (SD=8.7) and 41.0 years (SD=10.4), respectively, and the mean body mass indexes of the volunteers and patients were 25.4 kg/m2 (SD=4.0) and 29.3 kg/m2 (SD=4.2), respectively. All PTSD subjects had been exposed to severe combat trauma, and all were free of current substance abuse (except tobacco) (data on file). The patients’ mean Clinician Administered PTSD Scale and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores were 81.9 (SD=23.2) and 12.6 (SD=4.3), respectively.

Subjects were admitted to the Clinical Research Unit the day before the CSF withdrawal procedure, according to a standard protocol (3, 8). A 20-gauge catheter was placed in the lumbar subarachnoid space at 8:00 a.m. the morning of the withdrawal, and continuous CSF withdrawal into iced test tubes was begun approximately 3 hours after catheter placement

(3,

8). Blood was withdrawn at intervals from a heparin lock.

CSF cortisol, plasma cortisol, and ACTH were assayed by radioimmunoassay (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Costa Mesa, Calif.). Hourly CSF cortisol samples were assayed, in duplicate, as described elsewhere (9). Respective intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation were 7.2% and 2.5% for cortisol and 11.0% and 6.0% for ACTH. Previous assays of urinary free cortisol and CSF CRH were reported

(3).

Repeated-measures analyses were conducted according to a linear mixed model where subjects, nested within subgroups, were treated as random effects while all other covariates (time, age, body mass index) were treated as fixed effects. Pearson correlation coefficients were used in all correlation analyses, and t tests were performed on means; p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

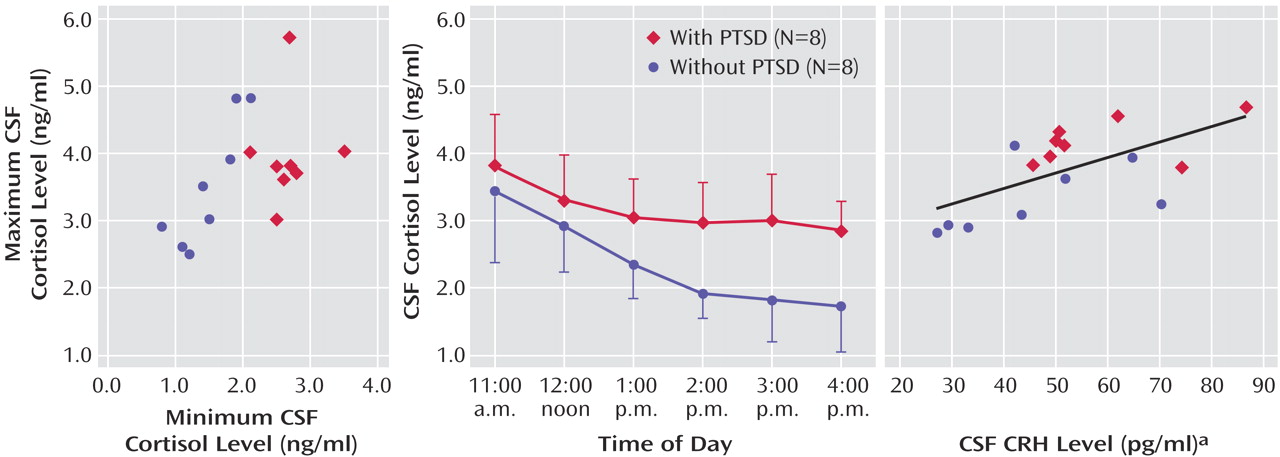

CSF cortisol concentrations were significantly higher in the patients with PTSD (mean=3.18 ng/ml, SD=0.33) than in the normal volunteers (mean=2.33 ng/ml, SD=0.50) (

Figure 1). Using repeated-measures analysis, we found a main effect for group (F=9.81, df=1, 12, p<0.01) but no significant group-by-time interaction. The coefficient of variation (standard deviation/mean) calculated for each study subject across the six time points was significantly lower for the patients with PTSD than for the healthy volunteers (F=15.37, df=1, 11, p<0.003). Additionally, a comparison of zenith versus nadir CSF cortisol concentrations over the collection period revealed a significant group (PTSD versus healthy) difference in CSF minimum cortisol levels (t=5.74, df=14, p<0.0001) but not in maximum cortisol levels (t=1.06, df=14, n.s.) (

Figure 1).

Mean plasma ACTH concentrations for the patients with PTSD and the normal volunteers were 108.49 pg/ml (SD=63.01) and 81.90 ng/ml (SD=17.96), respectively; mean plasma cortisol concentrations for the patients and volunteers were 78.26 pg/ml (SD=66.44) and 67.02 ng/ml (SD=27.12), respectively. No group, time, or interaction effects for either plasma ACTH (F=1.41, df=1, n.s.) or cortisol (F=0.94, df=1, n.s.) were found, nor were the group mean 24-hour urinary free cortisol excretions significantly different (χ2=0.013, df=1, n.s.).

There was a trend for a correlation between CSF and plasma cortisol concentrations for all experimental subjects taken together (r=0.50, N=15, p<0.10). (Information on cortisol concentrations was missing for one volunteer in the correlation analysis.) The mean CSF-to-plasma cortisol ratios were 4.45% (SD=1.47%) (all subjects), 4.46% (SD=1.19%) (patients with PTSD), and 4.44% (SD=1.84%) (healthy volunteers), with no significant group differences. However, the CSF-to-urinary free cortisol ratio tended to be higher in the PTSD group (mean=3.94%, SD=2.38%, for all participants; mean=4.61%, SD=3.02%, for patients with PTSD; and mean=3.36%, SD=1.65%, for volunteers) (F=3.99, df=1, 11, p<0.08).

Neither plasma cortisol nor ACTH mean concentrations showed any significant relation to CSF CRH levels. However, mean CSF cortisol concentrations were significantly correlated with CSF CRH for all subjects (r=0.624, N=16, p<0.05) and showed similar, but nonsignificant, correlations within the PTSD group (r=0.47, N=8, n.s.) and the volunteer group (r=0.54, N=8, n.s.) (

Figure 1).

Discussion

Higher basal CSF cortisol concentrations were observed in veterans with chronic PTSD than in healthy subjects, despite normal plasma cortisol and 24-hour urinary free cortisol concentrations. The higher CSF cortisol concentrations were uniformly attributable to higher CSF cortisol nadirs in the PTSD subjects over the 6-hour collection period; CSF cortisol zeniths were similar across study groups. Accordingly, intraindividual variability in the CSF cortisol concentration was diminished in the men with chronic PTSD relative to healthy volunteers.

The significant positive correlation observed between mean CSF CRH and CSF cortisol levels may reflect a bidirectional regulation of glucocorticoids and CRH.

Although the ratio of CSF to plasma cortisol was nearly identical in both groups, the ratio of CSF cortisol to urinary free cortisol was higher in the PTSD group than the healthy group. Cortisol, unbound in urine, is mostly free (<10% bound) in CSF and largely protein-bound (>90%) in plasma (4, 10). Studies show that the blood-CSF steroid interchange is complex; CSF glucocorticoid levels respond to increases in peripheral cortisol, but other, as yet poorly understood, factors independently modulate CNS cortisol levels

(5,

7,

11,

12). Multidrug-resistant P-glycoprotein regulates CNS cortisol access

(6). Preclinical studies demonstrating the CNS presence of precursors and enzymes for cortisol synthesis raise the possibility of de novo brain synthesis in humans

(13). Therefore, the elevated ratio of CSF to urinary free cortisol excretion in the PTSD group could be attributable to 1) an increase in unbound cortisol available for transport or differences in rate of transport into the CNS, 2) a decrease in CSF cortisol clearance or metabolism, 3) increased de novo cortisol synthesis in the CNS, or 4) diminished tissue uptake of CSF cortisol by the brain.